SHINTO SHRINES

small Shinto shrines Sanctuaries for kami, or shrines, are called “jinja”. These usually consist of a building surrounded by trees. Most Shinto buildings are shrines (a sacred place for praying) not temples (places of worship). Temples in Japan are usually associated with Buddhism.

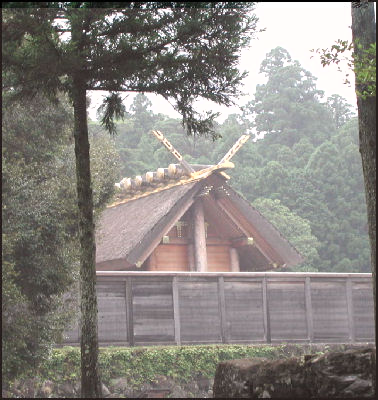

Classical Shinto shrines were not built to dominate nature and leave the observer awestruck, as many Western cathedrals were intended to do, rather they were built to harmonize and fit in with their natural surroundings. Shinto shrines are usually small in size and sometimes are so ensconced in trees they are difficult to see.

There are around 80,000 Shinto shrines in Japan. Almost every neighborhood has one. Most shrines have associations with specific gods and kami. But these are not fixed. It is not unusual for shrines to add new gods to address the needs of followers.

In the early days of Shintoism there were no Shinto shrines. Worshipers gathered and performed simple rites near sacred objects such as “sakaki” trees (now present at every shrine). The earliest Shinto shrines were sacred places marked off with special ropes (“shimenawa”) and strips of white paper (“gohei”). Fences and torii gates were introduced later. Ropes, white paper and torii gates are now common features of all shrines.

Shinto shrines come in various shapes and sizes. The architecture of most of them is believed to be based on wooden storehouses and dwellings from prehistoric times. Shrines that adhere strictly to architecture of these old buildings are known as "pure" style. The best examples of the "pure" style can be found at Ise shrine.

See Separate Article ISE SHRINE: ITS HISTORY, ARCHITECTURE AND RITUALS factsanddetails.com; SHINTO Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Shinto Shrines Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de Ise Shrine Isejinguisejingu.or.jp ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Wikitravel Wikitravel ; Izumo Taisha (20 miles west of Matsue) is the second most important Shinto shrine after the one in Ise. Wikipedia Wikipedia Japan Guide japan-guide Shimogamo Shrine UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website Kamigamo Shrine Kamigamo Jinja site kamigamojinja.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website Fushimi Inari Taisha Shrine (Inari Station on the JR Nara line) is the main shrine of more than 30,000 Inari Shinto shrines scattered throughout Japan. Kasuga Taisha Shrine (in Nara Park) Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Japan Guide japan-guide.com ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website

Purpose of Shinto Shrines

Shrines are mainly places where people can pray. Sometimes ceremonies such as wedding and milestone events for children are held at them. They are visited mostly on certain holidays or by people who want something.

Many have specific purposes. There are shrines for pregnant women who want a safe delivery, ones for fisherman to return safely from the sea and even ones for achieving sexual gratification. Homes and offices have small Shinto shrines to ward off evil spirits and protect the building from fires, earthquakes and typhoons. Most Shinto shrines are regarded as dwelling places of the Sun Goddess.

Shinto shrines are constructed according to sacred principals. They usually face south and sometimes to the east, but never to the north and west, which are regarded as unlucky directions according to the Chinese principals of “feng shui”.

Sacred Groves in Japan

Sacred groves are protected trees surrounding Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. They range in size from a single trees planted alongside stone statues to large forests preserved behind major shrines and temples. It is thought that original Japanese shrines were simple groves of trees, with kami dwelling in the grove itself. There are also hundreds of sacred mountains and sacred water sites — ponds associated with water deities, wells linked to the Buddhist monk Kukai and waterfalls thought to be inhabited by dragons and deities such as Fudi Moo.

Sacred groves usually have very tall, old trees — often cedar trees. If you see a stand of tall trees there is a good chance that it is a sacred spot. Sacred groves are often situated near crossroads or village entrances for local guardian spirits. Some also regard them as portals to Yomi, the land of the dead, which is connected with the myth of creator god Izanagi seeking his wife Izanami in Yomi, after she scorched her genitals and perished after creating the fire kami. In some sacred groves phallic symbols made of stone or wood were raised to honor the union of guardian spirits and fertility gods.

Main Shinto Buildings

Within the shrine grounds is 1) the main shrine (“haiden”), a place of worship where people pray, usually located at the rear of the ground; 2) a main sanctuary (“honden”), a sacred place namely off limits to lay people, where the kami of the shrine is believed to dwell; and 3) a hut-like pavilion for purification, where people rinse their hands and mouth with water taken from a basin (“chozuya”).

Shinto shrines has virtually no images or idols but they do have symbols. The inner sanctuary of these shrines, most of which haven't been opened in decades, contain a bronze mirror, (representing the sun and the sun god), and the sword and the jewel (symbolizing those given to Jimmu, the first emperor) and little else. Only Shinto priest are supposed to enter this sanctuary.

The main sanctuary is generally composed of front porch, where people pray, with a rope, a bell and a collection box. Beyond the porch is a small hall, where Shinto priests perform rituals and blessings, particularly on New years Day

Features of Shinto Shrines

Features of "pure" style shrines include natural wood columns and walls (as opposed to painted red and white ones), thatched roofs, horns (“chigi”) that stick out from the top of the roof, gabled ends, short logs (“katsuogi”) that lay horizontally across the ridge of the roof and free-standing columns that support the ride of roof at the ends.

Most shrines have elements of Chinese temple architecture that were incorporated into the shrines after Buddhism was introduced in the 6th century Features of "Chinese" style shrines include painted red and white columns and walls, tile roofs, Chinese-style upturned eaves, and detailed carvings and ornamentation below the eaves.

Special ropes and hanging tassles (“shimenawa”) and strips of white paper (“gohei”) date back to ancient times when they were used to mark off sacred places and ward off evil spirits. Below some shrines is the vestige of a sacred sakaki tree called the heart post. Many temples and shrines are filled with small shops selling religious items.

Shimenawa have traditionally been placed above the entrance of the main temples to mark it as a holy sight. They can be huge, The ropes can weigh 200 kilograms and the tassels, which resemble bundles of drying rice, can measure 1.5 meters in height. They are put in place with a crane.

The world's thickest ropes are at Izumo shrine, one of Japan's oldest shrines. Weighing six metric tons, the ropes are made twisted rice-straw strands as thick as a human being. Smaller versions of these ropes are kept at almost all Shinto shrines to ward of evil spirits. The world's largest rope is 564.3 inches long, 5 feet in diameter, and weighs 58,929 pounds. It was made of rice straw for the annual festival in Naha in Okinawa in October 1995.

The entrance of shrines are often guarded by stone statues of Chinese lions or Korean dogs. These menacing-looking statues usually appear in pairs. On one side of the gate one has an open mouth, spitting out good luck. One other side is one with a closed mouth, catching evil. Rice temples are guarded by foxes, clever animala regarded as a kami messengers and symbols of fertility.

Torii Gates and Stone Lanterns

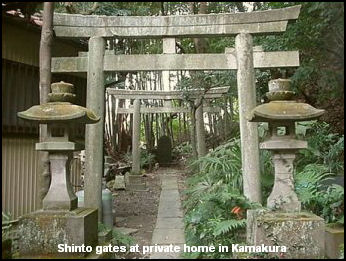

A red-orange “Torii” gate signal that you are about to entered a sacred place and should act accordingly. It consists of two upright pillars with two crossbeams at the top. Large shrines often have large torii gates, Large shrine grounds sometimes have many tori gates.

Ancient gateways were always made of naturally colored cypresses but entrances today may be composed of wood, stone, bronze or even concrete. A gateway painted red shows Chinese-Buddhist influence.

The pathway to a shrine is often lined with stone lanterns donated by worshipers. Stone lanterns are a fixture or many temples, pilgrimage routes and gardens and well as shrines. The design used in most lanterns originates from Korea. Some stone carvers regularly visit South Korea to get inspiration and gain insight into how the originals were created.

Most stone lanterns today are made by machines but some are still made by craftsmen using traditional manual techniques following images in their mind. Quality ones are made with capstones with cylindrical cores that hold the parts of the lantern together lightly even during an earthquake.

Craftsmen use a wide range to tools to shape the stone, including simple hammers and chisels. Lines are drawn with ink in the parts of the stone to be carved. After they are carved lanterns are exposed to rain and wind for at least three years so the gain the characteristics of wabi, or profoundness.

Shinto Priests and Virgins

There only 25,000 Shinto priests working at Japan’s 80,000 Shinto shrines. About 8 percent of them are women. An Australian woman, Caitlan Stronell, serves as a priest at a small shrine in western Tokyo. The main duty of Shinto priests is to perform purification rituals and ceremonies. Priests receive a few thousand yen for doing rituals. Most are only part timers.

When a priest perform his duties he wears a blue and white robe and a tall thin black hat. Sometimes he wears an elaborate silk robe. A typical priest in a small shrine attends regular, monthly Shinto rituals and helps senior priest preside over weddings, funerals and other ceremonies. It is possible to become a priest after attending a five-day training program.

The priest are assisted by female shrine attendants and ceremonial dancers known as “miko” (meaning "god's child"). In the old days they were required to be virgins and their duties were not all that different from those of the vestal virgins in ancient Rome: they were often intermediaries who were possessed by gods and passed on their messages to priest and people. Foreign women have served as miko Older women are looked down upon because they are not consider pure like virgins are.

The “yutate” (“immersion in hot water”) ritual is often performed by miko. In it a miko symbolically scoops nectar from the land of the kami and place it into a wooden bowl and then raises the bowl over her head and fills it with hot water and pass to a priest, who offers the bowl to kami on an altar in the inner shrine. The “kagura” dance”in which miko twirl around a couple times and wave branches or white paper pom poms”has its origins in shamanist trance dances. The miko at Ise shrine, specialize in dancing and praying. They need recommendations from their high schools and have to demonstrate they have some musical ability to be selected.

These days mikos are mostly high-school-age girls who wear white blouses and traditional skirtlike vermillion pleated pants. They do sacred dances at ceremonies and wedding, make offerings, clean the shrine, and sell good luck charms and other items. One miko told the AP, "My day starts with cleaning and ends with cleaning."

Shinto Rituals

In ancient times, Shinto rituals were divine communication ceremonies in which female shaman performed ecstatic dances. In a state of kami-possession they communicated with kamis and asked them to do such things as bless a child, help someone who was sick or insure a good harvest.

Shinto priests sometimes perform exorcism and purification rituals for new cars by opening up the doors, the hood and the trunk, saying some words and shaking “haraigushi””pom-poms made from branch of a sacred sakaki tree with white linen or paper steamers attached”as a symbol of purification. When asked why he uses the pom poms, one priest told National Geographic, "Demons don't like paper's hissing noise." Similar rituals are held for at building sites and new buildings. Some Shinto shrines will even purify credit cards and telephone cards for ¥1,000.

A typical large urban Shinto shrine has 430 ceremonies performed at it every year. During a “ yakubarai” ceremony participants are given “shimenawa “, a straw rope decorated with strips of paper, to break a jinx. A traditional Shinto blessing for a new construction project features a white-robed priest waving evergreen branches in front of a table laden with dried fish, while the people assembled bow their heads.

Most Shinto ceremonies are deeply connected with agriculture, especially rice farming, which according to Japanese mythology was given to people by a deity from the plain of high heaven. The importance of the rice harvest to Shinto can be seen each February when most shrines offer prayers for a rich harvest in the coming season.

Shintoism also has links with “matsuri” (festival), “misogi” (water purification), tug-of-wars, archery, sumo, and “gagaku” (scared music).

Ritual Dance

The oldest known dance in Japan is the “kagura”, a ritualist dance that has its origins in shamanist trance dances and is still performed by young girls in Shinto shrines today. Written about first in the 8th century “Kojiki” (Chronicles), kagura now describes a number of different dances and rituals performed throughout Japan. What separates them from folk dances performed in other countries is that they still contain a religious element. [Source: Encyclopedia of Dance]

Kagura incorporates elements of shamanism, animism, emperor worship and veneration of nature and fertility and is said have been first performed by the goddess Ame-no-Uzume. The word kagura is probably derived from an ancient contraction for “seat of the deity.” In its earliest forms it was a ritual performed by shaman and shrine virgins trying draw gods out of natural or ceremonial objects.

Most modern kagura dances have two parts: 1) a series of purification rituals used to invoke the gods; and 2) movements intended to entertain the spirts that have been invoked. Some kagura are performed in shrines by miko. Others are essentially local dances performed in honor of local gods. These are often performed to the music of pipes and drums at shrines and festivals and are performed by dancers in humorous masks and bright colored kimonos. Some of these dances use lion masks and involve boiling water and sprinkling it while masked dancers dance. There are special kagura performed for the Emperor.

The dances performed at the flower festival today in Aichi prefecture are regarded as kagura. Dancers gather on an earthen dance floor around a cauldron with water that boils through the night. After the spirits are invoked, dancers in specific age groups perform a series of dances, some with masks and some without. Towards the end of the night water in the cauldron is sprinkled on the audience as a form of purification. Towards dawn dancers in lion and devil masks appear. At dawn dancers representing fire and water emerge and restore order and close the festival.

Shinto Purification Rituals

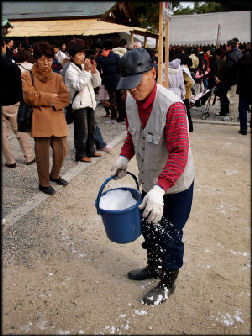

spreading puifying salt Many Shinto rituals revolve around purification and purging pollution, often through ritual ablution, the scattering of salt and the shaking of sakaki trees branches with white paper strips. Among the earthly offenses listed in a book of ceremonial codes, dated to A.D. 927, that can be remedied through purification rituals are the “cutting the living skim, cutting the dead skin, being an albino, sufferings from growths, a son’s cohabitation with his own mother, a father’s cohabitation with his own child...cohabitation with animals, calamities caused by crawling worms.” The spilling of blood has traditionally been looked down upon not because it was caused by an act of violence but because it was dirty and impure.

Sakaki tree are sacred in Shinto. Sprigs with bright green leaves, often adorned with small strips of white paper, are often left as offerings at Shinto Shrines. Branched have been used for centuries in Shinto rituals. In the Japanese creation myth the Sun Goddess is lured of a cave with a variety of items placed on a sakaki wood altar. A member of the tea family, sakaki are small evergreen trees with small flowers. They are believed to have been selected in ancient times for their sacred role because they grew well in forest clearings where pre-Shinto rituals were held.

In the old days there were three primary types of ritual purity: 1) abstention and withdrawal, the avoidance of a number things, only required of priests: 2) rituals for accidental defilements, including women experiencing menstruation, practiced by laymen; and 3) paying purification, traditionally invoked for more serious sins and often manifested in the paying of a fine to a kami.

During formal purification ceremonies, which are usually conducted on New Year's Day, participants have scared “sakaki” branches waved over their head by a priest or miko; drink some sacred rice wine called “miki”; perform a ritual prayers and partake in a symbolic feast; and offer some money (usually $100 or more). People that offer big money get their names placed on special plaques that vary in size according to the amount of money given.

Purification is also a key element of secular life and it has been for some time. A Chinese visitor to 8th century Japan wrote: “When funeral ceremonies are over, all members of the family go into the water together to cleanse themselves in a bath of purification. When they go on voyages across the sea, they always chose a man who does not arrange his own hair does not rid himself of fleas, lets his clothing get dirty as at will, does not eat meat and does not approach women. This man behaves like a mourner and is known as a “fortune keeper”. If the voyage turns out well, they all lavish slaves and other valuables on him. In case there is disease or mishap, they kill him, saying that he was not scrupulous in his duties.”

The Daimokutate Shinto rituals of Nara Prefecture were added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2009.

Seasonal Shinto Rituals

In ancient times, there were two main festivals each year: a New Year's festival in the spring in which people prayed for good harvests and kimono-clad girls planted rice and danced while musicians played; and an autumn festival after the harvest in which shrines with symbols of gods were paraded through the streets on the shoulders of men. Festivals to ward off disease were sometimes held in the summer, the time of the year when epidemics most often occurred.

The annual rituals and ceremonies at the Ise temple are intimately bound with nature and the seasons. The rice for the sake and cakes used in the renewal celebration comes from the same seven-acre paddies which has been used for thousands of years. The field is irrigated with water from Isuzu River and the soil is fertilized with dried sardines and soy bean patties.

In April in Ise trees are cut down to make hoes for planting seeds. In June men and women in traditional white and red costumes transplant seedlings to the music of sacred flutes and drums and then dance and pray for a good harvest at the shrine honoring the deity of the rice paddy. [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Creators"]

Nagoshi Oharate is a summer purification ritual held on June 30 for purging sins and impurities accumulated over the past six months and for bringing good health in the coming six months. At some shrines priests pass through a large grass hoop and throw a human effigy into a river at night.

Akiba Shinto shrine conducts a firewalking ritual believed to promote health. At some Shinto shrines people douse themselves on cold water, battle each other for lucky sticks, and carry huge shrines.

Matsuri

Many big, rowdy Japanese festivals revolve groups of people carrying portable Shinto shrines though the streets or up hills to major shrines. Describing one such event, a travel writer wrote: "The shrine teetered at the top of the steep staircase as its porters struggled with fear and the very real possibility that it could crash and slide out of control down the steps and into the fire. Suddenly the mikoshi careered downwards, for a few seconds apparently out of control, but was soon brought to a halt by the struggling heaving porters." See Festivals

“Matsuri”, a Japanese word that means “to entertain” and “to attend to,” is used to describe both festivals and worship at Shinto shrines. It also implies respect duty, and willingness to listen to and serve “kami” (“spirits or gods”) and brings their power to everyday life. Most matsuri give honor and thanks to the kami associated with the shrines used in the festivals.

Matsuri are seen as religious occasions for the parishioners of a local Shinto shrine to commune with the god of that shrine and wish for a plentiful harvest. These events often involve purification rites, offerings, sharing of food carried out by priests and a procession of miloshi (portable shrines) and decorated floats by parishioners with the goal of bringing the attention of the gods to the needs of the people.

Shintoism and New Year's Day

On New Year's Day many, most Japanese visit a Shinto Shrine and pray for good luck in the coming year, place items from the old year in a bonfire, and leave offerings of rice, vegetables and wrapped bottles of sake. Some people dress up in kimonos or nice clothes. Sometimes small gifts are exchanged but gift-giving generally isn't a big part of the holiday.

At the Shinto shrine, people are blessed in Shinto ceremonies (costing about $50 to $100 per family) and wait in line to ring a small bell and pray, drink hot sake, eat mochi (chewy rice cakes), exchange greetings and gossip with friends and relatives, and buy sheets of paper (“ omikujo “) that has ones fortune for the upcoming year (See Superstitions) and special arrows. According to Japanese tradition bows and arrows have magical powers that can repel evil spirits. Pink paper lanterns hang from the trees on the shrine grounds.

When praying people toss some money into the offering box and say a prayer for a healthy and prosperous New Year. Many Japanese say that doing this makes them feel energized. The sake is usually free and offered to lift one’s spirits. Charms are available for specific tasks as well as for general purposes. They can be purchased for oneself, one’s family or friends or for a house, car, studies or pets. The previous year’s charms are sometimes tossed into a fire burning at the shrine.

As part of nationwide campaign to reduce dioxin pollution, objects such as amulets, prayers and arrows that have traditionally been burned in bonfires on New Year' Day and other holidays and festivals are now made from materials that don't produce dioxin when burned.

A record 99.39 million people visited Shinto shrines on the first three days of the new year in 2009. Meiji Jingu in Tokyo typically gets over a million visitors a day between January 1st and 3rd. To maintain ordered police or on hand and ropes are put in Palace to control the flow of human traffic.

In the first three days of 2009, Meiji Shrine in Tokyo received the 3.19 million visitors, the most of any shrine in Japan, followed by Shinshoji temple in Narita, Chiba Prefecture with 2.98 million. In 2008, 2.89 million visitors visited Indri Tisha shrine, dedicated to the god of harvests, in Kyoto. It took 12 employees five days to count all the money left at the 50 or so collection boxes at the shrine. In addition to cash offering people left lottery tickets and mochi rice cakes.

Shinto Customs and Symbols

Religious rituals and prayers are often said at home before a family altar called a kami-shelf (“kamidana”), on which are placed family pictures, photographs of the emperor and amulets from the Ise Shrine (the most important one in Japan) or another shrine. Many Japanese pray, make offerings to shrine tablets, and clap twice at the kami-shelf every morning and evening.

White is a symbol of purity in Shintoism. Priest and temple virgins usually dress in white and usually make offerings that are either white or wrapped in white paper. In some rare cases people wear white masks to avoid polluting the offerings with their breath.

White represents cleanliness in Japan. Taxi drivers wear white gloves and factory workers wear white uniforms to demonstrate how clean they work. Green represents safety.

Shinto practitioners believe kami come from beyond the horizon not from heaven. Prayers are directed towards the earth, where they kami live, and made for people who are living (prayers for the dead are made at Buddhist temples).

fortune slips

Shinto Good Luck

Special talismans are purchased at Shinto shrines to bring good luck and ward off evil spirits. They include arrows, small charms and votive plaques (“emu” or “ema”) which have a blank side on which people can write a wish or request.

In most Shinto shrines there is a wall covered with wooden ema that contain requests written to kami. Common requests include good luck in finding a marriage partner or having a child or success with a business or an important exam. The word ema mean “horse,” a reference to the old days when it was believed that horses were messengers for kami.

People usually make the ema themselves. They often have a horse and other objects on the front and their names and addresses on the back. Pictorial symbols are often used to express the request. A target with an arrow, for example, is a request to pass an exam. Images also often represent the kami the request is addressed to.

Fortunes (“omikuji”) are determined by selecting bamboo sticks from a box and choosing a fortune according to the number on the stick or simply pulling a folded paper from a box. Luck is classified into “dai-ichi” (great luck), “kicki” (good fortune), “sho-kichi” (middle good fortune) and “kyo” (bad luck). If you like your fortune you can keep it. If you don’t like it you can tie it to a branch on a tree on the shrine grounds.

Shinto Shrine Customs

praying at a shrine Japanese generally do not visit Shinto shrines once a week for a sermon like Western churchgoers. They are visited on holidays, as tourist attractions, as places to seek tranquility in crowded Japan, or when they need some advice or seek help from kami.

Japanese are required to wash their hands and mouth in a natural spring or rock-hewn pool before entering a shrine. Visitors to the shrine use a ladle made from bamboo to wash both hands and then pour water into a cupped hand to wash their mouth.

At the front of the shrine, worshipers usually toss a coin into a donation box, ring a bell (to tell them kami they are there), make two deep bows, clap loudly twice (to wake up the kami if they are sleeping), bow again and hold their head down as long as the prayer lasts.

Praying for money is considered disrespectful and selfish, but praying for a baby, good luck in business, a promotion or a good test score is okay. Shrine visitors often purchase a ema plaque (for around $6), write a message and hang it on the right side of the shrine on a sacred sakaki tree.

An early prayer performed at Ise went: “As you have blessed the ruler’s reign, making it long and enduring, so I bow down my neck as a cormorant in search of fish to worship you and give you praise through these abundant offerings on his behalf.”

Shinto Family Customs

Visiting a shrine has traditionally been something that a family did together. In the old days, shrines were often dedicated to the founder of a clan and were where his clan worshiped. When a child is taken to a shrine today it is not only seen as a sign of worship it is viewed as link with the community.

Japanese go to shrines to mark important milestones in their lives. Parents take their children when they are 30 days old or 100 days old and men and women go on their 20th birthday, when they are considered adults.

See People, Marriage, Weddings Marriage Ceremony.

Ise Shrine Christal Whelan wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The Shinto, Buddhist and Shugendo practice of misogi or spiritual cleansing through standing under a waterfall, or dousing oneself with buckets of bracingly cold water, derives from the deep desire to be united with the clarity and purity of water. Water by its very nature changes form according to the container in which it is placed. This quality suggested the Buddhist wisdom of the emptiness of form, and the social value of flexibility and a situational ethic over an unchanging stance for all occasions.”

Cold water ablutions are performed under a waterfall at the Shokoji Temple — a Zen Buddhist temple in Kawachinagano, Osaka Prefecture. In recent years the temple has found that many of the people that participate in the ritual are young adults who having trouble finding jobs and a direction in life.

Devises that capture the sound of water are found at many temples and shrines. “The sui-kin-kutsu is a musical instrument played by water as it drips into an overturned perforated bottle buried underground, wrote Whelan. “As droplets fall languorously through the hole, the bottle resonates like music from a dragon's chamber. The sozu, a miniature bamboo seesaw poised above a basin in a balancing act played by water alternately spilling from each end, Kyoto's version of a scarecrow. Its loud, rhythmical, and never-ending clacking characterizes the sound of summertime in the city.”

Image Sources: 1) small shrines, fortune slips, praying, priest and miko, salt spreding, Ray Kinnane 2) digrams of shrines and shrine features, JNTO 3) matsuri, Tori gates, Onmark Productions, 4) ritual, Photosensibility 5) Ise Shrine, Yamasaise

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2011