DUTCH EMPIRE

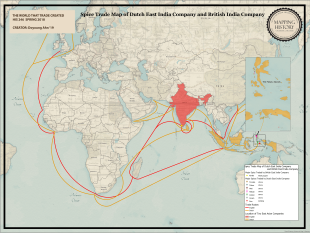

The United Provinces of the Netherlands (the government in control of Holland in the early 17th century) was, in a sense, the world's first modern state. It was a republic dominated by middle class burghers rather than a dynastic monarchy. In the first half of the 17th century, the United Provinces grew in power and wealth. They possessed the largest merchant fleet in the world and over time opened up new trade began and acquired colonies. At one point the Dutch controlled half the world's shipping

The Dutch had been traders a long time. Winning independence from Spain in 1581, the Netherlands became a major seafaring power. During the seventeenth century, Amsterdam emerged as Europe's primary center for commerce and banking. Largely Protestant and Calvinist, the new state, unlike Portugal, did not reflect the crusading values of the European Middle Ages. The Bank of Amsterdam was founded in 1609, 85 years before the Bank of England. Some say the Dutch East India Company was the first multinational corporation.

After Spain absorbed Portugal in 1580 the Dutch seized Portuguese possessions and created a vast, though short-lived commercial empire in Brazil, the Antilles, Africa, India, Ceylon, Malacca, Indonesia and Taiwan and challenged Portuguese traders in China and Japan. Naval and land battle between colonial powers in Southeast Asia in the 17th century gave the English and the Dutch access to the lucrative spice trade route the Portuguese had established. The Dutch empire was cobbled together and comprised mainly of far flung islands that were often as different from one another as individual nations and often had little to do each with each other than occasional trade.

In the 17th century, Holland controlled an empire that embraced three of the four main continents and held sway over 80 million people. Despite this the Dutch were quite skilled at avoiding trouble. They were usually not involved in the wars that besieged France, Spain and England. During the Golden Age of Netherlands trade wealth poured in from Dutch territories in Sri Lanka, India and Indonesia.

Naval and land battles between colonial powers in Southeast Asia in the 17th century gave the English and the Dutch East India Company access to the lucrative spice trade route the Portuguese had established. The Dutch in some cases moved in and took possession of many of the Portuguese forts by force. which in turn were taken away from them by the English. The Spanish and Portuguese were able to establish their large empires in Asia because they encountered virtually no resistance. The Sultans in Malaysia and Indonesia were easy to overcome, Filipinos were just tribal farmers, and the Mughals in India didn't have much of a navy. The Portuguese and Spanish established themselves by building forts and trading out of them.

RELATED ARTICLES:

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH, THE SPICE TRADE AND THE WEALTH GENERATED FROM IT factsanddetails.com

END OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY, BRITAIN IN INDONESIA AND THE JAVA WAR factsanddetails.com

NETHERLANDS INDIES EMPIRE IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER DUTCH RULE IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

RISE OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM IN THE EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

MATA HARI factsanddetails.com

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS FIRST ARRIVED: SPICES, POWERFUL STATES, DEALS, ISLAM factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDIANS, CHINESE AND ARABS IN INDONESIA: IBN BATTUTA, YIJING, ZHENG HE factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PORTUGAL AND THE AGE OF DISCOVERY factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE TRADE EMPIRE IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

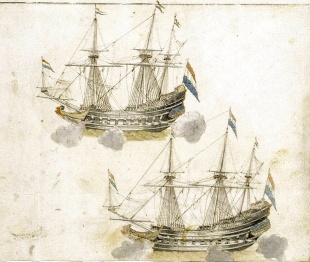

Dutch Ships in the the Age of Exploration

Dutch ships of the Age of Exploration—especially during the 17th-century Golden Age—were revolutionary in design and efficiency. Their fleets were dominated by the fluyt, a merchant vessel engineered for maximum cargo capacity with a minimal crew, alongside the large and heavily armed East Indiamen used for long-distance VOC voyages to Asia. The Dutch also produced agile smaller vessels such as jachts, as well as sturdy warships including galleons and, later, ships of the line. Together, these innovations allowed the Dutch Republic to dominate global trade and naval power during the period.

Among these vessels, the fluyt (or fluitschip) was a true game-changer. Its wide, rounded hull provided enormous cargo space, while the narrow deck reduced taxation in ports where fees were based on deck area. The ship required significantly fewer sailors than comparable vessels, making it extremely economical to operate. For longer and more dangerous voyages, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) relied on its heavily armed East Indiamen—large, multi-decked ships capable of carrying both valuable goods and substantial cannon. Smaller vessels such as the jacht or pinas were prized for their speed and maneuverability and were used for exploration, coastal patrol, and pursuit.

Dutch shipbuilding owed its success to remarkable technological and organizational innovations. Shipyards pioneered early assembly-line methods, using standardized components and windmill-powered sawmills to accelerate production. As a result, vessels could be built in a matter of weeks. Designs focused on efficiency: the fluyt minimized labor costs and maximized cargo volume, while other ship types balanced speed, durability, and firepower. Most were constructed from strong oak and built using either carvel-planked or clinker-built techniques, depending on function.

These advancements enabled the Dutch to produce thousands of ships, fueling the expansion of the VOC and other Dutch enterprises across the Indian Ocean, the Pacific, and the Atlantic. Their massive, efficiently built fleets became the backbone of an extensive global trade network, securing the Netherlands’ position as the world’s leading maritime power in the 17th century.

The Flying Dutchman was Dutch East Indies ship destroyed by a fierce storm near the Cape of Good Hope in 1680. A ghost version of ship has reportedly been seen several times. In March, 1939, for example, about 60 people on Glencairn beach in South Africa reportedly saw a 17th century ship sail towards a sandbar and then disappear. The Flying Dutchman was immortalized by a Wagner opera.

Dutch Wars

In the early 16th century, the Dutch scored important victories against the Spanish. In 1628 the Naval commander Piet Hein was greeted with a hero's welcome after he captured the Spanish Silver Fleet off the coast of Cuba. As he rushed into the arms of his wife and family his mother ordered him back to the ship to wipe off his feet.**

In the 17th century Britain and the Netherlands fought with each other for control of the world's seas over three periods (1652-54, 1665-67 and 1672-74). British and Dutch ships fought one another in waters off of Europe, the West Indies and Asia. The Three Days Battle off southern England (1652) resulted in the loss of 20 Dutch ships and the death of 3000 men.

In 1672, King Louis XIV invaded the Netherlands. The Dutch, allied with Britain, attacked by the sea and forced the French to withdraw in 1674. The French later defeated the Dutch in the Mediterranean and the Dutch and English formed an alliance that was solidified when William II of Orange married Mary daughter of King James III of England. In 1689, he became of England when James was dethroned.

Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age began in 1588 after the Spanish began to be expelled, the majority of population had converted from Catholicism to Calvinism, and money started to come in from its overseas colonies. Alan Riding of the New York Times wrote, "It was special time in Dutch history, characterized by political enlightenment and economic prosperity. Amsterdam grew from 31,000 people in 1578 to 200,000 in 1650. The Amsterdam stock exchange, the world's oldest, was founded in 1602.

What is perhaps even more remarkable is that is that during much of the Golden Age the Netherlands was at war with Spain in the Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) that ended with the Dutch Republic's independence formally recognized in 1648 by the Treaty of Münster. The end of Golden Age occurred when Dutch naval competition with the British was extinguished for good at the 1797 Battle of Campersdown.

The Dutch Golden Age began after the Spanish were thrown out, the majority of population had converted from Catholicism to Calvinism, and money started to come in from its overseas colonies. Alan Riding of the New York Times wrote, "It was special time in Dutch history, characterized by political enlightenment and economic prosperity. Amsterdam grew from 31,000 people in 1578 to 200,000 in 1650. The Amsterdam stock exchange, the world's oldest, was founded in 1602.

The mercantile materialists who made a fortune in the Golden Age were called liefhebbers (meaning "those who love to have"). They bought wonderful brick houses along the canals of Amsterdam, patronized artists like Rembrandt, Rubens and Van Dyck and took pride in displaying their unique possessions in curiosity cabinets (the forerunners of museums). Men dressed as they were depicted in Rembrandt painting in black satin suits, frilly lace collars and wide brimmed hats.

Unlike wealthy upwardly-mobile British merchants, who spent their money on large estates, the Dutch burghers stayed in the cities, if for no other reason that land was scarce in Holland and it often flooded. They concentrated their wealth on smaller spaces and also seemed very interested in science and knowledge.

In 1615 a "scholars privileges" included a generous allowance of tree beer and wine. Paintings of well-dressed prostitutes were often displayed in prominent places in people's homes. Among the items displayed in the curiosity cabinets were fleas, glasses, astrolabes from Italy, nautilus shells from the Philippines, coral spoons, ivory flutes, coconut shell cups, microscopes, telescopes, armillary spheres, exotic seashells, rhino horns, elephant teeth. ostrich eggs and Roman coins. They also collected Turkish rugs, Greek marbles and trained monkeys and other curious pets.

Book: “Embarrassment of Riches” by Simon Schama "lavish study of the Netherlands during the Golden Age."

Tulip Mania

In the 1630s the Dutch became so enraptured with tulips that huge prices were spent on them; tulips became a symbol of wealth; and a highly speculative market grew up in which bulbs were bought and sold before they bloomed in a manner that was not unlike today’s Futures market. “Tulip Mania” spawned tulip analysts, special stock markets that dealt with trading tulips, and firms that specialized in insuring, storing, shipping and packing the flowers. "In 1634," Charles Mackay wrote in “Extraordinary Popular Delusions & the Madness of Crowds”, "the rage among the Dutch to possess (tulips) was so great that the ordinary industry in the country was neglected."

Between 1634 and 1637 speculation on tulips reached such a level it almost bankrupted the country. Individual bulbs for tulips of extraordinary color and patterns sometimes sold for as much $10,000 in today's money. A sailor who accidently ate an extremely valuable bulb for breakfast, thinking it was an onion, was jailed jail on felony theft charges. A rich man paid 8,000 pounds of wheat, 16,000 pounds of rye, 4 oxen, 8 pigs, 12 sheep, 2 hogsheads of wine, 1,000 gallons of beer, 1,000 pounds of cheese, a braed, a suit if clothes and a silver drinking cup for one rare variety of a tulip called a "Viceroy."

To keep prices climbing some speculators released chickens, pigs and dogs in tulip fields to destroy tulip crops thereby increasing the value of their own bulbs. They also cornered the market of of valuable bulbs and then spread rumors the crops had been wiped out to cause panic buying of remaining bulbs. Finally the tulip bubble collapsed and many people lost their shirt

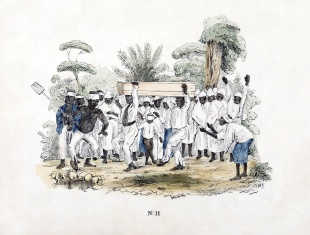

Dutch Slavery

Dutch slavery involved the forced abduction and transportation of around 600,000 Africans to Dutch colonies in the Americas and Asia from the 17th to 19th centuries, where they toiled on plantations producing sugar, coffee, and other crops, generating immense wealth for the Netherlands, which was among the last European nations to officially abolish the practice in 1863. The Dutch West India Company (WIC) managed much of this trade, with major hubs in Curaçao, Suriname, and parts of Africa, creating a brutal system that forms a painful, often overlooked, part of Dutch history, now prompting apologies and re-evaluation. There was some slavery in Indonesia and Asis but not to the extent of that in the Americas.

In 2021, Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum hosted an exhibition titled “Slavery,” which unflinchingly confronts the Dutch role in the global slave trade. One the first objects encountered was slender iron rod, with the artistically intertwined letters GWC. That was once used to brand the initials of a Dutch trading company into the skin of enslaved people. The stark contrast between refinement and brutality—between wealth and inhumanity— was a noticeable feature of the exhibition. Near the branding iron, a massive wooden set of stocks and heavy iron chains used to restrain enslaved men and women stands beside a small, lavishly decorated box of gold, tortoiseshell, and velvet. The box celebrates the prized commodities traded by the Dutch West India Company in the 18th century: gold, ivory, and human beings. [Source: Mike Corder, Associated Press, May 18, 2021]

Amsterdam, whose grand canal houses were built on fortunes made during the Dutch Golden Age, played a central role in the slave trade The exhibition told the history of slavery through the intimate stories of ten individuals—from enslaved laborers to a wealthy Amsterdam woman. The ten personal narratives span 250 years and four continents—Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa.

One of these stories is that of Wally, an enslaved man forced to work on a sugar plantation in the Dutch colony of Suriname. His story is narrated by former kickboxing world champion Remy Bonjasky, whose ancestors labored on the same estate. In 1707, Wally became embroiled in a conflict with plantation overseers. He and several others fled, were captured, interrogated, and executed. “They were to have their flesh torn off with red-hot pincers while being burned alive,” Bonjasky recounts. Their severed heads were later displayed as a warning. “The strength shown by Wally and the others is still in my blood,” he adds. “It helped me become a three-time world champion.”

In stark contrast stands Oopjen Coppit, the widow of Marten Soolmans, whose father owned Amsterdam’s largest sugar refinery—supplied by crops harvested by enslaved workers in South America. She embodies the wealth enjoyed by a privileged few at the expense of enslaved laborers. In Rembrandt’s 1664 full-length portrait, she appears in a black lace-trimmed gown adorned with pearls.

Oopjen’s second husband, Maerten Daey, also had direct ties to slavery. Before their marriage, he served with the Dutch West India Company in Brazil, where he kidnapped and raped an African woman, Francisca, fathering a daughter in 1632, according to church records cited in the exhibition. “The lives of Marten, Oopjen, and Maerten are intertwined with the history of slavery,” Rijksmuseum director Taco Dibbits explains in the audio tour. “Their wealth depended on slave labor in Brazil. It is a clear example of how the history of slavery and the history of the Netherlands are inseparable.”

Early Dutch Explorers

After Spanish were thrown out the Netherlands, the Dutch began looking beyond Europe to develop trade, harnessing their long-standing sailing tradition. The Dutch navigator Willem Schouten (1580-1625) rounded Cape Horn in 1616. Abel Janszoon Tasman was sent by the Dutch East India Company to find if New Guinea was attached to Australia. He instead found New Zealand, Tasmania and the Fiji Islands. The voyage was considered a failure because no ways of making money were discovered.

Early Dutch explorers of the 17th-century Dutch Golden Age played a major role in mapping large parts of the world, particularly the coasts of Australia—then called New Holland—as well as regions of Asia and North America. Sailing for the powerful Dutch East India Company (VOC), they sought new trade routes, access to valuable resources, and opportunities to expand Dutch commercial influence. Their voyages resulted in some of the earliest European charts of vast, previously unknown territories and helped establish far-reaching global networks.

Willem Janszoon was the first recorded European to land in Australia, reaching the Cape York Peninsula in 1606 aboard the Duyfken and beginning the Dutch charting of the continent. In the decades that followed, Abel Tasman’s voyages of 1642–44 led to the first European sightings of Tasmania, New Zealand, and Fiji, and further mapped Australia’s northern and western shores, reinforcing the name “New Holland.” Other explorers contributed key discoveries as well: Dirk Hartog landed on Australia’s western coast in 1616, leaving behind a famous pewter plate; Willem Schouten and Jacob Le Maire opened a new route around Cape Horn the same year, bypassing Spanish control of the Strait of Magellan.

Dutch exploration extended far beyond Australia. Henry Hudson, an English navigator sailing for the Dutch in the early 1600s, explored North America in search of a western passage to Asia, paving the way for Dutch settlement in the Hudson River region. In the far north, Willem Barentsz led late-16th-century expeditions to find a Northeast Passage to Asia, discovering Spitsbergen and giving his name to the Barents Sea. Completing the era’s achievements, Olivier van Noort became the first Dutchman to circumnavigate the globe in 1601. Together, these explorers helped transform the Dutch Republic into one of the world’s leading maritime powers.

Early Dutch Explorers in Australia

Most of the first Europeans to explorers Australia were Dutch. They mapped the western and northern coasts and named the continent New Holland but made no attempts to permanently settle it.

Thirty Dutch navigators explored the western, northern and southern coasts of in the 17th century. In 1616, Dirk Hartog was blown into the west coast of Australia and scoped it out a bit. Frederick de Houtman did the same in 1619. In 1623 Jan Carstenszoon followed the south coast of New Guinea, missed Torres Strait and went along the north coast of Australia. In 1643, Abel Tasman missed Australia, found Tasmania, continued east and found New Zealand , turned northwest, missed Australia again and sailed along the north coast of New Guinea. In 1696, Willem de Vlamingh explored the southwest coast.

It is at least plausible that early Portuguese explorers sighted Australia but the European who is credited with discovering it is Dutch captain Willem Janszoon, in 1606. From about 1611, the standard Dutch route to the East Indies (present-day Indonesia) was to follow the roaring forties, which ran south of Indonesia, as far east as possible and then turn sharply north to Batavia (present-day Jakarta) on the Indonesian island of Java. Since it was difficult to know longitude some ships reach the west coast of Australia or be wrecked on it.

The Dutch followed shipping routes of the Dutch East Indies used for trading spices, china and silk. There are many old shipwrecks of the west coast of Australia. Some of them belong to Dutch East India Company that missed the turn Batavia. A slight miscalculation could result in a terrible tragedy. One of first ships to go down was the “Batavia”. It ran aground in 1628. By the time help arrived three months later the crew had mutinied, resulting in the deaths of 120 people.

Many early Dutchmen in Australia were were shipwrecked on the rugged western coast. In 1616 Dirk Hartog landed on an island off Shark Bay and nailed a plate into a tree and left. In 1667 another Dutch explorer arrived and removed the plate and replaced it with another and left. In 1622–23 the Dutch ship Leeuwin made the first recorded rounding of the south west corner of the continent, and gave her name to Cape Leeuwin. In 1627 the south coast of Australia was accidentally encountered by Dutch-French navigator François Thijssen. He named and named it Land van Pieter Nuyts, in honour of the highest ranking passenger, Pieter Nuyts, the Councillor of India. In 1628 a group of Dutch ships was sent by the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies Pieter de Carpentier to explore the northern coast. These ships made extensive examinations, particularly in the Gulf of Carpentaria, named in honour of de Carpentier. In 1696, Willem de Vlamingh explored the southwest coast of Australia and discovered Perth’s Swan River.

The Dutch made no effort to settle or claim Australia. Early Dutch navigators considered Australia to be wasteland and felt it had few commercial possibilities.

See Separate Article: DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA BY EUROPEANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Dutch in the Pacific Ocean

On the Asian side of the Pacific Ocean the Dutch defeated and outmaneuvered the Portuguese and took control of the trade routes from the East Indies and Japan to Europe. One hundred years after the Spanish and Portuguese the Dutch Republic began its remarkable expansion. The Dutch reached the East Indies in 1596, the Spice Islands in 1602 and in 1619 founded Batavia (present-day Jakarta) in what is now Indonesia. In 1599, the first Dutch ships passed through the Strait of Magellan. In 1600 this fleet of Dutch ships reached Japan from. Will Adams, the first Englishman to reach Japan, was on board. Olivier van Noort followed and became the first Dutch circumnavigator. In 1722, the Dutchman Jacob Roggeveen sailed from Cape Horn to Batavia and discovered Easter Island and Samoa. [Source: Wikipedia]

Following the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 and other political changes in Europe, the hegemony of the Spanish and Portuguese in the Pacific was drastically reduced. Eric Kjellgren wrote: In the early seventeenth century the Dutch seized control of the Moluccas from the Portuguese and, as a result of both intentional expeditions and chance encounters by spice traders blown off course, began to chart the northern and western coasts of Australia. The Dutch exploration of the Pacific culminated with the voyage of Abel Janszoon Tasman (1603?-?1659) from 1642 to 1643. Sailing south of Australia, Tasman encountered Tasmania and Aotearoa. He later visited Tonga and Fiji, as well as New Ireland and other parts of Island Melanesia. Tasman 's journal includes an illustration of three New Ireland men in a canoe, whose openwork prow and stern ornaments, though somewhat fancifully rendered, are similar to historical examples. This illustration is among the earliest images of Oceanic art to be seen in the West. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Terence E. Hays wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “The Pacific in the seventeenth century was largely the province of the Dutch. Their primary motivation was business, particularly in spices, and in 1602 they established the Dutch United East India Company. From their bases in the 'Dutch East Indies" (Malaysia and Indonesia), Dutch ships probed to the east, with Willem Schouten and Jacob le Maire sailing along the northern coast of New Guinea and eastward to Futuna and Tonga in 1616, and Abel Tasman exploring much of the southern coast of Australia as well as Tasmania, which now bears his name, and as far east as Fiji in 1643.

Little of what the Dutch found was made public due to their concern with secrecy for purposes of trade monopoly, but sketchy reports trickled back to Europe and inspired such fanciful works of literature as Gulliver's Travels. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

Major Pacific Islands Discovered the Dutch

1616: Friendly Islands (Niua Islands of Tonga) and the Bismarck Archipelago by Willem Schouten from Cape Horn.

1642: Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania), New Zealand, the southern Friendly Islands (Tonga), and the Cannibal Isles (Fiji) by Abel Tasman

1722: Easter Island and the Navigator Islands (Samoa) by Jacob Roggeveen from Cape Horn

1741: Aleutian Islands by Vitus Bering and Alexei Chirikov from Russia [Source: Wikipedia]

The Dutch had little success in China but established themselves at Hirado, Nagasaki in 1609 and monopolized the Japan trade from 1639. In 1639 Matthijs Quast and Abel Tasman searched the empty ocean east of Japan looking for two islands called 'Rica de Oro' and 'Rica de Plata'. In 1643 Maarten Gerritsz Vries reached and charted Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. In 1653 Hendrick Hamel was shipwrecked in Korea. At about this time the Russians reached the Pacific overland via Siberia. It is significant that the Russian and Dutch trades were never linked since Siberian furs might easily have been exported to China at great profit.

Dutch in the Americas and Caribbean

In 1609, Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing under the Dutch flag, explored the river that now bears his name and claimed Nieuw Amsterdam for Holland. Hudson was looking for a passage to Russia and Asia through North America. He called the river "the cleanest river man has ever set eyes on" and went as far as present-day Albany before concluding he wouldn't reach the Pacific. Later, on another expedition to find a Northwest Passage, Hudson was set adrift in the Arctic Ocean by his mutinous crew and never heard from again. Dutch lost control of the Hudson river within 40 years after New Amsterdam was founded in 1624 but the culture lingered. In 1664 Nieuw Amsterdam became English New York. People spoke Dutch at home in villages near Albany until 1890.

It was a Dutchman who bought Manhattan from the Indians in 1626 for $24 worth of cloth and beads. The land covered 22 square miles. A Dutchman wrote home, "Our people have purchased the island of Manhattan from the Indians for the value of 60 guilders." New York was originally called Neiuw Amsterdam. Nina Ascoly wrote in American Heritage magazine, "Trade with America was a free-for-all until 1621, when the West India Company secured exclusive commercial rights in Nieuw Amsterdam. The monopolistic company offered generous incentives to colonists."

The Dutch are credited with introducing Santa Claus, perhaps Thanksgiving (perhaps based in an annual commemoration of the 1574 lifting of a Spanish siege on Leiden in 1574), ladder-back chairs, wood-planked house construction, civil marriages, care for the poor, division of colonies into boroughs to the United States.

Outside of Asia and the tri-state area many Dutchmen were slave traders. The West India Company had a monopoly on the lucrative trade for slaves to the Caribbean from Angola, a Portuguese colony where many slaves originated. Dutch colonization in the Caribbean began in the 1630s, primarily driven by the Dutch West India Company (WIC), focusing on strategic trading posts and sugar/salt production, leading to settlements on islands like Curaçao, Aruba, Bonaire, St. Eustatius, Saba, and Sint Maarten, which evolved into the Netherlands Antilles (Dutch Caribbean) and remain part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands today. These islands served as vital hubs, often contested with other European powers, and their economies relied heavily on slave labor for lucrative commodities like sugar, tobacco, and salt.

Durch Golden Age Shipwreck

The Burgzand Noord 17 shipwreck, found off Texel, about 90 kilometers (55 miles) north of Amsterdam in 2009, is one of the richest archaeological discoveries of 17th-century luxury goods ever recovered from the sea. The Dutch vessel, which sank sometime after 1636, carried an extraordinary cargo that reflects the global trade networks of the Dutch Golden Age. Excavations uncovered rare silk and velvet garments, fragments of a knotted silk-and-wool carpet likely made in Lahore, book covers, pottery, mastic resin from Chios, and finely tailored caftans possibly linked to the Ottoman court or Eastern Europe. [Source: Tracy E. Robey, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

The ship’s identity and purpose remain uncertain. It may have been a straatvaarder—a merchant ship built for voyages beyond Gibraltar—or a vessel collecting goods in Amsterdam to transport elsewhere. Among the most unusual finds is a large quantity of unworked boxwood, the first archaeological evidence of raw boxwood transport. This expensive, fine-grained wood was prized for detailed carvings and luxury objects, though its origin remains unclear.

The absence of expected items—especially linen or cotton undershirts that would normally accompany the luxurious silk gown found on board—raises questions about whether the clothing belonged to passengers or was cargo intended for sale. By contrast, one pair of finely knitted silk stockings survived, representing elite fashion of the period. Overall, the Burgzand Noord 17 wreck offers a rare and vivid glimpse into 17th-century global commerce, cross-cultural exchange, and the material world of European elites.

Texel — the Busy Port Off Amsterdam

Tracy E. Robey wrote in Archaeology magazine: “On busy days in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, hundreds of ships would anchor on the eastern side of Texel. For large vessels, the island was as close as they could come to the trading capital of Amsterdam because of a sandbank in the city’s harbor called Pampus — a small island there bears the same name today. Large ships would load and unload their cargo without ever traveling the 55 miles south to Amsterdam’s port, relying on smaller boats and carts to move the goods. Warships such as man-of-war frigates would even drop off their cannons at Texel for servicing in Amsterdam as there was simply no way for large ships to pull into the tricky harbor — unless a spring tide, just after a new or full moon, miraculously eased their way by raising the sea level. [Source: Tracy E. Robey, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2018]

“So many ships anchored at Texel that when nasty storms blew in, losses could be catastrophic. On Christmas night in 1593, 24 ships of a fleet of 150 went down. And in early November 1638, 35 ships sank in a single storm. In addition to experiencing frequent storms that doomed ships, Texel and Amsterdam also compared unfavorably to nearby Rotterdam, which offered sailors an easy way to pull in and out of its harbor. It had none of the sailing around Texel and the possibility of having to wait 10 or 12 days for the right burst of wind to propel the ship from what was then known as the South Sea. Even into the nineteenth century, books on navigation warned that although the sea to the east of Texel was mostly calm, it could be choppy when wind came from the west and southwest, with sailing further complicated by the fact that the seafloor near the island was soft mud. They suggested that it was better to anchor in deeper water with firmer ground below, out where the water was 60 to 75 feet deep, to avoid putting down as many as four anchors to no avail.

“With such dangers and inconveniences, why did so many ships continue to anchor at Texel each day in order to do business with Amsterdam? Because as the Netherlands raced to the forefront of culture, trade, and science in the seventeenth century, resulting in the period now called the Dutch Golden Age, by funding from the Bank of Amsterdam and the first stock exchange, investors enabled ships to set out from Texel to explore the world. From Amsterdam — or, rather, from Texel — Dutch East India Company vessels sailed off to trade with areas as varied and far away as Indonesia and Japan, while other Dutch ships went to the Caribbean, Brazil, and North America. They moved everything from spices and silk to sugar and slaves. In this era, ships were mobile, but fragile, packets of wealth.

“Shipping had always been dangerous, and the desire to mitigate risk led to the invention of shipping insurance in medieval Italy. Shipping also helped foster early modern café culture and newspapers. Businessmen gathered over coffee and tobacco to wait for news, word of ships’ arrival, and gossip, while newspapers published reports of vessels lost at sea, even in distant locations. As European trade operations spread around the world, information networks metaphorically, and sometimes literally, ran alongside shipping lanes, supporting the new global empires.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025