SPICES AND THE SPICE ISLANDS

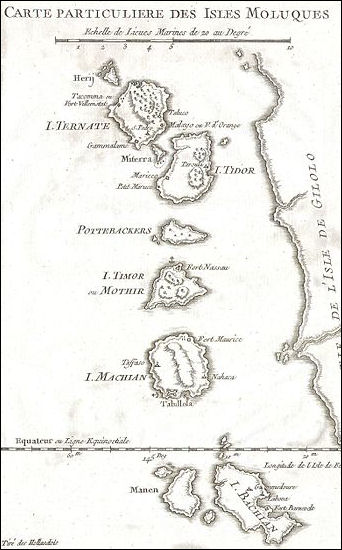

Map of the Moluccas

Ternate and its neighboring islands were the natural home of the clove tree, while the Banda Islands were the only place where the nutmeg tree grew naturally, producing both nutmeg and mace. All these islands are in the Moluccas in what is now Indonesia. Until the sixteenth century, the cultivation of cloves, nutmeg, and mace was confined to these islands alone. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Cloves were the most valuable early spice. They originated from the islands of Ternate, Tidore and Bacan in the Molucca group in Indonesia. Traded as far as Syria as early as the 18th century B.C., cloves first came into high international demand during the Han dynasty in China and the Roman Empire in the West. Traders en route between the north Javanese ports and the clove-trading sultanate of Ternate (Muslim since the 15th century) made stopovers at Hitu on the north coast of Ambon island. Before the birth of Christ, visitors to the Han Dynasty court in China were only permitted to address the emperor if their breath has been sweetened with “odoriferous pistols” — Javanese cloves. Because of limited geographical range cloves didn’t make their way to Europe until around the A.D. 11the century. They were introduced by Arab traders who controlled the trade of many spices to Europe.

Nutmeg was also greatly valued not only as a flavoring for food but also as a cure fir illnesses including the bubonic plague.. It takes very little effort to grow. Diane Selkirk of the BBC wrote: At the time, nutmeg only grew in the Banda Islands. A combination of the region’s isolation and the finicky nature of the nutmeg tree kept the price astronomical. Nutmeg will only grow in specific conditions: fertile, well-drained soil in a tropical climate that gets lots of rain. Even then the trees only fruit after seven to nine years, and the labour-intensive process of harvesting requires workers to handpick each fruit and remove the outer covering, before carefully peeling off the mace (a delicate, saffron-coloured spice), drying the seed and cracking off the hard shell. [Source: Diane Selkirk, BBC, October 12, 2017]

Life on the nutmeg islands was good and easy the islanders that raised it. They had do little but watch the nutmeg grow, collect it from trees and take out the nuts and trade them for food, cloth and all the things they needed with Chinese, Malay, Arab and Bugi spice traders. The was competition between Muslims and Chinese over control of the Indonesian spice trade.

Websites and Resources: Different Spices spice-trade.com/types-of-spices ; Spice Plants uni-graz.at/~katzer ; Spice Farming spices.indianetzone.com/1/spice_farming.htm ; History of Spice Trade celtnet.org.uk/recipes/spice_trade ; History Spices, Spices Indian Trade Zone spices.indianetzone.com/ ; Encyclopedia of Spices theepicentre.com/Spices ; McCormik Spice Encyclopedia mccormick.com ; Wikipedia article on Spices Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the Spice Trade Wikipedia ; Book: “ Spice” by Jack Turner (Knopf, 2004)

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOLUCCAS: GEOGRAPHY, ISLANDS, WILDLIFE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: HISTORY, IDENTITY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: LIFE, SOCIETY, FAMILY, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

MALUKA (CENTRAL MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

BANDA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS FIRST ARRIVED: SPICES, POWERFUL STATES, DEALS, ISLAM factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDIANS, CHINESE AND ARABS IN INDONESIA: IBN BATTUTA, YIJING, ZHENG HE factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PORTUGAL AND THE AGE OF DISCOVERY factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE TRADE EMPIRE IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

DUTCH EMPIRE: WEALTH, EXPLORATION AND HOW IT WAS CREATED factsanddetails.com

END OF THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY, BRITAIN IN INDONESIA AND THE JAVA WAR factsanddetails.com

NETHERLANDS INDIES EMPIRE IN THE 19TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com

Early Spice Trade

From ancient times, these spices were highly prized commodities, commanding extremely high prices in the markets of Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Over time, foreign traders made their way to the Moluccas—also known as the Spice Islands. Javanese merchants were almost certainly the earliest visitors, followed by traders from South Asia and the Middle East, and finally, in 1512, by the Portuguese. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

During the Middle Ages, Chinese, Arab and Malay traders purchased nutmeg in what is now Indonesia and carried it in boats to the Persian Gulf or by camel and pack animal on the Silk Road. From the Gulf the spices made their way to Constantinople and Damascus and eventually Europe.

For a long time the spice trade was controlled by north Moluccan sultanates, name Ternate, founded in 1257, and Tidore, founded in 1109. Both were based on small islands and often fought among themselves. Their most valuable crop was cloves. Protecting their kingdoms were fleets of “kora-kora” , war canoes manned by over 100 rowers. The sultans relied on Malay, Arab and Javanese merchants to distribute their goods.

Moluccas (The Spice Islands)

By the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, expanding trade contacts between Ternate–Tidore, the Banda Islands, and the wider world coincided with the spread of Islam. At the same time, processes of state formation took place in the North Moluccas, resulting by the early sixteenth century in four principalities: Ternate, Tidore, Jailolo, and Bacan. Among these, Ternate and Tidore emerged as the most powerful. They were evenly matched rivals and were almost constantly in conflict. Ternate generally enjoyed the support of Bacan, while Jailolo tended to ally with Tidore. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

No comparable state formation occurred in Banda. In the sixteenth century, Bandanese society consisted of more than twenty villages lacking a centralized authority. Village leaders, commonly known as orang kaya (“rich men”), occasionally fought one another but cooperated when shared interests—particularly in dealing with foreigners—were at stake. Despite the absence of a state, Banda possessed a form of supravillage organization. The villages were divided into two opposing alliances: the Uli Lima, or League of Five, and the Uli Siwa, or League of Nine. Each village belonged to one of these leagues, creating a dual territorial division in which the two groupings regarded one another as rivals.

A similarly structured village order existed in the Central Moluccas. Prior to the sixteenth century, the Central Moluccan islands were of little importance and were inhabited by populations considered relatively undeveloped. However, because Ambon lay along the sailing route between Banda and Ternate–Tidore, its inhabitants came into regular contact with foreign traders. As a result, early in the sixteenth century, villages in Hitu, on the northern peninsula of Ambon, began cultivating cloves. Around the same time, Islam was adopted in Hitu. This was the political, economic, and religious landscape of the Moluccas when the Portuguese arrived in the early sixteenth century as the first Europeans to reach the region.

See Separate Articles:MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com; NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com; MALUKA factsanddetails.com; BANDA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

Spices in Ancient and Medieval Europe

.png)

location of the MoluccasSpices such as cinnamon and pepper that were known in ancient Rome and traded on the Silk Road originated from India and the East Indies. Pliny wrote of how cinnamon and other spices from Indonesia reached Rome via Madagascar and East Africa. By the A.D. 1st century, spices were making their way to China and India and from there taken by ship and Silk Road caravans to Europe.

Spices were among the most valuable commodities carried on the Silk Road. Without refrigeration food spoiled easily and spices were important for masking the flavor of rancid or spoiled meat. Basil, mint, sage, rosemary and thyme cold be grown in family herb gardens in Europe along with medicinal plants. Among the the spices and seasonings that came from the East — affordable to merchants and burghers but not ordinary people — were pepper, cloves, mace and cumin. Ginger, nutmeg, cinnamon and saffron — the most valuable of spices from the East — were worth more than their weight in gold.

Pepper, one of the spices that Columbus was looking for when he landed in the America in 1492, had been coming to Europe along the Silk Road at least since Roman times, when many Roman cookbook recipes called for pepper. In the A.D. first century, the satirist Persius wrote:

The greedy merchants, led by lucre, run To the parch'd Indies and the rising sun From thence hot Pepper and rich Drugs they bear, Bart'ring for Spices their Italian ware...

During the Middle Ages, one medieval town sold 288 kinds of spices, many of whom had an unknown origin. Cinnamon, people were told, came from an exotic bird and cloves were netted in the Nile by Egyptians. Caravans that carried pepper were heavily armed.

Early European Explorers and the Spice Islands

European countries could not grow spices. Spices had to pass complicated route to reach Europe, thus causing them to be very expensive. Europeans concluded it'd be much cheaper to come to the source of the spices. In 1511, the Portuguese built their first fort in the area on the island of Ternate, and cornered the clove trade. The Dutch, who arrived in 1599, mounted the first serious threat to Pourtuguese control of Maluku’s treasures. Armed conflicts broke out, taking a heavy toll from the island populations as well as the rival European powers. When the Dutch finally emerged as victors they enforced their trade monopoly with an iron fist. Whole villages were razed to the ground and thousands of islanders died, especially on the island of Banda. The British briefly occupied Maluku during the Napoleonic Wars, but Dutch rule was restored in 1814 and it wasn’t until 1863 that the compulsory cultivation of spices was abolished in the province.

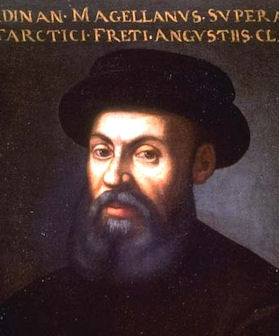

Ferdinand Magellan Early maps of Indonesia showed the archipelago as the place "Where Dragons and Leviathans be." In 1510, a Bolognese traveler named Ludovico di Varthema returned to Italy after a six year trip in the East. He published an account of his journey that drew considerable attention. Among other things he was the first to European to describe nutmeg trees growing in the Banda Islands in what used to be called the Spice Islands and what are now called the Moluccas. They were the only places in the world that nutmeg grew.

The Spice Islands that Columbus was looking for were the Moluccas. After Magellan was killed in the Philippines his crew loaded up with spices in the Moluccas for the journey home. At that time nutmeg and cloves were worth more than gold. "When the cloves sprout," wrote Pigafoote, "they are white; when ripe, red; and when dried, black...Nowhere in the world do good gloves grow except on five mountains of those five islands."

Sir Francis Drake visited the islands of Indonesia and turned an offer of cheap and valuable cloves because his ship was so full of stolen Spanish goods. When he returned his trans-global voyage one of the items he brought back that caused the biggest stir was a mermaid from Sumatra that looked an awful lot alike the upper half of a monkey glued to the tail of a fish.

Spices and the Opening Up of Indonesia

The early modern age of commerce in Indonesia was initially fueled by the buying and selling of Indonesian spices, the production of which was limited and the sources often remote. Nutmeg (and mace) come from the nut of the tree “Myristica fragrans”, which, until the late eighteenth century, grew almost exclusively on six tiny islands in the Banda Archipelago, some 300 kilometers west of the Papua coast. Cloves are the dried flower buds of the tree “Syzygium aromaticum”, the cultivation of which until the mid-seventeenth century was largely limited to a handful of small islands off the west coast of Halmahera in the Maluku Islands. [Source: Library of Congress *]

These spices had long been distributed in modest quantities via the trade networks of the archipelago. After about 1450, however, demand and the ability to pay for them climbed rapidly in both China and Europe. In the century between the 1390s and the 1490s, for example, European imports of cloves rose nearly 1,000 percent, and of nutmeg nearly 2,000 percent, and continued to rise for the next 120 years. Another product, black pepper “(Piper nigrum”), was grown more easily and widely (on Java, Sumatra, and Kalimantan), but it too became an object of steeply rising worldwide demand. These changing global market conditions lay at the bottom of fundamental developments, not only in systems of supply and distribution but in virtually all aspects of life in the archipelago. *

See Separate Article SPICES AND POWERFUL STATES IN INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS ARRIVED factsanddetails.com

Malacca Kingdom, Ternate and Tidore

By the 15th century the predominate power in Indonesia was Malacca (Melaka), the trading kingdom based on the Malay peninsula. The Melaka kingdom controlled the strategic shipping lanes of the Malacca Straits and important commercial ports on northern Java. By the 16th century Melaka was the supreme power in Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

The commencement of the current Malay nation is often traced to the fifteenth-century establishment of Malacca (Malacca) on the peninsula’s west coast. Malacca’s founding is credited to the Srivijayan prince Sri Paramesvara, who fled his kingdom to avoid domination by rulers of the Majapahit kingdom.

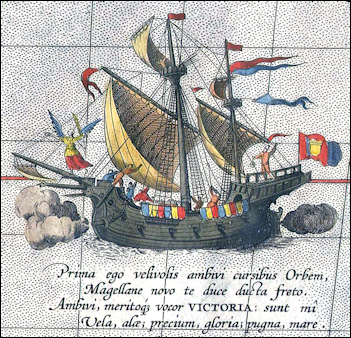

Magellan's ship Early Malaysian cities and states originated in the coast and then moved to interior. These traded expensively with Chinese traders, who began arrived in numbers in the 14th century. Groups such as the Acehese, the Bugis and the Mnangkabau fought for dominance over the peninsula.

Malacca was founded in 1402 by Paramesvara, a prince who fled from Sumatra and established a port which attracted trading ships from as far away as China, India and the islands near New Guinea. These ships carried sandalwood, pearls, porcelain, silk, gold, tin , bird-of-paradise feathers and spices such as cloves, mace and nutmeg from the Spice Islands in what is now eastern Indonesia.

Ternate and Tidore islands were the home of powerful rival Muslim sultanates in pre-European times. Their influence at one time extended to the Philippines, Sulawesi and New Guinea. They were the two most powerful of the four kingdoms that controlled the clove trade until the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century. They held their own in battles against the Portugese and Spanish in the 1500s, but were eventually defeated by the Dutch and came under colonial rule.

The Ternatan and Tidorese of two small islands in the North Moluccas: Ternate and Tidore. Also known as Orang Ternate, Orang Tidore, Suku Ternate and Suku Tidore, they distinguish themselves from the islanders around them by the use of the Ternatan and Tidorese languages and their link to historical kingdoms. The Ternatan and Tidorese are closely linked culturally but neither likes to be confused with the other.

Portuguese and the Spice Trade

The Portuguese arrived in Indonesia in 1510. On the way back from Banda they were shipwrecked and made their way to Ambon and were subsequently invited to Ternate, where they came in contact with the sultan that controlled the source of nutmeg and cloves.

The Portuguese came to Indonesia to monopolize the spice trade of the eastern archipelago. Nutmeg, mace, and cloves were easily worth more than their weight in gold in European markets, but the trade had hitherto been dominated by Muslims and the Mediterranean city-state of Venice. Combining trade with piracy, the Portuguese, operating from their base at Melaka, established bases in the Maluku Islands at Ternate and on the island of Ambon but were unsuccessful in gaining control of the Banda Islands, a center of nutmeg and mace production. [Source: Library of Congress]

In 1511, Portuguese, in pursuit of controlling the valuable spice trade, captured the strategic commercial center of Meleka on the Malay Peninsula. This opened the way for direct passage to the islands that produced spices. The Portuguese wrested control of the spice markets and trade route from seafaring Muslim merchants.

In 1512, Portuguese explorers under Afonso de Alburqueque reached the Moluccas and claimed them for Portugal. They also loaded their hold with nutmeg and mace and sent them to Seville and made a fortune. The Portuguese restricted production of spice such as nutmeg and cloves to the islands of Banda and Ambonto conserve their monopoly.

In a effort to create a clove monopoly the Portuguese struck a deal with the sultan of Ternate in which they promised to help the Ternate sultan fight his enemy, the sultan of Tidore, in return for exclusive rights to cloves produced under the sultan. The sultan had no intention of complying with the terms but was forced to. The local Muslim resented the Portugese importation of pigs and their rough justice and rebelled when one sultan was executed and his head was displayed on a pike. In the meantime the Tidore responded by forming an alliance with the Spanish.

See Separate Article: PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Europeans and the Spice Islands

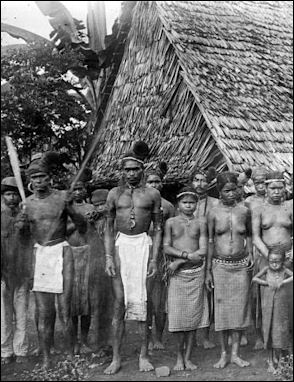

Spice Islands people The Portuguese were followed by Spanish, who claimed Portuguese territories when Philip II assumed the Portuguese crown in 1580. Like, the Portuguese, the Spanish established themselves by building forts and trading out of them. Later the British and Dutch fought over them and the Spanish retreated to the Philippines. The Dutch took possession of many of the Portuguese forts by force. The English. took a few islands in the Moluccas in the early 1700s and later established a short-lived colony of Sumatra. They didn’t stay long and focused their attention on Malaysia.

According to some scholars the spice trade before the Age of Discovery was peaceful and profitable to a large number of people until the Portuguese, Dutch, Spanish and English tried to bypass the traditional trade routes and set up monopolies. The voyages to the spice islands were financed by investors that included royal families, brokers and bankers. The profits were enormous if a ship actually returned with spices because the risks were enormous. Ships were lost to storms and reefs. If the managed to make it to their destinations in the Far East they were often robbed of their cargoes by Asian and European pirates on the way back.

Some of these complexities of controlling the spice trade—and maintaining a presence in Indonesia—can be glimpsed in a brief history of Ternate, Maluku, in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. In 1512 seven Portuguese arrived in Ternate as the guests of Sultan Abu Lais (r. ?–1522), having been rescued by fishermen from a shipwreck of their locally built vessel (their original ship had become too unreliable to continue in service) loaded with spices purchased in Banda. The sultan sought an alliance with the Portuguese, of whom he had already heard, and was eager to exchange cloves for assistance against the rival sultanate of Tidore. [Source: Library of Congress *]

When Spanish ships arrived in Maluku in 1521, Sultan Mansur of Tidore sealed a similar agreement with them, to which the Portuguese soon responded by building a large stone fortress on Ternate. This act touched off decades of warfare among Europeans and their local allies, in which political control, economic ascendancy, and religious identity all were contested. But it also brought change in Ternate itself, for the ruler there became essentially a prisoner of the Portuguese, whose increasingly arbitrary and oppressive interference in local affairs, including spice production and harvesting, eventually turned their former allies against them. *

Under the leadership of Sultan Babullah (r. 1570–83), Islam became a powerful tool with which to create alliances and gather widespread opposition to the Portuguese. After a siege in 1575 against the Ternate fort, he ousted the Portuguese forces. Babullah allowed a limited contingent of Portuguese merchants to continue trading in Ternate, but the fort became the royal residence, and the sultanate rapidly expanded its reach to key trading ports as far away as northern and southern Sulawesi until the arrival of the Dutch touched off new and even more complex struggles. *

Dutch in Indonesia

The Dutch began making moves on Indonesia once they mastered the “wild navigators,” the route westward to the Orient via Cape Horn. The Dutch began making moves on in present-day Indonesia after the Spanish Armada was defeated by the English in 1588. Much of the Dutch activity was chartered as the United East India Company (later the Dutch East India Company), a government-run monopoly created from competing merchant companies that were encouraged by the Dutch government to unify in 1601.

Cinnamon in SumatraThe first expedition — four Dutch ships led Cornelius de Houman — in 1595-97 was both a disaster and a success. One ship was sunk and half the crew and a Javanese prince were lost. The three remaining ships made it back to Holland with cargo holds filled with spices and earned huge profits for those that had invested in the expedition. Ultimately with bigger ships, more powerful guns and better financial backing than their European rivals, Dutch were able to gain control of the East Indies.

With exception of two brief periods of English rule during the turn of the 19th century, Indonesia was under Dutch rule from 1627 to 1942. During that time Indonesia was know variously as the Dutch East Indies, Dutch East India, the Netherlands Indies, the Malay Archipelago, Malaysia, or the East Indies.

The Dutch were interested primarily in commerce and plantation agriculture and making money. The exploited commodities such as spices, teak, coffee and tea and ruled in such a way as to make a maximum profit. Their strategy was to monopolize trade, fix prices and exploit the local population as a labor force. They did relatively little to develop and modernize Indonesia and were largely unsuccessful spreading Christianity.

See Separate Article: DUTCH, THE SPICE TRADE AND THE WEALTH GENERATED FROM IT factsanddetails.com

Dutch and the Spice Trade

The Dutch established a monopoly on the spice trade from the Moluccas . They gained control over the clove trade through an alliance with the sultan of Ternate in the Moluccas in 1607. Dutch occupation of the Bandas from 1609 to 1623 gave them control of the nutmeg trade. Dutch control of the region was fully realized when Melaku was captured from the Portuguese in 1641.

On the Banda Island, the Dutch tried to trade knives, woolen clothes and other things that the Banda islander didn’t need. The Dutch demanded that they be given a monopoly and found a few complaint chiefs that signed “contracts” promising them their desired monopoly. In the meantime the English had arrived in the area and they and the Dutch tried to battle and outmaneuver one another for control of the islands.

The Dutch could be quite ruthless when it suited their purposes. In the Bandas, one governor-general beheaded and quartered 44 local chiefs and displayed the remains in 1621 at a fort after Dutch “negotiators” were killed in a dispute over the placement of a fort on sacred site.

In what today is eastern Indonesia, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) with the help of indigenous allies fundamentally altered the terms of the traditional spice trade between 1610 and 1680 by forcibly limiting the number of nutmeg and clove trees, ruthlessly controlling the populations that grew and prepared the spices for the market, and aggressively using treaties and military means to establish VOC hegemony in the trade. One result of these policies, exacerbated by the late-seventeenth-century fall in the global demand for spices, was an overall decline in regional trade, an economic weakening that affected the VOC itself as well as indigenous states, and in many areas occasioned a withdrawal from commercial activity. [Source: Library of Congress]

See Separate Article DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2026