FIRST INDIANS TO REACH INDONESIA

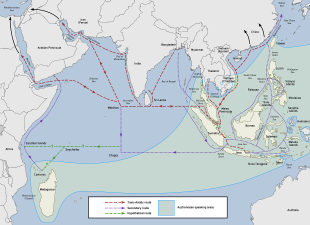

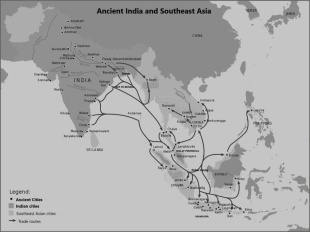

Indonesia’s maritime passages brought traders from India, Arabia, Persia, China, and mainland Southeast Asia in prehistoric times. The earliest Indians to reach Indonesia were not individual adventurers but waves of traders, sailors, priests, and scholars who crossed the Indian Ocean centuries before the Common Era. Many of these early travelers came from India’s eastern coastal regions, particularly Kalinga (modern Odisha) and Vengi in Andhra Pradesh. Archaeological discoveries, including South Indian rouletted pottery in Bali dating to around 660 B.C. point to a well-established Indian presence long before the appearance of formally documented rulers. These early contacts helped lay the foundations for trade networks and facilitated the spread of Hinduism and Buddhism throughout the archipelago.

Over the centuries, Indian maritime influence grew steadily. Inscriptions and historical records refer to “Klings” from Kalinga as well as traders from places such as Aryapura (Ayyavole) and Pandikira in Karnataka by the 9th century CE, demonstrating the broad geographical origins of Indian communities active in Southeast Asian commerce. These traders not only exchanged goods but also introduced religious texts, rituals, and philosophical ideas that would shape Indonesian culture for more than a millennium. Their efforts played a crucial role in the rise of major Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms, including Srivijaya and Majapahit.

A significant expansion of Indian activity came later from South India. After the Chola Empire’s attack on Srivijaya in A.D. 1024, Tamil traders intensified their presence across the region, strengthening commercial routes and establishing deeper ties with local societies. Throughout this long history, no single “first traveler” can be identified; rather, the Indian influence in Indonesia emerged from a continuous flow of people engaged in trade, scholarship, and religious exchange from deep antiquity onward.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS FIRST ARRIVED: SPICES, POWERFUL STATES, DEALS, ISLAM factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PORTUGAL AND THE AGE OF DISCOVERY factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE TRADE EMPIRE IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH EMPIRE: WEALTH, EXPLORATION AND HOW IT WAS CREATED factsanddetails.com

DUTCH, THE SPICE TRADE AND THE WEALTH GENERATED FROM IT factsanddetails.com

END OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY, BRITAIN IN INDONESIA AND THE JAVA WAR factsanddetails.com

NETHERLANDS INDIES EMPIRE IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER DUTCH RULE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

MATA HARI factsanddetails.com

Earliest Chinese Travelers in Indonesia

The earliest Chinese travelers to the Indonesian archipelago were likely merchants of the Han Dynasty, active as early as the 2nd century AD. Ancient Chinese sources describe traders navigating Southeast Asian maritime routes to exchange silk, ceramics, and other goods with emerging kingdoms such as Srivijaya. One of the most significant early visitors was the Buddhist monk Yijing (I-Tsing), who stopped in Srivijaya in 671 AD for six months to study and collect sacred texts—evidence of the region’s importance as a center of Buddhist learning and a vital waypoint for Chinese pilgrims en route to India.

During the Tang and Song Dynasties, Chinese maritime activity increased, and traders continued to travel throughout the archipelago. Some chose to settle permanently, forming early Chinese communities in port cities such as Palembang and Semarang. These settlements grew slowly at first but laid the foundation for larger migration waves that began in the 13th century and expanded in later centuries, eventually leading to substantial Chinese populations in major ports including what is now Jakarta.

Zhao Rukuo, a Song Dynasty official and author of the 13th-century trade compendium Zhu Fan Zhi (Records of Foreign Peoples), described "Sanfoqi" (often identified as Srivijaya) as a powerful maritime kingdom in Southeast Asia, known for its vast trade, tribute to China, control of sea routes, rich products like camphor and ivory, and a significant Buddhist presence, though modern scholarship debates whether "Sanfoqi" always meant Srivijaya or sometimes Cambodia (Angkor). [Source: Google AI]

Interactions intensified in the medieval period. In 1293, Kublai Khan of the Yuan Dynasty launched a major naval expedition to Java, an operation that ultimately ended in failure but demonstrated the extent of Chinese engagement with Southeast Asian powers. By this time, Chinese traders and laborers were arriving in greater numbers, integrating into local society while also contributing to the region’s expanding commercial networks. Over time, their communities became influential social and economic forces within Indonesia’s port cities.

Yijing

The Sumatra-based Srivjaya state was a Buddhist kingdom that thrived from the 8th to 13th centuries.. As a stronghold of Mahayana Buddhism, Srivijaya attracted pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. These included the Chinese monk and pilgrim Yijing and the eleventh-century Buddhist scholar Atisha, who played a major role in the development of Tibetan Buddhism. [Sources: Library of Congress, noelbynature, southeastasianarchaeology.com, June 7, 2007]

Yijing (635–713) briefly visited Srivijaya in 671 and 687 and then lived there from 687 to 695, recommending it as a world-class center of Buddhist studies. Yijing travelled between China and India to copy sacred texts mentioned the high quality of Sanskrit education at the Srivijayan capital of Palembang, and recommended that anyone who wanted to go to the university at Nalanda (north India) should stay in Palembang for a year or two to learn “how to behave properly”. Asia. In 671, Yijing reported that around 1,000 monks from various countries were studying Buddhism—particularly Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions—in Palembang.

Yijing wrote in “A Record of Buddhist Practices Sent Home from the Southern Sea”: "Many kings and chieftains in the islands of the Southern Ocean admire and believe (Buddhism), and their hearts are set on accumulating good actions. In the fortified city of Bhoga [Palembang] Buddhist priests number more than 1,000, whose minds are bent on learning and good practices. They investigate and study all the subjects that exist just as in the Middle Kingdom (Madhya-desa, India); the rules and ceremonies are not at all different. If a Chinese priest wishes to go to the West in order to hear (lectures) and read (the original), he had better stay here one or two years and practise the proper rules and then proceed to Central India."

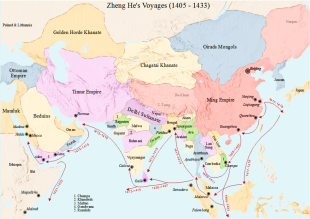

Zheng He

The great Chinese eunuch-explorer Zheng He visited Indonesia in the early 15th century. His memory has been kept alive there in several ways. His expedition led to wave of Chinese emigration to southeast Asia. In some places in Indonesia he is regarded as a deity and temples have been launched to honor him.

Zheng He (also known as Chêng Ho, Cheng Ho, Zheng Ho, and the Three-Jewel Eunuch) is a Chinese navigator without a penis or a set of testicles whose achievements as an explorer rank with those of Columbus and Magellan but who has been largely forgotten because his travels had little impact on history. [Source: Frank Viviano, National Geographic, July 2005]

Zheng He (pronounced “jung huh”) embarked from China with a huge fleet of ships and journeyed as far west as Africa, through what the Chinese called the Western seas, in 1433, sixty years before Columbus sailed to America and Vasco de Gama sailed around Africa to get to Asia. Zheng also explored India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and Arabia with about 75 times as many ships and men as Columbus took with him on his trans-Atlantic journey.

Zheng He was very tall and a man of incredible ambition. Some descriptions say he stood seven feet tall, possessed a waist that was five feet in circumference and had “a voice as loud as a huge bell." He was a devout Muslim and supposedly earned his nickname “Three Jewel Eunuch” for the gems he gave out as gifts. His lack of recognition as a great explorer is partly because the Chinese never went to any length to declare he was a great explorer.

Related Articles: ZHENG HE: THE GREAT CHINESE EUNUCH EXPLORER ioa.factsanddetails.com ZHENG HE'S EXPEDITIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Zheng He's Expeditions

Sponsored by the Yongle Emperor to show the world the splendor of the Chinese empire, the seven expeditions led by Zheng He between 1405 and 1433 were by far the largest martime expeditions the world had ever seen, and would see for the next five centuries. Not until World War I did there appear anything comparable.

The largest expedition utilized a crew of 30,000 men and a fleet of 317 ships, including a 444-foot-long teak-wood treasury ship with nine masts, the largest wooden ship ever made; 370-foot, eight-masted “galloping horse ships,” the fastest boats in the fleet; 280-foot supply ships; 240-foot troop transports; 180-foot battle junks, a billet ship, patrol boats and 20 tankers to carry fresh water. The expedition was nothing less than a floating city that stretched across several kilometers of sea. By contrast to Columbus' expedition consisted for three ships with 90 men. The largest ship was 85 feet long. The largest ships in Vasco de Gama's fleet had four masts and were about 100 feet long.

The crew included sailors and mariners, seven grand eunuchs, hundreds of Ming officials, 180 physicians, geomacers, sail makers, blacksmiths, carpenters, tailors, cooks, merchants, accountants, interpreters that spoke Arabic and other languages, astrologers that predicted the weather, astronomers that studied the stars, pharmacologists that collected plants, ship repair specialists, and even protocol specialist that were responsible for organizing official receptions. To guide the massive ships, Chinese navigators used compasses and elaborate navigational charts with detailed compass bearings.

Zheng He’s Adventures in Indonesia and Southeast Asia

In 1407, Zheng He” ships encountered the notorious Cantonese pirate Chen Zuyo in the Strait of Malacca. Operating out of Sumatra, Chen used his fleet of armed junks to control the straits. Almost all ships that passed through were either raided or forced to pay tribute. When Zheng arrived he demanded the pirate’s surrender. Chen agreed while secretly planning a surprise attack. Zheng had been alerted to the details of his plan and was ready. In the fierce battle Chen was captured, 5,000 of his men were killed and his fleet was destroyed. Chen was publically executed in Nanjing. The Chinese informant who gave up Chen was made the ruler of Palembang.

Ma Huan wrote about sampling jack fruit with “morsels of yellow flesh, as big as hen’s eggs and tasting like honey” in Vietnam; discovering the “ten different uses” of the coconut in India;and seeing cockatoos, mynahs and parrots—“all of which can imitate human speech”--- in Java. In Java he noted that “little boys of three years to old men of hundred years” carried knives. “If a man touches their head with his hand, or if there is a misunderstanding about money at a sale, or a battle of words when they are crazy with drunkenness, they at once pull out their knives and stab [each other].”

Early Arabs and Persians in Indonesia

Chinese records from A.D. 674 mention an Arab dignitary heading a settlement on West Sumatra's coast, indicating early presence. Early Arab and Persian travelers—mainly Muslim traders from southern Arabia and the Persian Gulf—began arriving in Indonesia as early as the 8th century, drawn by the flourishing spice trade in nutmeg and cloves. Their voyages linked the archipelago to Middle Eastern and European markets through major trade corridors such as the Malacca Strait. Over the centuries, many of these merchants established settlements, intermarried with local communities, and became part of Indonesia’s cultural landscape.

Their arrival was driven first and foremost by commerce. Indonesia’s spices were among the most coveted commodities of the ancient world, and traders followed well-established sea lanes that connected the Middle East to India, Southeast Asia, and China. Although contact between Indonesians and the Middle East existed before Islam, more substantial Arab settlement coincided with the rise of Islam. Traders not only carried goods but also introduced the new faith, often acting as informal missionaries.

Cultural exchange played a central role in the spread of Islam. Merchants brought religious ideas—including Sufi traditions—along with their trading activities. As they integrated into local society through marriage and settlement, Islamic teachings blended with indigenous customs, gradually shaping local religious and cultural practices. Key emporiums in the Middle East, such as Hormuz and Muscat, served as vital hubs linking these traders to Indonesian ports like Malacca.

The early arrivals included merchants from Yemen, Oman, and Persia, while later waves brought Hadhrami Arabs from Hadhramaut, many of whom settled in cities such as Surabaya. Through peaceful trade, diplomacy, and cultural interaction—rather than conquest—these groups helped spread Islam across the archipelago and firmly integrated Indonesia into the wider Indian Ocean trading world.

Ibn Battuta

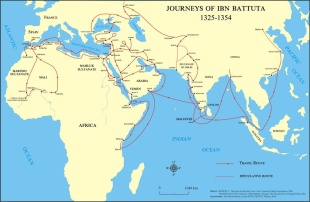

The Arab traveler Muhammad ibn-'Abdullah ibn-Battuta visited the Islamic town of Perlak in Sumatra in 1345-46 and wrote that its monarch was a Sunni rather than a Shia Muslim. Marco Polo visited the same town in 1292.

Ibn Battuta (1304-1369) is regarded as the greatest traveler of all time. He was an Islamic scholar from Tangier in present-day Morocco who traveled 120,000 kilometers (75,000 miles) through more than 40 present-day countries Africa, the Middle East and Asia during a 27 year period 700 years before trains and automobiles. He described his adventures in “Travels in Asia and Africa”. Ibn Battuta was a contemporary of Marco Polo (1254-1324). His journeys preceded those of Columbus by about 150 years. Although he is little known in the West he is as well known as Marco Polo and Columbus in the Arab world.

Ibn Battuta was born in Tangiers, Morocco. His full name was Sheikh Abu Abdallah Muhammed ibn Abdallah ibn Muhammed inb Ibrahim al-Lawati. He had the education of typical affluent Muslim child. He is believed to have memorized the Koran by the age of 12. Ibn Battuta has been honored in his hometown with the Hotel Ibn Battuta, the Ibn Battuta ferry to Spain and the Ibn Battuta Café, which offers an Ibn Battuta hamburger.

Book: “Travels with a Tangerine: A Journey in the Footnotes of Ibn Battutah” by Tim Mackintosh-Smith (Welcome Rain Publishers, 2001). Battuta’s journal is available in Arabic under the title “The Precious Gift of Lookers Into the Marvels of Cities and Wonders of Travel”.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: IBN BATTUTA: HIS LIFE, JOURNEY AND WRITINGS factsanddetails.com; IBN BATTUTA ON THE MARITIME SILK ROAD BETWEEN INDIA AND CHINA factsanddetails.com

Ibn Battuta in Indonesia and China

Ibn Battuta travel to Sumatra in present-day Aceh around 1345, staying at the Samudra Pasai Sultanate, the easternmost Islamic territory he encountered, where he met its pious Sultan, Al-Malik Al-Zahir. He stayed as a guest of the Sultan for about two weeks, receiving supplies and a ship for his voyage to China. Ibn Battuta described Samudra Pasai as the furthest point of the Islamic world at that time. He noted the ruler's deep piety, his practice of the Shafi'i school of Islamic law, and the Sultan's zeal for fighting non-Muslims.

Near Sumatra, Ibn Battuta's ship was plunder by pirates. Earlier another ship was shipwrecked in the Indian Ocean. He arrived in Sumatra in present-day Aceh. By some estimates Islam had only arrived about a a half century earlier in Sumatra. The ruler there, Malik al-Zahir, Ibn Battuta wrote is a "humble-hearted man who walks on foot to the Friday prayer. His subjects...take a pleasure in warring for the Faith...They have the upper hand over all the infidels in their vicinity."

Ibn Battuta wrote that he visited "Muljawa" and the port of "Tawalisi," neither of whom have been found. In Tawalisi he wrote he met an Amazon princess who lead an army of slave girl warriors "who fight like men." She gave him lemons, rice, peppers, and two buffalos.

Ibn Battuta made it as far east as China In 1344, Ibn Battuta arrived at Quanzhou in China, just across a strait from Taiwan. The port here he wrote was "one of the largest. I saw in it about a hundred large junks." Later he traveled to Guangzhou (Canton). Ibn Battuta was amazed by China. He wrote: "China is the safest and best regulated of countries for a traveler. A man may go by himself on a nine-month journey, carrying with him large sums of money, without any fear...Silk is used for clothing even by poor monks and beggars." Porcelain is "the finest of all makes of pottery...The hens in China are...bigger than the geese in our country.” Ibn Battuta was also shocked by what he saw in China. "The Chinese themselves are infidels, who worship idols and burn their dead like the Hindus...eat the flesh of swine and dogs, and sell it in their markets." Ibn Battuta returned home via Indonesia, India, the Persian Gulf, Arabia, Egypt and the Mediterranean.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025