HISTORY OF THE MOLUCCAS

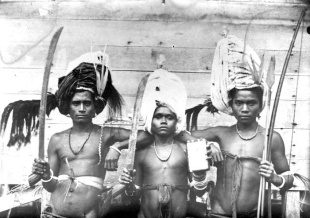

The Moluccas occupies a cultural and racial crossroads between Indonesia and Melanesia. Around 40,000 years ago, the first humans settled the Moluccas, sharing ancestry with those who populated Melanesia and Australia. Beginning 4,500 years ago, Austronesian-speaking seafarers from Sulawesi, and originally from Taiwan, arrived, creating the modern ethnic mixture of the present-day Moluccans. Moluccans have a long history of trade and seafaring, resulting in a high degree of mixed ancestry. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

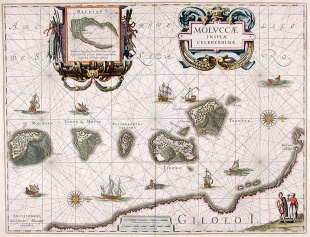

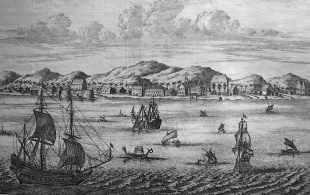

During the age of exploration and the colonial period that followed, the Portuguese, British French, Spanish and Dutch fought for control of the Moluccas, with the Dutch winning out in the end. The Moluccas were first visited by the Portuguese around 1512 and subsequently colonized by them, with a major trading center established at Ternate. Magellan's crew visited the Moluccas after Magellan was killed in the Philippines and loaded up on spices to take back to Europe. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th edition]

The Dutch arrived in 1599. and took over the Moluccas in the 17th century Although the British briefly gained control on two occasions, the islands passed permanently to the Dutch in the early 19th century. The Dutch established a monopoly on the clove and nutmeg trade from the Moluccas and made vast profits selling nutmeg, mace, cloves and other spices. In the late 18th century, a French missionary smuggled nutmeg seedlings out of the Dutch East Indies and they were replanted in Madagascar, Mauritius and Zanzibar. With this, the Dutch spice monopoly was broken and the Moluccas were largely forgotten.

After Indonesian independence, local separatists proclaimed the Republic of the South Moluccas, but the movement was suppressed. Separatist sentiment reemerged following the fall of President Suharto in 1998. In more recent years, the islands have experienced episodes of Muslim–Christian communal violence. In the late 1990s there was violence between Muslim and Christians that left scores dead. Muslims and Christian had traditionally gotten along; the trouble was stirred up by jihadists from outside the Moluccas.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MOLUCCAS: GEOGRAPHY, ISLANDS, WILDLIFE factsanddetails.com

SPICES AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com;

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

PEOPLE OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: HISTORY, IDENTITY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: LIFE, SOCIETY, FAMILY, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

TANIMBARESE factsanddetails.com

NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

MALUKA (CENTRAL MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

BANDA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

Sultans on Ternate and Tidore That Controlled the Spice Trade

The kings in places like Ternate, Tidore and Bacan controlled much of the spice trade and possessed Kora-kora, powerful fleets, equipped with war canoes that roamed the seas of Sulawesi and Papua in their golden days. The kings were wealthy from spices, especially cloves. Cloves and spices were very expensive they helped preserve food at a time when there no refrigerators and were used as medicines.

.For a long time the spice trade was controlled by north Moloccan sultanates, name Ternate, founded in 1257, and Tidore, founded in 1109. Both were based on small islands and often fought among themselves. Their most valuable crop was cloves. Protecting their kingdoms were fleets of kora-kora , war canoes manned by over 100 rowers. The sultans relied on Malay, Arab and Javanese merchants to distribute their goods.

Nutmeg takes very little effort to grow. Life was good and easy the islanders that raised it. They had do little but watch the nutmeg grow, collect it from trees and take out the nuts and trade them for food, cloth and all the things they needed with Chinese, Malay, Arab and Bugi spice traders. The was competition between Muslims and Chinese over control of the Indonesian spice trade.

Ternate and Tidore islands were the home of powerful rival Muslim sultanates in pre-European times. Their influence at one time extended to the Philippines, Sulawesi and New Guinea. They were the two most powerful of the four kingdoms that controlled the clove trade until the arrival of Europeans in the 16th century. They held their own in battles against the Portugese and Spanish in the 1500s, but were eventually defeated by the Dutch and came under colonial rule.

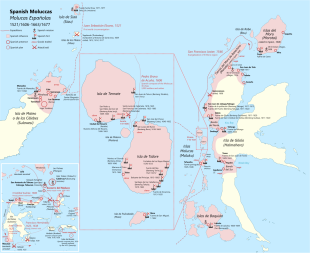

Arrival of the Portuguese in the Moluccas

After Afonso de Albuquerque (ca. 1460–1515), governor of Portuguese India, captured Malacca in 1511, he promptly dispatched three ships to the Moluccas. As a result, by 1512 the peoples of Banda, Ambon, and Ternate had already encountered the Portuguese.At the same time, Spain also turned its attention to the Moluccas. In 1521, two Spanish ships reached Tidore via the Pacific. The Tidorese welcomed the Spaniards, fearing that Ternate, allied with the Portuguese, would monopolize the clove trade. Although the Spanish presence was brief, the possibility of a Tidorese–Spanish alliance alarmed both the Ternatans and the Portuguese. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Partly in response to this perceived threat, the Portuguese constructed a fortress in Ternate in 1522. In later years they established additional trading posts and forts elsewhere in the Moluccas, but until 1575 all remained subordinate to the main stronghold in Ternate.

Portuguese policy in the Moluccas pursued two interconnected goals. First, the Portuguese sought to secure large quantities of cloves, nutmeg, and mace for the crown while excluding as many competitors as possible. Second, they aimed to support Catholic missionary activity, particularly in regions where the spread of Islam might be curtailed. Fortifications served both objectives, functioning as commercial centers and as military bases that offered protection to local populations who converted to Christianity.

These ambitions were undermined by weak political, administrative, and military organization, chronic shortages of manpower and resources, and the great distance separating the Moluccas from Goa, the Portuguese headquarters in Asia. Commanders were appointed from Goa for three-year terms and were responsible for recruiting their own followers. Many who enlisted for service in the remote Moluccas were considered marginal figures within Portuguese Asian society. Once there, most sought personal enrichment through private trade, often at the expense of royal interests. Oversight from Goa proved largely ineffective.

Portuguese Impact on Ternate and Tidore

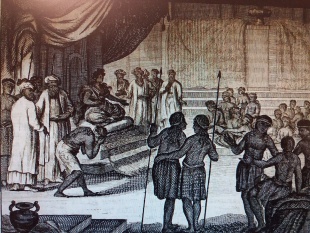

Unable to impose their authority by force alone, the Portuguese exploited existing divisions within Moluccan society. In Ternate, whenever Portuguese and Ternatan interests diverged, ambitious local elites were often willing to align with the Portuguese to advance their own standing. At the same time, the alliance strengthened Ternate’s political and military position relative to its rivals within the region. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Tidore and Jailolo attempted to counter Portuguese influence by aligning themselves with Spain, which briefly reappeared in the Moluccas between 1527 and 1534 and again in 1544–1545. These efforts proved largely ineffective, as Spain was unable to sustain a lasting presence. Backed by Portuguese support, Ternate ultimately crushed Jailolo, which was finally subdued in 1551 by combined Ternatan and Portuguese forces.

In Ambon, the Portuguese took advantage of tensions between the League of Five and the League of Nine. Initially, they maintained cordial relations with the Muslim villages of Hitu in the League of Five. During the 1530s, however, Portuguese actions alienated the Hituese, who then sought support from Muslim communities in Java and Ternate. In response, the Portuguese allied themselves with the pagan villages of the League of Nine, many of which converted to Christianity under Jesuit influence. Longstanding rivalry thus evolved into open conflict between Muslim and Christian factions. Confronted by growing pressure from Muslim Hitu, the Portuguese began building a fort on the Leitimor peninsula in 1575. This fort later became the nucleus of Ambon city, today the capital of the Moluccas.

Deep-seated conflicts of interest and Portuguese hostility toward Islam prevented lasting cooperation with their most important ally, Sultan Hairun of Ternate (1535–1570). In 1570 Hairun was assassinated on the orders of the Portuguese commander Diogo Lopes de Mesquita, who viewed him as an obstacle to Portuguese expansion. This act triggered a complete rupture. Thereafter, the Ternatans relentlessly attacked Portuguese positions, eventually forcing the surrender of the fortress in Ternate in December 1575. The Portuguese withdrew to Ambon, where construction of the Leitimor fort had just begun. From that point onward, Ambon became the principal European base of power in the Moluccas.

Portuguese Presence in the Moluccas

One of the first Portuguese expeditions to the Moluccas never returned to Malacca; instead, at the invitation of the ruler of Ternate, its crew settled on the island. Impressed by Portuguese technical knowledge, military skills, and weaponry, the Ternatans encouraged them to establish a permanent trading post in Ternate. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Some Portuguese never returned to Goa at all. Instead, they settled permanently in the Moluccas, forming families with local women or enslaved women brought from elsewhere. Their livelihoods depended partly on private trade, purchasing spices from local producers and selling them either to crown agents or to Asian merchants who offered better prices. Slaves worked gardens, fished, and cultivated spices, sustaining these households. These settled, married Portuguese men, known as casados, became the backbone of Portuguese society in the Moluccas, and some even served as advisers to local rulers.

The Portuguese never established a permanent trading post or fort in Banda. Nevertheless, Portuguese ships regularly—usually once a year—visited the islands to purchase nutmeg and mace, competing with other foreign traders. Following the Portuguese expulsion from Ternate, Sultan Gapi Baguna of Tidore (r. at least 1571–1599), fearing Ternatan dominance, invited the Portuguese to establish a military presence on his island. He hoped this would divert the clove trade from Ternate to Tidore. In 1578 the Portuguese built a fort in Tidore, thereby reestablishing a foothold in the North Moluccas. Nevertheless, they never regained the level of influence and power they had once enjoyed.

Dutch and the Spice Trade

The Dutch established a monopoly on the spice trade from the Moluccas . They gained control over the clove trade through an alliance with the sultan of Ternate in the Moluccas in 1607. Dutch occupation of the Bandas from 1609 to 1623 gave them control of the nutmeg trade. Dutch control of the region was fully realized when Melaku was captured from the Portuguese in 1641.

On the Banda Island, the Dutch tried to trade knives, woolen clothes and other things that the Banda islander didn’t need. The Dutch demanded that they be given a monopoly and found a few complaint chiefs that signed “contracts” promising them their desired monopoly. In the meantime the English had arrived in the area and they and the Dutch tried to battle and outmaneuver one another for control of the islands.

The Dutch could be quite ruthless when it suited their purposes. In the Bandas, one governor-general beheaded and quartered 44 local chiefs and displayed the remains in 1621 at a fort after Dutch “negotiators” were killed in a dispute over the placement of a fort on sacred site.

In what today is eastern Indonesia, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) with the help of indigenous allies fundamentally altered the terms of the traditional spice trade between 1610 and 1680 by forcibly limiting the number of nutmeg and clove trees, ruthlessly controlling the populations that grew and prepared the spices for the market, and aggressively using treaties and military means to establish VOC hegemony in the trade. One result of these policies, exacerbated by the late-seventeenth-century fall in the global demand for spices, was an overall decline in regional trade, an economic weakening that affected the VOC itself as well as indigenous states, and in many areas occasioned a withdrawal from commercial activity. [Source: Library of Congress]

See Separate Article DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

Dutch Government Control and Increased Missionary Activity of the Moluccas

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, the Moluccas were returned to the Dutch in 1817. Disillusionment with the restoration of Dutch authority soon led to rebellion in the Ambon Islands, and it took the Dutch six months to suppress the uprising.Under the new colonial administration, direct involvement in production and trade was no longer the primary concern. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

As the nineteenth century progressed, emphasis shifted toward orderly governance intended to facilitate private trade and commercial development. With the expansion of the colonial state, administration itself increasingly became an end. As a result, Dutch interest extended to previously neglected regions, including parts of Halmahera, Seram, and Buru, as well as the southern islands, areas that had never held economic value for the Dutch. Efforts were made to bring these regions fully under Dutch authority and regular colonial rule, a goal that was largely achieved in the twentieth century.

In the early nineteenth century, a clear break also occurred with the VOC legacy in matters of church, mission, and education. Whereas the VOC had shown little interest in missionary activity, missionaries returned to the Moluccas from 1814 onward, first under British protection and later under Dutch rule. This marked the first sustained missionary presence since the departure of the Portuguese in 1605.

In the North Moluccas, missionaries active in Halmahera in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries frequently criticized the harmful effects of Ternatan and Tidorese rule on local populations. They advocated reducing the power of autonomous principalities and strengthening direct colonial administration. This contributed to an accelerated dismantling of indigenous political authority. Between 1907 and 1910, the rulers of Ternate, Tidore, and Bacan were compelled to relinquish their formal independence, bringing these territories more tightly into the colonial state. This step formalized an earlier process and laid the groundwork for restructuring their autonomy according to colonial norms.

Impact of Education and Religion on the Moluccas

Another significant development was the gradual expansion of the educational system in the Central Moluccas during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Although the formal separation of church and school made education theoretically accessible to Muslims, it was overwhelmingly Ambonese Christians who benefited. As a result, the expansion of education deepened the social divide between Christian and Muslim communities in Ambon. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

As the colonial state’s demand for Indonesian officials increased and educational opportunities in Ambon expanded, growing numbers of Ambonese entered colonial government service. Others found employment with churches, missions, schools, health services, or private enterprises. Men with only elementary education could enlist in the colonial army, which after 1875 actively recruited Ambonese soldiers. The willingness of Christian Ambonese to serve in colonial and Dutch private institutions, both within and beyond the Moluccas, remained strong until the end of colonial rule. In this way, the Moluccas—and Ambon in particular—were transformed from a source of spices into a reservoir of colonial manpower.

Although parts of the pagan population of Halmahera converted to Christianity, educational provision in the North Moluccas did not extend beyond elementary schooling. Consequently, development there lagged far behind that of the Central Moluccas, and nationalist ideas failed to gain traction. The South Moluccas, with the exception of the Banda Islands, had long been of marginal importance and continued to occupy a peripheral position throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The prewar nationalist movement for Indonesian independence also touched Ambonese society. From the early 1920s onward, it attracted supporters among better-educated Ambonese living outside the islands. Most, however, still anticipated the continuation of colonial rule and sought primarily improved social opportunities within that framework. On the Ambon Islands themselves, village chiefs—both Christian and Muslim—remained conservative and wary of challenges to their authority. In cooperation with Dutch officials, they worked to suppress political activity at the village level.

Moluccan Independence Movement After World War II

The Dutch suffered a serious blow to their prestige when they were defeated by Japan in 1942. When the Dutch returned to the region in 1945, it appeared that the previous regime would be reinstated. Large numbers of Christian Ambonese once again entered the service of the Dutch colonial apparatus as officials and soldiers. ~[Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The end of colonial rule in 1949 caused few problems in the North and South Moluccas. The Central Moluccans, however, reacted differently. In Ambon, the transfer of power led to the proclamation of an independent Moluccan Republic in April 1950. However, the uprising received no support outside the Central Moluccas, and the Moluccan Republic, which was dominated by Ambonese Christians, was short-lived. From 1950 to 1951, the Indonesian army crushed the rebellion. However, hard-core rebels continued to fight a guerrilla war in Seram until 1965. ~

After the end of World War II in 1945 , many Christians remained loyal to the Dutch and fought on their side against Indonesia nationalists. After Indonesia achieved full independence in 1949, the Christians wanted to make the Moluccas independent of Indonesia because they worried they wouldn’t fare very well in a nation that was 90 percent Muslims. In 1950, the Republic of South Moluccas (RMS) was declared in Ambon. Within a few months Indonesian troops retook Bury and Seram but resistance endured in Ambon until the leader of the movement fled to the jungles of Seram, where the group held out until the mid 1960s.

Christians with ties to the Dutch colonial administration battled with Indonesian troops in an effort to secede but their effort failed. Out of fear or reprisals from the Indonesian government, a group of 12,000 diehard Christian nationalists were removed from the Moluccas by the Dutch and placed in a converted concentration camp in Holland with what they thought was a promise that they would be returned to an independent Moluccas. That never happened and their offspring still remain in Holland, feeling betrayed and resisting all attempts to be re-assimilated.

In 2007, a group of people entered an area where Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was presiding over a government ceremony during the 14th National Family Day event in Ambon, Maluku and performed a traditional dance called the cakalele and waved flags of the separatist South Maluku Republic (RMS). The incident was a major embarrassment to Yudhoyono’s government. A year later a court sentenced the leader of RMS to life. The RMS first emerged in the 1950s soon after Indonesia won its independence from Dutch colonial rule. The group, which was mostly Christian but had some Muslim members, was defeated militarily and its leadership fled to the Netherlands, where it briefly had a government-in-exile. It was largely forgotten until Maluku erupted in Muslim-Christian violence in 1999 that killed some 9,000 people. [Source: Jakarta Post]

Moluccan Terrorists in the Netherlands

In December 1975, a group of Moluccans terrorist seized a train with 24 hostages for 12 days in an incident called the "Murder on the Milk Train." In the end the Moluccans didn't get an independent homeland which is mainly what they were after but they did get a museum and increased pensions for aging Moluccan veterans.*

Time reported: Early last Tuesday morning, six men carrying machine guns, a pistol and a hunting rifle boarded a four-car electric "milk train" at the Dutch town of Assen. Shortly after it left Beilen, ten miles away, the terrorists stopped the train and seized the passengers as hostages. As police and Dutch soldiers ringed the captive train, another group of terrorists struck in Amsterdam, forcing their way into the Indonesian consulate and taking 41 more hostages, including 16 children. By week's end the terrorists had murdered three people aboard the train, and four more had been wounded in the raid on the consulate. [Source: Time, December 15, 1975 /]

“The perpetrators of last week's outrage—as well as their cause—were little known outside The Netherlands. The terrorists were Indonesians from the South Molucca islands in the Pacific Ocean, and they were demanding that the Dutch help them gain independence from the Jakarta regime. The kidnapings, and the subsequent cold-blooded murders, virtually paralyzed The Netherlands. While the Cabinet met in emergency sessions, television and radio stations suspended normal programming in favor of solemn music and news bulletins. /

“Third Day. The Moluccans aboard the captured train warned Dutch authorities that they would kill their passenger-hostages unless a plane was provided to take them to an undisclosed destination. To prove that they meant what they said, the terrorists first threw the body of the locomotive's engineer, who apparently had been killed when the train was seized, onto the tracks. Later, the body of a passenger was tossed out.

After nightfall, 14 of the 50-odd hostages managed to run to safety from the rear of the train. The kidnapers stood firm. On the third day of the siege, after a fruitless round of negotiations, another passenger, wearing a yellow shirt and a red tie, was brought to a door of the train. He was shot fatally in the neck and flung onto the railroad bed. Soldiers standing a few hundred yards away openly wept at the cruel sight. /

“Meanwhile, in Amsterdam, four people were injured—one of them by terrorist gunfire—when they escaped from a third-floor window at the Indonesian consulate. With police sharpshooters ringing the building, mediators negotiated the release of twelve children, but Dutch authorities refused to discuss the Moluccans' demands until all the children were freed. Justice Minister Andreas van Agt also declared that none of the terrorists would be given safe passage out of the country. At week's end it was clear that the Dutch were determined to play a waiting game with both groups of terrorists, in the hope of wearing down their resistance. /

“The twin acts of violence were not the first signs of South Moluccan anger. Just before a 1970 visit to The Netherlands by Indonesia's President Suharto, they attacked the Indonesian embassy in The Hague, killing a Dutch policeman. Last week's kidnapings came two days before the Dutch Appeals Court was to rule on prison sentences handed 16 South Moluccans who were implicated in a plot last April to kidnap Queen Juliana and other members of the Royal Family. They planned to storm the palace at Soestdijk after ramming the gates with an armored car. /

“The Moluccan headache is a heritage of the old days of empire. A chain of islands at the eastern end of the Indonesian archipelago, the Moluccas were once known as the Spice Islands, for their prized crops of cloves, nutmeg and mace. When The Netherlands gave up its East Indies colonies in 1949, a faction of Moluccans, mainly from the island of Amboina, fought against being absorbed into the Indonesian Republic. After Jakarta crushed an attempt to set up a South Moluccan Republic, some 12,000 islanders were allowed to settle in The Netherlands.

At the time, the Dutch held out hope for the eventual creation of a Moluccan state, but the government has long since abandoned the goal as unrealistic. The exiled islanders have not. Their numbers swollen by Dutch-born children, Moluccans in Holland today number around 35,000. The cause persists, even though some of the young Moluccan rebels have never seen the islands they kidnap and kill for.” /

In May and June 1977, 13 Moluccan separatists attacked a train and four of their accomplices took students and teachers at a school hostage. The separatists took 61 adults and 106 children as hostages and demanded the release of 21 Moluccan radicals in Dutch jails. The hostage crisis lasted three weeks and ended with a sunrise attack by Dutch marines with smoke bombs and submachine guns that left six terrorists and two hostages dead.

Violence In the Moluccas

Between late 1998 and 2002 some 5,000 people to 10,000 were killed in violence between Christians and Muslims in the historically peaceful Molucca islands. Some 500,000 people were forced to flee their homes.

People died in fires, mob attacks and clashes between rival gangs. Some of the dead were mutilated. Many were killed with homemade weapons, There were reports of men having their penises loped off and placed in their mouthes. It is widely believed that many of the incidents were deliberately incited by false rumors and carried by ordinary people riled up by gang leaders for political ends.

Building were set on fire with Molotov cocktails thrown by youths and with flaming arrows fired from mosque and churches. Entire Muslim and Christian villages were destroyed. Often the only thing that could stop the fighting were heavy rain storms. Much of the violence went on outside public and press scrutiny.

Christians initially had the upper hand. Most of the dead were Muslims in the early months of the clashes. Tables were turned in favor of the Muslims when they received help from Muslim fighters that came from Java and other places in Indonesia. Many belonged to Laskar Jihad.

See Separate Article CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIM-CHRISTIAN VIOLENCE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026