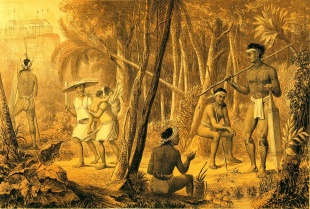

NGAJU DAYAKS

The Ngaju Dayaks of Central Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo are the largest Dayak group in terms of population and the most influential politically and culturally in Indonesia. The name "Ngaju" signifies upriver (as opposed to ngawa, downriver). The Ngaju distinguish themselves from the Ot Danum, related but more conservative peoples living even further upriver (Ot itself means "upriver" and Danum means "water" or "river"). [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Ngaju Dayaks (pronunced NGA-joo DAH-yahk) originated from a homeland along the Kahayan River in present-day Central Kalimantan province and spread as far west as the Seruyan Valley. entral Kalimantan province consists of several north-south running river valleys from the Schwaner and Muller Mountains to the Java Sea. Swamps extend deep into the interior from the coast, where they give way to dense jungle. Ngaju Dayaks settled at the mouth of the Kapuas River, but as one approaches the sea, they become increasingly mixed with non-Dayak peoples. The upper reaches of the rivers are largely inhabited by the related Ot Danum Dayak.

According to the Christian group Joshua Project, the Ngaju Dayak population in the early 2020s was 1,205,000.According to the 2000 census in Indonesia, when they were first listed as a separate ethnic group, the Ngaju constituted 18 percent of Central Kalimantan's population, or 334,000 out of 1.86 million. They were outnumbered by the Banjarese who made up 24 percent of the population and equaled the 18 percent of the Javanese. . A 2003 estimate put the number of Ngaju speakers at 800,000. ^^

Ngaju Language belongs to a group of closely related Austronesian languages called the Barito family. It is spoken from the Schwaner Mountains and the upper Mahakam valley to the southeast corner of Borneo, excluding the territory of the people who speak the language called Banjarese. TFor the last five generations, the Ngaju people have had a system of given and family names (the Ot Danum people adopted this system only very recently). A man's full name consists of his given name, his father's name, and the name of a patrilineal ancestor. Upon marriage, a woman keeps her given name but replaces the rest with her husband's full name. For example, a woman named Luise H. Tuwe who marries Alex Banda Mambay becomes Luise A. B. Mambay. ^^

RELATED ARTICLES:

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

SABAH: ORANGUTANS, GREAT DIVING AND ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

History of the Ngaju Dayaks

Beginning in the 1830s, the Dutch colonial administration actively encouraged Protestant missionary activity among Dayak communities. This policy slowed the spread of Islam, strengthened a sense of distinct identity among interior peoples, and contributed to the emergence of a Christianized Ngaju elite. Following Indonesian independence, the Ngaju found themselves incorporated into the Banjarmasin-centered province of South Kalimantan. Both animist and Christian Ngaju feared political and social marginalization within a province dominated by the Muslim Banjarese majority. After engaging in a limited guerrilla struggle against the central government, the Ngaju succeeded in achieving the creation of their own province, Central Kalimantan, in 1957, along with official tolerance of their traditional religion. This success was due in large part to the high regard held by the national military for the Ngaju leader Tjilik Riwut, a former parachutist and hero of the Indonesian revolution. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Despite these political gains, the Ngaju have continued to face demographic pressures within their own province. During the New Order period from 1966 to 1998, government transmigration programs dramatically increased the number of settlers in Central Kalimantan, as in other parts of the island. Migrants from Java, Bali, Madura, and elsewhere rose from about 13,000 between 1971 and 1980 to around 180,000 between 1981 and 1990, with similar numbers arriving in the following decade. At the same time, aggressive state-led development policies promoted extensive logging, reducing forest cover in Central Kalimantan from 84 percent of the total area in 1970 to 56 percent by 1999. This environmental degradation severely reduced the land available for Ngaju swidden agriculture.

Political uncertainty in the late 1990s further heightened tensions. In 1996 and 1997, as President Suharto appeared to be preparing to step down and a succession struggle loomed, violence broke out in neighboring West Kalimantan, where Dayak groups targeted Madurese transmigrants. Initially triggered by an incident between Malays and Madurese, clashes resumed in 1999 after Suharto’s fall amid the Asian financial crisis. In West Kalimantan, the conflict resulted in 186 deaths and the displacement of at least 26,000 Madurese. In Central Kalimantan, violence erupted in 2001, spreading from the town of Sampit, which had become majority Madurese, to the provincial capital of Palangkaraya, 220 kilometers away. Between February and May, nearly 500 Madurese were killed, and almost the entire Madurese population of more than 100,000 fled the province. These attacks reflected not only long-standing grievances against the Madurese but also broader resentments over the hardships experienced by Dayaks during the New Order period. Other groups, including Malays, Bugis, and even Chinese, were reported to have participated in the violence. Although Central Kalimantan has remained relatively calm since then, tensions between the interests of Borneo’s indigenous peoples and the objectives of the national government continue to persist.

Ngaju Dayak Religion

According to the Christian group Joshua Project, 80 percent of Ngaju Dayak are Christians and 5 10 to 50 percent are Evangelicals.According to the 1980 census, 17.71 percent of the population of Central Kalimantan, and a much higher proportion of the Ngaju in particular, adhered to traditional animist beliefs, especially in upriver villages. About 14.27 percent of the provincial population identified as Protestant, while 1.94 percent was Catholic. Because formal schooling in the region was initially introduced by missionaries, the Ngaju elite is predominantly Christian. The remainder of the population of Central Kalimantan is Muslim. In the past, conversion to Islam often entailed abandoning a Dayak identity in favor of a Banjarese or Malay one. More recently, however, many Dayaks, including the Bakumpai, a subgroup of the Ngaju, have embraced Islam while retaining their Dayak language and cultural identity.[Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditional Ngaju religion centers on the belief in ganan, spirits believed to inhabit house posts, large rocks or trees, dense forests, and bodies of water. These spirits are classified into sangiang or nayu-nayu, regarded as benevolent; taloh or kambin, considered malevolent; and liau, the spirits of ancestors. The pantheon includes supreme deities associated with the upper world, male, and the underworld, female. Religious practice ranges from small offerings to ancestors to elaborate ceremonies marking major life transitions and communal rituals intended to ensure good harvests or combat epidemics.Balian, or priestesses, and basir, transvestite priests, enter states of spirit possession and speak an esoteric ritual language. The afterlife is imagined as closely resembling the world of the living, with settlements of houses lining a riverbank, although in earlier times the most honored dead, whose descendants could afford human sacrifices, were believed to inhabit elevated hilltop estates.

The Indonesian state’s requirement that all citizens adhere to a monotheistic religion has posed a challenge to the continued practice of traditional Ngaju animism. In response, Ngaju leaders formalized their beliefs under the name Kaharingan, a term adopted by Tjilik Riwut from Danum Kaharingan Belum, A sixteen-member council, composed almost entirely of Ngaju, oversees theology and ritual practice, although it does not include balian or basir.

Ngaju Dayak Funerals

Funeral rites for Ngaju Dayaks are conducted in two stages. The initial burial ceremony sends the soul of the deceased to the lower level of heaven, while the secondary rite, known as tiwah, allows the soul to ascend to the highest heaven, Lewu Tatau. There, it is believed to meet the supreme deity Ranying and to be forever free from disaster, hardship, and fatigue. In the first stage, the body is placed in a wooden coffin shaped like a boat or a rice-pounding trough. Masked dancers perform to repel malevolent spirits, while priests chant to the rhythm of drums. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

A tiwah ceremony is extremely costly, typically requiring the equivalent of US$6,000 to US$12,000 in the late 2000s, a lot of money for most Dayak families. It involves the sacrifice of numerous water buffalo and pigs and the feeding of large numbers of guests from villages across a wide region. Because of these expenses, families usually organize a tiwah only once every seven years or so, and those who die in the intervening period are honored together in a communal ceremony lasting from one to three weeks. During this time, balian chant legends and genealogies from memory for hours at a stretch and perform ritual dances. The large gatherings also create opportunities for trade and entertainment, with stalls selling prepared food and other goods and gambling taking place nearby.

During the tiwah, the bones of the deceased are exhumed from the raung; in some cases, the remains must first be cremated. The bones are then placed in sandung, small mausoleum-like structures about 2 meters high, elaborately carved with images of the hornbill, symbolizing the upper world, and the naga serpent, representing the lower world. Among the Ma’anyan, the remains of entire families may be interred together in larger mausolea known as pambak. While traditional sandung were made of wood, modern examples are often constructed from concrete. Sacrificial animals are slaughtered while bound to a sepunduq, a carved post depicting fearsome demons with fangs, protruding tongues, and elongated noses. Another important form of funerary art is the sengkaran, a 6-meter pole representing the tree of life and the structure of the cosmos. At its summit is a hornbill flying above a forest of spears embedded in the back of a naga resting on a Chinese heirloom jar. Also significant are the “ships of the dead,” small model sailing vessels crewed by benevolent spirits fashioned from gutta-percha; today, such models are produced throughout Kalimantan, often for sale to tourists.

Ngaju Dayak Society

Traditional Ngaju society was historically stratified into three social classes: the utus gantong or utus tatau, the utus rendah, and slaves. The utus gantong, who lived in the upriver sections of villages, were individuals of wealth and influence, with status derived largely from their ownership of prestige items such as gongs and porcelain. Village chieftains, or demang, were drawn from this group. Slaves consisted of jipen, individuals who accepted servitude to repay debts, and rewar, captives taken in war and sometimes designated for human sacrifice. Although slavery was formally abolished in 1892, the social stigma associated with slave ancestry has persisted. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The utus rendah, who generally resided downriver, were free people but lacked comparable status and material prestige. Religious specialists, including balian and basir, could emerge from this class. These specialists, who were responsible for duties such as chanting at funerals, did not engage in agricultural labor, and offenses committed against them were punished more severely.

Prominent individuals traditionally adopted noble titles of Banjarese origin. Under the present Indonesian administrative system, demang, appointed for life on the basis of personal qualities, serve as intermediaries between village heads (kepala desa) and district heads (camat). The kepala desa is elected for life and is assisted by a secretary (sekretaris) and an official responsible for agriculture and land matters (kepala padang). A council of elders advises the village head, although all community members have the right to voice opinions on matters of shared concern, with particular attention given to those who have experience beyond the village. Many villages, especially those located far upriver, function in practice with a high degree of autonomy from higher levels of administration. Unwritten customary law emphasizes fines and ritual acts to appease offended spirits, with the village council, chaired by the village head, determining appropriate sanctions.

Ngaju Dayak Villages and Houses

Traditionally, Ngaju Dayak villages were generally located on or near rivers, which were historically the only means of travel between settlements. These villages included a central community house and a place to dock boats. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Most people spend up to half of the year away from the main settlement, living instead in smaller hamlets near their swidden, or shifting-cultivation, fields, and return to the primary village only for major ritual celebrations. Houses are typically constructed either directly along the riverbank or along roads running parallel to the river. Longhouses, known as betang, are now found mainly among the Ot Danum, although among some other Dayak groups a single longhouse may contain the equivalent of an entire village, with as many as 50 separate family rooms, or bilik. Among the Ngaju, longhouses were built only by a small number of individuals who had accumulated sufficient wealth to finance their construction. Because these structures represented an enormous investment, they were not abandoned even when owners were compelled to cultivate swidden fields located at increasing distances.

Today, Ngaju families generally live in large extended-family houses, known as umah hai, which accommodate between one and five nuclear families, consisting of a couple, their unmarried children, and their married daughters with their families. These houses are raised on pillars approximately 2.5 meters high and have walls made of wooden shingles or bark. More affluent families may build houses in a “Dutch” style, furnished with chairs, coffee tables, china cabinets, and similar items, in contrast to traditional houses, which are typically unfurnished.

Ngaju Dayak Food and Clothes

The staple foods of Ngaju Dayaks includse rice, cassava, and a variety of tubers. Cassava leaves are commonly prepared as a side dish, as are river fish. Game is eaten only occasionally and may include wild pigs, monkeys, snakes, and wild fowl. Regional specialties include sayur rim-bang, a large eggplant cooked with river fish; sayur ambut, a strongly flavored dish combining fish with tender rattan shoots; and wadi and paksem, fermented mixtures of meat, such as fish, wild pig, deer, or deermouse, with rice. Durian is a favored sweet and is preserved as tempoyak or processed into dodol, a chewy taffy. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Anding, an alcoholic beverage made from glutinous rice, plays an important role in rituals and is an essential element of celebrations. Tea and coffee are consumed in everyday life. Another drink, barum gula, is prepared by fermenting about 4 kilograms of boiled glutinous rice with cloves, cinnamon, and peppers in a jar, then adding sugar after about a week. Both men and women commonly chew betel nut.

In the past, the Ngaju produced cloth from bark or wove textiles from cotton. Today, most people wear manufactured clothing brought in through coastal ports. Although less common than in earlier times, Ngaju, like other Dayak groups, have traditionally worn intricate tattoos and stretched their earlobes with multiple earrings, sometimes extending them down to the shoulders.

Traditional ceremonial attire for men includes a headcloth adorned with hornbill feathers, a sleeveless shirt, short trousers, and two cloth panels worn front and back reaching to the knees. This is complemented by a penyang, a belt made of leopard claws, bead necklaces, a mandau sword, and a richly carved wooden shield. Women’s ceremonial dress is similar, but the front and back cloths are decorated with gold thread and beads, the penyang is made of copper plates, and numerous bracelets are worn.

Ngaju Dayak Art, Culture and Dance

All Ngaju Dayak ceremonies are accompanied by the ije karepang, an ensemble of five Javanese gongs, often supplemented by additional instruments such as the tarai, a flat gong, the tangkanong, a xylophone, and gandang drums. Popular forms of recreation include cockfighting and kinyah, a style of martial art related to Malayan silat. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Each traditional dance has a specific purpose within ceremonial life. The deder ketingan provides young people with an opportunity to socialize during festive gatherings. The enggang terbang, or “flying hornbill,” honors the ancestors. The kanjan halu, originally a post-harvest thanksgiving dance to the gods, is now performed as entertainment during tiwah funeral feasts. The kinyah kambe is a trance or spirit-possession dance, while the balian bawo is performed for healing. The giring-giring dance welcomes guests, and the manambang pangkalima commemorates victory in battle.

Traditional Ngaju arts include mat and basket weaving, textile weaving, canoe making, particularly among the Ma’anyan, pottery, and tattooing. Especially notable is the craftsmanship involved in producing mandau swords and sumpitan blowguns, which are distinctive for being made from a single shaft of ironwood drilled through its length. In contrast, non-Dayak blowguns are typically fashioned from split wood or bamboo bound together. Woodcarving is also highly developed, with Dayak art characterized by repeated geometric forms such as spirals, reflecting influence from the Dong Son culture of ancient northern Vietnam, as well as dense yet harmonious arrangements of stylized motifs, especially fantastical animals, inspired in part by Chinese art of the late Zhou dynasty.

Ngaju Dayak Hampatong Woodcarvings

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The Ngadju and Ot Danum peoples of southeastern Borneo create a variety of wood images to honor the dead and protect the living. Known collectively as hampatong, Ngadju and Ot Danum wood sculpture portrays both human and animal subjects as well as fearsome supernatural creatures and varies in scale from diminutive charms that can be held in the palm of the hand to imposing wood figures depicting ancestors and supernatural beings. Large hampatong are of two basic types: tajahan, or images representing the dead, and pataho, or guardian figures set up in a special shrine within the village to protect the community. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In the past, tajahan were created to memorialize two categories of the dead : deceased members of the community and enemies whose heads had been taken in war. Each category was commemorated in a separate shrine, which stood outside the village, where an image was erected to honor each deceased individual. The large ceramic trade jar depicted in this tajahan image strongly suggests that the person represented was a high-ranking member of the local community rather than an enemy. Holes in the base suggest that the figure may have formed a corner post for the enclosure surrounding a funerary shrine.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains several hampatong. One is a carved male figure who represents a guardian spirit or recently deceased individual.k3 the museum: The figure is seated with the knees bent and the legs drawn towards the body in a posture typical of this genre of figural sculpture. The arms are flexed at the elbows and point downwards towards the knees, while the hands join at the fingers to rest on the chest. The facial features include highly stylized large circular eyes and an angular nose in high relief. The figure wears an elaborate headdress with a headband adorned with floral motifs and four foliate projections that extend above the head.

The headdress itself is crowned with a bulb-shaped form with trailing element which extends down the back of the figure and may represent long hair dressed in an elaborate ‘ponytail’ coiffure. The figure itself sits on a section of carved panels also adorned with floral motifs, completing what would have been the decorative finial of a tall, typically unadorned, post from which it has now been cut away. These figures were erected outdoors, frequently positioned at the entrance to a house in order to ward off malevolent spirits or illness, or placed along paths leading to houses and as a marker of village boundaries. Hampatong that portray protective beings often have a prominently protruding tongue such as this one, which may well be a reference to oratory or speech associated with the animation of their metaphysical aspect. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ngaju Dayak Ceremonial Jars

Dayak ceremonial jars are highly valued heirlooms used in various significant spiritual and life-cycle rituals, including harvest blessings, marriage payments, and elaborate funerary rites. The jars are primarily imported Chinese or Siamese stoneware, treasured for their age, origin, and perceived spiritual power.

Various kinds of jars were great valued by Ngaju Dayaks. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Prized by indigenous peoples throughout Borneo, massive jars, known in Ngadju as tempayan, were primarily of Chinese origin. Originally obtained in exchange for forest products such as rhinoceros horn, hornbill ivory, bezoar stones, resin, and other commodities, the jars reached even the most remote inland communities and became treasured heirlooms, passed down within families as important marks of wealth and status. Prominently displayed in the main room of the family dwelling, tempayan were used to store rice or drinking water and also for the fermentation of rice wine.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Jars also served as burial vessels for important individuals, and in some cases, actual examples were incorporated into the memorial sculpture erected at funerary shrines. In this sculpture the tempayan, possibly representing a specific heirloom jar owned by the family of the individual, serves as a seat for the deceased. Clad in an elaborate headdress and enthroned upon the valuable jar, the subject, who would have been well known to the local community but whose identity is now lost, was almost certainly a prominent and wealthy man. Like all tempayan, it would have been commissioned and erected by relatives of the deceased as part of the elaborate tiwah (funeral feast) rites held in his honor.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026