DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE

The Dutch established a monopoly on the spice trade from the Moluccas . They gained control over the clove trade through an alliance with the sultan of Ternate in the Moluccas in 1607. Dutch occupation of the Bandas from 1609 to 1623 gave them control of the nutmeg trade. Dutch control of the region was fully realized when Melaku was captured from the Portuguese in 1641.

On the Banda Islands, the Dutch tried to trade knives, woolen clothes and other things that the Banda islander didn’t need. The Dutch demanded that they be given a monopoly and found a few complaint chiefs that signed “contracts” promising them their desired monopoly. In the meantime the English had arrived in the area and they and the Dutch tried to outmaneuver one another for control of the islands.

The Dutch could be quite ruthless when it suited their purposes. In the Bandas, one governor-general beheaded and quartered 44 local chiefs and displayed the remains in 1621 at a fort after Dutch “negotiators” were killed in a dispute over the placement of a fort on sacred site. See Jan Pieterszoon Coen Below.

In what today is eastern Indonesia, the VOC with the help of indigenous allies fundamentally altered the terms of the traditional spice trade between 1610 and 1680 by forcibly limiting the number of nutmeg and clove trees, ruthlessly controlling the populations that grew and prepared the spices for the market, and aggressively using treaties and military means to establish VOC hegemony in the trade. One result of these policies, exacerbated by the late-seventeenth-century fall in the global demand for spices, was an overall decline in regional trade, an economic weakening that affected the VOC itself as well as indigenous states, and in many areas occasioned a withdrawal from commercial activity. [Source: Library of Congress]

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOLUCCAS: GEOGRAPHY, ISLANDS, WILDLIFE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

SPICES AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com;

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: HISTORY, IDENTITY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: LIFE, SOCIETY, FAMILY, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

MALUKA (CENTRAL MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH EMPIRE: WEALTH, EXPLORATION AND HOW IT WAS CREATED factsanddetails.com

END OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY, BRITAIN IN INDONESIA AND THE JAVA WAR factsanddetails.com

NETHERLANDS INDIES EMPIRE IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDIANS, CHINESE AND ARABS IN INDONESIA: IBN BATTUTA, YIJING, ZHENG HE factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PORTUGAL AND THE AGE OF DISCOVERY factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE TRADE EMPIRE IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

Dutch Ships and Sea Routes to Indonesia

The Dutch developed quicker and more efficient southern routes between the South Africa and Indonesia that were more efficient and profitable than ones used by the Portuguese, who followed slower, seasonal coastal routes via India, and the Spanish, who wet the long way around via the Pacific and Mexico.

Holland was the world's leader in map making. The VOC hired the best mapmakers in the Netherlands to make "secret atlases" for their exclusive use. The company possessed 180 maps and charts that showed the best routes around Africa to India, China, Japan and the East Indies. The owners of the company denied the existence of the maps which were not made public until some of them were mistakenly found their into the library of Austrian aristocrat.

In the 17th century oak forests in Poland were cleared to supply wood for Dutch ships used in voyages to the East Indies, About 4,000 planks were needed for each, which lasted only one or two voyages before the wood rotted and the ship fell apart.

The Flying Dutchman was Dutch East Indies ship destroyed by a fierce storm near the Cape of Good Hope in 1680. A ghost version of ship has reportedly been seen several times. In March, 1939, for example, about 60 people on Glencairn beach in South Africa reportedly saw a 17th century ship sail towards a sandbar and then disappear. The Flying Dutchman was immortalized by a Wagner opera.

Dutch United East India Company (VOC) in the Moluccas

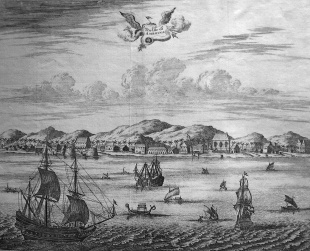

In 1599 Dutch ships reached the Moluccas for the first time. Presenting themselves as enemies of the Portuguese, the Dutch were warmly received by Portugal’s local opponents, who were all Muslims. The Bandanese, the Hituese, and the Ternatans concluded agreements with the newcomers, promising to sell their spices to the Dutch at favorable prices, while the Dutch pledged support against the Portuguese. A lasting Dutch presence, however, was only secured after the establishment of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC, or Dutch East India Company) in 1602. By 1605 the VOC had captured the Portuguese forts in Ambon and Tidore, effectively ending Portuguese power in the Moluccas. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The VOC functioned simultaneously as a commercial enterprise and a military authority. In Asia it was empowered to conclude treaties, build fortifications, and administer territories on behalf of the Dutch Republic. The company soon recognized the exceptional opportunities offered by the Moluccas. These islands were the sole producers of cloves, nutmeg, and mace, and they covered a relatively small area with a limited population—no more than about 100,000 people in the key spice-producing regions. This combination made the islands relatively easy to control. The VOC envisaged forcing the local population to produce spices exclusively for the company, thereby establishing a monopoly over their sale in Asian and European markets.

VOC Spice Monopoly in the Moluccas

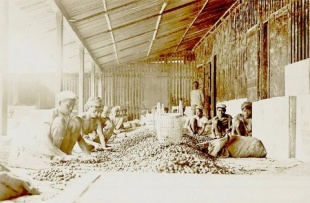

Dutch factory in Ambon in the Spice Islands in the early to mid-17th century; the island was the scene of the infamous Amboyna Massacre of 1623 that put an abrupt end to the spice trade ambitions of the English East India Company in the Malay Archipelago

The VOC established a spice monopoly in the Moluccas that yielded enormous profits. As the sole buyer, the VOC could keep purchase prices low, while as the sole supplier it could impose high prices internationally. Preventing smuggling was essential to maintaining this system. The monopoly required the closure of the Moluccas to all free trade, and the VOC strictly forbade its employees from engaging in private spice trading. Within roughly fifty years, this policy was largely realized.

The Dutch kept the nutmeg trade centered in the Moluccas. For a time nutmeg was the most valuable commodity in the world after gold and silver. In the early 17th century ten pounds of nutmeg could be purchased for less than an English penny in the Banda Islanda and resold in Europe for over two pounds, a mark up of over 60,000 percent. In addition to a being a flavoring nutmeg was valued as a preservative and medicine and was said to ward off the plague.

The Dutch went through great lengths to preserve their monopoly. During the Spice Wars of the 17th and 18th century the Dutch uprooted groves of nutmeg and cloves trees to keep prices high and cut their competitors out of the market. Dutch settlers were given slaves to run their plantations but were told they could not return home to Holland and were required to produce cloves exclusively for the VOC at fixed prices. Seventy large plantations were established mostly on Banda and Ai islands.

Jan Pieterszoon Coen and Ruthless Dutch Policies to Control the Spice Trade

The most influential and dynamic Dutch ruler in the early years of Dutch control of Indonesia was Jan Pieterszoon Coen, the governor general of the VOC from 1619 to 1623 and again from 1627 to 1629. Among other things he nearly wiped out the entire native population of the Banda Islands in Moluccas to keep the spice trade secret and under control; and aimed to make Jakarta into the main trading port of Asia. The latter was never realized but he is credited with instituting policies that enabled the Dutch to establish their monopoly in the spice trade in Indonesia.

Coen seized the port of Jayakarta (modern Jakarta) from the sultan of Banten in western Java and established the trading post at Sunda Kelapa. Since then, it has served as the capital of the VOC, of the Netherlands Indies after 1816, and of the independent Indonesian state after World War II. Coen also developed a plan to create spice plantations using Burmese, Madagascan and Chinese labourers. Although this plan was not realized in his lifetime it too became an important aspect of the Dutch occupation of Indonesia later on.

Coen was determined to go to almost any lengths to establish and reserve a VOC monopoly of the spice trade. He accomplished his goal by both controlling output and keeping non-VOC traders out of the islands. Ambon had been seized from the Portuguese in 1605, and anti-Iberian alliances were made with several local rulers. However, the English East India Company, established in 1600, proved to be a tenacious competitor. When the people of the small Banda archipelago south of the Malukus continued to sell nutmeg and mace to English merchants, the Dutch killed or deported virtually the entire population and repopulated the islands with VOC indentured servants and slaves who worked in the nutmeg groves.

Similar policies were used by Coen's successors against the inhabitants of the clove-rich Hoamoal Peninsula on the island of Ceram in 1656. The Spanish were forced out of Tidore and Ternate in 1663. The Makassarese sultan of Gowa in southern Sulawesi, a troublesome practitioner of free trade, was overthrown with the aid of a neighboring ruler in 1669. The Dutch built fortresses on the site of the Gowa capital of Makassar (modern Ujungpandang) and at Manado in northern Sulawesi and expelled all foreign merchants. In 1659 the Dutch burned the port city of Palembang on Sumatra, ancient site of the Srivijaya empire, in order to secure control of the pepper trade. *

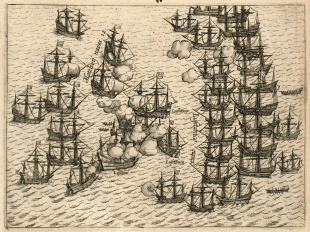

Challenges to the VOC in the Moluccas by Britain and Spain

Initially, Spain attempted to counter Dutch expansion. In 1605 Spanish forces advanced from Manila, allied with Tidore, occupied the former Portuguese fortress on the west coast of Ternate, and established a garrison in Tidore. To defend themselves and their Ternatan allies, the Dutch built a fortress on the east coast of Ternate in 1607. Although the Dutch and Ternatans failed to expel the Spaniards from Tidore or from western and southern Ternate, they succeeded in making Spanish occupation prohibitively costly. As a result, Spain withdrew voluntarily from the Moluccas in 1663. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The English also challenged Dutch ambitions. English ships appeared in the Moluccas from 1604 onward, but in 1623 the VOC employed its full military strength to eliminate the English presence entirely.

The most serious resistance to the VOC monopoly came from the Moluccans themselves. Nowhere was Dutch policy more ruthless than in the Banda Islands. Because the Bandanese continued to sell nutmeg and mace to anyone offering higher prices, the VOC launched a military campaign in 1621 that crushed all resistance. Survivors were deported as slaves to Batavia, while only a few escaped to distant islands. The conquered lands were divided into hereditary estates granted to Dutch settlers, who worked them with slave labor. Until the nineteenth century these tenants were required to deliver nutmeg and mace to the VOC at fixed prices.

Spice Wars, Pulau Run and Manhattan

The Dutch exterminated natives unwilling to cooperate with them and burned piles of nutmeg after bumper harvests to keep prices high. They also soaked nutmeg seeds in lime so no one could plant them without their authorization. This plan was thwarted when fruit pigeons carried nutmeg seeds to other islands. To keep their monopoly intact the Dutch sent out teams to track down and destroy every last plant.

As part of the solution to the “spice war” the 1667 Treaty of Breda was signed in which the English dropped their claim to the Bandas, where nutmeg was grown. As part of the deal the English exchanged Pulau Run, a tiny islet in the Spice Islands, for Manhattan (then known as New Amsterdam), which the Dutch had famously obtained by trading $24 worth of beads and trinkets in 1627.

Diane Selkirk of the BBC wrote: With the local population subdued and enslaved as workers, the VOC monopoly of the spice trade was now hampered by just one thing. In 1616, the English had managed to gain control of a Banda Island called Run; a speck of island less than 2 miles long and just more than half a mile wide. It was here the English claimed their first colony and formed the English East India Company, and in doing so launched the British Empire. [Source: Diane Selkirk, BBC, October 12, 2017]

The English East India Company was only able to defend Run against the Dutch for four years – but they didn’t give up their claim. In 1664, in retaliation, four English frigates were sent across the Atlantic Ocean to seize a Dutch holding called New Amsterdam. The seat of the colonial Dutch government at southern tip of Manhattan Island had a population of 2,000 people, but they quickly capitulated. In 1677, the two countries came to an agreement; both had refused to give up their claims on each other’s islands, so they made a trade. The Dutch gained control of Run and the English got New Amsterdam – a new colony they renamed New York.

VOC Rule in the Moluccas Becomes More Authoritarian

The violence in Banda sent shockwaves throughout the Moluccas, demonstrating that the VOC was prepared to use extreme measures to protect its interests. Thereafter, though not without difficulty, the Dutch imposed their authority in Ternate and Ambon. Having eliminated both open and covert resistance and excluded Asian traders from the region, the VOC concluded treaties between 1652 and 1657 with the rulers of the North Moluccas. These agreements acknowledged VOC supremacy and bound the rulers to sever relations with other powers, exclude foreigners, deny refuge to VOC enemies, refrain from trading in or cultivating spices, assist in locating spice trees, supply goods and labor to the company, and accept the construction of VOC fortifications wherever deemed necessary. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

At the same time, the inhabitants of Ambon and three nearby islands were compelled to cultivate cloves in quantities fixed by the VOC and to sell them at predetermined prices. A tightly supervised cultivation system was thus introduced, designed to supply the entire global clove market. Village chiefs played a central role in enforcing this system and were rewarded with a commission amounting to 10 percent of the payments made to producers under their authority. They were also responsible for ensuring that villagers performed compulsory services for the VOC, which imposed heavy burdens on the population.

When the VOC took over from the Portuguese in Ambon in 1605, it inherited a community of indigenous Christians. Formerly allied with the Portuguese, they now became subjects of the Dutch and were required to grow cloves and perform corvée labor like their Muslim neighbors. They received only minimal education and pastoral care.

In the North Moluccas, the VOC’s main objective after 1657 was to isolate Ternate, Tidore, and Bacan from external contacts. European settlements evolved from trading centers into guard posts designed to prevent the cultivation and smuggling of cloves. Within this system of indirect rule, however, Dutch control over Tidore remained weak because no permanent garrison was established there. Although nominally subject to the VOC, Tidore and its dependencies largely escaped effective Dutch supervision.

Decline of the Dutch Spice Monopoly

By the late eighteenth century, the VOC’s power was clearly declining. The company faced growing problems, including piracy and the rise of Prince Nuku of Tidore, who had been passed over for succession in 1779. Nuku fled to areas east of Halmahera, where he gathered widespread support and, with the help of British private traders from India, engaged in spice smuggling. In 1797 he succeeded in capturing Tidore with his fleet, aided by two English ships. In the meantime, the Dutch–English War of 1780, broke the VOC’s spice-trade monopoly with the Treaty of Paris, which permitted free trade in the East.

The Dutch maintained their monopoly on the nutmeg trade for two and half centuries, until the late 18th century when a French missionary smuggled nutmeg seedlings out of the Dutch East Indies and they were replanted in Madagascar, Mauritius and Zanzibar. With is move the Dutch spice monopoly was broken and the Moluccans were largely forgotten.

Brief British Control of the Moluccas

Soon after the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789, Britain and France became locked in a series of conflicts known collectively as the Napoleonic Wars (1793–1802, 1803–1814). The Netherlands was drawn into France’s orbit as a satellite state, a development that carried serious consequences for its Asian possessions. In 1796 the British occupied Ambon and Banda, and in 1801, with the support of Nuku of Tidore, they also took control of Ternate.

The British took over the Moluccas for 12 years to counter the annexation of Holland by Napoleon Under British rule, compulsory cultivation and delivery of spices were retained, but the administration simultaneously transplanted young clove and nutmeg trees to other British colonies. Over time, this policy ensured that the Moluccas would lose their unique status as the world’s sole source of cloves, nutmeg, and mace.

In 1803 the Moluccas were returned to Dutch control. What followed was a period of severe hardship, as the islands were placed on a wartime footing in anticipation of renewed British attacks. The population was subjected to heavier demands than ever before, further worsening living conditions.

In 1810 Ambon, Banda, and Ternate once again fell into British hands. After the privations of the preceding years, this second British interregnum (1810–1817) came as a relief to the Moluccan population. The British resident, William Byam Martin (1811–1817), showed genuine concern for local welfare and was notably reluctant to rely on coercion. Although the spice monopoly was preserved, its harsher features were eliminated. In nearly every respect, Moluccans found British administration preferable to Dutch rule.

Collapse of the Dutch Spice Trade

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, the Moluccas were returned to the Dutch in 1817. Disillusionment with the restoration of Dutch authority soon led to rebellion in the Ambon Islands, and it took the Dutch six months to suppress the uprising.Under the new colonial administration, direct involvement in production and trade was no longer the primary concern. As the nineteenth century progressed, emphasis shifted toward orderly governance intended to facilitate private trade and commercial development.

During the 12 years that the British controlled the Moluccas at the turn of the 19th century they spread the cultivation of nutmeg to the Caribbean. By the time the Dutch reclaimed Indonesia in return for letting the British have Malaysia the damage had been done. By this time nutmeg had lost its luster anyway as its health benefits were questioned and refrigeration reduced demand for it as a preservative. Cultivation in Grenada in the Caribbean became so big the island designed its flag with the green, yellow and red colors of the nutmeg seed and placed am image of a nutmeg seed on one side. Today, nutmeg production has dropped in the Bandas to the point there are worries it might disappear.

The restoration of Dutch rule in 1917 did not mean a simple return to the conditions of the VOC era. By this time, the Dutch monopoly over the global supply of cloves, nutmeg, and mace had completely collapsed, a development with far-reaching consequences for the Moluccas. Although compulsory spice cultivation initially continued, enforcement of the ban on clove cultivation outside Ambon effectively ceased. As production of cloves, nutmeg, and mace expanded beyond the Moluccas, world market prices declined. Consequently, the Dutch government began to incur losses on the spices it was required to purchase in Ambon and Banda, and on January 1, 1864, the monopoly on clove and nutmeg production was officially abolished. During the nineteenth century, as Moluccan spices lost their former value, the region increasingly came to be regarded as economically unattractive. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2025