PORTUGUESE ESTABLISH THEIR TRADE EMPIRE IN ASIA

In the 15th century, Portuguese navigators started Europe's colonization of Asia. The Portuguese trading empire established itself in Asia with the seizure of Goa in India in 1510 and Malacca in present-day Malaysia in 1551. The Spanish and Portuguese were able to establish their large empires in Asia because they encountered virtually no resistance. The Sultanates in Malaysia and Indonesia were easy to overcome, Filipinos were just tribal farmers, and the Mughals in India didn't have much of a navy. The Portuguese and Spanish established themselves by building forts and trading out of them. Goa remained in Portuguese hands until 1961. There was a great deal of intermarriage between the Portuguese and local Kankani-speaking women. Portugese born on Indian soil were called “Castees” while those of mixed parentage were called “Mustees” or “Mestiz.”

After de Gama returned from his second voyage the Portuguese set about building their empire in India. Their first viceroy in India destroyed the Muslim Fleet. The next viceroy, Afonso Albuquerque, gained control over the Persian Gulf in 1507, established a Portuguese trading center in Goa in 1507, captured Malacca in 1511, which opened trade routes with Siam (Thailand), the Spice Islands (in present-day Indonesia) and China.

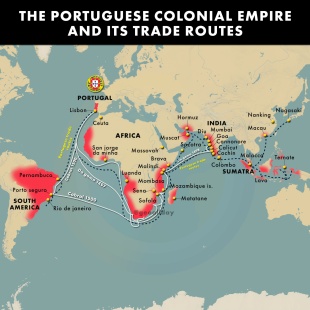

The papacy charged Portugal with converting Asia to Christianity. Equipped with superior navigational aids and sturdy ships, the Portuguese attempted to seize rich trade routes in the Indian Ocean from Muslim merchants. They established a network of forts and trading posts that at its height extended from Lisbon by way of the African coast to the Straits of Hormuz, Goa in India, Melaka, Macao on the South China coast, and Nagasaki in southwestern Japan.

Portuguese caravels with Portugal’s scarlet Cross of Christ dominated the seas and wrested control of the spice markets and East-Westtrade route from seafaring Muslim merchants. At its height the Portuguese empire included Brazil, large parts of Africa and almost all the important trading areas in China, India, southeast Asia and present-day Indonesia. [Source: Howard la Fay, National Geographic, October 1965].

Groups that financed voyages during the Age of Discovery included the Order of Christ, a wealthy religious organization that sprang up from the crusading Knights of Templar. The Portuguese king held on monopoly on pepper, perhaps the most profitable of all the spices. The two main casualties of Portuguese trade were Venice and the Muslims. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

Merle Severy wrote in National Geographic: "After the discovers became conquerors, they learned it was more profitable to keep Muslim trade and regulate and tax it. The Portuguese took their biggest profit from inter-Asian trade—selling Arabia's stallions to waring Indian princes, carrying cotton textiles around the Bay of Bengal and Timor's sandalwood to China, and bartering China's silk for Japan's silver." European and Asian trade was not simply a one way street. The Portuguese introduced corn, tobacco, pineapple, papaya, sweet potato, cashews and other plants to Asia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SPICES, TRADE AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA WHEN EUROPEANS FIRST ARRIVED: SPICES, POWERFUL STATES, DEALS, ISLAM factsanddetails.com

EARLY EUROPEAN EXPLORERS IN INDONESIA: MARCO POLO, NICOLÒ DEI CONTI, MAGELLAN'S CREW factsanddetails.com

AGE OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

PORTUGAL AND THE AGE OF DISCOVERY factsanddetails.com

EARLY DUTCH PERIOD IN INDONESIA AND THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY (VOC) factsanddetails.com

Violence and the Ease With Which the Portuguese Established Their Asian Empire

The Spanish and Portuguese were able to establish their large empires in Asia because they encountered virtually no resistance. The Sultans in Malaysia and Indonesia were easy to overcome, Filipinos were just tribal farmers, and the Monghols in India didn't have much of a navy. The Portuguese and Spanish established themselves by building forts and trading out of them. The Dutch later moved in and took possession of many of the Portuguese forts by force, which in turn were taken away from them by the English. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

"Portuguese galleons," historian K.N. Chaudhuri told Severy, "maximized the advantages of Europe's gunpowder revolution and artillery. With an added deck and gunports, the galleon became a floating fortress and floating warehouse." Portuguese mercenaries worked for everyone from Indian princes to the king of Siam. Their ability to use firearms often made the difference between victory and defeat. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

The Portuguese ships were armed to the hilt and their captains were not afraid to use power. "Vasco de Gama cut up the bodies of casually captured fisherman and traders," wrote Boorstin, "and sent a basketful of their hands, feats and heads to the Samurai of Calicut simply to persuade him into a quick surrender. Once in power, th Portuguese governed their India in the same spirit. When Viceroy lmeida was suspicious of a messenger who came under a safe-conduct to see him, he tore out the messenger's eyes. Viceroy Albuquerque subdued the peoples along the Arabian coast by cutting of the noses of their women and the hands of their men. Portuguese ships sailing into remote harbors for the first time would display the corpses of recent captives hanging from the yardarms to show that they meant business.” [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

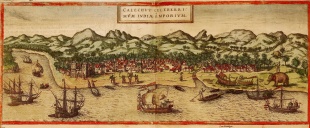

Alvares Cabral sailed to India in 1500 and lost 6 of 13 ships. "God gave the Portuguese a small country for a cradle, a Jesuit missionary once wrote, "but the whole world for a grave." When Cabral arrived two year after de Gama there were clashes with Muslim traders in Calicut and the Portuguese ended up establishing their capital in Cochin, a rival kingdom down the coast. [Source: Howard la Fay, National Geographic, October 1965].

Afonso de Albuquerque

Afonso de Albuquerque (14??-1515) was a Portuguese soldier and explorer who sailed to the Spice Islands in 1507-1511 and tried to monopolize trade in the area for Portugal. From Europe, he sailed around Africa to the Indian Ocean. He was appointed the Viceroy of India by King Emmanuel in 1509. He forcibly destroyed the Indian city of Calicut in January, 1510, and took Goa (in southern India) in March, 1510, claiming Goa for Portugal.

Afonso de Albuquerque, or Afonso the Great, was a formidable soldier who is credited with creating the Portuguese empire after Dias and De Gama figured out how to get to the Far East. Starting in 1503, he conquered the strategic Indian ocean ports, one by one, wrestling control of lucrative spice trade away from the Muslims. His most important achievements were the 1510 capture of Goa, the river moated trading center in western India that remained a Portuguese procession until 1961, and the establishment of control over in 1511 over the Straits of Malacca, off of present-day Singapore, the route which nearly all the ships carrying silk and spices from China and the East Indies had to travel through. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

Later Albuquerque captured the straits of Hormuz chocking of the Muslim trade into the Persian Gulf and sent emissaries that discovered that most of the spices originated in the Moluccan islands in the East Indies. To attain immorality Albuquerque planned to capture Jerusalem from the Arabs by digging a canal to the Nile, and starving the Egyptian Mamluks by draining the life-giving waters into the Red Sea, and seizing Mohammed's body in Medina and holding it ransom. For their part the sultans who controlled the Holy Land and the Middle East threatened to destroy Christ's tomb in Jerusalem. [Ibid]

Portuguese and the Spice Trade

After Vasco de Gama discovered the sea route to India Portuguese ships monopolized the spice trade. Portugal grew rich on the trade between Asia and Europe and the Venetians, Genovese and Muslim sultans that controlled the East-West trade before de Gama's voyage all suffered. European consumers also benefitted. The price of pepper in Lisbon was one of what was when the pepper trade was controlled by Egyptian sultans.

Portugal established a pepper monopoly by 1504. Why were spices so important? One reason: Without refrigeration food spoiled easily and spices were important for masking the flavor of rancid or spoiled meat. Meat was preserved by "salting," a process that required large quantities of pepper in addition to salt to counteract the "unpalatable effects of the slat itself."

The Malabar Coast of India and the islands of Indonesia have traditionally been the sources of peppercorns for pepper. The best pepper is said to come extra large peppercorns named after Tellicherry on the Arabian Sea.

Cloves were the most valuable early spice. They originated from the islands of Ternate, Tidore and Bacan in the Mollucca group in Indonesia. Before the birth of Christ, visitors to the Han Dynasty court in China were only permitted to address the emperor if their breath has been sweetened with “odoriferous pistols” — -Javanese cloves. Because of limited geographical range cloves didn’t make their way to Europe until around the A.D. 11the century. They were introduced by Arab traders who controlled the trade of many spices to Europe.

During the Middle Ages, Chinese, Arab and Malay traders purchased nutmeg in what is now Indonesia and Southeast Asia and carried it in boats to the Persian Gulf or by camel and pack animal on the Silk Road. From the Gulf the spices made their way to Constantinople and Damascus and eventually Europe.

For a long time the spice trade was controlled by north Moloccan sultanates, name Ternate, founded in 1257, and Tidore, founded in 1109. Both were based on small islands and often fought among themselves. Their most valuable crop was cloves. Protecting their kingdoms were fleets of kora-kora , war canoes manned by over 100 rowers. The sultans relied on Malay, Arab and Javanese merchants to distribute their goods.

See Separate Article: PORTUGUESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Piracy, Monopolies and Free Trade and East-West Trade

Jean-Philippe Vergne of Bloomberg wrote: “The rise of piracy coincides with the international trade revolution. In 1498, Vasco da Gama sailed from Portugal around the Cape of Good Hope and opened the route to the East Indies. Over the next 15 years, Portugal sent armadas to the Indies to eliminate the competition from Muslim traders. This marked the beginning of a new form of economic organization: the establishment of trade monopolies by European states. The Portuguese crown wanted to capitalize on the new trade opportunities that were opened by da Gama. To do this, a royal charter was granted to Carreira da India, a trade organization, giving it the exclusive right to import spices to Europe. [Source: Jean-Philippe Vergne, Bloomberg, May 29, 2013 /*]

“At the beginning of the 17th century, other European powers entered the race to set up monopolies with the support of the Indies companies. This is how, in 1602, the United Provinces granted the Dutch East India Company a 21-year monopoly on trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. This led to the ruin of well-established merchants and triggered two reactions: Some companies stood up to monopolies by establishing a parallel, illicit trade route; others tried to take over, by force, areas controlled by a monopoly. /*\

Portuguese carracks unload cargo in Lisbon in 1593

“States considered both actions piracy. For example, pirate organizations operating in the late 17th and early 18th centuries supplied the island of Manhattan with slaves, circumventing the Royal African Company, which held a monopoly on the trade. The historian Marcus Rediker estimated that, at the beginning of the 18th century, incessant pirate attacks led to a crisis for the British Empire and threatened the stability of international trade. Admittedly, sea pirates weren’t motivated by some high-minded idea of free markets. Rather, they were independent merchants who had become outlaws as a result of the monopolistic practices of European states. And many resorted to violence after being deprived of their right to trade. /*\

In his treatise “The Free Sea,” the 17th-century legal scholar Hugo Grotius wrote that waters and navigation are “free” because the sea is a public good that doesn’t belong to anyone. Iberian and English sovereigns, however, claimed that the parts of an ocean that linked their territories could be legally appropriated. Grotius’s viewpoint eventually won. Freedom of the open seas — now more than 50 percent of all water surfaces on Earth — was achieved through a series of treaties, starting with the 1856 Declaration of Paris, which also abolished privateering. As the historian Anne Perotin-Dumon put it, to eliminate piracy, “trade monopoly had to be given up altogether.” /*\

Portuguese Sea Travel and Seamen

Portugal during Age of Discovery had a population of only a million or so, with a few thousand scattered around the world. The ships that left Lisbon harbor were sent off with salutes from trumpets and canons. Degredados (convicts with sentences commuted to exile) were the first people sent ashore.

Sea travel between China and the West was dictated by important wind and ocean currents, the most formidable of which was the monsoon which decided when shipa could travel from east to west and visa versa. Currents along the east African coast determined how far ships could travel and still make it back to Arabian ports in a single season. Portuguese ships carried Arab and African pilots.

The 24,000 mile roundtrip voyage between Lisbon and Goa took 18 months and only the captain, noblemen and officers had descent living conditions. Many of the mariners were desgredados. They slept in crowded decks that resembled those used by slaves, drank filthy water and ate the food was often rotten or spoiled. Thousands of mariners died from scurvy at sea and malaria on land. Many also died of dysentery and typhoid. "If you want to learn to pray, go to sea," went a Portuguese proverb. The only thing that made the journey worthwhile was that each man was allowed to bring back a duty-free "liberty chest” in which they were allowed to bring back all the spices they could to sell back home.” [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

Portuguese was the lingua franca in most of the coastal ports in Africa and Asia during the 16th century. Portuguese mariners took lovers all over their empire. The Portuguese captains encouraged their bachelor soldiers to get married to help stabilize the empire.

Sailors were enticed by tales of rivers of gold in Africa and gold, silver, pearls and precious stones in Asia. Sailors to the New World enjoyed telling stories about men who had no heads or heads that grew beneath their shoulders; Patagonians with a single large foot; Labodoreans with tails; 500-foot-long sea serpents; and mermaids and mermen that feasted on eyes, noses, fingers toes and sexual organs of blacks and Indians. Columbus wrote that he had a meeting with three Sirens. [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Discoverers"]

Portuguese Navigation Secrets

In order to preserve their monopoly on Asian trade the Portuguese kings demanded that the locations of the trading centers and the routes there be kept secret. "It is impossible to get a chart of the voyage" to India, an Italian agent wrote, "because the King has decreed the death penalty for anyone sending one abroad."

The Portuguese had to be especially careful because they hired foreigners such as Vespucci (Florentine Italian) and Colombus (Genoese Italian) to captain their vessels. In 1481 one Portuguese mariner petitioned King John II to exclude foreigner's particularly Genoese and Florentines because the routinely stole royal 'secrets as to Africa and the islands."

When Drake passed through the Straight of Magellan in 1578 he learned that South America was not connected to a "southern continent." The information from Magellan voyages had been kept secret for more than half a century. Sebastian Cabot (1476?-1557) had earlier tried to sell Magellan's "Secret of the Strait" to both Venice and England.

The Portuguese were good at keeping their secrets for a hundred years or so. Until the mid 16th century, mariners from other European countries had rely on 'ancient writers, casual overland travelers, occasional turncoat sailors, and spies." The age of secrecy was brought to an end with the widespread use of the printing press and the profits made from selling sea charts.

Some historians even suggest that Portuguese mariners beat Columbus to the new World but the kings were so worried about secrecy it was never recorded. "But," according to historian Samuel Eliot Morrison, "the only evidence of a Portuguese policy of secrecy with regard to the discovery of America is a lack of evidence of a Portuguese discovery of America.

Portuguese Shipwrecks from Their Golden Age

According to Archaeology magazine: The wreck of a 400-year-old Portuguese ship dating to the golden age of the European spice trade was located near the mouth of the Tagus River, 15 miles west of Lisbon. The ship appears to have sunk after returning from India with its cargo of valuable spices and Asian artifacts. During a preliminary survey of the wreck site, divers documented peppercorns, 9 bronze cannons engraved with the Portuguese coat of arms, Chinese porcelain from the Wanli period (1573–1620), and cowrie shells, which were often used as currency. [Source: Archaeology magazine, January-February 2019]

In 2008, miners in Namibia’s restricted Sperrgebiet diamond zone discovered the remains of a 16th-century Portuguese shipwreck, later identified as the Bom Jesus, lost in 1533. The find began with a copper ingot bearing the mark of financier Anton Fugger; excavations soon uncovered 22 tons of ingots along with cannons, muskets, swords, astrolabes, ivory, chain mail, and more than 2,000 gold coins—making it the oldest and richest shipwreck ever found on the sub-Saharan African coast. Human remains were minimal, suggesting many on board may have reached shore despite the harsh, isolated Namib Desert. . [Source: Roff Smith, National Geographic, October 2009 ***]

Historical research and surviving archival fragments helped reconstruct the ship’s story. The Bom Jesus had sailed from Lisbon in 1533 as part of the annual India fleet, bound for the spice ports of the Indian Ocean. A powerful storm near the Cape of Good Hope scattered the fleet, and the Bom Jesus vanished. Evidence suggests it was driven far north by winds and currents before striking rocks off present-day Namibia and breaking apart.

Although survival on this remote coast would have been difficult, archaeologists note the castaways might have reached the nearby Orange River or encountered local hunter-gatherers. The wreck itself has become invaluable to maritime archaeologists, offering rare insights into Portuguese nau design, navigation, and daily life aboard early India-route vessels—material normally lost due to centuries of looting and the destruction of Lisbon’s archives in the 1755 earthquake. The exceptional preservation, aided by heavy copper ingots anchoring the remains, has allowed researchers to document the site in detail, uncovering both the ship’s tragic end and its broader historical significance.

Saint Francis Xavier

The Spanish devoted more attention to Christianizing the local population than the Portuguese. St. Francis Xavier (1506-1552), the famous Spanish Jesuit missionary who devoted his life spreading Christianity in Asia, led the effort to convert local people on places controlled by the Portuguese. Known as the sainted Apostle of the Indies, he was born the youngest son of a Basque aristocrat. When he was 28 he helped found the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). He arrived in Goa 1542 and buried many dead Portuguese voyagers in India. He went to Japan in 1549 and helped Christianity advance there very quickly, especially in southern Japan. He also went to Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

Saint Francis Xavier died in 1552 at the age of 46 on the island Sancian off Guangdong province in China in present-day Macau in China during a proselytizing mission. After he died his body was packed in lime and shipped to Goa. His body was buried and later exhumed by Jesuits who cut off his right arm and sent it to the Pope as a gift. What remained of the body was placed in a gold and glass coffin in Goa cathedral.

The coffin was opened once a year, on St, Xavier's feast day on December 3rd, in Goa cathedral until 1755 when the king f Portugal took control of the body and decided it could not be seen without his orders and was displayed to the public once every ten years.

Now the well preserved body is on view anytime through windows on the side of the coffin. The body is shriveled and shrunken and the skull is visible from the head but the saint's red hair is still largely in place. The arm is a relic in the Vatican. In 1949 it went on a world tour, beginning in Japan.

Decline and End of the Portuguese Empire in Asia

Most of the profits—and most of the manpower—from Portugal’s East-West trade went into guarding the 15,000 miles of sea lanes between Goa and Lisbon. Even so, in one year alone, Portugal lost 300 ships to pirates. At homes farms and industries decayed. The government was forced to buy food and other necessities abroad. In the end , after mortgaging the country to the hilt, Portugal flooded the spice market and prices plummeted." [Source: Howard la Fay, National Geographic, October 1965].

Money from the empire ended up in the hands of Antwerp merchant syndicates and was wasted on Moroccan wars, dynastic marriages, and ostentatious displays. What sealed the decline were events not in Asia but in North Africa. Some 163 years after Prince Henry the Navigator attacked Ceuta, the Portuguese army headed by King Sebastion was defeated by the Moors. The Portuguese empire by this time had been large disassembled by the Dutch and British. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992] In 1578, Portugal entered a reckless war with Morocco in an efforts to annex it. The Portuguese set up a stronghold in Cuenta, on the northern coast of Africa just below the Straits of Gibraltar. Their ambitions to claim Morocco, however, came to an end during a four-hour Battle of the Three Kings on August 4, 1578 when a force of 25,000 Portuguese soldiers where crushed by a 50,000-strong Moorish force. According to legend only 50 men survived and hundreds of guitars littered the battle. Among the dead were the Portuguese monarch, King Sabastão, and his nobles. The Moroccan sultan died of a heart attack. The defeat spelled the end to the great Portuguese trading empire and allowed the Spanish, British, French and Dutch to take over the trade routes to Asia and the territories in the New World. The Portuguese managed to hold some fortresses on the Moroccan coast but they never again presented a threat to the Moroccans or any one else.

After the disastrous war in Morocco, Portugal's vast empire collapsed in a very short time. With its monarch dead and resources exhausted, Philip II of Spain absorbed Portugal in 1580 with only slight resistance. After Spain absorbed Portugal it took over some of their colonies. Naval and land battle between colonial powers in Southeast Asia in the 17th century gave the English and the Dutch East India Company the lucrative spice trade route the Portugese had established. Most Portuguese possessions were seized by the Dutch, who created a vast, though short-lived commercial empire in Brazil, the Antilles, Africa, India, Ceylon, Malacca, Indonesia and Taiwan and challenged Portuguese traders in China and Japan. [Source: World Almanac]

Portugal never reaped the vast amounts of gold of silver from its empire in Asia and Brazil like the Spaniards did in Peru and Mexico. It has been said Portugal's colonies drained more wealth than they produced. Today some inhabitants of India think that Vasco da Gama was an American businessman or an Indian king. [Source: Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1992]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025