JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY

Jomon pottery Diverse factors contributed to the development of Japanese art. Both technologically and aesthetically, it has for many centuries been influenced by Chinese styles and cultural developments, some of which came via Korea. More recently, Western techniques and artistic values have also added their impact. However, what emerged from this history of assimilated ideas and know-how from other cultures is an indigenous expression of taste that is uniquely Japanese. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

People living in Japan were the first known people to use pottery. Pottery from Japan dated to 10,000 B.C. is the oldest known in the world. Pottery is made by cooking soft clay at high temperatures until it hardens into an entirely new substance — ceramics. The pottery of the Jomon people was decorated with markings made by pressing lengths of cord into the wet clay before firing. The people who made it did not use a potter’s wheel.

While Japan was still in the Stone Age, China was making great advances in the arts and sciences. It makes sense then that the Japanese, once exposed to these advances through contacts with China, would try to bring some of them to Japan. Many of the cultural and artist forms brought from China and Korea were rooted in Buddhism, which in turn was influenced by the cultures of India and Tibet. Other forms from Persia and even Europe arrived via China and the Silk Road.

Between the fifth and ninth centuries Japan was a active importer of culture, particularly from China and Korea. Among the major imports were written characters, Buddhism, Confucianism, and knowhow and plans to build cities.

The 19th century and the early 20th century — when much of the world first learned about the extent and depth of Japan’s culture — was s a time when Japan exported culture: van Gogh copied Japanese woodblock prints, Charlie Chaplin befriended kabuki actors and “Madame Butterfly” and “ The Mikado” were popular among Western audiences.

Good Websites and Sources: Dogu Exhibition at the British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Japanese Creation Myth Washington State University ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Asuka and Astronomy 2.gol.com ; Heian Art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York metmuseum.org ; Heian Art at the British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Heian Art at the Tokyo National Museum www.tnm.jp/en ; The Tale of Genji.org (Good Site) taleofgenji.org ; ;The Age of the Samurai taots.co.uk ; Bushido, the Way of the Warrior /mcel.pacificu.edu ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Culture in the Edo Period Edo-Tokyo Museum edo-tokyo-museum.or.jp ; Edo Virtual Tour us-japan.org/edomatsu ; ; Edo Castle us-japan.org/edomatsu Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ;

Ukiyo-e Viewing Japanese Prints viewingjapaneseprints ; Ukiyo-e Pictures of te Floating World ukiyo-e.se ; Jim Breen’s Ukiyo-e Gallery csse.monash.edu.au/~jwb/ukiyoe ; Art.com www.art.com ; Artelino Japanese Prints artelino.com ; Gallery Sakura gallery-sakura.com ; Asian Collector’s Internet Auction woodblockprint.com ; Ukiyo-e from the Sweetbriar Collection artgallery.sbc.edu/ukiyoe ;

Culture in the Asuka Period (A.D. 592-700)

Asuka period Buddha During the Asuka period official delegations, engineers, builders, Buddhist priests, sculptors, medical experts and other came to Japan from Korea. Goods from Central Asia made their way to Japan on the Silk Road.

Mahayana (Greater Vehicle) Buddhism was introduced in the Asuka period. Mahayana religious themes would endure for over 500 years. The introduction of Mahayana Buddhism marked the beginning of the development of Japanese fine arts. At this time artisans turned their attention from ceramics and metalworks to Buddhist images, namely sculptures.

The earliest works of sculpture were created by Korean artisans. Example of their work remain at Horyuji Temple in Nara and Koryuji Temple in Kyoto.

Among the important cultural legacies of the Asuka period is “Manyoshu”, a literary treasure containing more than 4,500 poems which provide insights on how people lived at that time.

The oldest minted coins found in Japan were unearthed at the ancient site of Fujiwarakyu, the ancient capital from 694 to 710, in Kashihara, Nara. The Nihon Shoki contains reference to the of coins in A.D. 683.

Culture in the Nara Period (A.D. 710-794)

Nara's Todaji Temple The Nara period was a golden age for Japanese sculpture. Masterpieces from this period include the Yakushi Triad, which can be viewed at Yakushi Temple in southern Nara and the Ganjin statue at Nara's Toshodaiji Temple. Outstanding religious cave murals were also produced in these period.

The Shosoin Treasury is made up of 600 Nara-era items contributed by Empress Komyo to honor husband Emperor Shomu at a memorial service 49 days after his death.The items include the “Odo no Gosu” , a brass bowl with a pagoda-shaped lid used as an incense burner; the “Midori Ruri no Junikyoku Chohai” , a 12-lobed oblong cup of green glass with floral designs on surface that look like tulips; “Summie no Dankyu bow” , a toy designed to shoot balls instead of arrows; a wu-type musical instrument piece made of 17 small bamboo pipes set on a wooden receptacle with a pipe-like mouth piece with images of celestial children, birds in heaven and butterflies; and the “Koge Bachiru no Shaku” a red-stained ivory foot rule decorated with designs or animals, birds and flowers.

The “Kujakumon Shishu no Ban” is a Buddhist ritual banner embroidered with a peacock design that was displayed on the temple grounds during religious rituals. The banner is 81 centimeters long and 30 centimeters wide. It is believed to be have been made by court ladies but because there were no peacocks in Japan at the time it was made the design is thought to have come from abroad . Some of the cloth and textile pieces are in amazing condition considering how old they are.

Among the objects from ancient Korea and Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907) China are a wooly Kasen rug, covered with floral designs; the “Mokuga Shitan no Kikyoku” , a red sandalwood go board; “Shichijo Shino Juhishoku no Kesa”, a quilted priest’s robe made of seven strips of molted colors that was worn by Emperor Shomu; “Saikaku no Nyoi” , a stick made of rhinoceros horn decorated with ivory, crystals, pearls and lapis lazuli; and the “Ruri no Tsubo” , a lazurite jar with a funnel-shaped mouth with beautiful cobalt blue glass originally used as a spittoon.

Some regard Nara as the eastern most terminal and last stop of the Silk Road. Treasures brought on the Silk Road include reindeer antlers, a Persian brocade, an amber and mother-of-pearl inlaid mirror, an inlaid red sandalwood go board of Emperor Shomu (701-756). The surface of the go board is made of ivory. On the sides are images of camels and designs associated with Central Asia. The go stones are pieces of ivory died red and navy blue.

Historical Records in the Nara Period

The earliest written records of Japan were the “Kojiki” (The Record of Ancient Matters), written in A.D. 712 with Chinese characters depicting the Japanese language, and the “Nihon Shoki” (Japanese Chronicles), a document compiles in 720 that chronicles Japan's history from the birth of the first emperor to A.D. 697.

Both documents presented myths as if they were history, inserted fictitious rulers, and claimed the Japanese had a divine purpose on earth. It is likely based on oral tradition preserved by court officials who were blind and responsible for ritual and music.

The “Kojiki” is the oldest existing chronicle and oldest book written in Japanese. The “Nihon Shoki” has traditionally been a source of nationalist propaganda and was required reading for all schoolchildren until after World War II. Some scholars believe it was penned nu Fujiwara no Fuhito (659-720), one of the patriarchs of the Fujiwara clan to gloss over the murderous acts committed in the clan’s rise to power.

Culture in the Heian Period (794-1185)

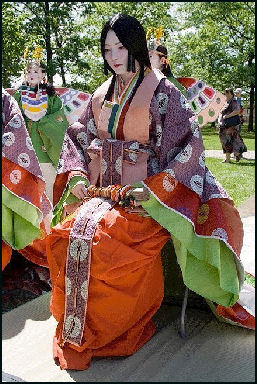

Heian period clothes The Heian period is regarded as one of the great periods of artistic and cultural development in Japan. Beginning at the end of the ninth century, as the Tang dynasty collapsed and contacts with China were interrupted, Japan began to distance itself from it large mainland neighbor and develop a culture that was more uniquely Japanese and simplified and refined versions of Chinese art forms.

The matriarchal family system the dominated Japanese social structures in ancient times was still in place in the Heian Period. There were female feudal lords, and economically-independent women artists and writers that left a distinct "feminine" imprint on the culture of that time.

Religion to some extent was separated from politics. The conflict between Buddhism and Shinto was dealt with making Shinto gods manifestations of Buddha. And, two important Buddhist sects — Tendai and Shingon — were founded by Japanese monks returning from China.

Heian period garments worn by nobles often had multiple layers and took many months to make. Courtiers wore “junihitoe”, which literally means 12 layers of silken robes but often included as many as 20, weighing several kilograms. The robes often changes according to the season and latest fashions.

In the Heian Period nobles dressed in “kariginu” robes made of silk and “ebosho” brimless headgear. Wearing the kariginu straightened the posture and forced one to walk slowly, When doing something one had to use one hand to pull back the dangling sleeves. In the spring nobles wore a white, diaphanous robe over a red inner robe, or visa versa. The two styles (white over red and red over white) appeared pink, but differed slightly expressing the different shades of the color in early and late spring.

Writing in the Heian Period

During the Heian period, Japanese script was developed. Chinese characters were often unsuited for certain Japanese sounds and priests developed two sets of writing based on Chinese forms. By the middle of the Heian period these forms were unified and simplified into a writing form called “kana”. As the use of kana become widespread, it paved the way for the development of a unique Japanese literary styles.

The first known example of mass printing was ordered by the Japan nun-empress Koken (718-770) to avoid a recurrence of a smallpox epidemic that occurred in 735-37. To expel the demons of disease she ordered 116 priests to have the people of Japan build one million four-and-half-inch-high, three-story pagodas with twenty lines of text written inside. The prayers were made with the world's oldest known examples of copper printing on paper.

Tale of Genji

“Tale of Genji” is Japan's most famous classical literary work. Regarded by some scholars as the world's first important novel and the first psychological novel, it was written as an epic poem by Murasaki Shikibu (975-1014), a lady from the Japan Imperial court, between A.D. 1008-20.

As a literary treasure “Tale of Genji” is to the Japanese what “The Odyssey” and “The Iliad” are to the West. It is written in episodes as if serialized in a magazine. It was written mostly in hiragana as women at the time were not supposed to learn kanji (Chinese characters).

The “Tale of Genji” story features an expressive narrative and a diverse cast of characters and is filled with details about court life in the mid Heian period and aesthetic pursuits that are still alive today: waka poetry, gakaku court music, noh and the tea ceremony.

The main character, Prince Hikaru Genji, is believed to be modeled after Minamoto no Toru, a minister in the early Heian period (794-1192). Some see the novel as a moralistic tale because Prince Genji had an affair with his father’s mistress and was punished by having his own wife seduced by another man. Genji means the "shining one.”

See “Tale of Genji”, Literature, Culture

Culture in the Kamakura Period (1185-1333)

13th century wood sculpture In the Kamakura period (1185 and 1333) Zen had a large impact on Japanese art and culture as manifested in the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, calligraphy, ink paintings, haiku poetry, gardening, sculpture and textiles.

The golden age of Japanese sculpture was in Kamakura Period (1192-1333), when wooden statues of a wide range of subjects, including serene hermits, fierce warriors and omnipotent gods, were carved with wonderful detail and realism from blocks of woods fit together. Some the wooden figures feature realistic even humorous poses.

Famous sculptors include Kokei (active in the lat 12th and early 13th century), and his son Unkei (died 1223). Unkei produced magnificent wooden sculptures with crystals inset in the eyes. He images of important figures in Japanese Buddhism and known for being expressive and austere.

Kokei worked during the Heian period (794-1192) and early Kamakura period (1192-1333). He made sculptures of Buddha from cypress wood. Experts determine works made him based on pleats in clothing and the shape of the ears.

Unkei lived in the early Kamakura period (1192-1333). The years of his birth is unknown. He develop the Kamakura-style of carving and led the Nara-based Kei school of Buddhist sculpture. He played a major role in rebuilding large temples ruined by battles that took place in the Heian period.

Some trace the tea ceremony back to Eisai (See Above), who introduced to Japan a new method for making powdered green tea. A member of the Rinzai school of Zen, he is said to have brought back tea seeds from tea bushes from China and planted them at his temple. At that time tea had a number of health benefits ascribed ti it in China and was used to harmonize different parts of the body.

Culture in the Ashikaga Period (1338-1573)

Under the Ashikaga shogunate, samurai warrior culture and Zen Buddhism reached its peak. Daimyos and samurai grew more powerful and promoted a martial ideology. Samurai became involved in the arts and, under the influence of Zen Buddhism, samurai artists created great works that emphasized restrain and simplicity. Landscape painting, classical noh drama, flower arranging, tea ceremony and gardening all blossomed.

Under the Ashikaga shogunate, samurai warrior culture and Zen Buddhism reached its peak. Daimyos and samurai grew more powerful and promoted a martial ideology. Samurai became involved in the arts and, under the influence of Zen Buddhism, samurai artists created great works that emphasized restrain and simplicity. Landscape painting, classical noh drama, flower arranging, tea ceremony and gardening all blossomed.

Partition painting and folding screen painting were developed during Ashikaga Period (1338-1573) as a way for feudal lords to decorate their castles. This style of art featured bold India-ink lines and rich colors.

The Ashikaga Period also saw the development and popularization of hanging pictures (“kakemono”) and sliding panels (“fusuma”). These often featured images on a gilt background.

The true tea ceremony was devised by Murata Juko (died 1490), an advisor to the Shogun Ashikaga. Juko believed one of the greatest pleasures in life was to live like a hermit in harmony with nature, and he created the tea ceremony to evoke this pleasure.

The art of flower arranging developed during the Ashikaga Period along with the tea ceremony although its origins can be traced to ritual flower offerings in Buddhist temples, which began in the 6th century. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa developed a sophisticated form of flower arrangement. His palaces and small tea houses contained a small alcove where a flower arrangement or work of art was placed. During this period a simple form of flower arrangement was devised for this alcove (the tokonoma) that all classes of people could enjoy.

Culture in the Momoyama Period (1573-1603)

Rikyu tea ceremony bowl The brief, brilliant Momoyama period served as link between medieval and early modern Japan. "It was an age of building, recovery, revival, extensive cultural patronage and competitive displays of ostentation." Momoyama period art included huge gardens, gilded screen paintings and brilliant textile work.

The Momoyama Period (1573-1603) was a time when the wealthy daimyo showed off their wealth by commissioning artist to produce paintings with flamboyant colors on brilliant gold leaf backgrounds. The subjects included landscapes, flowers, birds, trees and characters from Chinese folklore.

The art flourished under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The new elite commissioned artists to produce grand works of art to decorate their palaces. The Kano School, famous for its gilded partition paintings of rich landscapes, flowers, birds and trees, emerged in the Momoyama Period and remained popular through the Edo Period.

Japanese ceramics flourished during the Momoyama Period (1573-1603) and it development as an art form was boosted by the popularity of the tea ceremony. Famous Oribe and Shinto tea ceremony ceramics were produced under the direction of tea master Furuta Oribe and Sen no Rikyo. The master potter Chojiro developed the raku-yaki style of pottery after being ordered to do so by the shogun.

The form of tea ceremony practiced today was created in the late 1500s by the tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591). He served as tea master for Hideyoshi Toyotomi and is credited with simplifying the tea ceremony in accordance with Zen ethos and the concept of wabi (simplicity) and bringing the tea ceremony from the upper classes to ordinary people. He replaced Chinese porcelain with hand-molded Japanese ceramics formalized the austere aesthetic and emphasized the use simple tools that reflected the unpredictable aspects of nature. Rikyu died after committing ritual suicide for reasons that are still mysterious.

Momoyama period tea ceremony wasn’t all austerity. Rikyu’s protégé and successor, Furuta Oribe (1543-1615), preserved the wabi style but also experimented with it. Ceramics created under his tutelage were strangely formed and colored with greens and yellows. Pieces that were cracked and had odd asymmetrical shapes were greatly prized. Others were shaped like pinwheels and flowers. He too died by his own sword on the command of Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Culture in the Edo Period (1603-1868)

"During the Edo Period (1603-1868) both the subjects and styles of painting diversified significantly," wrote Smithsonian art curator Ann Yonemura, "as patronage broadened to include a newly affluent merchant class. Genre painting of contemporary urban life, new subjects and styles influenced by a limited importation of European art, and work by artists who based the lives on Chinese scholarly ideals flourished."

The Genroku era in the late 17th and early 18th century is sometimes regarded as the golden age of Japanese art, Kabuki plays, haiku poetry, and woodblock printing.

Edo period Japanese art is very popular worldwide. An Edo art touring exhibit drew 900,000 people in 2007, making it the most seen art show in the world that year.

Book: “Art of Edo Japan” by Christine Guth (Harry N. Abrams, 1996).

See Edo Art. Arts and Culture

Daimyo, Samurai and Art in the Edo Period

The Edo Period was a time of relative peace. With no wars to fight and non-Japanese restricted from entering the country, the shoguns and daimyos (landed aristocrats) and samurai under them, concentrated their energies on the administration of the estates and pursuit of the art forms such as poetry, painting, architecture, No theater, calligraphy, flower arranging and the tea ceremony. With no foreigners to distract them, the daimyos and samurai were able to develop and refine art forms that were uniquely Japanese.

The emphasis on the arts was intended in part to keep the minds of military men off of military matters. "In daimyo Japan," Bennet Shiff wrote in Smithsonian magazine, "culture became synonymous with authority. Lords competed with one another in high art, tea, theater, poetry and the employment of artists, actors, poets, tea masters. Frequently they practiced one or two arts themselves. Not to participate was to be dropped out of what was meaningful and necessary. It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to name another society in world history in which art was so much a part of daily existence."

Urban Art in the Edo Period

The rise of large urban areas, the increasing power and influence of the merchant class and a good network of roads and water routes in the Edo Period helped to take art out of the daimyo courts and bring it to the cities and ordinary hardworking and hard-partying Japanese. Artist liked the changes. They were able to sell their works to a much wider audience.

Urban Edo art, often in the form of colored prints, was more direct and rawer than daimyo art and often satirical and humorous. Robert Singer, the force behind a superb Edo Period exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in 1999, wrote that this kind of Edo art is characterized by "bold, sometimes brash expression...and playful outlook on life in general." [Source: Time magazine]

The subjects of urban Edo art were prostitutes, sumo wrestlers, popular actors, everyday life scenes, and people at work. Religious imagery sometimes was treated with irreverence and symbols were used that ordinary people could understand. There is clear link between Edo urban art and manga.

Edo Period Decorative Arts

Edo writing box Some of the greatest Edo art was works were neither paintings or sculpture but rather were things like writing boxes, tea bowls, and game boards. "It may be that no civilization, East of West, attained a greater refinement in the decorative arts than Edo Japan," wrote TIME art critic Robert Hughes. "Ceramics, lacquer and textiles were brought to an extraordinary pitch of aesthetic concentration by a large body of artisans."

"Skill was the key," Hughes wrote. "Edo artists and patrons loved virtuosity within a given medium, but they didn't have a hierarchy of art and craft. To them, the work or a lacquerer or papermaker was no less worthy than that of the screen painter, and in any case so many media could converge in a single work that art hierarchy became meaningless."

Edo art objects included polychromatic wood No masks of women who have become demons because they have been betrayed by love; “cheukei” fans used by No actors playing women roles; ceremonial samurai swords made of rayskin, lacquer, copper, gold, enamel, leather and steel; reptile-like samurai armor made from iron, leather, lacquer, silk and gold; leather saddles and stirrups embellished with gold and lacquer; and “uchiakake” ("outer garments" worn by samurai-class women), embroidered with blossoms, clouds and birds.

Ideas about the decorative arts made their way into cooking and perfumery. One Edo period cookbook illustrates 55 different ways to cut and display carp.

Edo Period Painting and Samurai

Many Edo period painters were samurai. Paul Richard wrote in the Washington Post: “Slicing through a torso with a curving steel blade and putting ink to silk with a liquid-loaded brush, both of these were stroke arts. Both required the same swiftness, the same lack of indecision. For the master of the brush and the master of the blade...the flawless stroke expressed a Japanese ideal — the beauty-governed union of sure, unhurried speed and centuries-old tradition, utter self-assurance and Zen purity of mind.”

Painting from Edo period was rich in drama and symbols. A painting of a carp swimming up a waterfall’something bottom-dwelling carp are unlikely to do — is seen as a manifestation of a fish becoming a dragon and viewed as an allegory of social climbing. An image of a monkey trying to catch a wasp is a warning to not cross a feudal lord as the Japanese words for word for “wasp” (“hachi”) and “fiefdom” (“hoch”) rhyme as do the ideograms “monkey” and “lord.”

Woodblock Printing in Japan

Woodblock printing in Japan is known as “ukiyo-e”, literally "pictures of the floating world." One of the most popular forms of Japanese art, it was created for the contemporary masses and depicts images of urban life and natural scenes that ordinary people could relate to and enjoy. The "floating world" is a Buddhist metaphor that refers to the changing world of fleeting pleasures, which were often found both in seasonal changes of nature and the entertainment districts of Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto.

“Ukiyo-e” is derived from “uki,” a Buddhist-derived term denoting the state of mind conveyed by the German word “weltschmerz” (“disenchantment with the actual,” or “world weariness”). During the Edo period the kanji (Chinese character) for “uki” was replaced, playfully, by the homophone kanji for “float” and “ukiyo” took on antithetical meaning — the worldly “sea of trouble” became “sea of tranquility,” in which impermanence was celebrated not lamented. [Source: Mark Austin, Daily Yomiuri]

Among the Westerners who collected ukiyo-e were Vincent Van Gogh, the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright and the painter Claud Monet, who was particularly found of Utamaro and Hokusai. Wright once said, "The Japanese print is one of the most amazing products of the world and I think no nation has anything to compare with it."

Van Gogh copied “Plum Garden in Kameido” and “Great Bridge , Sudden Shower at Atakae” from Hiroshige’s “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo”. The background of Van Gogh’s “Portrait of Pere Tanguay” shows several ukiyo-e’s that the artist collected.

Ukiyo-e prints are famous for their exquisite calligraphic lines, bold composition, dramatic colors and flat, unshaded subjects. Some images are serene and dignified and look at home in museum while others are full of drama and violence and look as if they belong in a comic book. Usually only a few hundred or a few thousand prints were made. On average a printer could make about 200 prints a day.

Ukiyo-e was inspired by everyday Edo pleasures and urban leisure pursuits like drinking, whoring and attending Kabuki theaters as well as scenic spots around Japan. Ukiyo-e prints depicted tea ceremonies, theaters, sumo wrestlers, women bathing in wooden tubs, picnics under cherry trees, excursions to pastoral lakes, prostitutes, sexual acts, actors, and make-believe characters like warriors, mythical animals and monsters. One major source of inspiration was Yoshiwara, an entertainment district in Edo (Tokyo), where daimyos and members of the Imperial court mingled, attended sumo bouts and kabuki plays and enjoyed the company of prostitutes.

Book: “Japanese Woodblock Printing” by Rebecca Salter (A&C Black, 2001).

History of Woodblock Printing in Japan

Woodblock printing originated in China but was greatly improved by the Japanese through the skill of Japanese craftsmen and introductions of washi paper; which tolerates repeated printing and absorbs color without collapsing; the development of the kento method or printing, which ensured that layers of were color correctly applied and aligned; and invention of the “baren”, a circular pad mad from compressed laminated paper that was used in manual printing to apply the flat colors so pleasing to fans if ukiyo-e.

The first ukiyo-e in the 17th century were simple monochrome black prints. Later "red prints" appeared. They were followed by yellow and green prints, and eventually full color prints known as “nishikie”, were developed in the middle of the 18th century.

Ukiyo-e was reportedly founded by a printer named Iwa Matabie and popularized, beginning in 1681, by Hishikawa Moronobu, an artist who lived among ordinary people and found inspiration among them. He rose to fame by producing images of famous erotic tales, scenes from the entertainment district in Yoshiwara and portraits of beautiful women. As an art form ukiyo-e drew on and synthesized Chinese painting. Yamato-e (classical Japanese Painting) and byobu-e (screen painting).

Techniques of Japanese woodblock printing originated in Kyoto and Osaka but are most closely associated with Edo (Tokyo). Early prints from the Edo Period between 1660 and 1720 featured only black and white printing. Color printing had not been invented and colors were applied by hand. Many early ukiyo-e were how-to sex manuals for brides and courtesans and erotic prints pertaining to the red-light entertainment districts in Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto,

Many of the of the best works of ukiyo-e are found now outside of Japan in places like British Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Many of these were snatched up in the years following the end of Edo Period — as Japan rushed towards modernization” when ukiyo-e was seen as passe and disposable, and Western collectors acquired huge masses of work for a song. Almost half of the 25,000 prints, books and paintings at the Victoria &Albert Museum — regarded as one of the largest and finest collections of ukiyo-e n the world — was obtained in a single purchase from a London dealer in 1886.

Kabuki and Geishas in the Edo Period

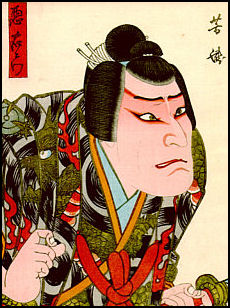

The first formally recognized kabuki show was performed in Kyoto at in 1603 — the same year the Edo Period began — by a Shinto priestess named Izumo no Okuni and her troupe of female dancers to raise money for Izumo Taisha shrine. Though based on Buddhist prayer dances, early shows were generally romantic tales intended as popular entertainment. Like Noh, kabuki has its roots in drama, music and dance that can be traced back to the eight century.

Kabuki was inspired by the activities of Kabuimono, urban youths who were the punks of their day. They traveled in armed groups, thumbing their nose at middle class values and harassed anyone who got in their way.

Early Kabuki, known as “kabuki odori” (which roughly means “avant guard dance") were primarily dances, often known for their lewdness and vulgarity. Although women helped popularize the art they were banned from Kabuki in 1629 because many of the lead actresses were prostitutes and producers were concerned about fights breaking out between men trying to win the attention of the actresses. See Arts and Culture, Theater, Kabuki

Geishas first appeared in brothels in the pleasure quarters of Tokyo and Osaka in the 17th century. Their job was to entertain bar and inn customers with dancing and music. A “geiko” (literally "arts child") is the Kyoto expression for a geisha.

The earliest geishas were men known as “taiko-mouchi” (literally "drum carrier"). Like their female counterparts today, they charmed male clients with conservation, service, performances and sexual innuendo. There were around a half dozen “taiko-mouchi” still alive in the 1990s.

It wasn't until the mid 18th century that the geisha profession was dominated by women. In the 19th century geishas were the equivalent of supermodels. The most well-known ones earned substantial incomes and influenced fashion and popular culture. In a world where women were either wives of prostitutes, geisha lived in separate communities known as the "flower and willow world." See Arts and Culture, Theater, Geishas

Manga in the Edo Period

Some trace the origin of manga back to nishiki-e prints made in the Edo period. These prints were often satirical and instilled with humor and fun, qualities found in modern manga “I think they share a similar espirit, satisfying the purpose of entertaining people.” The term "manga" was coined by the famous wood block print artist Katsushika Hokusai (1761-1849). Although he produced graphic images he did not produce true manga that tell narrative stories.

True manga has its roots in 19th century one-panel and later multi-panel newspapers and magazine cartoons that depicted political, satirical and humorous subjects. Some also trace its roots to the Japanese written language, which has so many symbols and characters it wasn’t easily adaptable to movable type, and often it was just as easy to make wood blocks with words and illustration as it was to make wood block with long texts. By contrast, the Roman alphabet with is 26 symbols was adaptable to movable type.

Japanese Culture in the 19th and 20th Century

Astroboy's birth The Meiji Period also resulted in the revival of traditional Imperial art forms such as waka and haiku poetry and nurtured an interest in Western painting and sculpture. Japanese culture also made its way west. Westerners were excited about buying silks and porcelains in the 1880s. Artist like Van Gogh and Gauguin were inspired by Japanese art,

Japonism craze was in Paris on the late 19th century. Europe as a whole and the French in particular were enthraled with all things Japanese, particularly wood block prints, geishas, and kabuki. Japonism became an art movement that was influenced by ukiyo-e and other forms of Japanese art. Among those that were greatly influenced by it were Van Gogh. Centered in France, the artists that participated in it recognized the value of Japanese art through its own sensibilities. It can be argued that they appreciated ukiyo-e and other arts more than the Japanese did.

U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant visited Japan in 1879. During the trip he was particularly impressed by a Noh performance he saw and said Japan must takes pains not to modernize too quickly and lose its traditions.

Image Sources: 1) 7), 8), 11) Tokyo National Museum 2) onmark productions 3) Ray Kinnane 4) Liza Dalby Tale of Genji website 5) Japan Zone 9) British Museum 10) 12), 13) artelino online art shop, 14) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education) 15), Japan Zone

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2012