DAYAK LIFE

The Dayaks have traditionally lived in the forests in both the Malaysian and Indonesian sides of Borneo. They are distinguished from the Malay population in that for the most part they are not Muslims and distinguished from the Penan in that have traditionally been settled while the Penan were nomadic. Historically, many Dayak communities lived in large communal longhouses, had no rigid class hierarchy, and relied on shifting cultivation as their primary means of subsistence.

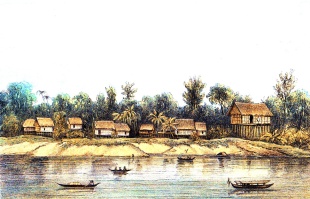

Dayaks have traditionally lived in villages with multifamily dwelling, often including longhouses (See long houses above and under the Iban). To get around, Dayaks have traditionally navigated the rivers of Borneo with dugout canoes that were propelled forward by ten standing punters. No they mostly use motorized dugouts or long boats.

Although they reside in longhouses that traditionally served as a means of protection against slave raiding and intervillage conflict, the Dayak are not communalistic. They have bilateral kinship, and the basic unit of ownership and social organization is the nuclear family. The various Dayak peoples have typically made a living through swidden agriculture.

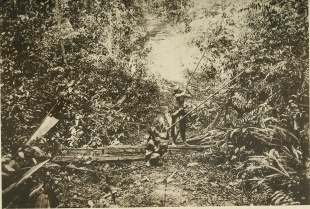

In spite of leeches, snakes and insects, Dayaks often go barefoot in the rain forest because they say it gives them surer footing. They also go naked except for shorts. Their advise with leeches is to "surrender what they want to them. If they feel happy, you will too." Dayak porters are capable of carrying loads three times their body weight in rattan basket that are secured to their heads and backs. When walking through the forest, Dayaks carry machetes known as manduas to clear a path. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

Cleanliness has traditionally been very important to th Dayaks. Harrison W. Smith wrote in National Geographic in 1919: “As with most of the Sarawak tribes, personal cleanliness is the rule. The Dayaks have been known to comment on a white traveler to the effect that, although he seemed to be otherwise alright, he did not bathe as frequently as they considered necessary.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

SABAH: ORANGUTANS, GREAT DIVING AND ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Dayak Society

Political unity is rarely advanced beyond the village level. There is little social stratification although slavery was, and may still be, practiced. The Dayaks follow “adat”, or customary laws. Their way of life depends on reciprocal social networks for planting, harvesting and assistance in times of trouble. “Potong pontan” is a welcoming ceremony in which guest are given a machete by the village chief and asked to cut through plants placed at the entrance of the village to purge evil spirits. As they hack away the guests explain why they are visiting.

Dayaks have traditionally lived in villages along Borneo’s complex river system, grown rice and other crops in shifting slash-and-burn plots, tended orchards and gardens that look like forests to outsiders, tapped rubber trees, and gathered forest products such as rattan, resins and gums. Dayaks grow special kinds of rice, sometimes named after ancestors, adapted for their home territory.

Traditional Dayak society was historically stratified into three social classes: nobles, common people and slaves. Nobles tend live in the upriver sections of villages, were individuals of wealth and influence, with status derived largely from their ownership of prestige items such as gongs and porcelain. Village chieftains were drawn from this group. Slaves consisted of individuals who accepted servitude to repay debts, and captives taken in war and sometimes designated for human sacrifice. Although slavery was formally abolished in 1892, the social stigma associated with slave ancestry has persisted. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Ma’anyan Dayak tribe retain their traditional beliefs about the spirit world and society and continue to practice old agricultural rituals and complex mortality ceremonies and employ shaman as healers. Their cemeteries indicate social hierarchy. The cemetery of the nobility is located in the most upstream position of the river, followed by warriors. Ordinary folk are buried further downstream, slaves further still.

Dayak Family and Sexuality

The basic kinship unit for many Dayak groups consists of a nuclear family extended to include the families of married daughters, with descent and kinship traced through both the mother’s and father’s lines. Customarily, the ideal marriage is between the grandchildren of two brothers. Also favored are unions between the children of two sisters or between the children of a brother and a sister. By contrast, marriages between the children of brothers, and especially those crossing generations, such as between an uncle and a niece, are strictly forbidden. In cases of such violations, the offending couple is required to eat from a pig’s feeding trough before the entire village; otherwise, both the couple and the community are believed to face supernatural misfortune. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Polygamy is rare, largely because taking a second wife is considered too costly. Divorce, however, is relatively common; in one Ma’anyan village, as many as one in four marriages reportedly ended in divorce. The most frequent cause is infidelity by either spouse. Barrenness alone is not considered sufficient grounds for divorce, as childless couples may adopt children. When divorce occurs, younger children usually remain with the mother, while older children may be taken in by relatives from either side, depending on the circumstances.

The Dayaks have long been characterized, often with exaggeration by Western observers, as having relatively permissive sexual norms. Within Ngaju society, women’s sexual satisfaction was accorded significant importance, as reflected historically in practices such as the wearing of the penis pin, or palang, known among the Ngaju primarily in the Katingan Valley. Young men and women are permitted to interact freely, including joking and dancing, when elders are present. A man may converse with another man’s wife provided a third person is present. However, if a man is discovered alone in an isolated place with a woman who is neither his wife nor his sister, he is required to pay a fine known as singér.

Dayak Marriage

Men typically marry at about age 20, while women marry around age 18. In the past, marriages were arranged by parents, but today, especially among school-educated youth, individuals generally choose their own spouses. To initiate a marriage proposal, the man’s parents present a sum of money to the woman’s parents on his behalf.

The woman’s parents then convene their kin to consider the proposal, assessing the prospective groom’s character and ensuring that he is not descended from slaves. If the proposal is rejected, the money is returned. If accepted, the woman’s family arranges the betrothal ceremony and feast, covering all associated costs.

Subsequently, the two families negotiate the bride-price, known as palaku, along with the wedding expenses to be borne by the man’s family, and set a wedding date. The woman’s family may demand a high palaku to assert its social standing, although an excessive amount may prompt the man’s family to withdraw the proposal. Before the wedding, the man’s side presents bahalai, cloth for a woman’s sarong, material for a kebaya blouse, perfume, gold rings, and other gifts. The palaku is often later returned to the husband if he proves himself to be a devoted and responsible spouse. In addition, the groom presents saput, typically an heirloom gong or porcelain, to his wife’s siblings as a gesture of gratitude for their care of her. A similar gift, panangkalau, is given to any older unmarried sister of the bride to avert misfortune associated with a younger sister marrying first. The marriage contract, known as surat pisek, is sealed through the ritual ingestion of medicinal herbs. Depending on the financial capacity of the man’s family, the interval between betrothal and wedding may range from one month to as long as three years.

Dayak Houses and Villages

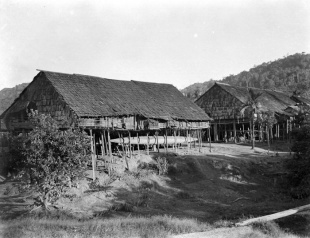

Dayak houses in the interior of Kalimantan are generally of two types: square, single-family houses and rectangular communal longhouses. The square, single-family Dayak house is much smaller and more precisely constructed, housing only one family. Although simple in form, such homes are often distinguished by refined symbolic details on the exterior. Particularly notable are the finely carved wooden finials extending from the ends of the roof, which accentuate the upper tier of the structure. These houses are commonly arranged around a central open pavilion that serves as a communal gathering space. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

When travelling up the Kapuas River in Central Kalimantan, you will pass typical Dayak longhouses, with smoke wafting from atop roofs disappearing behind leafy ferns and rows of coconut trees. Inside, mothers will have just extracted the coconut juice to prepare a big dinner that smells most inviting. A Dayak longhouse consists of more than 50 rooms with many kitchens, making it one of the largest houses built. Although many may look delapidated, nonetheless, they are very sturdy, most built decades ago, and are made of strong ironwood. But today such longhouses are fast disappearing or falling into disuse as people prefer to live in smaller homes rather in one large communal dwelling. [Source: Indonesia Tourism website]

The river is necessary for the community for the supply of water and food, and of course as a means for travel, and communications with the outside world. Village also house an impressive number of the bone houses or sandungs, used to store the ancestors’ bones. Decorated by extravagant carvings, totem poles and painted brightly, these sandungs are reminders of the ancient Dayak heritage.

Dayak Longhouse

The well-known Dayak longhouses — known as uma dadoq, betang and lamin — consist of a series of enclosed family apartments called amin, allowing entire villages to live together under a single roof. The headman’s residence is located at the center of the structure, distinguished by a higher ceiling than the surrounding sections. Families treat the rear of their amin as a sacred space for storing heirlooms, and many also prepare food within their own apartments. Longhouses serve not only as residences but also as important venues for ritual performances.[Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Longhouses are generally windowless buildings and often grow gradually over time, with new sections added as needed. Because additions may use different materials or rest on piers of varying heights, longhouses can take on an irregular, rambling appearance. A long verandah runs the entire length of the structure, functioning as a shared public space where inhabitants, sometimes numbering in the hundreds, gather to socialize and receive visitors. Dayak settlements are typically located along rivers, with village boats moored below the houses.

Dayak longhouses are large communal dwellings, where an entire community of extended families resides. These longhouses are normally located along river banks and are built on strong posts raised above the seasonal flooding. Such longhouses, therefore, are usually built on 5 meters and sometimes even 8 meter posts, while entry to the house is by a tangka or ladder, notched into a huge log. As the ladder is pretty precarious, visitors must be careful when climbing.

Dayak Food

Dayaks have traditionally followed the fruiting patterns of the trees which usually has corresponded with the migratory patterns of the animals they hunted. Bamboo shoots that taste like cabbage are harvested from dark freshwater pools of water and boiled for consumption. Sago is taken from palm trees. Tribes in the forest have experimented with dryland rice introduced by missionaries. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

They Dayaks traditionally grew rice. During the planting season men made holes with bamboo sticks and the women put the seeds in the holes. They also raised pigs and grew vegetables, tobacco, sugar cane and bananas. They liked to drink sweet tea and offered it as a special treat to guests.

Dayaks extract products such as honey and rattan from the forest to sell. Tubers and fruits are gathered for food. Herbs, leaves and roots are collected for medical uses. Sometimes they left small plots of the rain forest untouched so they had food sources in times of drought. In Borneo, a plate of food that look like spaghetti is sometimes parasitic fish worms.

Dayak Hunting

Monkeys and flying squirrels were traditionally dispatched by Dayak hunters with blowguns with poison darts and wild pigs, deer, pythons and bear were hunted with spears. Eggs laboriously collected from wild jungle fowl were usually reserved for children. Other traditional Dayak weapons include axes, machetes and knives. Fishing techniques range from using fishing rods to using their unique-style seine. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

When hunting deer and or wild boar, Dayak tribesmen generally do not actively pursue animals but rather like to hunt in clearings drawing the animals to them. They have a unique method for attracting deer: they imitate the sound of a young deer. Since does (female deer) always protect their young, if the call is done well enough the female deer will approach as soon as they hear the sound for help. In hunting, Dayak have traditionally used lances or blowpipes. A blowpipe is very is long and can be fitted with a kind of bayonet so it also functions as a lance. Blowpipe darts used for hunting are smeared with a poisonous concoction that paralyzes or even kill prey. Blowguns are especially good for hunting monkeys and other animals in the trees.

Dayak blowguns are two to three meters long and hollowed out of a single piece of hardwood that curves slightly upwards to compensate for the propensity of the dart to drop. They have bore spirals like those in a rifle that help the dart travel straight and true. The Kenyans reputedly make the best blowguns and the Penans are the best at using them for hunting. The end is sometimes sharpened, and since it is one piece of hollowed out wood the blowgun can can also be used as a spear. Blowguns can be accurate up to 75 meters. ♢

The darts are tipped with as many as five different kinds of hand-mixed poisons. Nerve poisons are favored. Different poison are used for different species. With monkeys the trick is getting the dose right, two hunters told Blair. If the dose is too strong the monkey dies clinging to the tree tops. If it is just right "it tumbles down and gives you your dart back." The monkeys are roasted over an open fire and the area that has been poisoned is removed. If they are fried or boiled the poison spreads. Large monitor lizards are the most common prey and endangered gibbons, which sell for as much as $5000 on the black market, are also killed. ♢

Dayak Feast in the 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: ““3rd — Took leave of this pleasant valley, and by another and shorter road than we came reached Ka-at. We arrived in good time on the hill, and found every thing prepared for a feast. There was nothing new in this feast. A fowl was killed with the usual ceremony; afterwards a hog. The hog is paid for by the company at a price commensurate with its size: a split bamboo is passed round the largest part of the body, and knots tied on it at given distances; and according to the number of these knots are the number of pasus of padi for the price. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“Our host of Nawang, Niarak, arrived to this feast with a plentiful supply of toddy; and before the dance commenced, we were requested to take our seats. The circumstances of the tribe, and the ability of Nimok, rendered this ceremony interesting to me. The Sow tribe has long been split into four parties, residing at different places. Gunong Sow, the original locality, was attacked by the Sakarran Dyaks, and thence Nimok and his party retired to Ra-at. A second smaller party subsequently located at or near Bow, as being preferable; whilst the older divisions of Jaguen and Ahuss lived at the places so named. Nimok's great desire was to gather together his scattered tribe, and to become de facto its head. My presence and the Datus* was a good opportunity for gathering the tribe; and Nimok hoped to give them the impression that we countenanced his proposition. The dances over, Nimok pronounced an oration: he dwelt on the advantages of union; how desirous he was to benefit his tribe; how constantly it was his custom to visit Sarawak in order to watch over the interests of the tribe — the trouble was his, the advantage theirs; but how, without union, could they hope to gain any advantage — whether the return of their remaining captive women, or any other ? He proposed this union; and that, after the padi was ripe, they should all live at Ba-at, where, as a body, they were always ready to obey the commands of the Tuan Besar or the Datu.-

“This was the substance of Nimok's speech. But the effect of his oratory was not great; for the Bow, and other portions of the tribe, heard qoldly his proposition, though they only opposed it in a few words. It was evident they had no orator at all a match for Nimok: a few words from Niana drew forth a second oration. He glanced at their former state; he spoke with animation of their enemies, and dwelt on their great misfortune at Sow; he attacked the Sing& as the cause of these misfortunes: and spoke long and eloquently of things past, of things present, and things to come. He was seated the whole time; his voice varied with his subject, and was sweet and expressive; his action was always moderate, principally laying down the law with his finger on the mats. Niarak, our Sing friend, attempted a defence of his tribe; but he had drunk freely of his own arrack; and his speech was received with much laughter, in which he joined. At this juncture I retired, after saying a few words; but the talk was kept up for several hours after, amid feasting and drinking.-

Attending a Festival of Head-Hunting Dyaks in the 1840s

Henry Keppel wrote in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy” in th early 1840s: We ascended the river in eight or ten boats. The scene to us was most novel, and particularly fresh and beautiful. We stopped at an empty house on a cleared spot on the left bank during the ebb-tide, to cook our dinner; in the cool of the afternoon we proceeded with the flood; and late in the evening brought up for the night in a snug little creek close to tjie Chinese settlement. We slept in native boats, which were nicely and comfortably fitted for the purpose. At an early hour Mr. Brooke was waited on by the chief of the Kunsi; and on visiting their settlement he was received with a salute of three guns. We found it kept in their usual neat and clean order, particularly their extensive vegetable-gardens; but being rather pressed for time, we did not visit the mines, but proceeded "to the villages of different tribes of Dyaks living on the Sarambo mountain, numbers of whom had been down to welcome us, very gorgeously dressed in feathers and scarlet. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“The foot of the mountain was about four miles from the landing-place; and a number of these kind savages voluntarily shouldered our provisions, beds, bags, and baggage, and we proceeded on our march. We did not expect to find quite a turnpike-road; but, at the same time, I, for one, was not prepared for the dance led us by our wild catlike guides through thick jungle, and alternately over rocky hills, or up to our middles in the soft marshes we had to cross. Our only means of doing so was by feeling on the surface of the mud (it being covered in most places about a foot deep with grass or discoloured water) for light spars thrown along lengthways and quite unconnected, whilst our only support was an occasional stake at irregular distances, at which we used to rest, as the spars invariably sank into the mud if we attempted to stop; and there being a long string of us, many a fall and flounder in the mud (gun and all) was the consequence.-

“The ascent of the hill, although as steep as the side of a house, was strikingly beautiful. Our resting-places, unluckily, were but few; but when we did reach one, the cool fresh breeze, and the increasing extent and variety of scene; — our view embracing, as it did, all the varieties of river, mountain, wood, and sea, — amply repaid us for the exertion of the lower walk; and, on either hand, we were sure to have a pure cool rivulet tumbling over the rocks. While going up, however, our whole care and attention were requisite to secure our own safety; for it is not only one continued climb up ladders, but such ladders I They are made of the single trunk of a tree in its rough and rounded state, with notches, not cut at the reasonable distance apart of the rattlins of our rigging, but requiring the knee to be brought up to the level of the chin before the feet are sufficiently parted to reach from one step to another; and that, when the muscles of the thigh begin to ache, and the wind is pumped out of the body, is distressing work.-

“We mounted, in this manner, some 500 feet; and it was up this steep that Mr. Brooke had ascended only a few months before, with two hundred followers, to attack the Singe Dyaks. He has already described the circular halls of these Dyaks, in one of which we were received, hung round, as the interior of it is, with hundreds of human heads, most of them dried with the skin and hair on; and to give them, if possible, a more ghastly appearance, small shells (the cowry) are inserted where the eyes once were, and tufts of dried grass protrude from the ears. But my eye soon grew accustomed to the sight; and by the time dinner was ready (I think I may say we) thought no more about them than if they had been as many cocoa-nuts.-

“Of course the natives crowded round us; and I noticed that with these simple people it was much the same as with the more civilised, and that curiosity was strongest in the gentler sex; and again, that the young men came in more gorgeously dressed — wearing feathers, necklaces, armlets, ear-rings, bracelets, besides jackets of various-coloured silks, and other vanities — than the older and wiser chiefs, who encumbered themselves with no more dress than what decency actually required, and were, moreover, treated with the greatest respect. We strolled about from house to house without causing the slightest alarm: in all we were welcomed, and invited to squat ourselves on their mats with the family. The women, who were some of them very good-looking, did not run from us as the plain-headed Malays would have done; but laughed and chatted to us by signs, in all the consciousness of innocence and virtue.-

“We were fortunate in visiting these Dyaks during one of their grand festivals (called Maugut); and in the evening, dancing, singing, and drinking were going on in various parts of the village. In one house there was a grand fete, in which the women danced with the men. The dress of the women was simple and, curious — a light jacket open in front, and a short petticoat not coming below the knees, fitting close, was hung round with jingling bits of brass, which kept “making music'* wherever they went. The movement was like all other native dances — graceful, but monotonous. There were four men, two of them bearing human skulls, and two the fresh heads of pigs; the women bore wax-lights, or yellow rice on brass dishes. They danced in line, moving backwards and forwards, and carrying the heads and dishes in both hands; the graceful part was the manner in which they half turned the body to the right and left, looking over their shoulders and holding the heads in the opposite direction, as if they were in momentary expectation of some one coming up behind to snatch the nasty relic from them. At times the women knelt down in a group, with the men leaning over them. After all, the music was not the only thing wanting to make one imagine oneself at the opera. The necklaces of the women were chiefly of teeth — bears' the most common — human the most prized. In an interior house at one end were collected the relics of the tribe. These consisted of several round-looking stones, two deer's heads, and other inferior trumpery. The stones turn black if the tribe is to be beaten in war, and red if to be victorious: any one touching them would be sure to die; if lost, the tribe would be ruined.-

“The account of the deer's heads is still more curious: A young Dyak having dreamed the previous night that he should become a great warrior, observed two deer swimming across the river, and killed them; a storm came on with thunder and lightning, and darkness came over the face of the earth; he died immediately, but came to life again, and became a rumah guna (literally a useful house) and chief of his tribe; the two deer still live, and remain to watch over the affairs of the tribe. These heads have descended from their ancestors from the time when they first became a tribe and inhabited the mountain. Food is always kept placed before them, and renewed from time to time. While in the circular building, which our party named "the scullery, “a young chief (Meta) seemed to take great pride in answering our interrogatories respecting different skulls which we took down from their hooks: two belonged to chiefs of a tribe who had made a resolute defence; and judging from the incisions on the heads, each of which must have been mortal, it must have been a desperate affair. Among other trophies was half a head, the skull separated from across between the eyes, in the same manner that you would divide that of a hare or rabbit to get at the brain — this was their division of the head of an old woman, which was taken when another (a friendly) tribe was present, who likewise claimed their half. I afterwards saw these tribes share a head. But the skulls, the account of which our informant appeared to dwell on with the greatest delight, were those which were taken while the owners were asleep — cunning with them heing the perfection of warfare. We slept in their “scullery;" and my servant Ashford, who happened to he a sleep-walker, that night jumped out of the window, and unluckily on the steep side; and had not the ground heen well turned up by the numerous pigs, and softened by rain, he must have been hurt.-

Dayak Art and Culture

Visitors to Dayak villages are often entertained with Dayak traditional dances and music made with plucked stringed instruments and drums. The Ngaju Dayak, the dominant tribe along the Kahayan and Kapuas Rivers, are known for their arts, especially their wooden-coffins at elevated cemeteries, ships of the dead and funeral poles. Upriver Dayak villages contain many funeral poles. The best examples of funerary art in Kalimantan are found on the upper reaches of the Kahayan River at Tumbang Kuring.

Dayaks are renowned for their rattan weaving skill. Intricately decorated baby carriers are adorned with ancient beads, coins, crocodile teeth, bear claws, dog teeth and magical amulets that keep the baby safe from evil spirits. The human oils deposited by constant use helps them resist rot. [Source: "Ring of Fire" by Lawrence and Lorne Blair, Bantam Books, New York, ♢]

Dayaks produce magical dog and serpent carvings. Ironwood is used for the foundations of houses and for carving. The Ngaju and Dusun Dayak people produce giant “temadu” (carved ancestor totems depicting the dead).

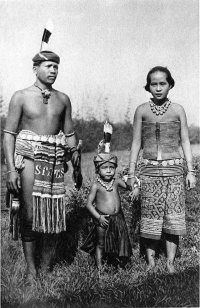

Dayak Clothes, Tattoos, Earrings and Ornaments

Dayak men traditionally wore loincloths and had elaborate tattoos running up their shoulders. Sometimes they covered much of their body with tattoos. Women wore knee-length sarongs and went topless.

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy” in the 1840s: “The dress of the men consists of a piece of cloth about -fifteen feet long, passed between the legs and fastened round the loins, with the ends hanging before and behind; the head-dress is composed of bark-cloth, dyed bright yellow, and stuck up in front so as to resemble a tuft of feathers. The arms and legs are often ornamented with rings of silver, brass, or shell; and necklaces are worn, made of human teeth, or those of bears or dogs, or of white, beads, in such numerous Strings as to conceal the throat. A sword on one side, a knife and small betel-basket on the other, complete the ordinary equipment of the males; but when they travel they carry a basket slung from the forehead, on which is a palm mat, to protect the owner and his property from the weather. The women wear a short and scanty petticoat, reaching from the loins to the knees, and a pair of black bamboo stays, which are never removed except the wearer be enceinte. They have rings of brass or red bamboo about the loins, and sometimes ornaments on the arms; the hair is worn long; the ears of both sexes are pierced, and ear-rings of brass inserted occasionally; the teeth of the young people are sometimes filed to a point and discoloured, as they say that "Dogs have white teeth." They frequently dye their feet and hands of a bright red or yellow colour; and the young people, like those of other countries, affect a degree of finery and foppishness; whilst the elders invariably lay aside all ornaments, as unfit for a wise person or one- advanced in years.” [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

Men and women, boy and girls all used to sometimes wear clusters of brass earrings that pulled their ears and made gaping holes in their ear lobes, pulling them down to their shoulders. Some Dayak women used to stretch their earlobes with rings, put tattoos on their hands and put gold on all their teeth. The practice is still done in some remote areas. Trimmed earlobes is a sign of conversion to Christianity.

In the old days most Dayak men wore tattoos to commemorate headhunting expeditions and women tattooed their forearms and calves with bird and spirit designs. Few young women receive tattoos except some who live deep in the interior. In the past men were expected to earn their tattoos by taking heads. Markings and tattoos today sometimes represent “a modern interpretation of traditional headhunting tattoos.” A Dayak elder told photographer Chris Ranier, “When we have lost our tattoos we have lost our culture.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026