AMBONESE SOCIETY

Traditional Ambonese society has been democratic to a degree. Elevated status was largely confined to clans holding hereditary rights to the offices of village head and religious functionaries, while scholars and educated people also commanded considerable respect. In the postindependence era, however, the prestige of these positions has declined, and distinctions between “original” clans and those that settled later in a village have gradually weakened. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Within Ambonese society, the village is the largest and most significant organizational unit. Each village is linked directly and separately to the regional branches of the national government and functions as a largely autonomous entity, interacting with other villages much like independent ministates. Governance is carried out by a council of hereditary officeholders led by the village head (raja). Government directives requiring these councils to be opened to freely elected members, including non-Ambonese, have generally been met with strong resistance.

Villagers continue to prefer resolving internal disputes without recourse to the police or other state authorities. Fear of ancestral punishment—since the ancestors are regarded as the founders and guardians of adat (customary law)—remains the most powerful deterrent to social misconduct. Gossip, public shame, and the threat of ostracism are also effective mechanisms of social control. Historically, warfare was common, and inter-village fighting still occurs with some frequency, often involving injuries, deaths, and the destruction of property. Violence is also not uncommon in conflicts within villages.

Matrilineality is still found in the interior of West Ceram, whereas every village in the Pasisir region is made up of a number of patrilineal clans (mata rumah). Several clans form a soa, which was originally a distinct ward. Each soa has a headman (kepala soa), who represents its clans in the village council. Clan exogamy is no longer universally practiced due to the adoption of Christian or Muslim conventions regarding incest. Clan descent is traced to a common ancestor, typically the first man to arrive in the area in ancient times. The clans consist of a number of households (rumah tangga), which are the closest economic and emotional support units. A third important kin group is the famili, which consists of one's kindred on both the father's and mother's side. Like the clan, the famili provides support in crisis situations and helps defray costs on ritual occasions. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Recently, a shift toward bilaterality has emerged, particularly among Christians, The social emphasis on age is reflected by the ages of people indicated by most kinship terms. Cousin terms are similar to those in the Hawaiian system. The Hawaiian kinship system is the simplest classificatory system, grouping relatives by generation and gender only, with no distinction between maternal/paternal sides or siblings/cousins.

RELATED ARTICLES:

AMBONESE: HISTORY, IDENTITY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

TANIMBARESE factsanddetails.com

NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

MALUKA (CENTRAL MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

BANDA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

MOLUCCAS: GEOGRAPHY, ISLANDS, WILDLIFE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

SPICES AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com;

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

Traditional Ambonese Federations and Male Secret Societies

One of the most distinctive Melanesian-derived institutions in the region is a secret male society found on Seram and unique within the Indonesian archipelago. Before the arrival of the Dutch, related lineages originating in Seram were organized into soa (orkakehan), each led by an upu and supported by a military commander (malessi) and a religious specialist (mauweng). Under Ternatan dominance, these soa were grouped into federations known as uli. Ambonese society also adopted Javanese political terminology, using negeri for “state” or village and raja for village headmen.

Dutch rule dismantled the uli federations and replaced them with a system of autonomous villages governed by councils (saniri). At the top was the Saniri Rajapatih, composed of the village head and the soa leaders. Below it was the Saniri Negeri Lengkap, which included additional officials such as the tuan tanah (authority on customary land inheritance), the panglima (formerly a military leader), the kewang (forest guardians), and the marinyo (town crier). The broadest body, the Saniri Negeri Besar, encompassed all adult males but met only rarely, usually to elect a village head. Over time, the once-hereditary office of village head became largely ceremonial, with effective authority rotating among the soa leaders.

Although a distinction remains between a village’s “original inhabitants”—descendants of its founder who form the local elite—and later arrivals, Ambonese society is also characterized by strong translocal institutions. Every village belongs to one of two overarching factions, Patasiwa or Patalima, a division rooted in earlier political maneuvering by the Sultan of Ternate and associated with federations on opposite sides of the Mala River on Seram. Even more important is the institution of pela, a ritual alliance between two villages, often far apart and sometimes of different religions. These alliances are sealed through a blood oath, in which the partners draw blood, mix it with water, and drink it together. Pela obliges villages to aid one another in times of famine or war; a Muslim village may help finance its Christian partner’s church, and a Christian village may do the same for a Muslim partner’s mosque.

Ambonese Family

Among Ambonese, the nuclear family, which often has around ten members, forms the basic social unit. It is often enlarged to include aging grandparents, grandchildren, unmarried aunts and uncles, cousins, and foster children. Possibly under Muslim and Christian influence, kinship is organized along patrilineal lines, as reflected in the common practice of newly married couples residing with the groom’s family. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Household membership entails a shared responsibility for labor. Marital bonds are strong, and newlyweds generally establish an independent household not long after marriage, although residence remains predominantly patrilocal. Divorce is uncommon. Property is inherited by surviving sons, while unmarried daughters continue to draw their subsistence from the land of their natal families.

A typical household consists of parents, unmarried children, and married sons together with their wives and offspring. Every individual belongs to a patrilineal clan (rumah tau, matarumah, or fam), which bears a name and holds collective rights to political titles, land, and sacred stones and springs. Clan exogamy is mandatory. Women normally become members of their husband’s clan, except in cases where a woman is an only child, in which instance the husband joins her clan. Each rumah tau maintains a meeting house established by the clan founder, where weapons, textiles, and other heirlooms are kept under the hereditary guardianship of the clan leader.

Children are socialized by parents, older siblings, and other members of the household. Child-rearing is strongly authoritarian, and physical punishment is commonly employed once children move beyond early childhood. Socialization emphasizes obedience, family loyalty, and respect for elders, with collective values clearly taking precedence over individual autonomy.

Ambonese Marriage

Polygynous marriage was formerly known among the Alifuru, but today monogamy is universal among Christians and almost universal among Muslims as well. Although arranged marriages still occur, young people now usually choose their own partners. There are three recognized forms of marriage: marriage by formal proposal (kawin minta or kawin masuk minia), marriage by elopement (kawin lari or lari bini), and marriage in which the man moves into the woman’s household (kawin masuk or kawin manua). [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Kawin minia is regarded as the most honorable form and is more common among relatively prosperous families. In a kawin minta, a young man first informs his family of his chosen bride. His famili—all paternal and maternal relatives—then meets to discuss the bride-price, the wedding, and related arrangements. Once agreement is reached, a delegation approaches the young woman’s parents to request a date for the formal proposal. On that occasion, a spokesperson from the man’s kin presents his full name and lineage and negotiates the bride-price and other terms with the woman’s relatives.

The bride-price must be paid in full before a Christian or Muslim wedding can take place; otherwise, it is believed that the ancestors will be offended and may bring misfortune or death to the couple’s children. Delays in reaching agreement, often caused by the woman’s father’s reluctance, can postpone the religious ceremony and sometimes result in children being born out of wedlock, a situation strongly disapproved of by Christian authorities.

Marriage by elopement (kawin lari) is by far the most common form in the Moluccas, largely because it avoids parental disagreements and the high costs of a formal wedding. It may be chosen to prevent rejection or to spare a family the shame of a refused proposal. Although the woman’s kin generally disapprove of elopement, they may tacitly agree to it in advance as a way of reducing the bride-price without losing face. The groom’s brothers or friends assist in “abducting” the bride and removing her belongings. If the family is informed beforehand, the groom leaves a letter in a white envelope on the woman’s bed, explaining who has taken her and assuring them of her safety. After about a week in hiding, the woman is brought to the man’s house for the wedding rite and feast, during which she publicly distributes cigarettes and drinks, symbolizing her status as a married woman.

The third form, kawin masuk, when he groom joins his wife’s clan, generally occurs either to ensure the continuity of her lineage or because he cannot pay the bride-price. If the the grrom’s family cannot afford the bride-price he works for his in-laws in compensation, if his family opposes the match because of status differences, or if the bride is an only child and the groom must join her clan.

Ambonese Villages and Houses

Before the Muslim-Christian violence in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were some single religion villages in the Central Moluccas but most were mixed. Now the opposite tends to be more true. Originally located for defensive purposes on steep mountain ridges, many Ambonese villages relocates to the coast as a result of pressure by the Dutch.. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Most villages and towns have 200 to 600 people with separate Muslim and Christian communities organized around churches and mosques. Houses tend to be grouped closely together along a main road, though houses may also be separated by fenced yards. Each village includes a baileu (the village head's house) and small shops as well as a church or mosque, and religious leader’s house. Many houses have palms and fruit- and nut-bearing trees that provide food and shade.

Tightly clustered houses in coastal areas are often strung along one or more roads running parallel to the beach on a narrow strip of fairly flat land between the sea and mountains. The most prominent feature is either a large church or a mosque. Mostly along the beach there are rows of coconut palms. The land owned by each village is located beyond, in the mountains. ^^

Most people live in concrete houses with plaster walls and metal roofs. Some still live in traditional houses with dirts floors, thatch roofs and walls made from the stems of sago palm leaves. While traditional dwellings were built on wooden piles, contemporary Muslim and Christian houses are built on the ground. These houses have square floor plans and open verandas (dego-dego) in the front. The frame is made of sections of tree trunks or wooden beams, and the walls are made of plaited sago palm leaves. Since most houses lack windows, the steep roofs have holes in the corners to release smoke. Sometimes there is a room in the back that serves as a kitchen. Village leaders' houses are built in the European style with brick walls, windows, and separate rooms inside. ^

Ambonese Food and Clothes

The staple of the Ambonese diet is porridge made from sago starch, vegetables, taro, cassava, and fish. Sago palms grows abundantly in the local swamps. A tree between six and 15 years old can be cut down for food. The preparer beats the core of the tree to loosen the flour-rich fibers. The fibers are then washed and squeezed through a filter to obtain the starch, which is formed into squares called tuman. The tuman can be grilled or made into a thick porridge called pepeda. Much of the rice eaten on Ambon Island is imported. Rice supplements sago palm starch, but does not replace it. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Other available foods all year round are bananas and papayas. Freshly grilled fish is served with colo-colo, a sauce made from chopped onions, chili peppers, and tomatoes. Kohu-kohu is a pungent salad made with shredded tuna, bean sprouts, onions, and cabbage. Laor, seaworms that come to shore to breed in March and April, are also eaten with a spice mixture. Although not announced on local menus, black dog is also cooked. From the sap of the lontar palm, locals distill a wine called moke. ^

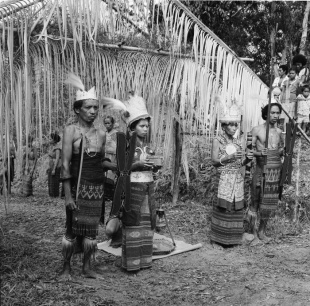

Most men wear modern European-style clothing and wear traditional short jackets and black trousers only on special occasions. Women wear thin blouses or small-patterned sarongs. Older women typically wear black, while younger women wear brightly colored knee-length cotton dresses. Traditional Ambonese clothing preserves elements of 16th-century Portuguese fashion.

Ambonese Life

Children's toys include hoops made from old bicycle wheels and stilts made from palm trunks. Billiards is a popular pastime. Children play in the early evening because it is too hot in the afternoon. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Transportation: In Kota Ambon, buses and becak pedicabs are the most common means of transportation. The city has more than 2,000 becak, which are divided into three color-coded groups (red, white, and yellow) because not all of them can share the streets at the same time. The patakora from Ternate is regarded as the best of the local boat types. Large boats, such as jungku and orambi, transport merchandise to Kota Ambon.

Health Care: Illness is attributed to natural causes, ancestral punishment, and evil forces. Home remedies are used for less serious illnesses. Typically, Western-style physicians are consulted first, and traditional healers are visited if a cure is not found or if a physician advises it. ~

Education: Since the 19th century, when Christian missionaries established schools, Ambon has had one of the highest levels of education in the archipelago. This has enabled many Ambonese to migrate to other parts of the country for office work. In 2005, the level of literacy in the Maluku province was 96.16 percent, which is very high by Indonesian national standards and comparable to or superior to provinces with much higher GDPs per capita.

Ambonese Music and Dance

Ambonese like to sing and dance. Traditional dances like the “cakalele” (war dance) are still performed as are European dances that date back to the Dutch and even Portuguese periods that have long been forgotten in their home countries. Singing is an important element of festivals and social occasions, especially among Christians who do a lot choir singing in their churches. Many musical groups and pop stars in Indonesia are of Christian-Ambonese origin. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

The Ambonese have a rich musical folklore that has absorbed many European elements. Examples include the Ambonese quadrille (katreji) and the songs of the lagoon, which are accompanied by a violin and lap steel guitar. Traditional instruments include 12 gongs, a bamboo flute, a xylophone, an Aeolian harp, a single-membrane drum called a tifa, and a ukulele. The ukulele is part of the kroncong ensemble, a sentimental musical style derived from Portugal, one of whose cradles was Ambon. Orchestras of bamboo flutes open church services. Famous dances include the lenso and the cakalele, a war dance. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Ambonese are famous throughout Indonesia for their Western-style singing. Local Ambonese songs and singers are popular nationwide. Many of Indonesia's leading pop stars and musical groups are of Christian-Ambonese origin. In the Netherlands, Ambonese soloists and bands have gained recognition beyond the boundaries of the exile community.

Ambonese Folklore

A Christianized origin myth traces the first humans to the slopes of Mount Nunusaku in western Seram. There, they lived in abundance until a Fall reminiscent of Genesis, after which they dispersed to Ambon and other islands. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The brief British occupation during the Napoleonic Wars produced two celebrated local heroes whose resistance to the restoration of Dutch rule won them national recognition. Thomas Matulessy, better known as Pattimura, had served the British as a sergeant major before leading a rebellion against the returning Dutch. Martha Christina Tiahahu, the daughter of another rebel leader, carried on her father’s struggle after his death and, when captured, refused to betray her comrades; she ultimately starved herself en route to exile in Java. ^^

A well-known ghost story centers on the village of Soya Atas. According to legend, the daughter of the village head fell in love with a Dutch official and, defying her father’s wishes, drowned herself. Her spirit is said to abduct foreign men or small children, who vanish and are later found dead or severely traumatized. Only water given by the current village head can restore them. ^^

Ambonese Agriculture

Most Ambonese are farmers, fishermen or plantation workers. Yams, cassava and taro are grown in family gardens (kebon), Sago is grown in swampy areas. Relatively little rice is grown. Rice, a high-prestige staple, is grown almost entirely by Javanese transmigrants on Seram, yet local production falls far short of demand and most rice must be imported. Cloves and nutmeg are the major cash crops, followed by copra. These are most produced mostly on plantations. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In mixed perennial gardens (dusun), farmers cultivate fruit and nut trees alongside cloves and nutmeg, the principal cash crops, followed by copra. Fish—caught individually or communally—is the main source of protein, supplemented by domestic animals and small game. Hunting for deer, wild boar, and birds—often with traps that can endanger people—supplements diets. Fishing is done with hooks, harpoons, and nets. ^^

Many Ambonese practice slash-and-burn cultivation of tubers and peanuts. Potatoes, introduced by the Dutch, remain a minor crop grown on mountain slopes. Other crops include coffee, sugarcane, cassava, maize, and a wide range of fruits such as bananas, mangoes, mangosteen, durian, and medicinal gandaria. Coconut production meets regional needs. Tobacco is grown for household use under the eaves of houses, where rainwater aids growth and leaves are dried on the roof. Although the Dutch clove monopoly no longer restricts cultivation to Ambon, cloves are still widely grown, requiring little labor but yielding good profits, especially for the kretek cigarette industry. Surplus produce is sold to cover taxes, school fees, and other necessities. ^^

Land Tenure: . Population growth has intensified land pressure on Ambon-Lease, where unclear boundaries frequently spark intra- and intervillage disputes that can turn violent. Village land is divided into communal forest (ewang) and cultivated dusun. Forest land is used jointly, while dusun is allocated among clans, which hold usufruct rights; ownership remains vested in the village and land reverts for redistribution if a clan dies out. Indonesian land laws increasingly permit private ownership and sale, and much land has recently been purchased by nonvillagers, especially Chinese. Rising land scarcity has prompted organized and spontaneous migration from Ambon-Lease to Seram, where land is more abundant, while government appropriation of Seramese land for Javanese transmigrants has generated growing tension. ^^

Ambonese Work, Crafts and Economic Activity

"Paintings," usually intricate still lifes of flowers, are fashioned from thin slices of mother of pearl. Large models of boats made entirely of cloves and wire are popular souvenirs. Embroidered bajus kurung (long shirts) are also produced. Woodcarvings and ikat cloth, which is tie-dyed, are generally sourced from the more traditional Tanimbar Islands to the southeast. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Few village specialists exist, and handicrafts are rare. Only two villages produce low-grade pottery and one practices metallurgy. Manual labor is generally despised, particularly among Christians, and both men and women prefer white-collar employment as ministers, teachers, administrators, or clerks. Muslims also engage in trade, but most industrial and commercial activities are dominated by Chinese entrepreneurs, some Arabs, and Muslim migrants from elsewhere in Indonesia. A sizable Butonese minority performs much of the low-level labor. Commercial fishing and logging, mainly on Seram, are carried out largely by foreign firms, usually Japanese, sometimes in partnership with local enterprises. ~

Some villages operate cooperatives or small shops, and Muslim peddlers visit Christian villages. Markets are concentrated in Ambon City and a few regional centers, where women sell garden produce or supply established traders. Men are regarded as providers and undertake riskier tasks such as fishing and hunting, as well as heavy work in horticulture and in building houses and boats. Women manage the household, assist in gardening and near-shore fishing, and handle most trading. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026