AMBONESE

The Ambonese live on the island of Ambon and other islands in the Central Moluccas. The are also known as the Alifuru (interior of Ceram), Ambonese, Central Moluccans, the Moluccans, Orang Ambon and South Moluccans (exiles in the Netherlands). Maybe a million people live in the Central Moluccas. The population is pretty equally divided among Muslims and Christians. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Ambonese (pronounced AHM-bawn-eez) are very ethnically mixed. The Moluccas are near the traditional dividing line between Melanesian and Indonesians peoples and all sorts—Malays, Hindus, Chinese, Europeans, Arabs, other Asians—came to the islands for their spices. Genetic material and cultural traits from all these people have been left behind to varying degrees. ~

The strongest links to Melanesia are found among the Alifuru (Nua-ulu) in the interior of Seram (Ceram). While it's true that the people from Seram (Nusa Ina) have strong links to Melanesia, there are many other groups from other islands that are also predominantly Melanesian especially the Kei Islands and the Aru islands, but just Maluku Tenggara in general is very Melanesian. These people were headhunters until they were pacified by the Dutch before World War I and have a secret men’s society, the only such society in Indonesia and something normally associated with Melanesian cultures. In the days, severed heads were said to part of their marriage and coming of age ceremonies. Much of their old ways have been lost since they converted to Christianity. The culture of the Pasisir people who live in the coastal areas has been influenced much more by outsiders. ~

RELATED ARTICLES:

AMBONESE: LIFE, SOCIETY, FAMILY, FOOD factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

TANIMBARESE factsanddetails.com

NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

MALUKA (CENTRAL MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

BANDA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

MOLUCCAS: GEOGRAPHY, ISLANDS, WILDLIFE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

SPICES AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com;

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

Ambonese Identity and Where They Live

Adhering primarily to either Protestant Christianity or Islam, the Ambonese speak a local Malay dialect and reside in the Central Moluccas, a part of Indonesia's Maluku province. While often referred to as "Orang Ambon" collectively, this term is more accurately reserved for the coastal populations of Ambon-Lease and Seram. For outsiders, "Ambon"—encompassing the island, city, and people—often serves as a synonym for the entire Maluku region, leading to the label "Ambonese" (orang Ambon) being applied broadly to people from these diverse islands. In a stricter sense, the Ambonese ethnic group inhabits the islands of Ambon, Haruku, Saparua, and western Seram. [Source: Dieter Bartels, A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

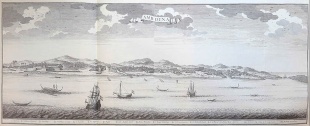

Ambon Island itself consists of two peninsulas, Hitu and Leitimur, joined by a narrow isthmus. The bay formed by these landmasses provides a sheltered harbor where the city of Ambon (Kota Ambon) was established. While fertile volcanic soil and high rainfall support agriculture, the terrain is steep, and surrounding coral reefs have suffered from destructive fishing and sand mining.

Even before the arrival of Europeans, spices drew traders and settlers to Ambon from Java and other Indonesian islands, as well as from India and the Arab world. Centuries of interaction and intermarriage produced a wide range of physical types, often varying sharply from village to village, and created an Ambonese culture that blended indigenous traditions with Hindu-Javanese, Arab, Portuguese, and Dutch influences. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Culturally, the Ambonese area is divided into two broad subcultures: the Alifuru culture of the interior peoples of Seram and the Pasisir culture of Ambon-Lease and the coastal zones of western Seram. The Alifuru were horticulturalists who practiced headhunting until they were pacified by the Dutch shortly before World War I. Most Pasisir Ambonese clans trace their origins to the interior of Seram, and Alifuru traditions form the foundation of Ambonese culture as a whole. Ironically, much of Alifuru culture was destroyed by zealous Christian missionaries from the Pasisir region, who failed to recognize that many practices they condemned as “pagan” in Seram were sacred to their own communities in Ambon-Lease. As a result, Christian villages on Ambon-Lease, converted some four centuries earlier, have preserved their cultural heritage better than the more recently converted mountain villages of Seram, which today often exist in cultural limbo and economic decline.

Ambonese Language

The Ambonese language belongs to the Central Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family and is therefore more distantly related to Bahasa Indonesia than are the Austronesian languages of Madagascar or the Philippines. It is closely related to dialects spoken in western Seram and, at a broader level, to Austronesian languages found in Timor. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Historically, a range of related Austronesian languages was spoken throughout the region, and many of these bahasa tanah (“languages of the land”) are still used in the interior of Seram and Buru. They also remain common in Muslim villages along the coast, but have survived in only a small number of coastal Christian communities. Most Christians today speak Ambonese Malay, a form of Sumatran Malay that developed as a regional lingua franca at least three centuries before the arrival of Europeans. Most Muslims are also fluent in Ambonese Malay. Increasingly, members of both religious communities also use the national language, Bahasa Indonesia, a standardized form of Malay used for formal communication.

At the end of the colonial period in 1950, Dutch was widely spoken in Kota Ambon. However, as the city has long attracted migrants from across the archipelago, a local variety of Malay—Bahasa Melayu Ambon—has remained the dominant everyday language. Today, this local Malay and Bahasa Indonesia are steadily displacing the region’s indigenous languages.

Ambonese Population

Data on the Ambonese is somewhat conflicting. There are around 1.590.000 Ambonese, according to Wikipedia, with 1.500.000 in Indonesia, mainly in Malaku, and 90,000 in the Netherlands. They live on Ambon island, southwest of Seram Island, which is part of the Moluccas, Java, Western New Guinea, and other regions of Indonesia. There are a significant immigrant populations of Ambonese in Jakarta and other large Indonesian cities. Those in the Netherlands are mostly the descendants of political exiles that arrived there in 1951. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia; Google AI]

According to the Christian group Joshua Project the Ambonese population in the early 2020s was 340,000. There were 258,331 Ambonese people living in Ambon according to the 2007 census. In 1980s the population of the Central Moluccas was estimated as 554,000, of which 112,000 resided in the provincial capital of Kota Ambon (Ambon City). The average population growth rate at that time was 2.5 percent per year.

Ambon Island's population is over 480,000 as of mid-2023, with around 354,000 Ambon City and 128,000 in surrounding districts in Central Maluku Regency (around 128,000). Based on historical data and studies of the region, those identifying as Ambonese make up approximately 79 percent of the population on Ambon Island, according to a report cited in a Brill publication.

The population of Ambon has grown rapidly; the two regencies, including Ambon City, held nearly 700,000 residents by 2005. The city of Ambon faces intense crowding, squeezing over 200,000 people into a narrow, four-square-kilometer strip between the coast and hills. Historically, the Ambonese were heavily represented in colonial military and bureaucracy, leading to significant populations settling in Makassar, Jakarta, and the Netherlands (around 40,000, largely former KNIL soldiers and their families).

Ambon in the Spice Islands Era

A year after capturing Malacca in 1511, the Portuguese dispatched an expedition led by António de Abreu to the fabled Spice Islands, landing at Hitu on the northern coast of Ambon Island. A fort was established there in 1522, though the Portuguese would eventually be expelled in 1575 by Hitu Muslims, aided by forces from Ternate. Before their removal, however, the first conversions to Catholicism took place in 1538, later expanding dramatically through the missionary work of St Francis Xavier in 1565; within three decades, some 50,000 converts were recorded. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Following their expulsion from Hitu, the Portuguese shifted to the southern coast of Ambon, where they built a fort that developed into Kota Ambon (modern Ambon City). In 1605, the Dutch captured the settlement in alliance with the Hitu Muslims, desecrated Catholic churches, and deported both European and mestizo Portuguese. The Dutch East India Company’s relentless drive to secure a spice monopoly soon followed, culminating in the massacre of English traders in 1623 and the hongi tochten—annual expeditions to locate and destroy clove trees and growers outside the monopoly. Clove cultivation was restricted to Ambon alone, excluding Ternate and Tidore. Ambonese men and vessels were compelled to take part in these raids, with villages granted land rights in proportion to their contribution.

The monopoly transformed Kota Ambon into a prosperous town, celebrated as the “Queen of the East,” said to rival or surpass Batavia and Manila. Local elites, adopting European dress and dance, shared in this wealth and influence, serving alongside Dutch officials on representative councils. From the eighteenth century onward, however, Ambon’s fortunes declined as coffee, tea, and sugar displaced spices in European markets. The city’s importance diminished further after the British occupation of Ambon between 1796 and 1802, which allowed clove cultivation to spread beyond Dutch-controlled areas.

Ambonese Under the Dutch and in Newly-Independent Indonesia

With the decline of the spice trade in the nineteenth century, Ambonese Muslims receded politically and economically, while Christian fortunes became increasingly tied to the Dutch. As trusted and loyal soldiers, Christians formed the backbone of the colonial army (KNIL), and as one of the best-educated groups in the Netherlands Indies, many also found employment in colonial administration and private enterprises far from their homeland. This pattern of out-migration continued after independence. Muslims, long excluded from education, have since narrowed the gap and now compete with Christians for employment. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The Ambonese played a central role in the expansion and maintenance of Dutch colonial power in the Indonesian archipelago. They made up roughly half of the colonial army (KNIL) and were heavily overrepresented in the bureaucracy. Known for their loyalty and discipline, Ambonese soldiers received higher pay and rations than most other recruits, earning them the Javanese epithets “dogs of the Dutch” and “black Dutchmen.” From the 1880s onward, growing numbers of Ambonese—by 1930 as many as 10 percent of the population—migrated to take up positions as soldiers, clerks, and minor professionals, roles for which Ambon’s advanced colonial-era education system prepared them. Christian Ambonese in particular felt more closely aligned with the Dutch than with other Indigenous groups. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

During World War II, Ambon’s strategic importance to both Japan and the Allies led to widespread destruction, especially in Kota Ambon. After the war, many Christian Ambonese, identifying more with the Dutch than with the emerging Indonesian state. Most Ambonese soldiers remained loyal to the Dutch and fought against Indonesian nationalists. Following the transfer of sovereignty in 1950, an independent Republic of the South Moluccas (RMS) was proclaimed but a guerrilla lasted until the capture of the RMS president in 1956. .

Fearing reprisals, about 4,000 Ambonese soldiers and their families were “temporarily” relocated to the Netherlands in 1951. Their continued commitment to the RMS ideal made return impossible. When hopes of returning to fight for the RMS faded, this community became a marginalized minority. Frustration in exile contributed to a series of terrorist acts, including dramatic train hijackings by some Moluccan youth in the 1970s. Only after these acts of terrorism did the Dutch government begin addressing the needs of the roughly 40,000-strong Moloccan community through bicultural education and employment programs. Throughout decades of exile, the community maintained strong separatist sentiments and resisted assimilation, though only in recent years has there been a limited move toward functional integration.

Modern History of the Ambonese

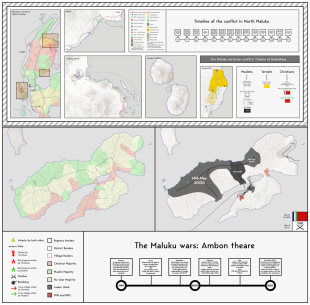

Under Indonesia’s New Order regime (1966–1998), government policies and the largely spontaneous influx of Muslim transmigrants—especially Bugis and Butonese from Sulawesi—destabilized Maluku’s long-standing demographic balance between Christians and Muslims, which had been nearly equal. Christian Ambonese, whose high educational attainment gave them dominance in the bureaucracy, resented Muslim newcomers’ growing control over the regional economy, even as they had long accepted the economic prominence of Christian Chinese communities. At the same time, Christians feared being displaced in government positions by a younger, better-educated Muslim population, while Muslims perceived continued Christian exclusion from power.

After the fall of Suharto, democratization and decentralization intensified these rivalries. Violence erupted in Kota Ambon and spread across Maluku and into North Maluku, evolving from localized clashes between Protestant Ambonese and Muslim migrants into widespread interreligious conflict involving Catholics and Muslims as well. News of the fighting triggered reactions nationwide: mass rallies in Jakarta called for jihad in Maluku, thousands of Laskar Jihad fighters entered the province, and sectarian riots broke out as far away as Lombok. The conflicts in Maluku and North Maluku killed an estimated 3,000 to 4,000 people and displaced between 123,000 and 370,000—making them the deadliest episodes of collective violence in Indonesia since the 1965–1966 massacres. Although a peace agreement in 2002 ended large-scale fighting, Kota Ambon remains largely segregated along religious lines, even as commerce and everyday interactions between Christians and Muslims have gradually resumed.

Ambonese Religion

According to the Christian group Joshua Project 70 percent of Ambonese are Christians, 10 to 50 percent of these being Protestant Evangelical. Other sources list the populations of both religions as roughly equal at 49 percent each. Few exclusively follow traditional animist beliefs but such beliefs have been incorporated into Ambonese Christianity and Islam. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Aside from God, whom both Christians and Muslims perceive as the same entity, ancestors play the most important role in Ambonese religion. In the traditional Ambonese belief system ancestors are called upon for blessings and invited to villages ceremonies and incorporated into concepts of salvation and the afterlife. There are also Christian and Islamic devils and spirits that cause illness and bring misfortune. At funerals there are often non-Christian and non-Muslim rituals to pacify the spirit of the deceased. Spirits and evil forces are linked with concepts of disease and health although generally Ambonese Western-style doctors before traditional healers.

To deter thieves, farmers erect matakau figures in their fields, invoking curses—such as a grasshopper symbolizing agonizing stomach pains, as if insects were crawling inside the body. Owners of young coconut trees may also ask the church council to pray for their protection, reinforcing the belief that theft will inevitably bring misfortune.

With the exception of five mixed settlements, the remaining 42 villages are exclusively Christian or Muslim. Islam was introduced to Hitu in northern Ambon by traders from Ternate and the north coast of Java well before the arrival of the Portuguese, who later brought Catholic missionaries, including St Francis Xavier. These early Catholic communities were dismantled by the Dutch, and large-scale conversion to Protestantism under the Dutch Reformed Church did not accelerate until the nineteenth century.

Muslim and Christian Ambonese

The Muslims and Christians in the Central Moluccas are surprisingly similar culturally. Their ideas about kinship and clan ties are similar, namely that villages or districts are made of several patrilineal clans led by a headman and clan descent is traced to a common ancestor. Marriage customs are also similar. Most are monogamous and in the past were arranged but today are largely love matches that follow two patterns: 1) formal request by the groom’s family, with the payment of a bride price; and 2) elopement. The latter is often preferred because it is way to avoid parental approval and the cost of a formal wedding. Divorce is rare among both Christians and Muslims. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

In the Pasisir region, Protestant Christianity and Islam dominate religious life, yet customary law (adat) continues to govern social relations in both communities. Islam expanded rapidly in the fifteenth century, but this process was checked by the arrival of the Portuguese in 1511, who converted much of the non-Muslim population to Roman Catholicism during their century of rule. The Dutch replaced them in 1605, transforming the Christian population into Calvinist Protestants and enforcing a spice monopoly despite strong resistance from both Muslims and Christians.

Ambonese Christians and Muslims have incorporated elements of ancestor worship and each other’s religions into their faiths and excluded members of other ethnic groups from their churches and mosques in an efforts to ensure ethnic harmony of the islands. The Ambonese even succeeded in syncretizing Christianity and Islam into the ethnic religion, Agama Nunusaku, Contrary to this effort has been efforts by conservatives in each faith to purify their religion and get rid of non-Christian and non-Muslim elements from the respective faiths.

Although both Christians and Muslims follow the religious calendars of their respective faiths, some ceremonies have taken on a distinct Ambonese meaning and flavor. This is especially true of life-cycle rituals. Traditional ceremonies such as the periodic renewal of the roof of the village council house and the cleansing of the village are no longer universally performed. ~

Religious Leaders in Ambon

The well-organized Moluccan Protestant Church (GPM) ordains both men and women. There is no regional organization that unites Muslims, who choose religious officials at the community level. In Muslim villages, the various offices are often still hereditary. Most villages still haveadat "priests" who deal with matters concerning the traditional belief system. Orang baruba, or healers, cure ailments that Western physicians cannot treat, such as those caused by sorcerers and evil spirits. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Indigenous beliefs coexist more easily with Islam than with Protestantism. Village halls (baileu), once accessible only with the permission of the resident spirits, contain a ritually powerful stone (batu pamali) that serves as an altar for sacrifices and offerings. In some communities, the heads of goats slaughtered in Islamic rituals are placed on this stone alongside skulls from earlier years. When timber is taken from the forest for a school, church, or the baileu itself, the head of a sacrificed goat may be hung from an old baileu pillar. Before the Dutch banned the practice, headhunting was central to ritual life, including marriage ceremonies where it formed part of the bride-price. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Alongside Muslim and Christian religious leaders, the mauweng acts as an intermediary between humans and ancestral spirits, especially in rituals intended to ensure agricultural success. The mauweng also functions as a healer, using divination to identify which ancestor has been offended and caused illness; modern medicine is regarded as effective only for treating symptoms.

After the abolition of the clove monopoly in 1863 undermined the economic and political power of village heads, Protestant ministers—typically outsiders—began to challenge their authority in Christian villages. Although the mauweng generally supported the village heads, the balance of influence has increasingly shifted in favor of the ministers.

Ambonese Ritual Life and Celebrations

The most important festival in villages is the Cuci Negeri, the annual village cleansing. The baileu, as well as every house and yard, is thoroughly cleaned. Failure to do so by one family would invite fatal illness or crop failure for the whole community. Village leaders give speeches to the ancestors who established the baileu, springs, and holy places, and pray to God for well-being. After the ceremonies, there is eating, drinking, and general merrymaking. However, in Soiya, scheduling the Cuci Negeri for the Friday before Christmas reduces the scale of the celebration. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Seven days after Idul Fitri, which marks the end of the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, young men in Mamala village hit each other with rattan brooms (made from the sharp central spines of pine fronds) until they draw blood. The wounds disappear after the application of a locally made coconut oil. ^

Funerals and Views About Death: Both Christians and Muslims bury their dead. After the funeral, one or more rites are performed to encourage the spirit of the deceased to leave its former home and travel to the abode of the dead. It is generally believed that the spirit remains on Earth until Judgment Day.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026