TANIMBARESE

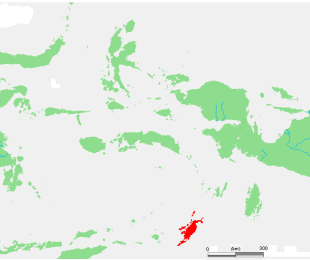

The Tanimbarese live in the remote Tanimbar archipelago In the southeastern part of Maluku Province. More than 60,000 residents lived on these islands in the early 1990s. They resided in villages ranging in size from 150 to 2,500 inhabitants, but most villages numbered from 300 to 1,000. Nearly all residents spoke one of four related, but mutually unintelligible, languages. Because of an extended dry season, the forests were much less luxuriant than in some of the more northerly Maluku Islands, and the effects of over-intensive swidden cultivation of rice, cassava, and other root crops were visible in the interior. Many Tanimbarese also engaged in reef and deep-sea fishing and wild boar hunting. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Tanimbarese are of mixed Austronesian and Melanesian ancestry. They are mostly Christians. Some are Muslims. Unlike the Weyewa, Toraja, or Dayak, the Tanimbarese do not maintain an opposition between their native culture and an officially recognized Christian culture. Following a Dutch military expedition in 1912, Catholic and Protestant missionaries converted all residents of their archipelago by the 1920s. However, the Tanimbarese tradition is preserved through intervillage and interhousehold marriage alliances. *

The Tanimbarese traditionally engaged in both a local system of ceremonial exchange and, for centuries, in a broader Indonesian commerce in which they traded copra, trepang, tortoise shell, and shark fins for gold, elephant tusks, textiles, and other valuables. In the twentieth century, however, Tanimbarese began to exchange their local products for more prosaic items such as tobacco, coffee, sugar, metal cooking pots, needles, clothing, and other domestic-use items. In the 1970s and 1980s, Chinese merchants thoroughly dominated this trade and consequently gained great influence in the local village economy. *

P. Boomgaard wrote in 2001: The villages of the Tanimbar Islands were often embroiled in long-standing feuds, something that was also quite common elsewhere in the archipelago. They also formed alliances with each other. Such alliances had to be renewed from time to time, for which purpose one village would visit the other every few years. A return visit would then be made the same number of years later. On these occasions, gifts were exchanged, and dancing, especially long and frequent, took place. On these occasions, the wealthy displayed their wealth by adorning themselves with all their jewelry. Note also the men's hats (made of two-tone cotton).

RELATED ARTICLES:

PEOPLE OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: HISTORY, IDENTITY, LANGUAGE, RELIGION factsanddetails.com

AMBONESE: LIFE, SOCIETY, FAMILY, FOOD factsanddetails.com

TERNATAN AND TIDORESE factsanddetails.com

NORTH MALUKA (NORTH MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

MALUKA (CENTRAL MOLUCCAS) factsanddetails.com

BANDA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

MOLUCCAS: GEOGRAPHY, ISLANDS, WILDLIFE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF THE MOLUCCAS factsanddetails.com

SPICES AND THE SPICE ISLANDS factsanddetails.com;

CLOVES, MACE AND NUTMEG: THE SPICE ISLANDS SPICES factsanddetails.com

DUTCH AND THE SPICE TRADE factsanddetails.com

Tanimbarese Villages and Houses

Tanimbarese orient themselves socially toward their villages and their houses. The unity of the village is represented as a stone boat. In ceremonial settings, such as indigenous dance, the rankings and statuses within the village are spoken of as a seating arrangement within this symbolic boat. Intervillage and interhouse rivalry, no longer expressed through headhunting and warfare, continue to be represented through complex ritual exchanges of valuables, marriage alliances, and competitive relations between the Catholic and Protestant churches (one or the other of which counts each Tanimbarese as a member). [Source: Library of Congress *]

Traditionally, Tanimbar houses were arranged in long rows, the most significant of which were known as lolat. A lolat referred to a row of houses defined by women who had been married out from those homes, particularly in earlier periods. Although these women left their natal houses to live with their husbands, they remained the most important ancestral figures of their houses of origin. In this way, a founding female ancestor defined an entire row of houses, as descent was traced through maternal bloodlines that linked multiple dwellings.[Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Architecturally, Tanimbar houses were raised on piers and constructed with relatively simple forms, dominated by steeply pitched roofs. While the exteriors were generally unadorned, houses traditionally contained valuable objects. In the past, lolat houses featured elaborately carved wooden altars depicting abstract human figures with outstretched arms. These finely detailed, almost lace-like carvings symbolized ancestral authority and were unique to Tanimbar. With the spread of Christianity, such altars were abandoned, and most surviving examples are now held in foreign museums.

Over time, cosmological beliefs have shifted and many traditional house rows have fallen into disrepair. Nevertheless, aspects of these distinctive architectural forms and complex marriage systems continue to endure, and ideas of social rank and lineage identity remain significant within Tanimbar society.

Tanimbarese ”Ultimate House Society”

In traditional Tanimbarese “ultimate house society.” patterns of marriage and descent on Tanimbar were complex and varied, making houses—rather than individuals—the primary markers of clan identity. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006 +]

Tanimbarese are affiliated with rahan (houses) that are important corporate units, responsible for making offerings to the ancestors, whose skulls were traditionally placed inside. Rahan are also responsible for the maintenance and distribution of heirloom property consisting of valuables and forest estates. Since Tanimbarese recognize a system of patrilineal descent, when a child is born they customarily ask: "Stranger or house master"? Since a male is destined to "sit" or "stay" in the house of his father, he is a "master of his house." If the baby is a girl, the child is destined to move between houses, and thus is a "stranger." [Source: Library of Congress *]

The question of which house the girl moves to, and what obligations and rights will go along with the move, is one of the most important questions in Tanimbarese society. There are certain "pathways" of marriage that young women from certain houses are expected to follow, particularly if these interclan alliances have lasted more than three generations. Only if certain valuables are properly received by her natal family, however, is a young woman fully incorporated into her husband's home. Otherwise, her children are regarded as a branch of her brother's lineage. *

These female bloodlines carried specific names, and only houses bearing such names could belong to a lolat row. House rows were ranked, with distinctions between greater and lesser lolat reflecting differences in social status. In the past, it was believed that these rows extended back through ancestral time and even into the next world, understood as the ultimate source of life. As a result, the house itself became the central focus of social and cosmological significance in Tanimbar society. +

Tanibarese Prow Board (Kora Ulu)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection contains a Prow Board (Kora ulu) from the Tanimbar Islands. Dated to the late 19th-early 20th century and made of wood, it is 152.4 centimeters (60 inches) long Eric Kjellgren wrote: The dramatic openwork prow boards, or kora ulu, of the Tanimbar archipelago, in Maluku Tenggara, are among the most visually complex forms of wood sculpture in Island Southeast Asia. Carved separately, kora ulu were attached as decorative accents to the prows of large seagoing vessels during important voyages (see fig. 70), but they were probably detached and stored when not in use. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In the past, and to some extent today, boats and voyaging played a central role in Tanimbarese culture and religion. Individuals and Island communities built their reputations through success in voyaging, from which the seafarers returned with precious foreign goods, such as gold valuables and ivory, to augment the village treasury. Until the early twentieth century, the spoils might also include the heads of slain enemies. In many Tanimbarese villages, boat-shaped altars, equipped with elaborately carved prow and stern boards of stone, formed the focus of social and religious gatherings. Tanimbarese shipwrights created a variety of watercraft, and the precise nature of the boats on which the kora ulu were employed is uncertain. However, it is probable that they adorned the large ceremonial boats used in trade, warfare, or the renewal of alliances between villages rather than more utilitarian vessels.

Boats and their accoutrements were laden with gender symbolism ; male and female elements complemented each other, ensuring supernatural balance and continuing fertility. The hull was considered female, its shape compared to a womb and likened to the new moon, which in Tanimbarese oral tradition is identified with a pregnant woman. The sail, rudder, oars, and towering prow and stern boards were male and, when united with the hull in preparation for an important journey, completed the vessel, making it ready for the voyage.

In former times, the vessels used on expeditions undertaken to renew the alliance and friendship between villages were often splendidly appointed. Carrying the most valuable gold ornaments of the voyagers' home village, and frequently adorned with flags and banners as well as, almost certainly, superbly carved prow and stern boards, these ceremonial vessels were compared to roosters displaying their resplendent plumage: Marni yaru o wean manut lamera o. Nalili vulun masa wean lera fanin o (Our boat, oh, is like a rooster, oh. It wears golden feathers like the rays of the sun, oh).

Whether a voyage was for alliance, trade, or war, before setting sail the kora ulu of ceremonial vessels were anointed with magical substances, prepared from roots and leaves, which invested the boat with lethal supernatural powers. The application of these substances was believed to render the vessel so supernaturally "hot" that the seas around it were said to boil, and the vessels of a ceremonial fleet were said to warn the unwary of their power with laluan (bow waves), which took the form of violent winds and severe thunderstorms. ' Cleaving the seas on the way to encounter friends or foes, the supernaturally charged boats were compared to fearsome sea snakes. 16 Rendered with a restless sense of highly charged movement, the intricate openwork compositions of Tanimbarese prow boards embody the aggressive energy of the vessels they once adorned. Surviving examples share a similar formal composition in which a zoomorphic figure-a rooster, dog, fish, or, as in the present work, a mythical reptilian creature, all animals symbolic of male status and aggression-at the base is surmounted by a field of sinuous openwork spirals.

The hallmark of Tanimbarese wood carving, this elaborate scrollwork is composed of a lively rhythmic pattern formed from single spirals (kilun etal) and S-shaped double spirals (kilun ila'a), whose curvilinear forms are reminiscent of the breaking of ocean waves or the tendrils of plants. The fantastic serpentlike creature on this work may depict the fearsome mythical sea snake to which the ceremonial vessel was likened. It is a chimera with a crocodile-like head whose jaws merge into the surrounding spirals and a long slender body ending in a fish 's tail. Its numerous legs resemble those of centipedes. Its jaws, slightly opened, reveal menacing teeth, a reminder that the intentions of those who rode within were not always peaceable.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated January 2026