DUSUN

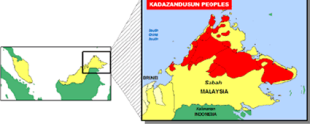

The Dusun are the largest of Sabah’s 12 indigenous groups. Also known as the Idäan, Kadazan, Kalamantan, Kadazandusans, Kiaus, Piasau Id'an, Saghais, Sipulotes, Sundayak, Tambunwhas (Tambunaus) and Tuhun Ngaavi, they are former headhunters and are outnumbered in Sabah only by Malays. Some Dusun live in northeastern Kalimantan. The Dusun language belongs to the Northwestern Group of Austronesian languages. It is related to languages spoken in Borneo, Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Madagascar. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993~]

Dusun people are considered part of the broader Dayak ethnic group. The Dusun inhabit northern Borneo and speak a range of regional dialects belonging to the Austronesian language family. In the Penampang dialect, the Dusun refer to themselves as Tuhun Ngaavi, meaning “the people.” Internal distinctions among Dusun communities are commonly expressed through geographic identifiers such as Tambunan, Penampang, or Tempassuk, as well as through differences in subsistence practices. Communities dependent on irrigated wet rice cultivation describe themselves as tuhun id ranau (people of the wet rice fields), while those practicing swidden or hill rice agriculture are known as tuhun id sakid (people of the hill rice fields). ~

The term “Dusun” itself originated in nineteenth-century European usage, derived from the Malay expression orang dusun (people of the orchards), and was adopted as a general reference by colonial administrators and scholars. More recent ethnological literature has continued to use “Dusun” or has subsumed the group within a broader cultural category sometimes referred to as the Kalimantan nation, which includes the Kalabit, Milanau, and Murut peoples of northern Borneo. Following the incorporation of the former British colony of North Borneo into Malaysia as the state of Sabah on 16 September 1963, many Dusun began to identify themselves as “Kadazan” in order to distinguish their culture and society from those of other Indigenous groups in Sabah. Today, a significant number of Dusun regard the term “Dusun” as a colonial legacy and as a pejorative label that fails to acknowledge their long history and deep environmental knowledge as a people well adapted to local ecological conditions.

RELATED ARTICLES:

TRIBAL PEOPLE OF BORNEO: LONGHOUSES, SAGO, ART factsanddetails.com

BORNEO ETHNIC GROUPS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES factsanddetails.com

PENAN: RELIGION, CULTURE, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

PENAN LIFE AND SOCIETY: FOOD, CUSTOMS, VILLAGES factsanddetails.com

PENAN AND THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS: HISTORY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

DAYAKS IN THE 1840s factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, RELGION, CULTURE, HEADHUNTING factsanddetails.com

IBAN PEOPLE: LIFE, SOCIETY, VILLAGES, FOOD factsanddetails.com

KALIMANTAN (INDONESIAN BORNEO): GEOGRAPHY, DEMOGRAPHY, GROUPS factsanddetails.com

SABAH: ORANGUTANS, GREAT DIVING AND ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Dusun Population and Where They Live

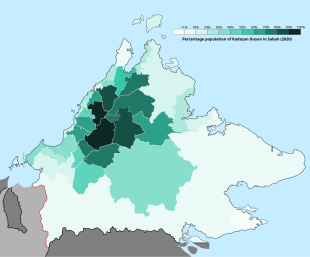

Kadazan-Dusuns make up about 30 percent of Sabah’s population. They consist of two tribes; the Kadazan and the Dusun, who were grouped together as they both share the same language and culture. However, the Kadazan are mainly inhabitants of flat valley deltas, which are conducive to paddy field farming, while the Dusun traditionally lived in the hilly and mountainous regions of interior Sabah. [Source: Malaysian Government Tourism]

According to Malaysian government statistics the total population of Dusun, including Kadazan, was 38.7 percent of of the indigenous peoples of Sabah, which in turn make up 51.9 percent of the population of Sabah. The 2010 census counted 555,647 Dusun. According to the Christian group Joshua Project, in the early 2020s, the Kadazan Dusun population was 85,000, the Malang Dusun population was 5,800, and the Deyah Dusun population in northern Kalimantan was 38.000. [Source: Wikipedia, Joshua Project]

The Dusun population is concentrated in the Malaysian state of Sabah, which covers an area of approximately 73,710 square kilometres at the northern tip of Borneo. Dusun settlements are found along Sabah’s narrow northern and eastern coastal plains, as well as in the interior mountain ranges and valleys, with smaller communities located near the headwaters of the Labuk and Kinabatangan rivers. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993~]

According to the 1960 census conducted by the British colonial administration of North Borneo, the total population of what is now Sabah was 454,421, of whom 306,498 were classified as members of “indigenous tribes.” The Dusun constituted the largest of the twelve Indigenous groups recorded, numbering 145,229 individuals, or about 45 percent of the Indigenous population and roughly 32 percent of the total population. ~

By 1980, the population of Sabah had increased to 955,712, although the census did not provide detailed figures for the twenty-eight groups categorized collectively as pribumi, or Indigenous peoples, who together numbered 742,042. In 1990, the Dusun constituted the largest ethnic group in Sabah, followed by the Chinese population.~

Dusun History

The precise origins of the Dusun population remain uncertain. Archaeological and physical anthropological evidence, together with historical and comparative studies, suggest that the Dusun descend from groups that migrated into northern Borneo in successive waves around four to five thousand years ago, and possibly earlier. These early migrants introduced a Neolithic, food-producing way of life centered on swidden cultivation, supplemented by hunting and foraging. Cultural change among the Dusun has been underway for a long period, shaped by sustained contact with neighboring and distant societies. Historical sources indicate that such interactions were especially significant in the western and northern coastal areas of present-day Sabah, where the Dusun came into contact with Indian, Chinese, Malay, and later European peoples. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Sustained and systematic contact with Europeans did not occur until the mid-nineteenth century, when British interests moved to secure trade routes through the South China Sea. In 1881, British investors established a private chartered company that governed northern Borneo as a sovereign entity until 15 July 1946, when the territory became a British colony. British colonial rule continued for a further 17 years, ending in September 1963 with the incorporation of North Borneo as the state of Sabah within Malaysia. During the 82 years of regular contact with British institutions, power and law were largely imposed with limited regard for Dusun customary traditions. At the same time, these encounters integrated the Dusun into a Malaysian political framework, introduced them to a national language, Bahasa Melayu, and exposed them to state policies that emphasized Muslim religious traditions, values, and social practices.

In the 1980s the chief minister of Sabah was Mr. Joseph Pairin Kitingan, a 49-year-old Dusun who was a Christian and the first Dusun to qualify as a lawyer in Malaysia. First elected in 1985 in an unexpected victory over candidates from two Muslim-led political parties, Mr. Kitingan’s party, Parti Bersatu Sabah, gained control of the state government by winning a majority of assembly seats. Following legal challenges by members of the previous state government and their supporters, a new assembly election was called in 1986. During the two-month campaign, violent incidents occurred, including riots and bombings carried out by political activists supporting the main opposition party, Bersatu Rakyat Jelata. In the elections held in May 1986, Parti Bersatu Sabah increased its majority in the state assembly, and Mr. Kitingan remained chief minister. In June 1986, the party joined Barisan Nasional, the National Front coalition of 13 parties that formed the ruling alliance in Malaysia. As a result, the Dusun became increasingly embedded in a complex nation-state political system extending well beyond their traditional sociopolitical framework.

Dusun Headhunting

Headhunting was practiced by the Dusun up until World War II even though the practice was outlawed by the British in the late 19th century. It was usually the climax of a conflict between communities that was solved through raiding and hand to and combat.

Traditionally, conflicts were often the result of a perceived imbalance, disharmony or ill fortune in one community believed to be the caused an individual in another community. The Dusun organized raiding parties of men who sought hand-to-hand combat with individuals, social groups, or entire communities believed to have caused an imbalance in personal or communal fortune (nasip tavasi) and luck (ki nasip). Such armed confrontations were generally undertaken to restore the fate or luck of individuals or communities that had been rendered unfavorable (aiso nasip, talat) through the actual or perceived actions of others.

The object of raids was to secure trophies, preferable the heads of enemies killed in close combat which could be publicly displayed as symbols of the successful restoration of good fortune and luck. Heads taken in this way were treated with great reverence and special care. They were usually stored in a special place, including the eaves of houses, and were used for special rituals in which they were the focal point and regarded as integral to maintaining harmony.

After 1881, the Chartered Company undertook determined efforts to suppress head-taking and related forms of combat. Although these measures met with only limited success until shortly before World War II, such practices were eventually brought to an end. Since that time, organized armed conflict of this kind has not been a feature of Dusun life.

Monsopiad, the Legendary Headhunter

The famous warrior Monispiad is said to have taken 42 heads about 300 years ago. According to ThingsAsian.com: “Legend told that many centuries ago, a lady named Kizabon was pregnant. She lived in a house with her husband, Dunggou. On the roof of their house, a sacred Bugang bird made its nest and stayed there throughout Kizabon's pregnancy.When the child was due to be born, the Bugang birds hatched as well. The father of the child took the sign as a good omen and that this was a sign that his newborn son would have special powers. He named his son, Monsopiad. The father paid special care to the birds as well, and whenever his son took a bath, Dunggou would take the young birds down from their nest to have a bath with his son. When done, he later returned them to the safety of their nest. This was done diligently until the birds were strong enough to leave the nest. [Source: thingsasian.com ]

“The young boy grew up in the village Kuai (which is the grounds of the Village). His maternal grandfather was the headman of the village. However, their village was often plundered and attacked by robbers and due to the lack of warriors in the village, the villagers had to retreat and hide while the robbers ransacked their homes. But for Monsopiad, things were different. He was given special training and he turned out to be an excellent fighter and grew up to become a warrior. Well-equipped, he vowed to hunt down and fight off the warriors that had terrorized his village for so long. He will bring back their heads as trophies, he claimed, and hang them from the roof of his house!

“All he wanted in return was a warrior's welcome, where his success will be heralded by the blowing of bamboo trumpet. In order to prove that he really did as promised, three boys went with him as witnesses. Just as he had promised, Monsopiad's journey to rid his village of the robbers was a huge success and upon coming home, he was given a hero's welcome. He was so honored by the welcome that he proclaimed he will destroy all enemies to his village. Over the years, Monsopiad soon attained a reputation and there were no robbers or evil warriors who dared to challenge him. However, the urge to kill had gotten into Monsopiad's head and he simply could not stop himself from beheading more people. Very soon, he started provoking other men into fighting him so that he would have an excuse to kill and behead them.

“With his changed attitude, all the villagers and his friends became afraid of him. Left with no choice, the village got a group of brave warriors together and they plan to eliminate Monsopiad. Much as they respected Monospiad for his heroic deeds, yet they had no choice for he had slowly turned into a threat. One night as planned, the warriors moved in for the kill as Monsopiad was resting in his house. As they attacked him, he fought back fiercely but realized that he had lost his special powers that were bestowed upon him by the Bugang bird. By abusing his gift, he was left powerless and it was that very night that Monsopiad's life ended. Despite his downfall, the villagers still loved Monsopiad for all that he had done for them. All in all, he collected 42 heads and a great feat that was! In honor and memory of a once great warrior, a monument was erected and the village was renamed after him.”

Dusun Religion

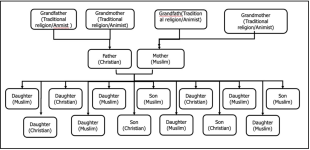

Some Dusun are Christians. Some are Muslims. Many retain their traditional animist beliefs. According to the Christian group Joshua Project,10 to 50 percent of Kadazan Dusun are Christians and 5 to 10 percent are Evangelicals;10 to 50 percent of Malang Dusun are Christians and 0.1 to 2 percent are Evangelicals; and 10 to 50 percent of Deyah Dusun in northern Kalimantan, Indonesia are Christians and 2 to 5 percent are Evangelicals. [Source: Joshua Project]

The Dusun have traditionally practiced animism, believing in a direct and ongoing relationship between the events of daily life and a complex realm of benevolent and malevolent supernatural beings and unseen forces. They hold that appropriate ritual and ceremonial actions can mediate between humans and these supernatural powers, allowing people to influence or even control events that cause illness, uncertainty, loss of fortune, pain, or fear.[Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Dusun conceptions of the universe include numerous harmful supernatural beings and forces thought to be responsible for personal crises such as accidents, illness, and death. These include entities believed to have existed since the creation of the world, as well as the souls of the dead who, because of evil deeds committed during life, are condemned by the creator being to wander eternally and engage in cannibalism. Alongside these malevolent forces, the Dusun also recognize a group of beneficial spirit beings that help maintain order in the universe and in everyday human life. The most important of these in daily practice is the “spirit of the rice,” a female entity regarded as the guardian of the rice crop and rice storehouse. Rituals performed in her name accompany key stages of rice cultivation, especially planting and harvest.

In addition, the Dusun traditionally believe in a distinct class of named supernatural beings whose characteristics and powers are well known to ritual specialists and are invoked in efforts to divine and influence events that may lead to life crises. A creator force, personified as a being called Asundu and endowed with immense power and a legendary history, is believed to have shaped the universe and to govern the destiny of all its inhabitants. A specific form of power derived from this creator is thought to be the source of the healing and restorative abilities of both female and male ritual specialists. This power is believed to reside in objects, places, and individuals, all of which must be treated with respect or avoided when possible. Special designations, known as apagun, and carved symbols are used to mark and protect such places or objects from unintended human contact. In contemporary times, many Dusun have converted to Christianity and therefore reject many traditional animistic beliefs and practices, while others have become Muslims.

Dusun Religious Practitioners and Ceremonies.

Within each Dusun community, certain men and women are recognized as possessing specialized knowledge of the rituals and ceremonies used to mediate between the human and supernatural worlds. These practices may involve spirit possession, the use of symbolic objects, and the recitation of lengthy sacred verses, and they often focus on individuals, places, or crops afflicted by illness or misfortune. Ritual effectiveness is believed to depend on the precise execution of prescribed procedures and the accurate recitation of ritual texts. Female ritual specialists generally concentrate on healing and divination related to individual illness and bad fortune, whereas male specialists tend to address misfortune or danger perceived to affect the wider community. The ritual verses recited by both men and women are often expressed in archaic forms of the Dusun language that are no longer widely understood, and mastery of them requires long apprenticeship under senior ritual specialists. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Priestesses known as bobohizans, who communicated with spirits, have traditionally been consulted when tribe members fell ill, had bad breath, or were having problems with their crops. They have also been asked to check for omens when a major decision was made such as moving a longhouse. The Dusun have a reputation for not preserving their culture. As of the early 2000s there were only a couple of dozen bobohizans left and many of them were no longer passing their skills on to the younger generation. Ceremonies: Public ritual performances are a regular part of Dusun life, many of them closely linked to the annual cycle of swidden and irrigated rice agriculture. Ceremonies marking major stages and transitions in the human life cycle, such as birth, marriage, and death, are also of central importance.

Illnesses has traditionally been believed to result from bad fortune, the actions of harmful supernatural beings and forces, and, in some cases, the malicious intentions of human adversaries. A wide range of medicinal remedies derived from plant and animal materials, prepared as lotions and poultices, is used to treat illness. Particular importance is attached to a type of swamp-plant root believed to possess magical and curative properties, which is employed by female ritual specialists in divination and healing practices.

Funerals and Beliefs About Death: The Dusun believe that after death the spirit of an individual travels to the supernatural world. There, the spirits of the dead are said to dwell near the creator being in a realm resembling the human world but free from disease, misfortune, crop failure, and warfare, where all things are perpetually renewed. Some spirits, however, are believed never to reach this destination, having been captured by harmful beings or consumed by cannibal spirits along the way. A formal period of mourning, accompanied by a series of rituals and ceremonial acts, is intended to assist the deceased in making a successful transition to life in the afterworld.

Dusun Society and Political Organization

Dusun society has traditionally been organized around several territorially based divisions that serve as focal points for the performance of specific ritual and ceremonial activities. These territorial units may include one or several mutual-aid groups, whose members cooperate in carrying out labor-intensive tasks such as house construction or field clearing. Social organization is also structured by age, sex, personal and family wealth, and region of residence. Seniority in age, for both women and men, plays an important role in social relations. Women are widely respected for their specialized knowledge of crafts, rituals, and ceremonial practices. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Traditionally, Dusun political authority has been organized at the level of the local community. In the past, little attention was given to broader sociopolitical units such as parish, district, province, or state. Communities are led by men chosen through informal, community-wide consensus, who hold formal office as headmen (mohoingon) with wide-ranging authority. This position is regarded as nonhereditary, with succession based on community approval rather than lineage.

Social Control within Dusun communities is maintained primarily through informal sanctions, including shame, mockery, gossip, ridicule, and, at times, social shunning. In addition, more formal mechanisms exist at the community level to address serious violations of traditional norms and values. The Dusun employ several methods for litigating complaints against individuals, drawing upon a body of abstract principles imbued with traditional moral authority, known as koubasan. This framework provides ethical legitimacy and binds all parties involved in litigation. Legal proceedings are conducted by the village leader, the mohoingon, who establishes the facts of a case and may administer one or more tests of truth. The leader has the authority to impose fines and various forms of punishment on those found guilty of violating customary behavior. Litigation is conducted as a public process, reinforcing communal accountability and social cohesion.

Dusun Family, Kinship and Marriage

Among the Dusun, the nuclear family is the minimal family unit occupying a household. Additional relatives may be incorporated into the nuclear family as the need arises, particularly if they are aged, ill, or handicapped. These relatives are expected to contribute in some way to the functioning of the household. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Descent in Dusun culture is bilateral, along both male and female lines. Kindred groups are also present and play an active role in the celebration of important events in an individual’s life. For the Dusun, a kindred group consists of relatives who recognize their connection to a particular person, regardless of whether the relationship is traced through male or female lines. In addition, the Dusun recognize specific social groups composed of descendants of a founding ancestor whose deeds are preserved in legend and folktale and recounted during ritual feasts and ceremonial occasions. Some land and movable property are owned in the name of these ancestor-oriented kin groups, which have traditionally regulated marriage among their members through a preference for endogamy. The Dusun traditionally employ Eskimo cousin terminology (which clearly distinguishes siblings from cousins but groups all cousins into one general "cousin" category) and place strong emphasis on relative age in social relations, extending special kin terms to unrelated individuals based on age differences.

Marriage is typically monogamous, although polygynous unions are permitted among older, wealthy men and younger women believed capable of bearing healthy children. Both arranged marriage and love matches occur. Couples often decide to marry in secret and go through an elaborate procedure to bring their parents on board. The groom’s family usually pays a substantial bride price. Divorce requires interdiction by community leaders

Marriage with any first or second cousin is prohibited, and unions with third cousins are generally regarded as distasteful. Within these constraints, individuals enjoy a degree of freedom in choosing marriage partners. Once a man and a woman agree to marry, often in secret, formal marriage negotiations are initiated by the man’s father, paternal grandfather, or father’s brother with the woman’s father, paternal grandfather, or father’s brother. Marriage involves a direct and substantial payment by the groom to the bride’s father. Marriages tend to be locally exogamous (outside the group). After marriage, couples usually establish an independent household near both families, although a newly married couple may initially reside with the groom’s father, and less often with the bride’s father, while accumulating sufficient resources to form their own household. The dissolution of marriage, other than through the death of a spouse, requires initial arbitration by a community leader, followed by a formal hearing if reconciliation fails. A ritual fine may be imposed on the individual judged to be at fault.

Childrearing: Parents generally share responsibility for the care of infants and young children. Older siblings frequently assist in caring for younger children when parents are away at work. Traditional childrearing emphasizes a prolonged period during which children are largely free from most tasks and subject to few behavioral restrictions. At about eleven or twelve years of age, however, children are expected to begin participating in daily work and to assume responsibilities as members of their families and communities. Before this age, children are regarded as naturally noisy, prone to illness, somewhat temperamental, easily offended, quick to forget, and inclined to wander. Parents attempt to shape this behavior through a wide range of physical and verbal rewards and punishments. Because infants and young children are not considered fully competent persons until around eleven or twelve years of age, they are not judged harshly or severely punished for misbehavior.

Inheritance: The Dusun traditionally adhere to the principle that all children should receive a fair share of their parents’ estates. A child who provides care for an aged parent prior to death may receive additional consideration in the distribution of property. A husband exercises little control over the property that his wife brings into a marriage. To address complex inheritance issues, the Dusun have developed and continue to employ a customary system for determining the equitable distribution of property.

Dusun Life, Villages, and Culture

The Dusun have traditionally lived in villages with an average of 300 to 400 people and ranged, in the 1950s, from a low of about 100 persons to over 1,000 persons.. Most Dusun communities are distinct, compact, and nucleated settlements located at the center of, or immediately adjacent to, their food-producing areas — typical swidden (slash and burn) plots. In Dusun villages, family members typically leave their homes at the start of the day to tend fields, carry out agricultural tasks, or forage and hunt in nearby forest areas. Traditional houses in both settings are constructed with hardwood support posts, split-bamboo walls and floors, and roofs made of bamboo tiles or atap palm thatch. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Longhouses or “divided longhouses” were the predominate style of house in the old days but now have all but vanished except in remote forest locations. Longhouse-style dwellings consisted of a series of nuclear-family apartments constructed on a single level, fronted by a shared veranda and covered by a common roof. In some swidden-based communities, several longhouses are clustered closely together.

Dusun communities whose subsistence is based on irrigated rice agriculture more often consist of multiple separate nuclear-family houses arranged in close proximity. These settlements resemble a “divided longhouse” form, in which family dwellings are no longer connected by a shared veranda or roof, and are commonly aligned along a footpath, frequently situated on a rise or bluff overlooking nearby rice fields. In such irrigated rice communities, coconut palms, fruit trees, and other useful plants are grown near the houses.

Dusun Art and house architecture incorporate forms and motifs shared with other Indigenous peoples of Borneo. Many of these designs are believed to embody a spiritual quality, known as id dasom ginavo, and to express deep understanding (ginavo) and respect for Dusun tradition, or koubasan. Traditional musical instruments include the bamboo mouth harp, a bamboo-and-gourd wind instrument, and gongs of various sizes, which were formerly obtained through trade with Chinese merchants. Dusun men have also traditionally practiced tattooing on the neck, forearms, and shoulders, using intricate designs associated with profound spiritual meanings.

Dusub Dances include Sumazau, a traditional dance of the Kadazan people. It is commonly performed at religious ceremonies and social gatherings and is traditionally intended to honor spirits for abundant rice harvests, to ward off evil influences, and to cure illness. Male and female dancers perform this slow, rhythmic, and hypnotic dance with gentle movements that imitate birds in flight.

Dusun Agriculture, Work and Economic Activity

Dusun have traditionally grown wet rice as their principal crop, using water buffalo to prepare their fields. They also have raised a variety of vegetables in home gardens and caught fish with traps. Men and women worked together in the fields with the men usually doing much of the heavy work. Women are responsible for most household tasks and have traditionally engaged in bamboo weaving crafts, while did things like heavy construction work, field clearing, burning, and irrigation maintenance. Men are expected to assist with childcare. Land tenure is based on individual ownership and inheritance of irrigated rice fields, but population growth has increased pressure on land, leaving many younger Dusun without access to farmland and prompting migration to urban areas such as Kota Kinabalu. Today, most Dusun work in normal jobs. Some are civil servants. [Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Rice is grown for daily consumption and is eaten several times each day. Seedlings are first raised in nursery plots and then transplanted by hand into small fields, typically less than a hectare in size, which are prepared jointly by women and men. Field preparation includes repairing the low earthen dikes that retain flowing water, as well as maintaining irrigation systems that divert water from nearby streams and rivers. These systems may carry water across ravines using bamboo or wooden conduits and require considerable practical knowledge of hydrodynamics, particularly when directing water to fields located at a distance from a stream.

Traditional wet-rice cultivation involves loosening the soil with hoes and plowing fields using flat-board harrows fitted with wooden teeth and pulled by water buffalo wearing woven rattan harnesses. Rice is harvested by hand and initially winnowed in the fields on woven split-bamboo mats. Additional winnowing may take place near grain storehouses, where surplus rice is kept until needed for consumption or trade. The irrigated rice cycle is divided into eleven named phases, each associated with specific work activities and accompanied by ritual and ceremonial observances, including a community-wide harvest celebration.

In small gardens near their homes Dusun cultivate about 25 types of food crops. These include sweet potato, greater yam, manioc, bottle gourd, various kinds of beans, squashes, chilies, and many other garden plants. Garden borders are used to grow trees and shrubs producing coconuts, bananas, breadfruit, mangoes, papayas, durians, limes, and other fruits that supplement the daily rice diet. Six plants are commonly cultivated near houses or garden plots for the manufacture of tools, shelter, and clothing, including bamboo, kapok, betel palm, indigo, and derris. Bamboo shoots are also consumed as food.

A range of domestic animals provides food, labor, and raw materials. Chickens and ducks are common, and geese are sometimes kept. Pigs and water buffalo are raised for food, with buffalo also serving as a primary source of power in rice cultivation. Both pigs and buffalo play important roles in ritual activities central to Dusun life. Dogs and cats are kept in most households, with dogs assisting in hunting and cats helping to control rats in houses and rice storage structures.

Traditionally, Dusun economic life has combined household production, specialized crafts, and market exchange. Part-time and seasonal male and female specialists make and repair agricultural, hunting, and foraging tools, produce buffalo harnesses and plows, and weave rattan traps and bamboo baskets, while metal tools, ceramics, and cloth were traditionally obtained through Chinese trade. For centuries the Dusun have depended on traders for manufactured goods, supplemented by weekly markets in which women sell or barter local produce and purchase manufactured items, making these markets key economic and social centers.

Dusun Activism

In 2010, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Adrian Lasimbang, 33, belongs to the Kadazan tribe of Sabah State, Malaysia, located in the north of Borneo Island. In 2010 he joined the COP10 conference as a representative of the Indigenous Peoples Network of Malaysia. In Sabah, vast swaths of tropical forests have been destroyed to make way for oil palm plantations. Oil palms are used to make detergents and biofuel. The number of oil palm plantations in Sabah has increased sixfold in the past 20 years. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 20, 2010]

On Borneo, any number of plans to construct aluminum factories have been launched since Asia's biggest hydroelectric dam was constructed on the island. Producing aluminum requires huge amounts of energy. But the aluminum produced by such factories and the detergents made from oil palms are consumed by people in developed countries, Lasimbang said. He wants advanced countries to realize the extent to which nature in developing nations is damaged as a result of their consumerism, and reconsider their practices.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026