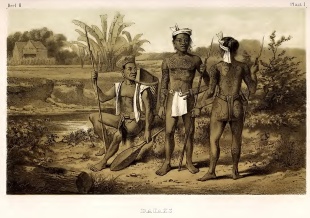

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “The Dyaks (or more properly Dayak) of Borneo offer to our view a primitive state of society; and their near resemblance to the Tarajahs of Celebes, to the inland people of Sumatra, and probably to the Arafuras of Papua, in customs, manners, and language, affords reason for the conclusion that these are the aboriginal race of the Eastern Archipelago, nearly stationary in their original condition. Whilst successive waves of civilisation have swept onward the rest of the inhabitants, whilst tribes as wild have arisen to power, flourished, and decayed, the Dyak in his native jungles still retains the feelings of earlier times, and shews the features of society as it existed before the influx of foreign races either improved or corrupted the native character. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“The name 'Dyak’ has been indiscriminately applied to all the wild people on the island of Borneo; but as the term is never so used by themselves, and as they differ greatly, not only in name, but in their customs and manners, we will briefly, in the first instance, mention the various distinct nations, the general locality of each, and some of their distinguishing peculiarities.-

“The Dyak are divided into Dyak Darrat and Dyak Laut, or land and sea Dyaks. The Dyak Lauts, as their name implies, frequent the sea; and it is needless to say much of them, as their difference from the Dyak Darrat is a difference of circumstances only. The tribes of Sarebus and Sakarran, whose rivers are situated in the deep bay between Tanjong Sipang and Tanjorig Sirak, are powerful communities, and dreadful pirates, who ravage the coast in large fleets, and murder and rob indiscriminately; but this is by no means to be esteemed a standard of Dyak character. In these expeditions the Malays often join them, and they are likewise made the instruments for oppressing the Laut tribes. The Sarebus and Sakarran are fine men, fairer than the Malays, with sharp keen eyes, thin lips, and handsome countenances, though frequently marked by an expression of cunning. The Balows and Sibnowans are amiable tribes, decidedly warlike, but not predatory; and the latter combines the virtues of the Dyak character with much of the civilisation of the Malays.-

RELATED ARTICLES:

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAK LIFE AND CULTURE: FAMILY, ART, FOOD, LONGHOUSES factsanddetails.com

DIFFERENT DAYAK GROUPS: KENYAH, KAYAN, MONDANG factsanddetails.com

NGAJU DAYAKS: LIFE, CULTURE, RELIGION, ART factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DUSUN PEOPLE: LIFE, CULTURE, SOCIETY, HISTORY, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL AND EASTERN SARAWAK (NORTHERN factsanddetails.com

SABAH: ORANGUTANS, GREAT DIVING AND ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Dayak Groups in the 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “1) The Dusun, or villagers of the northern extremity of the island, are a race of which Mr. Brooke knows nothing personally; but the name implies that they are an agricultural people: they are represented as not being tattooed, as using the sumpitan, and as having a peculiar dialect. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

Murut inhabit the interior of Borneo proper. They are not tattooed, always use the sumpitan [blowgun], and have a peculiar dialect. In the same locality, and resembling the Murut, are some tribes called the Basaya.-

Kadians (or Idaans of voyagers) use the sumpitan, and have likewise a peculiar dialect; but in other respects they nowise differ from the Borneons, either in religion, dress, or mode of life. They are, however, an industrious, peaceful people, who cultivate the ground in the vicinity of Borneo Proper, and nearly as far as Tanjong Barram. The wretched capital is greatly dependent upon them, and, from their numbers and industry, they form a valuable population. In the interior, and on the Balyet river, which discharges itself near Tanjong Barram, is a race likewise called Radian, not converted to Islam, and which still retains the practice of "taking heads."

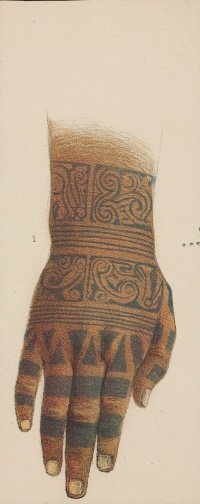

Eayans are the most numerous, the most powerful, and the most warlike people in Borneo. They are an inland race, and their locality extends from about sixty miles up the country from Tanjong Barram to the same extent farther into the interior, in latitude 3̊ S(f n., and thence across the island to probably a similar distance from the eastern shore. Their customs, manners, and dress are peculiar, and present most of the characteristic features of a wild and independent people. The Malays of the n.w. coast fear the Kayans, and rarely enter their country; but the Millanows are familiar with them, and there have thence been obtained many particulars respecting them. They are represented as extremely hospitable, generous and kind to strangers, strictly faithful to their word, and honest in their dealings; but on the other hand, they are fierce and bloodthirsty, and when on an expedition, slaughter without sparing. The Kayans are partially tattooed, use the sumpitan, have many dialects, and are remarkable for the strange and apparently mutilating custom adopted by the males, and mentioned by Sir Stamford Raffles.-

Millanows are southward and westward of Barram. "They are the inhabit the rivers not far from the sea. They are, generally speaking, an intelligent, industrious, and active race, the principal cultivators of sago, and gatherers of the famous camphor barus. Their locality extends from Tanjong Barram to Tanjong Sirak. In person they are stout and well made, of middling height, round good-tempered countenances, and fairer than the Malays. They have several dialects amongst them, use the sumpitan, and are not tattooed. They retain the practice of taking heads, but they seldom seek them, and have little of the ferocity of the Eayan.-

“6) In the vicinity of the Kayans and Millanows are some wild tribes, called the Tatows, Balanian, Eanowit, &c. They are probably only a branch of Kayans, though differing from them in being elaborately tattooed over the entire body. They have peculiar dialects, use the sumpitan, and are a wild and fierce people.-

Differences Between Different Dayak Groups in the 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “The Dyak Laut do not tattoo, nor do they use the sumpitan; their language assimilates closely to the Malay, and was doubtless originally identical with that of the inland tribes. The name of God amongst them is Battara (the Avatara of the Hindoos). They bury their dead, and in the graves deposit a large portion of the property of the deceased, often to a considerable value in gold ornaments, brass guns, jars, and arms. Their marriage-ceremony consists in two fowls being killed, and the forehead and breast of the young couple being touched with the blood; after which the chief, or an old man, knocks their heads together several times, and the ceremony is completed with mirth and feasting. In these two instances they differ from the Dyak Darrat.[Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“The locality of the Dyak Darrat may be marked as follows: The Fontiana river from its mouth, is traced into the interior towards the northward and westward, until it approaches at the furthest within 100 miles of the north-west coast; a line drawn in latitude 8̊ n. till it intersects the course of the Fontiana river will point out the limit of the country inhabited by the Dyak. Within this inconsiderable portion of the island, which includes Sambas, Landak, Fontiana, Sangow, Sarawak, &c, are numerous tribes, all of which agree in their leading customs, and make use of nearly the same dialect.-

“It must be observed that the Dyak also differs from the Kayan in not being tattooed; and from the Kayan Millanows, &c„ in not using the national weapon— the sumpitan. The Kayan and the Dyak, as general distinctions, though they differ in dialect, in dress, in weapons, and probably in religion, agree in their belief of similar omens, and, above all, in their practice of taking the heads of their enemies; but with the Kayan this practice assumes the aspect of an indiscriminate desire of slaughter, whilst with the Dyak it is but the trophy acquired in legitimate warfare. The Kadians form the only exception to this rule, in consequence of their conversion to Islam; and it is but reasonable to suppose, that with a slight exertion in favour of Christianity, others might be induced to lay aside this barbarous custom.-

“We know little of the wild tribes of Celebes beyond their general resemblance to the Eayans of the east coast of Borneo; and it is probable that the Eayans are the people of Celebes, who, crossing the Strait of Makassar, have in time by their superior prowess possessed themselves of the country of the Dyaks. Mr. Brooke (from whom I am copying this sketch) is led to entertain this opinion from a slight resemblance in their dialects to those used in Celebes, from the difference in so many of their customs from those of the Dyaks.-

Visiting Dayak Country in the 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: "Feb. 1st. — Started after breakfast, and paddled against a strong current past Tundong, and, some distance above, left the main stream and entered the branch to the right, which is narrower, and rendered difficult of navigation by the number of fallen trees which block up the bed, and which sometimes obliged us to quit our boat, and remove all the kajang covers, so as to enable us to haul the boat under the huge trunks. The main stream was rapid and turbid, swollen by a fresh, and its increase of volume blocked up the waters of the tributary, so as to render the current inconsiderable. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“The Dyaks have thrown several bridges across the rivers, which they effect with great ingenuity; but I was surprised on one of these bridges to observe the traces of the severe flood which we had about a fortnight since. The water on that occasion must have risen twenty feet perpendicularly, and many of the trees evidently but recently fallen, are the effects of its might. The walk to Rat, or Ra-at, is about two miles along a decent path. Nothing can be more picturesque than the hill and the village. The former is a huge lump (I think of granite), almost inaccessible, with bold bare sides, rising out of a rich vegetation at the base, and crowned with trees. The height is about 500 feet; and about a hundred feet lower is a shoulder of the hill on which stands the eagle- nest-like village of Ba-at, the ascent to which is like climbing by a ladder up the side of a house. This is one of the dwelling-places of the Sow Dyaks, a numerous but dispersed tribe. Their chief, or Orang Kaya, is an imbecile old man, and the virtual headship is in the hands of Nimok, of whom more hereafter. Our friends seemed pleased to see us, and Nimok apologised for so few of his people being present, as the harvest was approaching; but being anxious to give a feast on the occasion of my first visit to their tribe, it was arranged that to-morrow I should shoot deer, and the day following return to the mountain. The views on either side from the village are beautiful — one view enchanting from its variety and depth, more especially when lighted up by the gleam of a showery sunshine, as I first saw it. Soon, however, after our arrival, the prospect was shut out by clouds, and a soaking rain descended, which lasted for the greater part of the night.-

"Qd. — Started after breakfast; and after a quiet walk of about three hours through a pleasant country of alternate hill and valley, we saw the valley of Nawang below us. Nawang is the property of the Singe Dyaks, and is cultivated by poor families, at the head of which is Niarak. The house contained three families, and our party was distributed amongst them, ourselves, i. e. Low, Crookshank, and myself, occupying one small apartment with a man, his wife, and daughter. The valley presented one of the most charming scenes to be imagined — a clearing amid hills of moderate elevation, with the distant mountains in the background; a small stream ran through it, which, being dammed in several places, enables the cultivator to flood his padi-fields.-

Dayak Farming and Hunting in the 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: The padi looked beautifully green. A few palms and plantains fringed the farm at intervals, whilst the surrounding hills were clothed in their native jungle. Here and there a few workmen in the fields heightened the effect; and the scene, as evening closed, was one of calm repose, and, I may say,] of peace. The cocoa-nut, the betel, the sago, and the gno or gomati, are the four favourite palms of the Dyaks. In their simple mode of life, these four trees supply them many necessaries and luxuries. The sago furnishes food; and, after the pith has been extracted, the outer part forms a rough covering for the rougher floor, on which the farmer sleeps. The leaf of the sago is preferable for the roofing of houses to the nibong. The gomati, or gno, gives the black fibre which enables the owner to manufacture rope or cord for his own use; and over and above, the toddy of this palm is a luxury daily enjoyed. When we entered, this toddy was produced in large bamboos, both for our use and that of our attendant Dyaks; I thought it, however, very bad. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“In the evening we were out looking for deer, and passed many a pleasant spot which once was a farm, and which will become a farm again. These the Dyaks called rapack, and they are the favourite feeding-grounds of the deer. To our disappointment we did not get a deer, which we had reckoned on as an improvement to our ordinary dinner-fare. A sound sleep soon descended on our party, and the night passed in quiet; but it is remarkable how vigilant their mode of life renders the Dyak. Their sleep is short and interrupted; they constantly rise, blow up the fire, and look out on the night: it is rarely that some or other of them are not on the move.-

“Yearly the Dyaks take new ground for their farm; yearly they fence it in, and undergo the labour of reclaiming new land; for seven years the land lies fallow, and then may be used again. What a waste of labour I more especially in these rich and watered valleys, which, in the hands of the Chinese, might produce two crops yearly.-

Tumma Dyaks

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “This cruise being over, I established myself quietly at Sarawak. The country is peaceable; trade flourishes; the Dyaks are content; the Malays greatly increased in number — in short, all goes well. I received a visit from Lingire, a Dyak chief of Sarebus. At first he was shy and somewhat suspicious; but a little attention soon put him at his ease. He is an intelligent man; and I hail with pleasure his advent to Sarawak, as the dawn of a friendship with the two pirate tribes. It is not alone for the benefit of these tribes that I desire to cultivate their friendship, but for the greater object of penetrating the interior through their means. There are no Malays there to impede our progress by their lies and their intrigues; and, God willing, these rivers shall be the great arteries by which civilisation shall be circulated to the heart of Borneo.-

“4th. — The Dyaks of Tumma, a runaway tribe from Sadong, came down last night, as Bandar Cassim of Sadong wishes still to extract property from them. Bandar Cassim I believe to be a weak man, swayed by stronger-headed and worse rascals; but, now that Seriff Sahib and Muda Hassim are no longer in the country, he retains no excuse for oppressing the poor Dyaks. Si Nankan and Tumma have already flown, and most of the other tribes are ready to follow their example, and take refuge in Sarawak. I have fully explained to the Bandar that he will lose all his Dyaks if he continues his system of oppression, and more especially if he continues to resort to that most hateful system of seizing the women and children.-

“I had a large assembly of natives, Malay and Dyaks, and held forth many good maxims to them. At present, in Sarawak, we have Balows and Sarehus, mortal enemies; Lenaar, our extreme tribe, and our new Sadong tribe of Tumma. Lately we had Kantoss, from near Sarambowi in the interior of Pontiana; Undops, from that river; and Badjows, from near Lantang — tribes which had never thought of Sarawak before, and perhaps never heard the name. Oh, for power to pursue the course pointed out !

“6th — The Julia arrived, much to my relief; and Mr. Low, a botanist and naturalist, arrived in her. He will be a great acquisition to our society, if devoted to these pursuits. The same day that the Julia entered, the Ariel left the river. I dismissed the Tumma Dyaks; re- warned Bandar Cassim of the consequences of his oppression; and had a parting interview with Lingire. I had another long talk with Lingire, and did him honour by presenting him with a spear and flag, for I believe he is true, and will be useful; and this Orang Kaya Pa-muncha, the most powerful of these Dyaks, must be mine. Lingire described to me a great fight he once had with the Kayans, on which occasion he got ninety-one heads, and forced a large body of them to retire with inferior numbers* I asked him whether the Kayans used the sumpitan ? he answered, c Yes.' c Did many of your men die from the wounds ?' * No; we can cure them/ This is one more proof in favour of Mr. Crawfurd's opinion that this poison is not sufficiently virulent to destroy life when the arrow is (as it mostly is) plucked instantly from the wound.-

“26th. — Lingi, a Sakarran chief, arrived, deputed (as he asserted, and I believe truly) by the other chiefs of Sakarran to assure me of their submission and desire for peace. He likewise stated, that false rumours spread by the Malays agitated the Dyaks; and the principal rumour was, that they would be shortly attacked again by the white men. These rumours are spread by the Sariki people, to induce the Sakarrans to quit their river and take refuge in the interior of the Kejong; and once there, the Sakarrans would be in a very great measure at the mercy of the Sariki people. This is a perfect instance of Malay dealing with the Dyaks; but in this case it has failed, as the Sakarrans are too much attached to their country to quit it. I am inclined to believe their professions; and at any rate it is convenient to do so and to give them a fair trial.-

Lundu Dyaks

Henry Keppel wrote in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “We found the Samarang off the Morotaba entrance, when' Mr. Brooke and myself became the guests of Sir Edward Belcher for several days, during which time we made excursions to all the small islands in that neighbourhood, discovered large quantities of excellent oysters, and had some very good hog-shooting. Afterwards, accompanied by the boats of the Samarang, we paid a visit to the Lundu Dyaks, which gave them great delight. They entertained us at a large feast, when the whole of the late expedition was fought over again, and a war-dance with the newly-acquired heads of the Sakarran pirates was performed for our edification. Later in the evening, two of the elder chiefs got up, and, walking up and down the long gallery, commenced a dialogue, for the information, as they said, of the women, children, and poorer people who were obliged to remain at home. It consisted in putting such questions to one another as should elicit all the particulars of the late expedition, such as, what had become of different celebrated Sakarran chiefs? (whom they named) how had they been destroyed? how did they die? by whom had they been slain? All these inquiries received the most satisfactory replies, in which the heroic conduct of themselves and the white men were largely dwelt upon. While this was performing, the two old warriors, with the heads of their enemies suspended from their shoulders like a soldier's cartouch - box, stumped up and down, striking the floor with their clubs, and getting very excited. How long it lasted none of our party could tell, as one and all dropped off to sleep during the recital. Mr. Brooke has given so good a description of these kind and simple people that I need not here further notice them. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“Shortly after our return to the Samarang, she, getting short of provisions, sailed for Singapore, and Mr. Brooke and myself went up to Sarawak, where the Dido was still lying. Great rejoicings and firing of cannon, as on a former occasion, announced our return; and after paying our respects to the Rajah, we visited the Tumangong and Patingis.-

“A curious ceremony is generally performed on the return of the chiefs from a fortunate war expedition, which is not only done by way of a welcome back; but is supposed to ensure equal success on the next excursion. This ceremony was better performed at the old Tumangong's than at the other houses. After entering the principal room, we seated ourselves in a semicircle on the mat floor, when the old chiefs three wives advanced to welcome us with their female relatives, all richly and prettily dressed in sarongs suspended from the waist, and silken scarfs worn gracefully over one shoulder, just hiding or exposing as much of their well-shaped persons as they thought most becoming. Each of these ladies in succession taking a handful of yellow rice, threw it over us, repeating some mystical words, and dilating on our heroic deeds, and then they sprinkled our heads with gold-dust. This is generally done by grating a lump of gold against a dried piece of shark's skin. Two of these ladies bore the pretty names of Inda and Amina. Inda was young, pretty, and graceful; and although she had borne her husband no children, she was supposed to have much greater influence over him than the other two. Report said that she had a temper, and that the Tumangong was much afraid of her; but this may have been only Sarawak scandal. She brought her portion of gold-dust already grated, and wrapped up in a piece of paper, from which she took a pinch; and in reaching to sprinkle some over my head, she, by accident, put the prettiest little foot on to my hand, which, as she wore neither shoes nor stockings, she did not hurt sufficiently to cause me to withdraw it. After this ceremony we (the warriors) feasted and smoked together, attended on by the ladies.-

Conferences with Dyak Chiefs in the 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “13th. — The Tumangong returned from Sadong, and brought me a far better account of that place than I had hoped for. It appears that they really are desirous to govern well, and to protect the Dyaks; and fully impressed with the caution I gave them, that unless they protect and foster their tribes, they will soon lose them from their removal to Sarawak. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“One large tribe, the Maluku, a branch of the Sibnowans, are, it appears, very desirous of being under my protection. It is a tempting offer, and I should like to have them; but I must not deprive the rulers of Sadong of the means of living comfortably, and the power of paying revenue. Protect them I both can and will. There are great numbers of Sarawak people at Sadong, all looking out for birds-nests; new caves have been explored; mountains ascended for the first time in the search. It shews the progress of good government and security, and, at the same time, is characteristic of the Malay character. They will endure fatigue, and run risks, on the chance of finding this valuable commodity; but they will not labour steadily, or engage in pursuits which would lead to fortune by a slow progress.-

“15th. — Panglima Laksa, the chief of the Undop tribe, arrived, to request, as the Badjows and Sakarrans had recently killed his people, that I would permit him to retort. At the same time came Ahong Kapi, the Sakarran Malay, with eight Sakarran chiefs, named Si Miow, one of the heads, and the rest Tadong, Lengang, Barunda, Badendang, Si Bunie, Si Ludum, and Kuno, the representatives of other heads. Nothing could he more satisfactory than the interview, just over. They denied any knowledge or connexion with the Badjows, who had killed some Dyaks at Undop, and said all that I could desire. They promised to ohey me, and look upon me as their chief; they desired to trade, and would guarantee any Sarawak people who came to their river; but they could not answer for all the Dyaks in the Batang Lupar. It is well known, however, that the Batang Lupar Dyaks are more peaceable than those of Sakarran, and will be easily managed; and as for the breaking out of these old feuds, it is comparatively of slight importance, compared to the grand settlement; for as our influence increases we can easily put down the separate sticks of the bundle. There is a noble chance, if properly used I It may be remarked that many of their names are from some peculiarity of person, or from some quality. Tadong is a poisonous snake; but, on inquiry, I found the young chief so named had got the name from being black. They are certainly a finelooking race.-

“17th. — Plenty of conferences with the Sakarran chiefs; and, as far as I can judge, they are sincere in the main, though soma reserves there may be. Treachery I do not apprehend from them; but, of course, it will be impossible, over a very numerous, powerful, and warlike tribe, to gain such an ascendancy of a sudden as at once to correct their evil habits." -

Exploitation of Dyaks in the 1840s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “The Dyaks have from time immemorial been looked upon as the bondsmen of the Malays, and the Rajahs consider them much in the same light as they would a drove of oxen — i. e. as personal and disposable property. They were governed in Sarawak by three local officers, called the Patingi, the Bandar, and the Tumangong. To the Patingi they paid a small yearly revenue of rice, but this deficiency of revenue was made up by sending them a quantity of goods — chiefly salt, Dyak cloths, and iron — and demanding a price for them six or eight times more than their value. The produce collected by the Dyaks was also monopolised, and the edible birds-nests, bees-wax, &c. &c, were taken at a price fixed by the Patingi, who more- over claimed mats, fowls, fruits, and every other necessary at his pleasure, and could likewise make the Dyaks work for him for merely a nominal remuneration. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“This system, not badly devised, had it been limited within the bounds of moderation, would have left the Dyaks plenty for all their wants; or had the local officers known their own interest, they would have protected those upon whom they depended for revenue, and under the worst oppression of one man the Dyaks would have deemed themselves happy. Such unfortunately was not the case; for the love of immediate gain overcame every other consideration, and by degrees oldestablished customs were thrown aside, and new ones substituted in their place. When the Fatingi had received all he thought proper to extort, his relatives first claimed the right of arbitrary trade, and gradually it was extended as the privilege of every respectable person in the country to serra 1 the Dyaks. The poor Dyak, thus at the mercy of half the Malay population, was never allowed to refuse compliance with these demands; he could plead neither poverty, inability, nor even hunger, as an excuse, for the answer was ever ready: “Give me your wife or one of your children;" and in case he could not supply what was required, the wife or the child was taken, and became a slave.-

“Many modes of extortion were resorted to; a favourite one was convicting the Dyak of a fault and imposing a fine upon him, Some ingenuity and much trickery were shewn in this game, and new offences were invented as soon as the old pleas would serve no longer: for instance, if a Malay met a Dyak in a boat which pleased him, he notched it, as a token that it was his property; in one day, if the boat was a new one, perhaps three or more would place their marks on it; and as only one could get it, the Dyak to whom the boat really belonged had to pay the others for his fault. This, however, was only “a fault" whereas, for a Dyak to injure a Malay, directly or indirectly, purposely or otherwise, was a high offence, and punished by a proportionate fine. If a Dyak's house was in bad repair, and a Malay fell in consequence and was hurt, or pretended to be hurt, a fine was imposed; if a Malay in the jungle was wounded by the springs set for a wild boar, or by the wooden spikes which the Dyaks for protection put about their village, or scratched himself and said he was injured, the penalty was heavy; if the Malay was really hurt, ever so accidentally, it was the ruin of the Dyak. And these numerous and uninvited guests came and went at pleasure, lived in free quarters, made their requisitions, and then forced the Dyak to carry away for them the very property of which he had been robbed.-

“This is a fair picture of the governments under which the Dyaks live; and although they were often roused to resistance, it was always fruitless, and only involved them in deeper troubles; for the Malays could readily gather a large force of sea Dyaks from Sakarran, who were readily attracted by hope of plunder, and who, supported by the firearms of their allies, were certain to overcome any single tribe that held out. The misfortunes of the Dyaks of Sarawak did not stop here. Antimony-ore was discovered; the cupidity of the Borneons was roused; then Fangerans struggled for the prize; intrigues and dissensions ensued; and the inhabitants of Sarawak in turn felt the very evil they had inflicted on the Dyaks; whilst the Dyaks were compelled, amidst their other wrongs, to labour at the ore without any recompense, and to the neglect of their rice r cultivation. Many died in consequence of this compulsory labour, so contrary to their habits and inclinations; and more would doubtless have fallen victims, had not civil war rescued them from this evil, to inflict upon them others a thousand times worse.-

“Extortion had before been carried on by individuals, but now it was systematised; and Fangerans of rank, for the sake of plunder, sent bodies of Malays and Sakarran Dyaks to attack the different tribes. The men were slaughtered, the women and children carried off into slavery, the villages burned, the fruit-trees cut down, and all their property destroyed or seized. The Dyaks could no longer live in tribes, but sought refuge in the mountains or the jungle, a few together; and as one of them pathetically described it — "We do not live," he said, "like men; we are like monkeys; we are hunted from place to place; we have no houses; and when we light a fire, we fear the smoke will draw, our enemies upon us." On infliction of cutting down the fruit-trees. Houses can be rebuilt, with its rude and ready materials, in a few weeks; but the latter, from which the principal subsistence of the natives is gathered, cannot be suddenly restored, and thus they are reduced to starvation.-

Dayak Suffering and Population Decline in the 1940s

James Brooke wrote in his journal in “Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido for the Suppression of Piracy”: “In the course of ten years, under the circumstances detailed, from enforced labour, from famine, from slavery, from sickness, from the sword, — one half of the Dyak population disappeared; and the work of extirpation would have gone on at an accelerated pace, had the remnant been left to the tender mercies of the Pangerans; but chance (we may much more truly say, Providence) led our countryman to this scene of misery, and enabled him, by circumstances far removed beyond the grounds of calculation, to put a stop to the sufferings of an amiable people. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“The grounds for this opinion are an estimate personally made amongst the tribes, compared with the estimate kept by the local officers before the disturbance arose; and the result is, that only two out of twenty tribes have not suffered, whilst some tribes have been reduced from 330 families to 50; about ten tribes have lost more than half their number; one tribe of 100 families has lost all, its women and children made slaves; and one tribe, more wretched, has been reduced from 120 families to 2, that is 16 persons; whilst two tribes have entirely disappeared. The list of the tribes and their numbers formerly and now are as follows:— Suntah, 330—50; Sanpro, 100—69; Sigo, 80—28; Sabungo, 60 — 33; Brang, 50—22; Sinnar, 80—34; Stang, 80—30; Samban, 60—34; Tubbia, 80—30; Goon, ,40— 25; Bang, 40— 12; Kuj-juss, 35—0; Lundu, 80—2; Sow, 200— 100; Sarambo, 100—60; Bombak, 35—35; Paninjow, 80—40; Singe, 220—220; Pons, 20—0; Sibaduh, 25—25. Total, for merly, 1795 — now, 849 families; and reckoning eight persons to each family, the amount of population will be, formerly, 14,360 — now, 6792: giving a decrease of population in ten years of 546 families, or 7568 persons I

The peaceful and gentle aborigines — how can I speak too favourably of their improved condition? These people, who, a few years since, suffered every extreme of misery from war, slavery, and starvation, are now comfortably lodged, arid comparatively rich, A stranger might now pass from village to village, and he would receive their hospitality, and see their padi stored in their houses. He would hear them proclaim their happiness, and praise the white man as their friend and protector. [Source: “The Expedition to Borneo of H.M.S. Dido For the Suppression of Piracy” by Henry Keppel and James Brooke (1847)-]

“Since the death of Paremham, no Dyak of Sarawak lost his life by violence, until a month since, when two were cut off by the Sakarran Dyaks. None of the tribes have warred amongst themselves; and I believe their war excursions, to a distance in the interior have been very few, and those undertaken by the Sarambos. What punishment is sufficient for the wretch who finds this state of things so baleful as to attempt to destroy it ? Yet such a wretch is Seriff Sahib. In describing the condition of the Dyaks, I do not say that it is perfect, or that it may not be still further improved; but with people in their state of society innovations ought not rashly or hastily to be made; as the civilised being ought constantly to bear in mind, that what is clear to him is not clear to a savage; that intended benefits may be regarded as positive injuries; and that his motives are not, and scarcely can be, appreciated. The greatest evil, perhaps, from which the Dyaks suffer, is the influence of the Datus or chiefs; but this influence is never carried to oppression, and is only used to obtain the expensive luxury of birds-nests at a cheap rate. In short, the Dyaks are happy and content; and their gradual development must now be left to the work of time, aided by the gentlest persuasion, and advanced (if attainable) by the education of their children."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025