JAPANESE PAINTING

Thunder God by Ogata Korin "Japanese painting, whether sacred or secular in theme," wrote Smithsonian Japanese art curator James Ulak, "have long been acknowledged for their ability to subtley evoke nature's beauty or to provide moving interpretations of religious experience."

The traditional formats of Japanese paintings’scrolls, albums, fans, folding screens and movable panels — were designed to encourage an intimate and adaptable relationship between the viewer and the work of art. Specific paintings were often meant to be contemplated during a particular season or occasion. Many Japanese paintings are made with a traditional Japanese bird's-eye perspective that differs from Western-style linear perspective.

Japanese paintings are often meant to be enjoyed in the settings they were created for. In this respect they much better enjoyed in the religious buildings and dwellings they were placed than in museums.

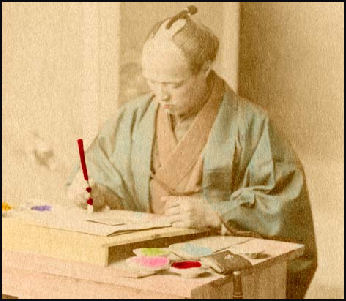

Art in the East developed very differently from art in the West. In Asia, calligraphy (the art of making letters) and painting evolved together and thus painting, the graphic arts, poetry and literature became linked together in way they never did in Europe.

“The parallel cultivation of both originality and ancient tradition are a recurring themes in Japan art,” Roderick Conway Morris wrote in the New York Times. “For example, while one screen depicts — against glittering backdrops of gold leaf — unmistakably Japanese scenes of ravens perched on snow-covered plum-tree branches on which the first small spring blossoms are flowering, another pair of screens in monochrome ink on paper shows sea- and mountain-scapes in the older Chinese style.

The expressive and philosophic aspirations of Chinese and Japanese painters were much higher than their counterparts in the West. Historian Daniel Boorstin wrote in “The Creators”, "their works were less varied in subject matter, color and materials. Their hopes and their triumphs offered nothing like the Western temptations to novelty, and their legacy is not easy for Western minds to understand." [Source: “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin]

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Web Japan web-japan.org/museum/paint.html ; Traditional Japanese Painting jref.com/gallery ; Museum of Fine Arts Boston mfa.org/collections ; What Is Emaki “ emaki.net/emaki ; Kano School of Painting metmuseum.org ;Screen and Partition Painting web-japan.org/museum ; Book: “Japanese Painting” by Terukazu Akiyama (Rizzoli, 1977). Calligraphy Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Nadja Van Ghelue Calligraphy Site theartofcalligraphy.com ; Japanese Calligrapy Gifts and Materials kanjistyle.com ; Shodo Designs shododesigns.com ; Japanese Calligraphy connectedglobe.com

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Art: Artelino on Japanese Art artelino.com ; Web Japan web-japan.org/museum/paint.html ; Japanese Art Portal japaneseart.org ; ; Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Zeroland zeroland.co.nz ; Asia Society Virtual Tour asiasociety.org ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com

Art History Sites Art History Resources on the Web — Japan witcombe.sbc.edu ; Early Japanese Visual Arts wsu.edu:8080 ; Japanese Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Books: “History of Japanese Art” by Penelope Mason (Harry N. Abrams, 1993); “The People' Culture — from Kyoto to Edo” by Yoshida Mitsukuni (Cosmo Public Relations Corporation, Tokyo, 1986); “The Shaping of Daimyou Culture, 1185-1868" by Martin Collcut and Yoshiaki Shimizu (National Gallery of Art, 1988).

Art Museums in Japan Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Tokyo National Museum site tnm.go.jp ; Kyoto National Museum official site kyohaku.go.jp ; Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Nara National Museum narahaku.go.jp ; Kyoto University Museum inet.museum.kyoto-u.ac.jp ; National Museum of Art, Osaka nmao.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Tokyo tobunken.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Nara nabunken.go.jp/english ;Miho Museum near Kyoto miho.or.jp ; Photos danheller.com

Museums with Good Collections of Japanese Art Outside of Japan ; Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston mfa.org/collections ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art lacma.org/art ; Ruth and Sherman Lee Institute for Japanese Art Collection ucmercedlibrary.info

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAINTING Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EDO PERIOD ART Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; UKIYO-E, HOKUSAI, HIROSHIGE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE POTTERY AND LACQUERWARE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Japanese Painters

"Japanese paintings were first produced under the patronage of Buddhist religious sects and aristocrats of the court,” wrote Smithsonian art curator Ann Yonemura. “Later, military leaders and merchants became avid patrons. Artists were almost always professionals, although Buddhism encouraged the practice of painting as a vehicle for meditation...Some educated Japanese emulated Chinese literati and took up painting as one of several genteel accomplishments suited to a cultured life."

"Japanese paintings," Yonemura wrote, "traditionally were produced by professionally-trained painters in hierarchically organized workshops that passed on skills and stylistic or iconographic models from generation to generation. Specialization of subjects and techniques was fostered by this system."

"Official Bureau of Panting produced work intended for use in imperial residences and for court ceremonies. Other workshops specialized in Buddhist devotion paintings and copies of scared texts" and "depictions of Chinese and Japanese narrative, landscape and natural subjects."

Japanese Painting Materials

Japanese painters and calligraphers essentially used the same materials and tools as their counterparts in China and Korea.

The tools and brush techniques for painting and calligraphy are virtually the same and calligraphy and painting are often considered sister arts. The traditional tools of the calligrapher and the painter are a brush, ink and an inkstone (used to mix the ink). Japanese calligraphers and painters both used brushes whose unique versatility was the result of a tapered tip, composed of careful groupings of animal hairs.

Brushes are called “fude” and ink is known as known as “sumi”. “Sumi” — jet black ink sticks — are preferred by Japanese calligraphers. The sticks were originally made from burning pine using a technique that is over 2,000 year old. Today they are made by scrapping soot from rapeseed oil lamps, mixing it with perfume and cowhide glue and then rolling it into a cylinder and pressing it into decorated molds. The sticks are dried slowly in damp ash and hung as long as three months. Sumi is made from in the winter. In the summer, the glue spoils in the heat and humidity.

Japanese artist excelled in the use of gold and silver leaf both as a pigment and applied as metal leaf.

Early Buddhist-Influenced Japanese Painting

13th century Buddhist painting Buddhism was the earliest and most important catalyst in the development of Japanese painting. Japanese artist borrowed Buddhist iconography that developed on the Asian continent and the content of the paintings was often determined the Buddhist schools to which the artists belonged.

Ulak wrote, "In every instance the artist attempted to create, through a single painting or an ensemble of paintings, an environment or moment of visual impact that complemented the faith of the viewer, enhanced a belief, and infused everyday life with a sense of transcendence."

The earliest works of Japanese painting that scholars are familiar with are Indian-, Chinese and Korean-influenced walls murals on Buddhist temples and tomb walls from the Asuka Period (A.D. 592-700); Very few art works from these periods exist today.

Some of the oldest existing works date back to the 12th century, when Pure Land Buddhism was in vogue. Artists from this sect produced gentle and compassionate deities. A genre of painting call raigozu featured the Amida Buddha and celestial attendants who accompanied the dead to the next world.

Early Chinese-Influenced Japanese Painting

Early Japanese landscape and nature paintings were influenced by the monochromatic painting of the Chinese Sung and Yuan periods. People who are not experts of Asian art have difficulty distinguishing Japanese art from Chinese art from this period. Common subjects include landscapes, flowers, birds, mountains, trees, armor-clad warriors, mountain hermits and major figures from Buddhism.

Natural subjects were important in Japanese art because man and nature are viewed as inseparable. Works of Japanese landscape art are regarded as organic wholes with background mountains, borders and backing colors considered just important as the flowers, trees, birds, animals or human figures in the middle of the picture.

The earliest examples of these painting were folding screen paintings from the Nara Period (A.D. 710-794); and landscapes painted on the screens and partitions of wooden structures during the Heian Period (794-1185).

The Heian Period (794-1185) saw the emergence of a unique Japanese style of painting called yamato-e that features indigenous subjects and was frequently used on screens and scroll paintings.

Scrolls in Japan

Many Japanese masterpieces are painted on scrolls, which are not intended to be hung or mounted on walls, but rather are meant to be stored in boxes and periodically taken out be looked at. This helps preserve the frail paint which breaks down when exposed to humidity and air. Collectors have traditionally unrolled their scrolls after the rainy season in the summer, savored them with some tea and returned them their boxes.

Scrolls unfortunately are one of the world's most fragile art forms. Careless handling, exposure to bright light and humidity, inept restoration, insects, temperature changes all contribute to the deterioration of paint. Plus, silk is a protein-based animal fiber that breaks down over time and has damaging chemical reactions with pigments and glues. Western oil paintings, by contrast, last longer because the pigments are preserved in oil and protected from by the elements by varnish.

Emaki Hand Scrolls in Japan

“Emaki” (painted hands scroll) emerged as a popular art form in the Heian Period (794-1185). Rolled and unrolled from one end to the other, these scrolls depicted movement and actions through a succession of scenes like a film strip. Indigenous to Japan, this style of painting broke from away from the tradition of Chinese-style landscape painting and developed in response to a demand for pictorial representations of literary works.

During the Kamakura Period (1192-1333) narrative hand scrolls found an audience among a wider range of people, partly because they could be enjoyed by illiterates. The number and kinds picture scrolls increased during this period. Regional war were common subjects and an effort was made individualize the figures.

The emaki format was used for romance stories, myths, biographies and animals stories about rabbits and frogs. Common individual scenes included depictions of love affairs, wars, miracles, comic and tragic events, mystical happenings, interacting animals and images of ordinary people as well as aristocrats. In many ways, they were not all that different from manga comic books. One 15th century emaki, “Kachie Emaki”, shows a contest to see who can produce the most powerful fart.

Viewers of emaki move their eyes from right to let on long horizontal sheets, creating an illusion of the picture moving. There is one story about a rich man who falls in love with a beautiful woman at first sight only to have her vanish before their wedding. In another story the owner of a storehouse finds himself flying in the air because of some mysterious power.

Famous Emaki

“Choju Jinbutsu Giga “ (“Scrolls of Frolicking Animals and Humans”) is a four volume set of ink-paint picture scrolls created by an unknown artist in the late Heian period (792-1192) to early Kamakura period (1192-1333). One of Japan's most beloved art works and regarded by some as the oldest example of manga, it shows hand-drawn animal figures, including a rabbit wrestling with a frog while two other rabbits look on, laughing and cheering. In a sumo-like pose the frog tries to trip up the rabbit while biting his long ears. The characters look like something out of a comic strip or a book of fables.

The “Choju Jinbutsi Giga” scrolls are kept out of view at Kyoto’s Kosanji Temple. It is not known why or even exactly when they were drawn. The entire work is made of four 10-meter-long scrolls. The first volume, ko, is the most beloved. It is filled with expressive depictions of animals such as rabbits, frogs, foxes and monkeys. One image shows some monkeys and rabbits swimming in a river, with one rabbit diving back into the river and another riding a deer while a monkey torments the rabbit, pouring water from the river on it. Another scene features an archery contest between two five-member teams of frogs and rabbits shooting at a large leaf.

The anonymous artist or artists who drew “Choju Jinbutsi Giga” were very skilled. The sumi ink lines are simple but delicately and powerfully rendered, giving the animals vivid expressions and muscle movements. Some think the figures were drawn by esoteric Buddhist monks. Others think they were made by court painters.

Recent research at the Kyoto National Museum has shown that at least some of the works were made on both sides of single sheets of washi paper — like a manga or comic book — and later pasted onto scrolls. A famous scroll of frogs and rabbits is 32 centimeters high and consists of 20 sheets of washi paper, each about 57 centimeters wide. The images were determined to have originally been on two-side sheets based on identical ink stains found on two different page of images.

“Genji Monogatari Emaki” (“Illustrated Tales of Genji”) is believed to be the oldest existing picture scroll. It depicts scenes from “The Tales of Genji” and is like a series of paintings that tell a story. The work is regarded as a treasure trove of details about the way people lived in the Heian period. “Shigisan Engi”, another famous emaki, depicts the priest Myoren using mystical powers to revive a famous temple.

Portrait Painting in Japan

Portrait painting became popular during the Kamakura Period (1192-1333) as part of a movement that emphasized individuality and realistic detail. A 13th century portrait of the first shogun Minamoto Yoritomo in the National Museum in Tokyo is almost as famous in Japan as the Mona Lisa is in the West.

Western painting techniques were introduced in the 16th century by Jesuits. Japanese portrait painters combined European oil paints with Japanese styles. Portraits of Western subjects often features Asian-style eyes.

Okyo tiger screen

Partition Painting and Folding Screens in Japan

Partition painting and folding screen painting were developed during Ashikaga Period (1338-1573) as a way for feudal lords to decorate their castles. This style of art featured bold India-ink lines and rich colors.

The Ashikaga Period also saw the development and popularization of hanging pictures (“kakemono”) and sliding panels (“fusuma”). These often featured images on a gilt background.

The Momoyama Period (1573-1603) was a time when the wealthy daimyo showed off their wealth by commissioning artist to produce paintings with flamboyant colors on brilliant gold leaf backgrounds. The subjects included landscapes, flowers, birds, trees and characters from Chinese folklore.

Gold and Silver in Japanese Painting

Hiroko Ihara wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Since ancient times, spotless, untarnished gold and silver have been coveted as symbols of wealth and power. But rather than follow in the footsteps of the splendiferous Incan Empire or gold-dominated Italian art, the Japanese tended to value its beauty in the dim reflections of gold and silver leaf applied to pieces of art and daily items.” [Source: Hiroko Ihara, Daily Yomiuri, January 21, 2011]

“Various motifs associated with nature, history and classical literature have been depicted on gold and silver backgrounds. Sometimes elegant, sometimes animated and dynamic, these motifs are enhanced by the unpretentiousness of the backgrounds. The pieces were created mainly during the Edo period (1603-1867) by artists belonging to the Rimpa school.

“Notable among the gold pieces is “Flowering Plants “ , a set of four fusuma sliding doors on which about 10 different flowering plants are drawn on the gold background. Ihara wrote: “Around the center of the doors are poppies that appear as dignified as a European queen. The other plants have been painted on both sides of the poppies as if paying homage to their beauty. Although no land has been depicted, the sweeping gold background gives the work depth and richness.

“The intriguing contrast of gold and silver can be seen on two sets of folding screens, both titled Red and White Plum Blossoms, each bearing motifs of the flowers. One, attributed to Korin has a gold background. The other, attributed to Hoitsu, has a silver background. Although they both depict blooming plum trees in animated, attractively twisted shapes, the impressions they leave are quite different.

"The first one illustrates the artists' enthusiasm for gold, which was common in the previous Momoyama period when feudal lords demonstrated their power even in works of art," Shinsaku Munakata, curator of an exhibit on gold and silver Japanese art at the Idemitsu Museum in Tokyo told the Daily Yomiuri. "The second one focuses on silver, the color of moonlight in ancient China. In Japan, moonlight gives grass, bush clover and other autumn flowers a dim silvery appearance and has been a popular poetic theme since ancient times. Artists were greatly attracted to it. The elegant colors of moonlight and twilight strike a strong chord within us with their essence of solitude and freedom."

Zen Painting in Japan

Zen Buddhism, which spread in the thirteenth century, introduced architecture and artistic works significantly different from those of other sects. In the fourteenth century, scroll painting largely gave way to ink painting, which took root in the prominent Zen monasteries of Kamakura and Kyoto. Zen painters — and more importantly, their patrons’showed a preference for an austere monochrome style, as introduced from Sung (960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) China. By the end of the 1400s, Zen painters and their patrons in Kyoto had developed a preference for monochrome landscape painting, called “suibokuga”. Among those Zen painters was Sesshu, a priest who went to China and studied Chinese paintings. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Ink painting, known as “sumie” or “shiboku”, were introduced by Zen monks from China during the Muromachi period Sung dynasty (1338-1573). Rendered primarily with black India ink, which is also used in calligraphy, these monochrome paintings eschewed color and emphasized and abstract and suggestive representations of natural objects.

Zen monks took up painting as a spiritual avocation and many became quite skilled at. Two famous Japanese artists that started as monks are Josetsu (“Trying to Catch a Fish with a Gourd”) and Shubun. The most famous Zen painter was Sesshu, a master of using landscapes to capture the refined sensibility of the Japanese spirit. His most famous works include “Landscapes of the Four Seasons, Autumn and Winter Landscapes” and “Landscapes”.

Edo period Zen masters like Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768) and Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) produced whimsical works that were sometimes comprised of only a few strokes of black ink on white paper. Sengai's “Frog in Zen Mediation” depicts a smiling frog and an calligraphy inscription that reads: "If by sitting in Zen meditation a human becomes a Buddha..." “Hotei”, which is a similar vein, depicts a jolly, naked pot-belied monk waving a fan.

Eraku studied classical calligraphy as a youth but burned all of his work after being exposed to the "unskilled" calligraphy of Daigu Sochiku and then dedicated his life to making calligraphy that expressed the human character rather than technical skill.

Edo Period Painting and Samurai

Many Edo period painters were samurai. Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Slicing through a torso with a curving steel blade and putting ink to silk with a liquid-loaded brush, both of these were stroke arts. Both required the same swiftness, the same lack of indecision. For the master of the brush and the master of the blade...the flawless stroke expressed a Japanese ideal — the beauty-governed union of sure, unhurried speed and centuries-old tradition, utter self-assurance and Zen purity of mind.”

Painting from Edo period was rich in drama and symbols. A painting of a carp swimming up a waterfall’something bottom-dwelling carp are unlikely to do — is seen as a manifestation of a fish becoming a dragon and viewed as an allegory of social climbing. An image of a monkey trying to catch a wasp is a warning to not cross a feudal lord as the Japanese words for word for “wasp” (“hachi”) and “fiefdom” (“hoch”) rhyme as do the ideograms “monkey” and “lord.”

Cranes by Kano Eisen

Edo Period Decorative Painting

The Edo Period is sometimes refereed to as the Period of Cultural Maturity. Influential groups of decorative artists include the Sotatsu-Korin School, which revived decorative painting; the “Bunjin-ga”, which was influenced by Chinese Ming and Ching dynasty art; and the artists Maruyama Okyo and his student Nagasawa Rosetsu; and Matsuma Goshun, who stressed realistic portraits of nature.

The Rinpa School studied Chinese, Kano and Toso styles and developed its own highly original style of decorative painting with a lot of gold and vivid colors on screens and hanging scrolls. Famous 17th century Rinpa artists included Tawaraya Sotastsu (birth and death unknown), Hon'ami Koetsu (1558-1637), and Suzuki Kiitsu (1796-1858). The Toso school followed the Yamato-e style and concentrated in painting scenes from classical literature for wealthy clients.

“Tagasode” ("whose sleeves?") or sometimes “kasode” (small sleeves) was a style of suggestive and erotic Edo period screen painting that depicted women robes hung over their edge of the screen.

Kano School, Boy on Mount Ibuku

Edo Period Genre Painting

Genre painting, a style of art that depicting ordinary people going about the daily life, was very popular in the Edo Period. Painted on folding screens and scrolls, these works of art were filled with dozens of people, dancing, eating, and playing around, and are somewhat similar to works by the European artist Peter Brugel.

The “Hikone Screen” (1620s-40s) is a superb example of a “yurakuza” ("pleasure depiction"). A six panel screen painted on gold leaf, it is a bordello scene with dozens of figures doing things like playing board games, writing love letters and playing musical instruments.

Early genre paintings usually depicted lots of people partying, working or carrying on outside. As the art form developed the number of figures was reduced, their activities were toned down, and the figures were brought inside. Late genre painting focused on single subjects, often a beautiful woman standing alone in a bathhouse or room.

Image Sources: National Museum of Tokyo, British Museum, Onmark productions.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013