ZHENG HE

Model of Zheng He's treasure ship

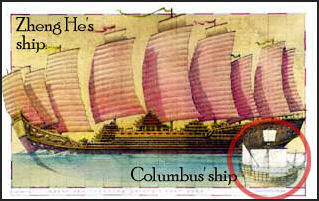

Zheng He (also known as Chêng Ho, Cheng Ho, Zheng Ho, and the Three-Jewel Eunuch) was a Chinese navigator and eunuch. He embarked from China with a huge fleet of ships and journeyed as far west as Africa, through what the Chinese called the Western seas, in 1433, sixty years before Columbus sailed to America and Vasco de Gama sailed around Africa to get to Asia. Zheng also explored India, Indonesia, Southeast Asia, and Arabia with about 75 times as many ships and men as Columbus took with him on his trans-Atlantic journey.

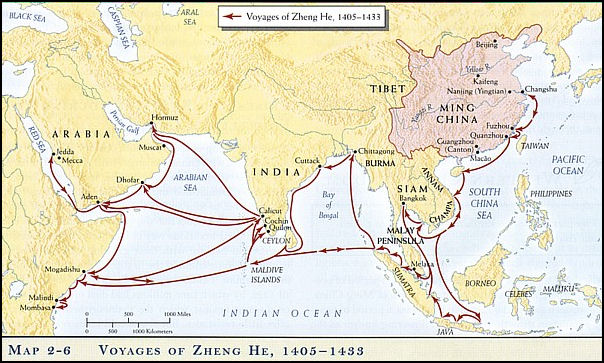

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “From 1405 until 1433, the Chinese imperial eunuch Zheng He led seven ocean expeditions for the Ming emperor that are unmatched in world history. These missions were astonishing as much for their distance as for their size: during the first ones, Zheng He traveled all the way from China to Southeast Asia and then on to India, all the way to major trading sites on India's southwest coast. In his fourth voyage, he traveled to the Persian Gulf. But for the three last voyages, Zheng went even further, all the way to the east coast of Africa. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Good Websites and Sources on the Silk Road: Silk Road Seattle washington.edu/silkroad ; Silk Road Foundation silk-road.com; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Silk Road Atlas depts.washington.edu ; Old World Trade Routes ciolek.com; Zheng He and Early Chinese Exploration : Wikipedia Chinese Exploration Wikipedia ; Le Monde Diplomatique mondediplo.com ; Zheng He Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Gavin Menzies’s 1421 1421.tv

See Separate Article ZHENG HE: THE GREAT CHINESE EUNUCH EXPLORER factsanddetails.com ; SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com; SILK ROAD EXPLORERS factsanddetails.com; EUROPEANS ON THE SILK ROAD AND EARLY CONTACTS AND TRADE BETWEEN CHINA AND EUROPE factsanddetails.com; MARCO POLO factsanddetails.com; IBN BATTUTA factsanddetails.com CHINESE EXPLORATION factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Amazon.com ; “When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405-1433" by Louise Levathes Amazon.com ; “Zheng He: China And the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405-1433" by Edward L. Dreyer Amazon.com

Zheng He's Expeditions

In the 3rd year of Yongle, under the order of Ming Chengzu Zhu Di, Zheng He and his assistant, Wang Jinghong, led a huge ship team composed of 62 treasured ships and more than 27,000 people,. They started from Liujia port, Suzhou, near Shanghai, and returned after more than two years. When arriving in each place, Zheng He exchanged porcelain, silk, copper and iron wares, gold and silver for local products.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

In the 3rd year of Yongle, under the order of Ming Chengzu Zhu Di, Zheng He and his assistant, Wang Jinghong, led a huge ship team composed of 62 treasured ships and more than 27,000 people,. They started from Liujia port, Suzhou, near Shanghai, and returned after more than two years. When arriving in each place, Zheng He exchanged porcelain, silk, copper and iron wares, gold and silver for local products.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

Sponsored by the Yongle Emperor to show the world the splendor of the Chinese empire, the seven expeditions led by Zheng He between 1405 and 1433 were by far the largest maritime expeditions the world had ever seen, and would see for the next five centuries. Not until World War I did there appear anything comparable. Overall He visited more than 30 countries and by some estimates covered 160,000 sea miles (about 300,000 kilometers).

Nayan Chanda wrote in the Far Eastern Economic Review, “On a crisp autumn morning in 1405 ... amid the sounds of drums and gongs, an extraordinary armada of giant ships unfurled its red silk sails and slowly made its way out [the Liujia harbour at the mouth of the Yangzi River] to the East China Sea. Under the command of a tall, ruddy-faced eunuch admiral, Zheng He, more than 300 vessels [some of which were four times the size European caravels, and armed with cannons and a slew of explosive devices], carrying a cornucopia of merchandise as well as 28,000 sailors, soldiers, traders, doctors and interpreters, set out on a voyage to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. It was the beginning of an epic series of voyages ... [that] dazzled maritime Asia and east Africa with the riches of the Middle Kingdom and the display of its political and military power. [Source: "Sailing into Oblivion," by Nayan Chanda, Far Eastern Economic Review, 162/36, September 9, 1999]

All seven expeditions led by Zheng began and ended in Nanjing and stopped at Qui Nhon in Champa (Vietnam), Surabaya in Indonesia, Palembang and Semudera on Sumatra, and the Malabar Coast in India, the source of much of the world's spices and the primary destination of all the voyages. There were side trips to present day Thailand, Bangladesh, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) eastern Malaysia, and the Maldives.

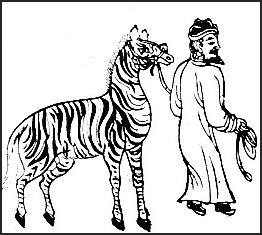

On his voyages to Africa, Zheng gave out gifts from the Chinese emperor, including gold, porcelain and silk. In return, he brought home ivory, myrrh, zebras and camels. But it was a giraffe that caused the biggest stir. The animal is known to have been a gift from the Sultan of Malindi, on Kenya's northern coast, but theories vary as to how exactly it got to China. One account suggests that the giraffe was taken from the ruler of Bengal” who himself had received it as a gift from the Sultan — and that it inspired Zheng to visit Kenya a few years later. [Source: Xan Rice, The Guardian July 25 2010]

Zheng He's Ships

Early European explorers to China were amazed by how much larger the Chinese ships were than their counterparts in the West. The smallest vessels were five-masted combat ships that measured 180 by 68 feet. The largest were colossal multi-storied ships, 400 feet long, 170 feet across at the beam, with nine masts, a 50,000 square foot main deck and a displacement of 3,000 tons. All the ships of Columbus and de Gama would have fit on the deck of Zheng He’s largest ship.

For centuries, historians thought stories of enormous Chinese ships had to be exaggerations. In 1962, workers unearthed a 36-foot-long wooden steering post in a trench in the Yangtze River in Nanjing. The post was large enough to connect to a rudder that covered an astonishing 452 square feet, large enough to steer Zheng He’s 400-foot-long treasure ship.

The vessels In Zheng He's fleet contained watertight compartments that prevented water in one part of the hull from flooding the whole ship — an advancement first developed by the Chinese in the Han period that would not appear in European vessels for several hundred after Zheng He. The compartments were created from bulkheads, a series of

Models of Zheng He's fleet

Crew,Provisions and Treasures on Zheng He's Ships

The largest expedition utilized a crew of 30,000 men and a fleet of 317 ships, including a 444-foot-long teak-wood treasury ship with nine masts, the largest wooden ship ever made; 370-foot, eight-masted “galloping horse ships,” the fastest boats in the fleet; 280-foot supply ships; 240-foot troop transports; 180-foot battle junks, a billet ship, patrol boats and 20 tankers to carry fresh water. The expedition was nothing less than a floating city that stretched across several kilometers of sea. By contrast to Columbus' expedition consisted for three ships with 90 men. The largest ship was 85 feet long. The largest ships in Vasco de Gama's fleet had four masts and were about 100 feet long.

The crew included sailors and mariners, seven grand eunuchs, hundreds of Ming officials, 180 physicians, geomacers, sail makers, blacksmiths, carpenters, tailors, cooks, merchants, accountants, interpreters that spoke Arabic and other languages, astrologers that predicted the weather, astronomers that studied the stars, pharmacologists that collected plants, ship repair specialists, and even protocol specialist that were responsible for organizing official receptions. To guide the massive ships, Chinese navigators used compasses and elaborate navigational charts with detailed compass bearings.

During the seven expeditions the treasure ships carried more than a million tons of Chinese silk, ceramics and copper coins and traded them for tropical species, gemstones, fragrant woods, animals, textiles and minerals. Among the things that the Chinese coveted most were medicinal herbs, incense, pepper, tropical hardwoods, peanuts, opium, bird’s nests, African ivory and Arabian horses. The Chinese were not interested in Europe, which only had wool and wine to offer — things the Chinese could produce for themselves. upright partitions that divided the ship's hold and prevented the spread of leakage or fire.

Zheng He's Voyages

Sea travel between China and the West was dictated by seasonal wind and ocean currents, the most important of which was the monsoons which decided when ships could travel from east to west and visa versa. Wind and ocean currents along the east African coast determined how far south ships could travel and still make it back to Arabian ports in a single season.

The amateur historian Gavin Menzies wrote a book called "1421", in which he asserts that Zheng He discovered America 70 years before Columbus and then continued across the Pacific back to China. Menzies bases his claim on Asian jade found in Aztec tombs, Chinese ideograms found on pre-Columbian pottery and a purported rendering of San Francisco Bay on a map made in 1507, which Menzies claimed was made with the help of an Italian who had hitched a ride of Zheng He’s fleet. While Menzies” book has sold well most historians reject his claims as frivolous at best.

The official records of Zheng He's voyages were destroyed after the death of Yongle Emperor. Most of what historian know about the voyages is based on three self- serving accounts by participants of the expeditions, the most notable of which is "The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shore", an account by a Chinese Muslim named Ma Huan, who served as an interpreter on at least three of the voyages.

Zheng He's Seven Expeditions

All seven expeditions led by Zheng began and ended in Nanjing and stopped at Qui Nhon in Champa (Vietnam), Surabaya in Indonesia, Palembang and Semudera on Sumatra, Malacca in Malaysia, Galle in Sri Lanka and the Malabar Coast in India, the source of much of the world’s spices and the primary destination of all the voyages. There were side trips to present day Thailand, Bangladesh, eastern Malaysia, and the Maldives.

The first expedition (1405-1407) included 317 ships and 27,870 men. It visited Java, Sumatra, Ceylon and western India. Altogether the voyage from China to India covered 6,000 miles at an average speed of 50 miles a day. Malacca became a home port for the fleet in Southeast Asia, opening the way for the immigration of millions of Chinese to the region over the following centuries.

The second expedition (1407-1409) returned ambassadors from Sumatra, India and other places who traveled to China on the first voyage. This voyage solidified trade links between China and countries around the Indian Ocean. The third expedition (1409-1411) was involved in a land battle in Sri Lanka and presented generous gifts to Buddhist temples. On Dodra Head, the southernmost point in Sri Lanka, Zheng left behind a stelae that paid respect to Buddha, Siva and Allah in Chinese, Tamil and Persian.

The forth expedition (1413-1415) made it as far west as the Persian Gulf. It was the first Chinese ship to travel beyond India across the Arabian Sea. An estimated 18 states sent tributes and envoys to China. The fifth expedition (1417-1419) stopped on the Arabian Peninsula and reached Africa (Kenya) for the first time. The sultan in Aden offered zebras, lions and ostriches as gifts.

The far reaching sixth expedition (1421-22) reached Zanzibar off the East African coast. The seventh expedition (1431-1433) embraced 37,000 men and 316 ships and traded with the African Swahili coat kingdoms of Malidi and Pate and made a side trip to Mecca. Since Zheng was a representative of the Ming Emperor and could not bow before the symbolic throne of a foreign ruler he was unable to make the trip to Mecca himself. Zheng died on this expedition.

On his voyages to Africa, Zheng gave out gifts from the Chinese emperor, including gold, porcelain and silk. In return, he brought home ivory, myrrh, zebras and camels. But it was a giraffe that caused the biggest stir. The animal is known to have been a gift from the Sultan of Malindi, on Kenya's northern coast, but theories vary as to how exactly it got to China. One account suggests that the giraffe was taken from the ruler of Bengal” who himself had received it as a gift from the Sultan — and that it inspired Zheng to visit Kenya a few years later. [Source: Xan Rice, The Guardian July 25 2010]

First Four of Zheng He’s Seven Voyages

The first expedition (1405-1407) included 317 ships, 317 ships including 62 “treasure ships” loaded with silks, porcelains and other precious gifts to trade for exotic products of the Indian Ocean, and 27,870 men including soldiers, merchants, civilians and clerks manned the ships. The nine-masted treasure ships were an astonishing size—said to be 140 meters (450 feet) long by 58 meters (185 feet) wide—twice the size of the first transatlantic steamer that appeared 400 years later. The fleet visited Java, Sumatra, Ceylon and western India. Altogether the voyage from China to India covered 6,000 miles at an average speed of 50 miles a day. Malacca became a home port for the fleet in Southeast Asia, opening the way for the immigration of millions of Chinese to the region over the following centuries.

The first expedition (1405-1407) included 317 ships, 317 ships including 62 “treasure ships” loaded with silks, porcelains and other precious gifts to trade for exotic products of the Indian Ocean, and 27,870 men including soldiers, merchants, civilians and clerks manned the ships. The nine-masted treasure ships were an astonishing size—said to be 140 meters (450 feet) long by 58 meters (185 feet) wide—twice the size of the first transatlantic steamer that appeared 400 years later. The fleet visited Java, Sumatra, Ceylon and western India. Altogether the voyage from China to India covered 6,000 miles at an average speed of 50 miles a day. Malacca became a home port for the fleet in Southeast Asia, opening the way for the immigration of millions of Chinese to the region over the following centuries.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In addition to thousands of sailors, builders and repairmen for the trip, there were soldiers, diplomatic specialists, medical personnel, astronomers, and scholars of foreign ways, especially Islam. The fleet stopped in Champa (central Vietnam) and Siam (today's Thailand) and then on to island Java, to points along the Straits of Malacca, and then proceeded to its main destination of Cochin and the kingdom of Calicut on the southwestern coast of India. On his return, Zheng He put down a pirate uprising in Sumatra, bringing the pirate chief, an overseas Chinese, back to Nanjing for punishment. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

The second expedition (1407-1409) took 68 ships to the court of Calicut to attend the inauguration of a new king. Zheng He organized this expedition but did not actually lead it in person. The second expedition returned ambassadors from Sumatra, India and other places who traveled to China on the first voyage. This voyage solidified trade links between China and countries around the Indian Ocean.

Zheng He did command the third voyage (1409-1411) with 48 large ships and 30,000 troops, visiting many of the same places as on the first voyage — including Champa, Java, Sumatra, Quilon, Cochin and Calicut — but also traveling to Malacca on the Malay peninsula and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The third expedition was involved in a land battle in Sri Lanka and presented generous gifts to Buddhist temples. On Dodra Head, the southernmost point in Sri Lanka, Zheng left behind a stelae that paid respect to Buddha, Siva and Allah in Chinese, Tamil and Persian. During the land battle between Zheng He’s forces and those of a small kingdom. Zheng put down the fighting, captured the king and brought him back to China where he was released by the emperor and returned home duly impressed.

The forth expedition (1413-1415) made it as far west as the Persian Gulf and Yemen. It was the first known Chinese ship to travel beyond India across the Arabian Sea. Zheng He commandeered his 63 ships and over 28,000 men to Hormuz on the Persian Gulf. Hormuz was a key link between the maritime and overland Silk Roads, linking the Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean and Arabaian Sea to overland routes to the major cities of Iran, Central Asia, Iraq. Damascus, which the Chinese dubs as “ning jiu li”, or “cohesive force”, was regarded as the western terminus of the overland Silk Road. The main chronicler of the voyages, the twenty-five year old Muslim translator Ma Huan, joined Zheng He on this trip. On the way, Zheng He stopped in Sumatra to fight on the side of a deposed sultan, bringing the usurper back to Nanjing for execution. An estimated 18 states sent tributes and envoys to China.

Last Three of Zheng He’s Seven Voyages

The fifth expedition (1417-1419) stopped on the Arabian Peninsula and reached Africa (Kenya) for the first time. The sultan in Aden offered zebras, lions and ostriches as gifts. The far reaching sixth expedition (1421-22) reached Zanzibar off the East African coast. The seventh expedition (1431-1433) embraced 37,000 men and 316 ships and traded with the African Swahili coat kingdoms of Malidi and Pate and made a side trip to Mecca. Since Zheng was a representative of the Ming Emperor and could not bow before the symbolic throne of a foreign ruler he was unable to make the trip to Mecca himself. Zheng died on this expedition.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The fifth voyage (1417-1419) was primarily a return trip for seventeen heads of state from South Asia. They had made their way to China after Zheng He's visits to their homelands in order to present their tribute at the Ming Court. On this trip Zheng He ventured even further, first to Aden at the mouth of the Red Sea, and then on to the east coast of Africa, stopping at the city states of Mogadishu and Brawa (in today's Somalia), and Malindi (in present day Kenya). He was frequently met with hostility but this was easily subdued. Many ambassadors from the countries visited came back to China with him. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“The sixth expedition (1421-1422) of 41 ships sailed to many of the previously visited Southeast Asian and Indian courts and stops in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the coast of Africa, principally in order to return nineteen ambassadors to their homelands. Zheng He returned to China after less than a year, having sent his fleet onward to pursue several separate itineraries, with some ships going perhaps as far south as Sofala in present day Mozambique.

“The seventh and final voyage (1431-33) was sent out by the Yongle emperor's successor, his grandson the Xuande emperor. This expedition had more than one hundred large ships and over 27,000 men, and it visited all the important ports in the South China Sea and Indian Ocean as well as Aden and Hormuz. One auxiliary voyage traveled up the Red Sea to Jidda, only a few hundred miles from the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. It was on the return trip in 1433 that Zheng He died and was buried at sea, although his official grave still stands in Nanjing, China. Nearly forgotten in China until recently, he was immortalized among Chinese communities abroad, particularly in Southeast Asia where to this day he is celebrated and revered as a god.

Zheng He’s Adventures

Zheng He's ships

In 1407, Zheng Ho” ships encountered the notorious Cantonese pirate Chen Zuyo in the Strait of Malacca. Operating out of Sumatra, Chen used his fleet of armed junks to control the straits. Almost all ships that passed through were either raided or forced to pay tribute. When Zheng arrived he demanded the pirate’s surrender. Chen agreed while secretly planning a surprise attack. Zheng had been alerted to the details of his plan and was ready. In the fierce battle Chen was captured, 5,000 of his men were killed and his fleet was destroyed. Chen was publically executed in Nanjing. The Chinese informant who gave up Chen was made the ruler of Palembang.

In Sri Lanka, Zheng Ho traded with the rulers there and may have taken the sacred tooth of Buddha back to China. The fleet’s only major land battle was in Sri Lanka where Hindu Tamils in the north and two rival Buddhist kingdoms in the south were fighting one another.

Zheng was drawn into the fray in Sri Lanka when his shore party was attacked by the forces of a rebel Buddhist leader. Acting quickly, Zheng lured the rebel troops into a hopeless attack on the fleet, leaving their capital open to an easy assault. The rebel Buddhist leader was easily defeated in 1411. Freed from the conflict with his Buddhist rival, the Sinhalese king Parakramabahu was able to defeat the Hindus in the north and solidify his rule over all of Sri Lanka.

Discoveries on Zheng He’s Voyages

Ma Huan wrote about sampling jack fruit with “morsels of yellow flesh, as big as hen’s eggs and tasting like honey” in Vietnam; discovering the “ten different uses” of the coconut in India;and seeing cockatoos, mynahs and parrots—“all of which can imitate human speech” — in Java. In Java he noted that “little boys of three years to old men of hundred years” carried knives. “If a man touches their head with his hand, or if there is a misunderstanding about money at a sale, or a battle of words when they are crazy with drunkenness, they at once pull out their knives and stab [each other].”

Ma described that while on shore leave the sailors did what sailors traditionally do: “if a woman is very intimate with one of our men, wine and food are provided, and they drink and sit and sleep together.” In Thailand he described men who put tin and gold balls in their foreskins, which “when the man walks around about, makes a tinkling sound...This is a most curios thing.”

Ma also wrote about marriage and funeral customs, languages and dialects, religion beliefs, architecture, commercial practices, science and technology and plants and animals.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Image Sources: Zheng He, wikipedia; 3) Eunuch boy, Brooklyn College; Zheng ship, Ohio State University; Zheng He expeditions, Dr. Robert Perrins, 1421; Zheng He tomb. China Beautiful website ; 1421; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021