EDO PERIOD ART

"During the Edo Period (1603-1868) both the subjects and styles of painting diversified significantly," wrote Smithsonian art curator Ann Yonemura, "as patronage broadened to include a newly affluent merchant class. Genre painting of contemporary urban life, new subjects and styles influenced by a limited importation of European art, and work by artists who based the lives on Chinese scholarly ideals flourished."

The Genroku era in the late 17th and early 18th century is sometimes regarded as the golden age of Japanese art, Kabuki plays, haiku poetry, and woodblock printing.

Edo period Japanese art is very popular worldwide. An Edo art touring exhibit drew 900,000 people in 2007, making it the most seen art show in the world that year.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; Art of the Edo Period metmuseum.org ; ArtLex.com on Edo Art artlex.com/ArtLex/e/edo ; Book: “Art of Edo Japan” by Christine Guth (Harry N. Abrams, 1996).

Samurai Armor, Weapons and Swords Gallery Samurai gallerysamurai.com ; Samurai Arms and Armor artsofthesamurai.com ; Kinokuniya Samurai Armor Shop www.kinokuniya.tv; Sokendo Samurai Armor Shop www.sokendo.net Armor from Clan Yama Kaminari yamakaminari.com ; Putting on Armor chiba-muse.or.jp

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Art: Artelino on Japanese Art artelino.com ; Web Japan web-japan.org/museum/paint.html ; Japanese Art Portal japaneseart.org ; ;Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Zeroland zeroland.co.nz ;Asia Society Virtual Tour asiasociety.org ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com

Art History Sites Art History Resources on the Web — Japan witcombe.sbc.edu ; Early Japanese Visual Arts wsu.edu:8080 ; Japanese Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Books: “History of Japanese Art” by Penelope Mason (Harry N. Abrams, 1993); “The People' Culture — from Kyoto to Edo” by Yoshida Mitsukuni (Cosmo Public Relations Corporation, Tokyo, 1986); “The Shaping of Daimyou Culture, 1185-1868" by Martin Collcut and Yoshiaki Shimizu (National Gallery of Art, 1988).

Art Museums in Japan Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Tokyo National Museum site tnm.go.jp ; Kyoto National Museum official site kyohaku.go.jp ; Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Nara National Museum narahaku.go.jp ; Kyoto University Museum inet.museum.kyoto-u.ac.jp ; National Museum of Art, Osaka nmao.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Tokyo tobunken.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Nara nabunken.go.jp/english ;Miho Museum near Kyoto miho.or.jp ; Photos danheller.com

Museums with Good Collections of Japanese Art Outside of Japan ; Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston mfa.org/collections ;British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art lacma.org/art ; Ruth and Sherman Lee Institute for Japanese Art Collection ucmercedlibrary.info

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAINTING Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE POTTERY AND LACQUERWARE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com; NINJAS IN JAPAN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; NINJA STEALTH, LIFESTYLE, WEAPONS AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com; ODA NOBUNAGA factsanddetails.com; HIDEYOSHI TOYOTOMI factsanddetails.com; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; LIFE IN THE EDO PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MARCO POLO, COLUMBUS AND THE FIRST EUROPEANS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE WEST DURING THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DECLINE OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO PERIOD ART: SAMURAI ART, URBAN ART, DECORATIVE AND GENRE PAINTING factsanddetails.com; UKIYO-E (JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINTS): MAKING AND COLLECTING IT, SEX AND VAN GOGH factsanddetails.com; UKIYO-E ARTISTS: SHARAKU, HOKUSAI, HIROSHIGE AND UTAGAWA factsanddetails.com

Daimyo, Samurai and Art in the Edo Period

The Edo Period was a time of relative peace. With no wars to fight and non-Japanese restricted from entering the country, the shoguns and daimyos (landed aristocrats) and samurai under them, concentrated their energies on the administration of the estates and pursuit of the art forms such as poetry, painting, architecture, No theater, calligraphy, flower arranging and the tea ceremony. With no foreigners to distract them, the daimyos and samurai were able to develop and refine art forms that were uniquely Japanese.

The emphasis on the arts was intended in part to keep the minds of military men off of military matters. "In daimyo Japan," Bennet Shiff wrote in Smithsonian magazine, "culture became synonymous with authority. Lords competed with one another in high art, tea, theater, poetry and the employment of artists, actors, poets, tea masters. Frequently they practiced one or two arts themselves. Not to participate was to be dropped out of what was meaningful and necessary. It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to name another society in world history in which art was so much a part of daily existence."

Early Edo Period Art

During the Momoyama and Edo periods Japanese art and society went through a series of changes illustrated by curator Gian Carlo Calza, who organized an exhibit called “Japan: Power and Splendor 1568-1868 “ in Milan, by the sections in exhibition: “Art and Nature,” “Power and Splendor,” “Forms of Design,” “The City,” “Tradition” and “Encounters with the West.” [Source: Roderick Conway Morris, New York Times, January 8, 2010]

Roderick Conway Morris wrote in the New York Times: Some scenes of the natural world...during the first half of the 17th-century when the Tokugawa shoguns were still watchful of any sign of dissent, are positively menacing with images of eagles from which other terrified animals take flight, and pine woods that have a minatory, muscular, contorted quality. Infinitely more peaceable and domestic in tone are subsequent delightful depictions of a family of gibbons, forming a simian chain from a branch to try to fish out a reflection of the moon shining on the surface of the water, by Kokan Myoyo, (1653-1717), and of apes exploring a mist-enshrouded outcrop of rocks, by Mori Sosen (1747-1821).

“The simultaneous development of ancient imported styles and ones that grew out of an indigenous tradition is also evident in the “Forms of Design” section, devoted to lacquer, woodwork, ceramics and the tea ceremony. For instance, the utensils employed in what was to become a quintessentially Japanese custom were initially imported from China and Korea. When the first local porcelain factory was opened in 1616, it was initially manned by Korean craftsmen. But in due course, ceramics echoing more native tastes — for example studiedly irregular raku vessels — also became an integral part of the complex tea-drinking ritual.”

Urbanization of Edo Period Art

Roderick Conway Morris wrote in the New York Times, “By 1700, the population of Edo, then one of the largest cities in the world, had reached around one million. A major factor in this explosion was the shoguns’ policy of obliging the 260 or so daimyo, or feudal lords, to spend alternate years in the administrative capital and their own provincial fiefdoms — leaving their families behind as pampered and honored hostages. The industries that proliferated to serve this expanding population of residents and dependants promoted the rise of a bourgeois class of merchants, artisans and entertainers. Meanwhile, even the samurai classes, their military duties radically reduced by decades of peace, took up other professions and artistic and artisanal tasks to make a living.” [Source: Roderick Conway Morris, New York Times, January 8, 2010]

“The center of Edo’s cultural ferment was the Yoshiwara pleasure district, with its tea houses, taverns, theaters, brothels and courtesans — who became the arbiters of fashion, parading the central thoroughfare with their entourages as though on a catwalk. The most high-ranking of these courtesans presided over salons attended by philosophers, poets, writers, artists, musicians and incognito aristocrats.”

“In another example of the transformation of an imported concept into something profoundly Japanese, a habitué of Yoshiwara, Asai Ryoi, in his “Ukiyo Monogatari” (Tales of the Floating World) of 1660, metamorphosed ukiyo, the mystical Buddhist idea of impermanence, into the bohemian concept of forgetting reality, of existing for the moment, living the life of the pleasure district to the full, singing songs, drinking sake and “like an empty gourd on the surface of the water going with the flow.”

Thus already in the 17th century, Yoshiwara with its bourgeois and aristocratic clients, its music, theater, bohemian artists and intellectuals, abundance of prostitutes and high-class “grandes horizontales,” in many ways prefigured the nightlife of Paris, London and other European capitals in the 19th century. Edo’s pleasure district and its activities produced a new art form, “ukiyo-e” (pictures of the floating world), the mass-market version being colored wood-block prints, for which many of Japan’s finest artists supplied designs, extending the range of the subject matter over time. When these prints arrived in Europe in the late 19th century, they would have a marked influence on the direction of Western art.”

“The City” section of the exhibition offers a superlative selection of screens, paintings and prints depicting the diverting, gorgeously colorful life of the pleasure district, including an amusing early 19th-century scroll painting narrating the journey by boat and on foot from Edo to Yoshiwara of three gods of good fortune, by Chobunsai Eishi, and captivating paintings of young beauties, one caught in autumn winds (by Isoda Koryusai) and another a snow storm (by Toensai Kanshi). Leading artists also contributed images for thousands of erotic prints (Shunga), represented here by an exceptionally refined sequence by Hokusai.”

Urban Art in the Edo Period

The rise of large urban areas, the increasing power and influence of the merchant class and a good network of roads and water routes in the Edo Period helped to take art out of the daimyo courts and bring it to the cities and ordinary hardworking and hard-partying Japanese. Artist liked the changes. They were able to sell their works to a much wider audience.

Urban Edo art, often in the form of colored prints, was more direct and rawer than daimyo art and often satirical and humorous. Robert Singer, the force behind a superb Edo Period exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in 1999, wrote that this kind of Edo art is characterized by "bold, sometimes brash expression...and playful outlook on life in general." [Source: Time magazine]

The subjects of urban Edo art were prostitutes, sumo wrestlers, popular actors, everyday life scenes, and people at work. Religious imagery sometimes was treated with irreverence and symbols were used that ordinary people could understand. There is clear link between Edo urban art and manga.

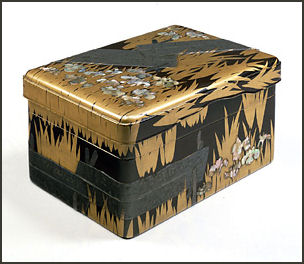

Edo Period Decorative Arts

Some of the greatest Edo art was works were neither paintings or sculpture but rather were things like writing boxes, tea bowls, and game boards. "It may be that no civilization, East of West, attained a greater refinement in the decorative arts than Edo Japan," wrote TIME art critic Robert Hughes. "Ceramics, lacquer and textiles were brought to an extraordinary pitch of aesthetic concentration by a large body of artisans."

"Skill was the key," Hughes wrote. "Edo artists and patrons loved virtuosity within a given medium, but they didn't have a hierarchy of art and craft. To them, the work or a lacquerer or papermaker was no less worthy than that of the screen painter, and in any case so many media could converge in a single work that art hierarchy became meaningless."

Edo art objects included polychromatic wood No masks of women who have become demons because they have been betrayed by love; “cheukei” fans used by No actors playing women roles; ceremonial samurai swords made of rayskin, lacquer, copper, gold, enamel, leather and steel; reptile-like samurai armor made from iron, leather, lacquer, silk and gold; leather saddles and stirrups embellished with gold and lacquer; and “uchiakake” ("outer garments" worn by samurai-class women), embroidered with blossoms, clouds and birds.

Ideas about the decorative arts made their way into cooking and perfumery. One Edo period cookbook illustrates 55 different ways to cut and display carp.

Samurai armor is another example of Edo decorative arts. Elaborate helmets, known as “kawari kabuto” (samurai parade masks), were created for ceremonial parades to Edo not battles. They featured a mind-boggling variety of decorative motifs, inspired by things like family crests, abalone shells, fans, carp's tails, clamshells, whirlpools, bat's ears, mountains, rivers, valleys and morning glory flowers. A number were made with large rabbit ears. Rabbits were admired by samurai because their speed. Others have what look like Mickey Mouse ears. Sometimes these were worn in battles to help samurai identify who was one their side and who wasn’t.

Edo Period Painting and Samurai

Many Edo period painters were samurai. Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Slicing through a torso with a curving steel blade and putting ink to silk with a liquid-loaded brush, both of these were stroke arts. Both required the same swiftness, the same lack of indecision. For the master of the brush and the master of the blade...the flawless stroke expressed a Japanese ideal — the beauty-governed union of sure, unhurried speed and centuries-old tradition, utter self-assurance and Zen purity of mind.”

Painting from Edo period was rich in drama and symbols. A painting of a carp swimming up a waterfall’something bottom-dwelling carp are unlikely to do — is seen as a manifestation of a fish becoming a dragon and viewed as an allegory of social climbing. An image of a monkey trying to catch a wasp is a warning to not cross a feudal lord as the Japanese words for word for “wasp” (“hachi”) and “fiefdom” (“hoch”) rhyme as do the ideograms “monkey” and “lord.”

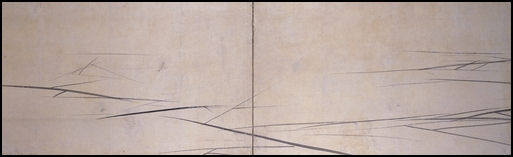

Cranes by Kano Eisen

Edo Period Decorative Painting

The Edo Period is sometimes refereed to as the Period of Cultural Maturity. Influential groups of decorative artists include the Sotatsu-Korin School, which revived decorative painting; the “Bunjin-ga”, which was influenced by Chinese Ming and Ching dynasty art; and the artists Maruyama Okyo and his student Nagasawa Rosetsu; and Matsuma Goshun, who stressed realistic portraits of nature.

The Rinpa School studied Chinese, Kano and Toso styles and developed its own highly original style of decorative painting with a lot of gold and vivid colors on screens and hanging scrolls. Famous 17th century Rinpa artists included Tawaraya Sotastsu (birth and death unknown), Hon'ami Koetsu (1558-1637), and Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858). The Toso school followed the Yamato-e style and concentrated in painting scenes from classical literature for wealthy clients.

“Tagasode” ("whose sleeves”") or sometimes “kasode” (small sleeves) was a style of suggestive and erotic Edo period screen painting that depicted women robes hung over their edge of the screen.

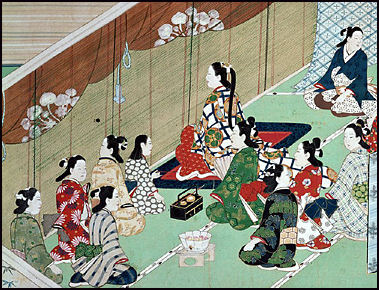

Edo Period Genre Painting

Genre painting, a style of art that depicting ordinary people going about the daily life, was very popular in the Edo Period. Painted on folding screens and scrolls, these works of art were filled with dozens of people, dancing, eating, and playing around, and are somewhat similar to works by the European artist Peter Brugel.

The “Hikone Screen” (1620s-40s) is a superb example of a “yurakuza” ("pleasure depiction"). A six panel screen painted on gold leaf, it is a bordello scene with dozens of figures doing things like playing board games, writing love letters and playing musical instruments.

painting by Kano Eitokeo

Kano School of Painting

The Kano School was famous for its gilded partition paintings of rich landscapes, flowers, birds and trees. It emerged in the Momoyama Period (1573-1603) and remained popular through the Edo Period. Originally based in Kyoto, it became official school of the shogunate and thus it method were kept secret. When some of its copybooks were leaked and published, the school scrambled to change its curriculum. It was founded and named after the artist Kano Masanobu (1434-1530).

The Kano school was led by members of the Kano family who inherited their positions. Artists were required to lean techniques by reproducing paintings drawn by it masters. The school originally stressed realism and strongly influenced by Chinese art bit over time become locked into a kind of formalism that stifled creativity and innovation. As part of their long training Kano school artist copied paintings regarded as masterpieces over and over again.

The longevity of the Kano school has as much to do with politics and art. It endured well into the 19th century because it shifted from Kyoto to Tokyo when the Tokugawa shogunate established their capital there and remained loyal to them while recruiting new recruits from different clans.

Kano Tanyu (1602-74) is regarded as the greatest Kano school artist. He is celebrated as a great master who took the Kano school to new places. Working in the early 17th century at a time when the shogunate was moving from Kyoto to Edo (Tokyo), he made wall paintings for Nagoya Castle and Nijo Castle in Kyoto and a series of scrolls depicting Tokugawa Ieyasu. He also convinced the school to move to Tokyo, a shrewd political move.

Among the other noteworthy Kano painters are Hanabusa Itcho (1652-17234), known for his ukiyo-e-influenced works and risque subjects; Kano Michinobu, who created light-hearted jovial works; and Kano Osanobu (1796-1846), who painted traditional subjects from interesting angles.

Early genre paintings usually depicted lots of people partying, working or carrying on outside. As the art form developed the number of figures was reduced, their activities were toned down, and the figures were brought inside. Late genre painting focused on single subjects, often a beautiful woman standing alone in a bathhouse or room.

Bamboo and Plums by Ogata Korin

Edo Period Artists

Humorous and innovative Edo artists also included Sengai Gibon, the creator of an amusing and beautiful rendering of a smiling frog in meditation; and Kuniyoshi who produced images of tattooed warriors fighting giant spiders and humongous snakes.

Ito Jakuchi (1716-1800) is known for his irreverent religious imagery, his use of vegetables as Buddhist symbols, and his experimentation with mosaic-like pointillism and other styles. He painted images of cranes,, eagles, plum blossoms, elephants, tigers and reeds waving in the snow. In “Grapevies” he paints leaves without outlines, using only wet washes in the so-called “boneless manner.” The tightly twisting tendrils and interwoven vines have not been allowed to cross.

Kawanabe Kyosai was another painter known for his humorous works. Describing a painting by Kyosai of the monk Daruma, Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Glowering on the wall is the ferocious monk...the legendary founder of the discipline of Zen. His eyes bulge. His brow is furrowed, his chest hairy. He is furious. Similarly intense are the coarse, impatient brush stroke of the gold-embroidered robes. Daruma dares the viewer to conquer self deception . But it is hard to take him seriously. Painting of this sort were once religious objects. This one is a party piece.”

Other well-regarded artists include Katayama Yokoku, who produced Chinese-style hanging scrolls: Watanabe Shiko (1883-1755), famous for his images of cranes; Nagasawa Rosetu, famed for his ghostly images of women; Mori Sosen (1747-1821), who painted such wonderful images of monkey people and said he would be reincarnted as a monk; and Sakai Hoitsu (1761-1828), the creator of elegant and refined screens and scrolls chronicling the changing seasons such as “Flowers and Grasses of Summer and Autumn”.

The brothers Ogata Korin and Ogata Kenzan produced lovely works. Ogata Korin (1658-1716) was a master of design and producer of lyrical paintings like “The Eight-Fold Bridge”). Ogata Kenzan (1663-1743) was a skilled potter who made ceramics with picturelike inscriptions. Hoitsu, Ogata Korin and Kiitsu all did their own versions “Wind and Thunder Gods”.

Maruyama Okyo cracked ice cool view for summer

Okyo and Rosetsu

The artist Maruyama Okyo (1733-1795) and his student Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754-1799) were known for their bold, innovative style.

Okyo was known for his sliding door paintings and is regarded as the father of modern Japanese painting and one of the first Japanese artist to develop truly unique Japanese style. He did this in part by blending sophisticated technique, elegance and realism, and merging Chinese traditions with Western methods such as perspective, and drawing directly from nature and models rather than from impressions of it. In 2007, Okyo’s “Cranes” was sold for $1,050,000 — triple the asking price — at a Christie’s auction. The 18th century pair of screens was the first Japanese work to sell for more an $1 million in over a decade.

Among Okyo masterpieces are “Unyru-zu” (“Dragon and Clouds”) and “Botan Kujaku-zu” (“Peonies and Peacocks”). The most famous works by Rosetsu are “Tora-zu” (“Tiger”) and “Yamauba-za” (“Mountain Woman”). Both artists produced large painting that over powered the viewer. The relationship between Okyo and Rosetu was stormy. Okyo kicked Rosetu out of his school three times but admired his technique enough to give him some important commissions. Rosetu died under mysterious circumstances when he was 46. It has been suggested that one of his rivals poisoned him out of jealousy.

Hon'ami Koetsu

Hon'ami Koetsu (1558-1637) is sometimes called the Leonardo da Vinci of Japanese art because of his extraordinary talent in a number of different art forms: painting, calligraphy, ceramics, poetry, the tea ceremony and lacquerware. He was equally adept at producing minimalist tea ceremony bowls, expressive paintings and wonderfully designed lacquer boxes.

Born into a family of swordsmiths, Koetsu prospered under the rule of the shogun Tokuagawa Ieyasu, who gave the artist a small village near Kyoto to work in. He worked with many other artists of his time and was described by some as good an "art director" as an "artist." Through his artistic career he also engaged in his trade, sword polishing.

Ukiyo-e Woodblock Printing

Ukiyo-e Woodblock Printing, See Separate Article

Image Sources: National Museum of Tokyo, British Museum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2011