PEOPLE OF THE MOLUCCAS

The Moluccas have a long history of trade and seafaring, resulting in a high degree of mixed ancestry. Malay, Indian, Arab, Chinese, Portuguese, Bugis and Javanese are all present. Tribal communities of Ua-ulu mostly don’t wear their traditional clothes anymore. Ua-ulu men can be distinguished with red headscarves that they wear. It is said they were once headhunters.

Around 2000 B.C., Austronesian peoples added to the native Melanesian population. Melanesian features are strongest among the people of the Kei and Aru islands and the interior of Seram and Buru. Later added to this Austronesian-Melanesian mix were Indian and Arab influences. More recent arrivals include Bugis traders from Sulawesi and Javanese transmigrants. Over 130 languages were once spoken across the Moluccas. However, many have now switched to the Ternate and Ambonese creoles, which are the respective lingua francas of northern and southern Maluku.

The far-flung Southeast Moluccas region is a thinly inhabited. Protestant Christians make up more than half of the population, while the rest is about evenly split between Catholics and Muslims. The Northern Moluccas are the original "Spice Islands," sought out for millennia by foreigners for their cloves and nutmeg. Though strong island identities persist, the inhabitants of the northern Moluccas are united by their shared Islamic faith and "creole" culture, which is an amalgamation of various indigenous and foreign traits. The Tobelorese on the northern peninsula of Halmahera are Protestant Christians, and other pockets of Christianity exist elsewhere. Various "Alifuru" tribal groups in the Halmahera interior still adhere to animistic religions. Austronesian languages are or were spoken throughout the region, except on Ternate, Tidore, and northern Halmahera. There, languages are spoken that, together with those in the Bird's Head of West Irian, constitute the West Papuan phylum. Ternate-Malay is widespread, and Bahasa Indonesia, the national language, has become the official means of communication. Besides cultivating cloves, the main economic activities are horticulture, fishing, and forestry. ~ [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

RELATED ARTICLES:

AMBONESE: HISTORY, IDENTITY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: LIFE, SOCIETY, FAMILY, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

TANIMBARESE factsanddetails.com

NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

MALUKA (CENTRAL MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

BANDA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

MOLUCCAS: GEOGRAPHY, ISLANDS, WILDLIFE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

SPICES AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com;

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

Christians and Muslims in the Moluccas

The 2 million or so people in the Moluccas are divided roughly equally between Christians (which include Indonesians and Chinese) and Muslims. Until the beginning of 1999 the two groups lived in relative harmony with one another.

Christianity has a 500 year history in the Moluccas and dates back to when Europeans involved in the spice trade began arriving on the islands. Most the Christians are descendants of people who have lived in the Moluccas since Dutch colonial times. Christianity took hold here because so many Christian Europeans arrived here to make money from the spice trade.

Some Muslims are descendants of people who embraced Islam before the arrival of the Dutch. Many are descendants of Muslims from elsewhere in Indonesia that came to the Moluccas. Although it's true that people from other Indonesian islands brought their religion with them, Arab traders introduced Islam to the early inhabitants of the Moluccas. Many people are settlers or relatives of settlers who arrived relatively recently from other islands in Indonesia. A few are descendants of offspring of indigenous Malays and black slaves brought to work on the plantations by the Dutch.

The Christians have traditionally had close ties with the Dutch. After the decline of the spice industry they became especially close with the Dutch. They were among the most loyal and trusted and best-educated Indonesians, making up a large share of the Dutch colonial army. They were favored over the Muslims for positions in the colonial government and were the larger of the two groups in terms of population. After Indonesia became independent, the roles of Christians and Muslims were reversed and Muslims were favored over Christians for good jobs and other privileges. Muslims set up prosperous businesses while Christians were relegated to farming and fishing.

The Christians originally formed a majority on the Moluccas but their dominance was diluted in the 1960s and 70s when the Suharto government encouraged Muslims from other islands to move there. By 2000, the population was about 55 percent Muslim and 45 percent Christian. Even so Christians and Muslims lived in relative harmony. Intermarriage was even common in some places. But all that changed in 1997 and 1998 when the Indonesian economy collapsed and Suharto resigned and buried resentments and animosities came to the surface. Muslims and Christian were involved in a number of disputes over land and intervillage fighting was common, with resulting casualties and burning of property.

Moluccan Boat-Oriented Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Ambonese ceremonial string winder probably from Kisar Island. Made in the 19th-early 20th century from wood, it is 24.8 centimeters (9.8 inches) long. Eric Kjellgren wrote: Boats play a central role, both physically and symbolically, in the arts and cultures of the peoples of The Southeast Moluccas. The islands of this region are primarily small and relatively isolated, and boats and boat-building were, and in many cases remain, essential to fishing, trade, and, formerly, warfare.

Although the people of each island maintain a distinct cultural identity, the artistic traditions, cultural practices, and indigenous religions of the region are closely related. One of the region 's most distinctive art forms were ceremonial string winders, which were made and used on a number of islands, including Kisar, Dawera, Dawelor, and Babar. The central portion of the winders served as spools for ceremonial measuring cords, used in the construction of boats and houses; the carved finials depicted important ancestors. On Dawera and Dawelor, the cords were named after the belts women wore around the waist to secure their skirts. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Although built by men, boats are believed to be female in the indigenous cosmology, and the use of a "woman 's belt" to measure them was considered appropriate to their gender. After the keel of a boat had been laid, the chord in the string winder was used to determine the correct heights of the bow and stern beams. To begin construction of the hull, a woman ceremonially laid the first planks, called papan poma’i (sacred planks), on either side of the keel. As the men then assembled the boat, they added a single "male" component, the stern beam; the beam's incorporation into the boat symbolically represented the sexual union of male and female cosmic forces.

On Dawera and Dawelor, string winder chords were also used to plot the dimensions of houses, which were seen metaphorically as boats and whose sections were given nautical designations. As "boats," houses were female but, again like boats, also had a male component-in this case the mekamu’o’ (main post) — so that the two sexes were symbolically united. Like the interior of a boat, the house plot measured by the cord was considered to be "inboard" and symbolically represented the first female ancestor. When the dimensions for a house were measured, the fer/of was wound around a string winder whose finial depicted this founding ancestress.

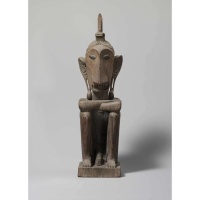

The images on many string winders are female or of indeterminate gender. However, a number of exampl es, including the present work, appear to depict male figures. The Metropolitan's string winder is similar to examples attributed to the island of Kisar, roughly two hundred miles west of Dawera and Dawelor, where the finials of string winders seem to portray both male and female subjects. Wearing earrings and peaked headgear, and seated on the ground with the legs drawn in and the elbows of the crossed arms resting on the knees, the finials of the Metropolitan and Kisar string winders closely resemble the larger ancestor images of the region, in particular the yene figures of the neighboring island of Leti. Although string winders on Kisar were likely employed in a manner similar to those of Dawera and Dawelor, it seems reasonable to suppose that, like yene figures, they portrayed recent ancestors of both sexes rather than a single ancient female progenitor.

Ancestor Figures from the Southeast Moluccas

In the southeast Moluccas ancestor images formed important links between the living and the dead. They were of two broad types: large figures depicting founding ancestors, often seated atop tall pillars and conspicuously displayed in specially constructed shrines in or near the village, and smaller figures depicting deceased family members, which were kept and used in the home. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Ancestor figures from the Southeast Moluccas aid in storytelling about ancestors and enable people to communicate with their deceased relatives. While most carvings follow the same conventions — the position of the arms and legs, elongated nose, large piercing eyes — they nevertheless represent a specific individual. Due to the position of the legs, one from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection from Leti is a male ancestor; male figures are shown with their legs bent and elbows resting on the knees, while female ancestors are typically shown with their legs crossed. The large size of the figure and the depiction of ear ornaments indicate the ancestor here was of high rank when he was alive. The protrusion emerging from the top of the head would customarily be wrapped in a red or white cloth, another indication of status. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

These carvings would have been commissioned by family members about five days after their relative passed away, and then kept in a secluded area of the house until they were needed. The carvings were brought out and used as a focal point to enable storytelling. Descendants would give the statue offerings of food and wine before consulting the ancestor embodied within to discuss matters of import or were asked to give support and advice before embarking on a significant endeavor. They would also act as mnemonics — similar to a photograph — to spark a memory so that an individual could tell a story about that ancestor, keeping their memory alive.

Speaking the name of the ancestor who is represented by this figure is potentially dangerous, for it is the act of naming that calls the spiritual entity into the carving and brings them into the present. In Southwest Maluku, the act of storytelling is what brings reality into being — a reality that must be harnessed and controlled by whoever named it. Symbols, metaphors, thematic devices, and proverbs are used throughout many artforms in the Malukus, including woven textiles and creation narratives. Each symbol (rou) is given its own name (ktunu) and with that name comes an entire story that takes shape as a narrated reality in the present.

The naming of this sculpture functions in the same way and it, too, would have been allocated a name. However, these carvings were largely destroyed or sold when much of Southwest Maluku converted to Christianity, and their names have not been spoken or passed down (rendering them inert and safe to view). Many sources refer to these sculptures as iene (or yene in Indonesian), which is a Letinese word that prohibits an action. In this case, it implies the name of this statue cannot be given. Letinese professor and linguist Aone van Engelenhoven suggests the name iene was possibly misunderstood by early collectors to be the name of this genre of carvings — a name that has been perpetuated in museum records. The term luli dera may be more applicable, for it refers more broadly to a male sacred entity, therefore avoiding any direct reference to the statue and the person it embodies.

Ambonese

The Ambonese live on the island of Ambon and other islands in the Central Moluccas. The are also known as the Alifuru (interior of Ceram), Ambonese, Central Moluccans, the Moluccans, Orang Ambon and South Moluccans (exiles in the Netherlands). Maybe a million people live in the Central Moluccas. The population is pretty equally divided among Muslims and Christians. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Ambonese are very ethnically mixed. The Moluccas are near the traditional dividing line between Melanesian and Indonesians peoples and all sorts—Malays, Hindus, Chinese, Europeans, Arabs, other Asians—came to the islands for their spices. Genetic material and cultural traits from all these people have been left behind to varying degrees. ~

The strongest links to Melanesia are found among the Alifuru (Nua-ulu) in the interior of Seram (Ceram). While it's true that the people from Seram (Nusa Ina) have strong links to Melanesia, there are many other groups from other islands that are also predominantly Melanesian especially the Kei Islands and the Aru islands, but just Maluku Tenggara in general is very Melanesian. These people were headhunters until they were pacified by the Dutch before World War I and have a secret men’s society, the only such society in Indonesia and something normally associated with Melanesian cultures. In the days, severed heads were said to part of their marriage and coming of age ceremonies. Much of their old ways have been lost since they converted to Christianity. The culture of the Pasisir people who live in the coastal areas has been influenced much more by outsiders. ~

See Separate Article: AMBONESE factsanddetails.com

Ternatan and Tidorese

The Ternatan and Tidorese live on two small islands in the North Moluccas: Ternate and Tidore. Also known as Orang Ternate, Orang Tidore, Suku Ternate and Suku Tidore, they distinguish themselves from the islanders around them by the use of the Ternatan and Tidorese languages and their link to historical kingdoms. The Ternatan and Tidorese are closely linked culturally but neither likes to be confused with the other.

There about 50,000 Ternatan and 100,000 Tidorese. About half of each live on their home islands. Most are subsistence farmers or fishermen. Only a few people are involved in commercial fishing. Staple foods include cassava, maize, bananas and taro. They are often eaten with dried and salted, smoke-dried or fresh fish. People rarely eat vegetables or meat. Most trade and commerce is handled by Chinese.

The Ternatan and Tidorese have a traditional of prearranged and child marriages to protect and enhance family status. Marriages offend end in divorce. Boys are generally spoiled and regarded as the pride of the family. They are often allowed to laze around and indulge themselves while girls are put to work. Most of their religious practice fall in line with proscribed tenets of Islam.

See Separate Article: TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

Tobelorese

The Tobelorese live on the northern peninsula of Halmahera island, which is north of the Moluccas and east of Sulawesi. Also known as the Orang Tobelo, Suku Tobelo, they speak a Papuan language and are subsistence farmers that raise rice, maize, cassava, bananas and vegetables and catch fish, There are about 85,000 of them, up from 20,000 in the 1980s, and nearly all Protestant Christians. In the past the Tobelorese were organized into four tribal villages headed by a single leader (kimelaha). Today, they are divided into several sub-ethnic groups namely, with the Dodinga, Boeng people and Kao being the main ones. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Wikipedia]

The Tobelo people were historically influenced by the Sultanate of Ternate and dominated several smaller interior groups. Most Tobelo live in mobile but primarily coastal settlements, occupying bamboo stilt houses with sago-palm roofing. They speak Tobelo (with several dialects), Indonesian, and Ternate, and are mainly Reformed Christians, with a Muslim minority and enduring traditional spiritual beliefs. Closely related forest-dwelling groups, known as the Togutil or O’Hongana Manyawa inhabit the interior of Halmahera (See Below).

The adoption of Christianity among forest Tobelo was slow and complex, gaining momentum only in the late 1980s through American missionary influence. Following severe Muslim–Christian violence in 1999–2001, a peace ceremony grounded in adat (customary law) helped restore social harmony and reassert ethnic identity over religious division.

Tobelo culture emphasizes song and dance, bilateral kinship, and patrilocal marriage, with elaborate wedding rituals highlighting women’s economic and symbolic roles. Traditional livelihoods include fishing, farming, and sago production, while diets center on fish and plant-based foods. Tobelo life and customs have also been documented in film and media, bringing wider attention to both coastal Tobelo and forest-dwelling Togutil communities.

Togutil (O'Hongana Manyawa) Hunter-Gatherers

The Togutil— also known as O'Hongana Manyawa (“people who live inside the forest”) and Inner Tobelo — live a semi-nomadic lifestyle in the jungles in the interior of Halmahera. They are closely related to the Tobelorese and have been described as “uncontacted” which is probably overstating their isolated existence. Traditionally nomadic hunter-gatherers reliant on sago, hunting, and small-scale shifting cultivation, many Togutil have increasingly interacted with coastal populations due to logging, mining, and government integration programs, with some settling in villages and earning income from forest products or wage labor.

The Togutil number roughly 1,500–3,000, with about 300–500 living largely isolated in Totodoku, Tukur-Tukur, Lolobata, Kobekulo, and Buli in the Aketajawe-Lolobata National Park, North Halmahera Regency, North Maluku, Indonesia.. Physically, they more closely resemble Malay populations than coastal Tobelo people, though their language is closely related to Tobelo and is sometimes classified as a dialect.

Some Togutil continue to wear traditional loincloths, although most of them have adopted modern clothing. They have traditionally lived in small communities along riverbanks, with simple houses made of wood and bamboo and roofed with palm leaves, often without walls or floors. Their traditional semi-nomadic, forest-based lifestyle centered on hunting wild boar, deer and other animals, as well as fishing and relying on sago palms as their main source of carbohydrates. They also harvest megapode eggs, resins, and antlers to sell to people from the coastal area. There is some horticulture, with bananas, cassava, sweet potatoes, papayas and sugar cane being common crops that can be found in their gardens. However, these gardens are not cultivated intensively owing to the Togutils' semi-nomadic lifestyle.

Although sometimes portrayed as violent or unsociable, ethnologists dispute these claims. Their worldview emphasizes forest conservation, captured in the saying “no forest, no life,” but this way of life is increasingly threatened by logging and nickel mining, which are degrading forest ecosystems and eroding cultural knowledge.

Historically, legends suggest the Togutil withdrew into the forest to avoid taxation, though there is no firm evidence for this. Missionary activity since the early 1980s has led many Togutil communities to convert to Christianity, resulting in the abandonment of earlier cosmological practices. Today, some Togutil remain isolated and resist outside intrusion, while others have integrated to varying degrees into surrounding society. They have also gained visibility through Indonesian media and recent footage opposing logging and mining on their ancestral lands.

See Separate Article: WEDA BAY — THE WORLDS’S LARGEST NICKEL MINE factsanddetails.com

Tanimbarese

In the southeastern part of Maluku Province lived more than 60,000 residents of the Tanimbar archipelago in the early 1990s. They resided in villages ranging in size from 150 to 2,500 inhabitants, but most villages numbered from 300 to 1,000. Nearly all residents spoke one of four related, but mutually unintelligible, languages. Because of an extended dry season, the forests were much less luxuriant than in some of the more northerly Maluku Islands, and the effects of over-intensive swidden cultivation of rice, cassava, and other root crops were visible in the interior. Many Tanimbarese also engaged in reef and deep-sea fishing and wild boar hunting. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Unlike the Weyewa, Toraja, or Dayak, the Tanimbarese do not maintain an opposition between their native culture and an officially recognized Christian culture. Following a Dutch military expedition in 1912, Catholic and Protestant missionaries converted all residents of their archipelago by the 1920s. However, the Tanimbarese tradition is preserved through intervillage and interhousehold marriage alliances. *

The Tanimbarese traditionally engaged in both a local system of ceremonial exchange and, for centuries, in a broader Indonesian commerce in which they traded copra, trepang, tortoise shell, and shark fins for gold, elephant tusks, textiles, and other valuables. In the twentieth century, however, Tanimbarese began to exchange their local products for more prosaic items such as tobacco, coffee, sugar, metal cooking pots, needles, clothing, and other domestic-use items. In the 1970s and 1980s, Chinese merchants thoroughly dominated this trade and consequently gained great influence in the local village economy. *

See Separate Article: TANIMBARESE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026