JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE

traditional tea house Austere construction methods, lightweight materials and porous boundaries between inside and outside are all hallmarks of traditional Japanese architecture. Pritzker-prize-winning Japanese architect Ryue Nishikawa told AP, “If you see Japanese temples made of wood, you can see how the architecture is made up. They have a clear construction and transparency and they are quite simple.”

"While Western architects would battle the elements," historian Daniel Boorstin wrote in The Creators, "the Japanese, admiring their power, have sought ways to exploit their charms." Western architects over the centuries have traditionally chosen strong, resistant stone to overpower nature to produce monumental and towering structures while Japanese architects aimed to be more in harmony with nature and chose wood as their predominate building material. Even today most of Japan's oldest surviving buildings and most famous shrines and temples are made of wood.

Also, while Western architecture has often featured spires and other vertical features that intended to show the power of God and man over nature, Japan temples and shrines usually stressed the horizontal and were often relatively small and hidden by trees and other natural objects.

Japan is credited with inventing minimalist design. Unlike Western architects who have traditionally tried to make to make their buildings interesting to look at by adding unnecessary decorations and arranging modules of differing heights, Japanese architects focused on making their structures sublime and mysterious on a horizontal level. It has been said that with traditional Japanese architecture you start with one room and take a great effort to get that right before moving on to the next room.

Websites and Resources

traditional Japanese house

Good Websites and Sources: Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System (JAANUS) Terminology Search http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus ; Herbert Offen Collection Peabody Essex Museum ; Japanese Architecture in Kansai kippo.or.jp/culture ; Wikipedia article on Japanese Architecture wikipedia.org ; Japanese Architecture in Kyoto kyoto-inet.or.jp ; About Japan: Architecture csuohio.edu ; Asian Historical Architecture orientalarchitecture.com ; Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com ;

Houses in Japan: Japanese Houses on KidsWeb web-japan.org/kidsweb ; About Homes csuohio.edu/class ;Traditional Japanese Design eastwindinc.com ; Businessweek Piece on Micro Homes images.businessweek.com ; Japanese Design japanesehomeandbath.com ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Housing Section stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; Traditional Japan, Key Aspects of Japan japanlink.co ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles with a section on traditional houses (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese) shirofan.com ;

Thatch Roof Houses of the Shokawa Valley: Shirakawa Grasso Houses shirakawa-go.org/english ; Japan Guide japan-guide JNTO article JNTO Map: Japan National Tourism Organization JNTO UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO Utsukushi-ga-Hara Open Air Museum Website: JNTO article JNTO

Castles : Castles of Japan pages.ca.inter.net ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese shirofan.com ; Edo Castle us-japan.org/edomatsu Matsumoto Castle on Matsumoto City tourism welcome.city.matsumoto.nagano.jp ; Wikipedia Wikipedia Nagoya Castle Official site nagoyajo.city.nagoya ; Himeji Castle Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Himeji castle virtual tour himeji-castle.gr.jp ; Himeji Tourist Information himeji-kanko.jp Himeji Tourist Information Map himeji-kanko.jp UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website ; Osaka Castle Osaka Castle Site osakacastle.net ; Japanese Castle Explorer .japanese-castle-explorer.com ; Wikipedia Wikipedia Osaka Castle Map: Japan National Tourism Organization JNTO

Buddhist Temples: Good Photos of Temples at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Good Photos of Pagodas at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Temples and Shrines in Nara Park Kofukuji site kohfukuji.com ; Yamasa yamasa.org ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website; Kasuga Taisha Shrine (in Nara Park) Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Japan Guide japan-guide.com ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website Todaiji Temple in Wikipedia Wikipedia UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website Toshodaiji in Japan Guide japan-guide.com UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website

Shinto Shrines Good Photos of Shrines at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Good Photos of Shrine Gates at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Ise Shrine, Isejinguisejingu.or.jp ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Wikitravel Wikitravel ; Map in Japan National Tourism Organization JNTO and Ise area JNTO ; Ise Jingu isejingu.or.jp Izumo Taisha (20 miles west of Matsue) is the second most important Shinto shrine after the one in Ise. Websites: Wikipedia Wikipedia ; JNTO article JNTO ; Japan Guide japan-guide Shimogamo Shrine shimogamo-jinja.or.jp ; Welcome to Kyoto pref.kyoto.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website Kamigamo Shrine kamigamojinja.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine (Near Kyoto and Inari Station on the JR Nara line) is the main shrine of more than 30,000 Inari Shinto shrines scattered throughout Japan. Websites: Japan Reference jref.com ; Fast Rider farstrider.net ; Photos jref.com

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GARDENS AND BONSAI IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE ARCHITECTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HOMES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ROOMS AND APPLIANCES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO SHRINES, PRIESTS, RITUALS AND CUSTOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST GODS, TEMPLES AND MONKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Early History of Japanese Architecture

Historically, architecture in Japan was influenced by Chinese architecture, although the differences between the two are many. Whereas the exposed wood in Chinese buildings is painted, in Japanese buildings it traditionally has not been. Also, Chinese architecture was based on a lifestyle that included the use of chairs, while in Japan people customarily sat on the floor.

Methods for Buddhist architecture were introduced by two skilled workers from the Paekche kingdom in Korea in 577. The skills they introduced were used to construct Japan’s first Buddhist temple, Asukamura, in Asuka, Nara Prefecture. In the late 7th century four temples — Asukadera, Kawaradera,Yakushji and Daikandaiji, were built. They were financed by the government and built by skilled construction workers and sculptors formed into teams. Elite workers learned the latest architecture methods from delegates who traveled abroad on Kentoshi ships to Tang dynasty China.

In 710, when the capital of Japan was moved 18.4 kilometer from Fujiwara-kyo to present-day Nara city, a unprecedented construction boom ensued. Yakushji, Asukadera (now Gangoji) and Daikandaiji (now Daianji) were moved to new sites and Kofukiji was built by Fujiwara Fuhito, the nobleman who orchestrated the move to Nara.

Nara city itself was modeled after Changan, the capital of Tang Dynasty China. The city was divided into a western capital and eastern capital, which together measured 4.9 kilometers from north to south and 4.3 kilometers from east to west. Geyoko, an extension of the eastern side of the eastern capital, was 2.1 kilometers from north to south and 1.6 kilometers from east to west.

Development of Japanese Architecture

“Architecture in Japan has also been influenced by the climate. Summers in most of Japan are long, hot, and humid, a fact that is clearly reflected in the way homes are built. The traditional house is raised somewhat so that the air can move around and beneath it. Wood was the material of choice because it is cool in summer, warm in winter, and more flexible when subjected to earthquakes. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“In the Asuka period (593-710), Buddhism was introduced into Japan from China, and Buddhist temples were built in the continental manner. From this time on, Buddhist architecture had a profound influence on architecture in Japan. The Horyuji temple, originally built in 607 and rebuilt shortly after a 670 fire, includes the oldest wooden structures in the world. It is among the Buddhist monuments in the Horyuji area that were registered as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1993.

“In the Nara period (710-794), a capital city called Heijokyo was laid out in Nara in a manner similar to the Chinese capital, whereby streets were arranged in a checkerboard pattern. Many temples and palace buildings of this period were built in the Tang style of China. In the Heian period (794-1185), Chinese elements were fully assimilated and a truly national style developed. The homes of the nobility in Heiankyo, now Kyoto, were built in the “ shinden-zukuri “style, in which the main buildings and sleeping quarters stood in the center and were connected to other surrounding apartments by corridors. Many castles were built in the sixteenth century, when feudal lords dominated Japanese society. Though constructed for military defense, these castles were also used to enhance the local lord’s prestige and as his residence. A few of them remain today, admired especially for their “ tenshukaku “(donjon).

“The buildings used as living space inside the castle grounds, and also the living quarters at Buddhist temples, were frequently built in the domestic architecture style known as “ shoin-zukuri”, which incorporated new features — including translucent and opaque paper-covered sliding panels (“ shoji “and “ fusuma”, respectively) and rush mats (“ tatami”) — that are still key elements of the traditional Japanese house. The most magnificent extant example of this style is the seventeenth-century Ninomaru Palace of Nijo Castle in Kyoto.

“In the seventeenth century, the “ shoinzukuri “style was combined with features characteristic of “ sukiya”, the teahouse in which the tea ceremony is performed, to create the “ sukiya-zukuri “style of domestic architecture. Characterized by a delicate sensibility, slender wooden elements, and unornamented simplicity, this style’s finest extant example is the Katsura Detached Palace (Kyoto), which is famous for its harmonious blending of buildings with the landscape garden.

Features of Japanese Architecture

Post-and-lintel structures provide traditional Japanese buildings with strength over a wide area. Instead of the laying cornerstone to dedicate a new building, Japanese builders plant a decorative and symbolic ridgepole in an important ceremony that gives thanks to the gods and asks them to make the building durable and safe.

A traditional Japanese interior features a multitude of partially-screened, geometrically-arranged rooms with sliding doors that can be opened to create large spaces or closed to create private rooms. The translucent paper walls between the rooms allowed people to see shadows in the next rooms but not clearly see what was making the shadows.

The most expressive element of Japanese architecture is the roof, which tends to hang over the building like a shaggy wig and stress its smallness and horizontal plane. "The beauty of the building is most conspicuously the beauty of the roof, with its curves and sweeps and sculptural modeling," Boorstin wrote. "The styles of Shinto architecture, then are distinguished by their roofs, and the hierarchy of Japanese building is fixed not by their height but by their roof design."

The roof in a traditional Japanese structure is made of heavy timbers placed at right angles, and the sheer weight of it is what keeps structure in place. Trusses were rarely used until Japanese architecture was Westernized and even today Japanese engineers say that the heavier the roof is the more stable the structure is because Japanese buildings rest on columns at ground level instead of deep foundation so they can sway and bounce in an earthquake rather than buckle and collapse. A heavy roof holds the structure together and stabilizes the swaying.

Many traditional structures such as castles are built without nails. Instead the use various kinds of joinery and tongue ad groove construction.

Japanese Wood Architecture Construction Techniques

Japanese carpenters have traditionally lavished as much attention on the frames of their buildings as Westerners gave to their furniture, partly because Japanese shrines and houses have traditionally had very little furniture. Before hand-operated power tools were introduced to Japan in 1943, the Japanese carpenter’s tool chest contained 179 items, mostly wood-working tools. Japanese and Asian carpenters tend to saw and plane towards the body rather than away from it as Western carpenters do and and sometimes maneuver around the outside of tall structures on poles rather than Western-style scaffolding.

Traditional Japanese wood structure have few nails. Early European visitors to Japan were so impressed by the perfect fit of the swallow-tail joint at the corners of doors and windows they thought they must had been produced by magic.

Japanese carpenters and architects use their skills not decorate wood surface but rather to maximize the effect of unadorned wooden surfaces. Variations are made with different woods, grains and finishes. In Japanese lumberyards, pieces of wood are not piled in big stacks as they are in Western lumberyard, rather they are organized by color and grain. Cut logs are sometimes tied together in the positions they occupied on the living tree.

There are no textbook on shrine and temple carpentry. Skills are passed down through the apprenticeship system.

Japanese Architecture, Wood, Earthquakes and Fire

It had traditionally been thought that one of the main reasons why wood was more dominant in Japanese architecture than stone is that wood structures were less vulnerable to earthquakes that stone buildings, which topple over easier. But this is not always the case. Wooden structures are often destroyed by earthquakes, plus they are generally more vulnerable to fire and typhoons than stone buildings. The stone castles built on Osaka Nagoya and other places to fend off the threat of European firearms, often survived earthquakes better than wood temples and shrines."

Providing a better explanation for dominance of wood, Edward Morse wrote in 1885, "The Japanese house answers admirably the purposed for which it was intended. A fireproof building is certainly beyond the means of a majority of these people, as indeed it is with us; and not being able to build such a dwelling, they have from necessity, built a house whose very structure enables it to be rapidly demolished in the path a conflagration."

"Mats, screen partitions, and even the board ceilings can be quickly packed up and carried away," Morse wrote. "The roof is rapidly denuded of its tiles and boards, and the skeleton framework left makes but slow fuel for the flames. The efforts of the firemen in checking the progress of a conflagration consist mainly in tearing down these adjustable structures; and in this connection it may be interesting to record the curious fact often times at a fire the streams are turned, not upon the flames, but upon the men engaged in tearing down the building!"

Gojunoto is an earthquake-resistant pagoda erected in 1407 in Nara. The five stories oscillate in opposed phases when there are tremors, which keeps the structure from breaking apart. There is no evidence of the structure ever collapsing. The same techniques are used in modern buildings. The Yasaka Pagoda in Kyoto has survived more than five centuries of earthquakes. During a tremor the entire building sways as each story moves independent around a central anchoring pillar. Scientists are now studying the pagoda for clues on making modern buildings more earthquake-resistant.

Japanese Architecture and Weather

Traditional houses were built to deal with summer heat more than winter cold under the understanding that residents could put on layers of clothing in the winter. They were built of light materials — wood, bamboo, straw and paper — which provide terrible insulation but allow breezes to enter, air to circulate and heat to escape. In the old days some houses were so cold in winter that children went outside to play to get warm.

Some Japanese buildings have been constructed to respond to changing weather conditions. The Shosoin Temple, for example, the imperial treasure repository at Nara, has a roof made up of triangular timbers that expand during wet weather to protect the interior from rain and shrink during hot, dry weather to allow ventilation.

Houses and deep projecting roofs to offer protection in heavy monsoon rains. During the hot and humid Japanese summer, the Japanese like to keep cool by creating the illusion of coolness with the sound of running water and wind chimes that sound during the slightest breeze.

Traditional Japanese Building That Survived the Full Force of the Tsunami

In Ishinomaki, Miyagi Prefecture a century-old storehouse somehow survived the March 2011 tsunami, will be preserved with the support of building experts and enthusiasts across the country. The two-story storehouse, which was built in the year following the 1896 Meiji Sanriku Earthquake, is in the Kadonowaki district, about 500 meters from Ishinomaki Bay. The structure's characteristic feature is its namako kabe-style outer walls, which are covered with square tiles with joints protected by plaster. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, October 26, 2011]

According to its owner Eiichi Honma, 62, the tsunami washed away Honma's house and another storehouse on his land. The storehouse that survived had part of its outer wall damaged by destroyed houses and cars carried by the tsunami, and its first floor was flooded. However, it withstood the disaster relatively well, probably thanks to repairs to the reinforcement bars of the outer wall last year.

Development of Japanese Wood Architecture

Stone construction had been around for a long time in Japan, where sophisticated techniques were used to make stone bridges and tombs. But despite this, there is not one example of a surviving ancient Japanese building made of stone.

"The precocious development of Japanese metallurgy may help us understand their early uses of wood," writes Boorstin. Stone can be fashioned with stone, while woodworking and wood construction requires tools made of iron. Iron tools, based on prototypes brought over from the Asian mainland, were widely in use when Japanese architecture began in the primitive Yayoi era (300 B.C.-A.D. 300).

Another important factor that shaped Japanese wood architecture was the abundance of cypress trees in Japan. Cypress is a soft wood with grains running straight along the length of the tree, which it makes it easy to cut into timber. Early Japanese carpenters didn't even develop cross cut saws or planes, which are necessary to fashion woods with uneven grains. Cypress also has an appealing texture and fragrance, which make ideal for unadorned wooden surface.

By the 16th century the typical Japanese house had post-and-beam construction and elaborate joinery. The floor was raised above ground, its post resting on foundation stone, which allows the structure to bounce in the event of an earthquake. This style of house is still dominant in rural areas.

Traditional Japanese Homes

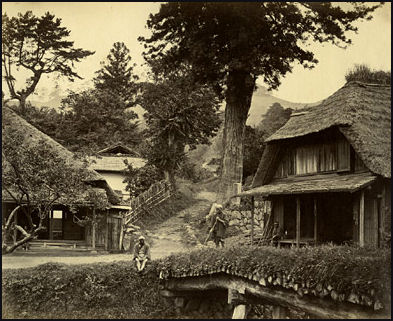

rural house in the 19th century Influenced by Zen Buddhism, the traditional Japanese home is simple and austere yet elegant. Common features include a fluid floor plan created by movable screens and the use of indigenous woods, straw, bamboo and paper. Large homes have courtyards surrounded by walls for privacy and protection against the prying eyes of tax collectors.

Types of traditional homes include thatched minka houses, samurai residences, teahouses, townhouses, traditional inns, mountain refuges and Haokone retreats. Kuri are traditional storehouses. The are recognizable by their thick white plaster walls. which were designed to protect the valuable supplies inside from fires.

Unique styles of Japanese architecture took shape in the Heian Period (794-1185). The mansions and homes built during this period had elaborate receiving rooms, sculptured gardens with huts, and thatch roofs with Japanese cypress tree beams resting on wooden pillars and beams. The interior had wooden floors with fixed room dividers. Single-leaf and folding screens, tatami and other light materials made it possible to define the living space freely.

The traditional Japanese house as we know it today has its origins in homes of rich farmers in the early Edo Period (1603-1868) and were built with tools and methods imported from Korea and China for building palaces and temples. The interior had wooden floors with fixed room dividers.

In urban areas, the Japanese fascination with the new and the urge to redevelop wins out over efforts to preserve the old. Many traditional houses have been lost because their owners couldn’t pay inheritance taxes — which can be as high as 75 percent of the value of the property — and were forced to sell.

Books: “The Japanese House: Architecture and Interiors” by Noboru Murata and Alexandra Black (Tuttle, 2001); “Japanese Homes and Lifestyles: An Illustrated Journey Through History” by Kazuya Inaba and Shigenobu Nakayama (Kodansha International, 2000)

Design of Japanese Houses

The interior of Japanese houses in the past was virtually open, without even screens to partition off individual spaces. Gradually, as more thought was given to particular areas and their functions, such as eating, sleeping, or dressing, self-standing screens (“ byobu”) came into use. “ Shoji “and “ fusuma”, which are still found in many homes, came afterward. Though they serve poorly as sound barriers, they do provide some privacy and can be removed to open up the entire space (except, of course, for the columns that support the house). “ Shoji “also admit light. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The way in which Japanese view the interior and the exterior of the house is another key aspect of traditional design. Instead of seeing the inside and outside as two distinctly different environments, they are thought of as being continuous elements. This concept is embodied in the Japanese veranda (“ engawa”), which acts as a kind of transition space from inside to outside the house. The “ nure-en”, which is fixed to the side of the house and gets wet when it rains, is a variation of the “ engawa”. From an aesthetic standpoint, the traditional house is designed for people who are seated on the floor, not standing. Doors, windows, and alcoves are placed so that both artwork in the house and the garden outside can be viewed appropriately from a sitting position.

“Despite the changes that modernization has brought to the style of houses, the traditional Japanese style has not vanished. Even in the Westernized houses, it is still usual to find a room whose floor is covered over with “ tatami”, and it is still the custom for people to remove their shoes before entering the house.

Thatch-Roof Houses and Machiya Houses in Japan

machiya house The charming-looking, giant, multi-storied, thatch-roof minka farmhouses are designed on utilitarian principals for large extended families with 40 or more people living on the top floors, domestic animals kept on the bottom floor and mulberry-leave-munching silkworms housed in the upper gables. Heat and light are supplied by a fire made in a central fireplace in the floor known as a “irori”. A lack of windows and a lot of make the interior resemble a cave. The best place to see traditional thatched-roof homes is Shirakawamura. The thatched-roof houses there are called gassho-zukuti, which refers to the fact they look like praying arms.

Built through a communal effort, gassho-zukuti are usually made of unpainted boards and waddle-and-daub walls without using a single nail. The steep praying-hands roof are designed the way they area or shed the heavy snows that fall on them in the winter. The name also indicates how devout the local people are. Most are followers of the Jodoshinshu sect of Buddhism.

The thatched roofs can be up to a meter thick and are made hand woven from thick reeds that come from communal grasslands. They are woven into matts that are tied on to the beams of the house by straw ropes. No nails are used. Inside the houses it is very dark. The roofs extend almost all the way to the ground and windows are only at the front and back of the houses. The large houses are four stories high and included spaces for raising silk worms.

The thatched roofs are replaced every 30 or 40 years, with work usually being done in April. The work has to be done quickly so the house is not damaged by rain. As many as 500 people take part in replacing a single roof. Some people stand on the roof beams and put the thatch in place while others hand the thatch up to them. With so much labor involved, the cost of doing a single roof can be $200,000. About three or four houses are reroofed every year, with the generous Japanese government absorbing of the costs.

In the old days villager maintained communal grasslands by annual cutting and burning to provide grass for roofs. The communal grasslands that supply the thatch are disappearing. Many have been plowed over for farms. The roofs and warehouses provide a habitat for raccoons, tanukis, rat snakes, geckos and lizards.

Traditional wooden townhouses found in Gion and elsewhere in Kyoto are called machiya. A typical one is six meters wide and 30 meters deep, has six tatami mat rooms, and is worth about $420,000. Many have lattice windows, stripped beams, Older unrestored ones have dirt floors and mushikomado windows framed by thick clay. They are designed to let cool breezes in during the summer. Today there are only 30,000 of them left (compared to 600,000 modern homes). Many were built in merchants in the Edo period. Today, preservationists are trying to keep these from being turn down.

“ Udatsu “ is an architectural feature of some Edo Period (1603-1867) homes in which thick layers of plaster were placed between upper floors to prevent fires from spreading. Although originally used to protect the community it became a decorative feature when fires posed less of a threat. The Japanese expression “can’t build udatsu” refers to those who are unsuccessful in their careers, the implication being that success in some ways is measured by having a beautiful house with udatsu.

Features of a Traditional Japanese Home

A traditional Japanese house today is made of wood and has “tatami” mat floors (floor coverings made of two-inch thick pressed straw, covered panels of tightly woven reeds), sliding shoji doors, wooden walls, lacquer doors, clay walls, coffered ceiling, sliding doors, a tile roof, lath-and-plaster walls, wood or metal rain shudders, and “tokonama” (display alcoves).

The Japanese invented sliding doors and sliding walls. Traditional houses have heavy paper sliding partitions that separate one room from another and can be pushed wide open or removed to create a single large room. Some homes have thick winter walls are can be replaced with thin summer ones. Windows facing the outside are often glazed and have grills and curtains so people can't see in

The “tokonoma” is an alcove in a traditional Japanese home intended for displaying a flower arrangement, a work of Zen-style art or a calligraphy scroll. Many modern homes are built without a tokonoma. The “genkan” is the traditional threshold, entrance area, where people leave their shoes.

Many homes have small Shinto and Buddhists altars. On visiting a Japanese home, one of the first things a host or hostess often does is show their guests pictures of living family members and dead ancestors on the Buddhist altar that is often in or near the tokonama.

The Japanese traditionally would speak to guests in the entrance hall or else show them to a reception hall or living-room-dining-room area. It very unusual for a visitor to come in the kitchen or the bedrooms and have a look around the house.

Many traditional Japanese homes have “shoji” (sliding paper screens) instead of walls. One Japanese artist told National Geographic that shoji creates a "good feeling" because "behind the shoji screen we cannot really see you, but we can know your actions, whether or not your are lively." Shoji windows infuse traditional homes with a soft natural light. "The best condition of paper is between eye and light," one papermaker said. "I can feel the life of the fiber. I can hear it. Perhaps we respond because of our own veins and arteries. We are knitted and connected, like the fiber."

Japanese Tea Rooms

In the Ashikaga Period (1338-1573), the Japanese upper classes considered it a pleasure to sit in a quite room with friends, separated from the worries of life, and listen to the soft sound of water boiling. Members of the aristocracy created special tea rooms in their palaces or tea houses in their gardens that looked simple in appearance but were actually created with a careful eye for detail. Daimyo held important meetings in tea houses that were set up to display their wealth.

The idea of the traditional tea ceremony cottage was to create an atmosphere of calm and meditation. Tea cottage designed by the great 15th century architect Senno Rikyu (1522-1591) were small and contained a bamboo ceiling, bare walls, sliding doors covered with snow-white translucent Japanese paper, and pillars made with wood still containing their bark. The only adornment was a hanging scroll will calligraphy or a flower arrangement in the “tokonoma”, an alcove in a traditional Japanese home intended for displaying a flowers or art.

The goal was to create a facsimile of a hermit's hut with a sense of “wabi” (quiet taste) and “shibumi” (sobriety). Hedges, stepping stones, a hand-washing basin and stone lanterns were placed on path to prepare one's spirit for the ceremony.

Image Sources: 1) Illustrations and diagrams, JNTO; 2) Pictures: Ray Kinnane (tea house, small shrines), Visualizing Culture, MIT Education (old village), Nicolas Delerue (modern Traditional house), on mark productions (Torri gates), Japan Visitor (machiya houses).

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013