SHINTO

19th century Shinto priest Shintoism is an informal animist religion that honors ancestors, pays tribute to “kamis”, or spirits, and has traditionally had strong bonds with the Japanese state, emperor and culture. There are literally millions of kamis, most of whom are associated with the heavens or natural objects on earth such as trees and mountains. One of the most important deities is Amaterasu-omikami, the sun goddess, who, according to legend, gave birth to Japan's first ruler, Emperor Jimmu. Japan's present emperor is reportedly the 125th in an unbroken line of descendants of Emperor Jimmu.

Shinto has been around in a formal sense for over 1450 years, coexisting with Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism. With the introduction of the paddy-field system during the Yayoi period (300 BC--AD 300), the agricultural rituals and festivals that later became part of Shinto began to develop. The name Shinto is based on the Chinese character “Shin-tao” which roughly means "Way of the Gods." It is derived from Chinese words “she”, meaning “divine being? and “tao”, meaning “the way.” The term “shinto? was coined in the sixth century when Buddhism entered Japan so the two religions could be distinguished from one another.

Determining the number of Shinto followers in Japan is difficult because it is difficult to define exactly what a Shinto follower is. One survey counted 3.25 million Shinto followers while another counted 107 million. A survey that came up the figure of 85 million did so by counting the number of people that contributed to shrine festivals, something most Japanese feel obligated to do as much out of social duty as religious belief.

Shintoism has no founder, no official sacred scriptures, no fixed dogma and no concept of afterlife.On one hand it is very formal and organized. On the other hand it embraces a hodgepodge collection of folk practices, everyday beliefs and secret rituals. Fo many Japanese it is simply a “celebration of life, of all forms of life and the place of human beings in nature.” The absence of official sacred scriptures in Shinto reflects the religion’s lack of moral commandments. Instead, Shinto emphasizes ritual purity and cleanliness in one’s dealings with the “kami”.

Shinto is the national religion of Japan. Some call it a "patriotic cult" not a religion because its links to the founding of Japan and the Japanese Imperial family. Others see it as more of a community religious because of its emphasis on local shrines and local guardian gods. Some scholars insist that, like Confucianism, Shintoism is not a religion but rather a set of customs, rituals and beliefs related to ancestor cults and animism.

Shinto shrines in Japan are overseen by the Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honcho)

Links in this Website: RELIGION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO SHRINES, PRIESTS, RITUALS AND CUSTOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST GODS, TEMPLES AND MONKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ZEN AND OTHER BUDDHIST SECTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Book: “Shinto: The Way Home” by Thomas P. Kasulis (University of Hawaii, 2004); Websites and Sources: Religious Tolerance Pieces on Shinto religioustolerance.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Encyclopedia of Shinto kokugakuin.ac.jp ; Jinja Honcho, the Association of Shinto Shrines jinjahoncho.or.jp ; Buddhism and Shintoism in Japan A to Z Poto Dictionary onmarkproductions.com ; Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Texts Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; The Kojiki Google e-book books.google.com ; Academic Work on Kami (1998) kokugakuin.ac ; Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America tsubakishrine.org

Early History of Shintoism

The religion practiced in Japan during the Yayoi Period (300 B.C.-A.D. 300) was a form of animism and nature worship with no clear distinction between divine and human and nature and divinity. There were distinctions, though, between good and evil gods. Early proto-Shinto religions had shaman. Many female shaman are still active in Okinawa and northern Japan.

Shintoism appears to have developed out of an awe of nature, particularly the sun, the water, mountains and trees. By the Nara period (710-794), there were “kami” cults that believed in supernatural powers, mountain asceticism and mountain magic.

Shintoism doesn’t really have any religion texts like the Bible or Koran. The two more important texts in Shinto are the “Kojiki” (Records of Ancient Matters) and “Nihon Shoki “ (Chronicles of Japan). Both of these texts date back to the 8th century, and are claimed to be historical records, although they are filled with supernatural tales, legends and myths.

Chinese and Korean influences helped give Shintoism a structure and social and political organization and provided the notion that ritual went hand in hand with being a good human being and being a contributing member of society.

Shintoism has stubbornly hung on in the face of competition from Buddhism, Confucianism an other religions because it was able to coexist with these religions and remained popular with the masses in the countryside.

Animism

sacred tree Many regard Shintoism as a kind of animism. Animism refers to the collective worship of spirits and dead ancestors rather than individual gods. Derived from anima, the Latin word for soul, it was coined in 1871 by Edward Taylor to describe a theory of religion. Animism and ancestor worship are often closely linked. Animism is not the worship of animals.

Animism emphasizes a reverence for all living things. Many animists believe that every living thing and some non-living ones too — even trees and insects and things like special rocks and landscape formations — have a spirit. Commonly these spirits merge with other spirits such as a common river or forest spirit and a general life spirit. Some spirits are conjured up before a tree is chopped down or food is eaten to appease them. Others are believed to be responsible for fighting disease or promoting fertility. Animist spirits are often associated with places or objects because they were thought to live close by.

Many anthropologists believe that animism developed out of the belief in some cultures that natural spirits and dead ancestors exist because they appear in dreams and visions. Other anthropologists speculate that the idea of spirits developed among early men out of the concept that something alive contains a spirit and something dead doesn’t, and when something alive dies its spirit has to go somewhere.

Buddhism and Shintoism

The term Shinto was first used around the time that Buddhism was introduced in part to distinguish the indigenous religions of Japan from the imports from the Asian mainland. The way (to) in Japanese is the same as Tao in Taoism. It was fortunate that the brand of Buddhism that entered Japan was the Mahayana form, which tended to be tolerant and willing to accept new ideas and form bonds with other belief schemes.

Within Japanese Buddhism, Shinto was explained as a sort of local manifestation of universal truths and kami were integrated as local versions of Buddhist deities. Shintoism accommodated Buddhism by making Buddha a kami that originated from China and making kamis susceptible to the same cycles or death and rebirth that Buddhist believe occur to people. Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines were often built near one another. Buddhist sutras were recited to kami and kami were later regarded as incarnations of Bodhisattvas.

Buddhism has coexisted in Japan along with Shintoism for at least 1,400 years. Throughout most of Japan's history, Buddhism was a faith linked with the upper classes while a mixture of Shinto, animist and Buddhist beliefs were observed by ordinary Japanese. Buddhism is credited with making purity in Shinto an internal issue as well as an external one.

Ryobu, or Dual Shinto, is movement based on mutual respect between Buddhism and Shintoism. Originating in the 8th century, it borrowed ideas and doctrines from both religions and manifested itself through Buddhist relics placed in Shinto shrines; statues of Shinto deities erected in Buddhist temples; and the Emperor expressing his loyalty to Three Treasures of the Sun Goddess and promising to revere the teachings of The Buddha.

Temples for the Buddhist Tendai sect had so many Shinto elements they were described as “religious junkyards.” The Tendai believed that Buddhist deities were aspects of The Buddha, thus it followed that Shinto kami could be incorporated as aspects of The Buddha as well. The Shingon sect of Buddhism also incorporated Shinto elements.

In the Heian Period, ascetic Japanese holy men, known as “hijiri”, were thought of as Buddhists even though they wandered in the mountains in an attempt to attain superhuman powers and "ecstatic inspiration" and worked at Shinto shrines as shaman. Beginning in the 15th century there was a concerted effort to rid Shintoism of Buddhist and other foreign elements that gained momentum when Shintoism was transformed into a nationalist ideology in the 19th century.

Japanese Emperor and State Shintoism

Shinto symbols of the Emperor According to the Shinto creation myth, the first Japanese emperor was the son of the Sun God, and the islands of Japan were the first pieces of land created by the gods, and thus the center of the world.

The myth of the Japanese Imperial Family's divine origin has traditionally been a basic tenant of Shinto. After Meiji Restoration in 1868, and especially during World War II, Shinto was promoted by the authorities as a state religion (almost the same way that Islam is the state religion in Saudi Arabia).

The historian Ian Buruma told the Japan Times: “State Shinto was deliberately set up in the 19th century as a Japanese version of the Christian church.” The Japanese “were always looking for reasons to explain why the West was so powerful and Japanese thinkers in the 18th century came to conclusion that it all came down to Christianity: It was the church that tied people together and made them obedient to their leaders. So they concluded that what they needed was a national church, and that became State Shinto.”

Over time Shintoism was co-opted from it decentralized animists roots into a state-sponsored war religion. Ian Buruma has suggested that State Shinto was created by “grafting German dogma on Japanese myths. They shared military discipline, mystical monarchism and blood-and-soil propaganda about national essences.”

The Japanese constitution of 1889 declared the emperor sits upon "the throne of a lineal succession unbroken through the ages eternal" and pre-World War II Japanese student were taught that the emperor was a god. Shinto doctrines were taught in school; Shinto shrines were supported by the government; and religion and nationalism developed strong links.

End of State Shintoism

State Shintoism remained alive until the end World War II, when the Emperor told the nation in he wasn't a god and the constitution took away Shinto's official government support. Under American occupation, Shintoism was disestablished and its holidays were curtailed.

As part of the surrender agreement between Japan and the United States that ended World War II, the allies allowed Emperor Hirohito keep his throne but required him to renounce his semidivine status. In January 1st, 1946, Hirohito publicly denounced "the notion that the emperor is a living god" and rejected the idea that "the Japanese are a superior to other races destined accordingly to rule the world."

Nobel Prize-winning author One said one of the most momentous events in life was when the Emperor confessed after World War II that he was not a God. He, like other Japanese, had been taught in school that the Emperor was a indeed god and many believed that was the truth.

The end the State Shinto Cult left a lot of Japanese confused and cynical. Historian Ian Buruma wrote it a created a post-war spiritual vacuum that provided "fertile ground for all kinds of new cults and creeds...Most of them organized around a charismatic figures."

Shintoism Today

Today, Shintoism is viewed by many Japanese as a vehicle for expressing their links to their Japanese past and praying for good fortune. It exists mainly in the form of holiday visits to shrines, tying lucky strips of paper to bushes, ans the selling of amulets to Japanese and tourists. Its spirt invigorates arts and crafts.

Most of the money earned by Shinto shrines comes from ceremonies performed during weddings and the new year. Priests are typically paid about $50 to a few hundred dollars for a ceremony. Many shrines don’t even have priests and rely on community organizations to keep them going. They in turn rely on money given when making prayers, the sale of fortunes and religious objects and membership fees of around $10 a year by community members. Most of these who donate are elderly. As older people die off shrines have a hard time getting money from younger people.

Shintoism has collapsed as being anything meaningful in the eyes of many Japanese along with the Emperor. The inability of Shintoism to address modern problems and to be relevant is regarded as one reason why so many people turn to cult religions in Japan.

Four Categories of Shinto

Shinto is sometimes broken down into four major categories: folk Shinto, sectarian Shinto, Imperial Shinto and shrine Shinto.

Shrine Shinto involves general Shinto religious activities that can be seen in shrines across Japan. Folk Shinto does not have an organized religious body but is deeply rooted in folk culture in the community.

Imperial Shinto involves rituals performed by the Emperor. The most well-known ceremony is Niinamesai, a kind of thanksgiving festival in which offering from the first grain harvest of the year are given to deities in return for their blessings.

Sectarian Shinto, which has 13 sects such as Kurozumikyo and Konkoyo, is a more recent movement. These sects have their own sacred texts and were founded by specific people or groups of people from the end of the Edo period (1603-1867) into the Meiji era (1868-1912).

Shinto Beliefs

As we said before Shinto has no fixed doctrine, no founder, and no collection or canon of sacred texts. Unlike other religions that have a specific theology and doctrine, Shintoism is comprised mainly of myths of the origin of Japan and a series of ritual developed over time. The central religious acts are prayers performed by individual Japanese in more or less the same way, thus generating a shared set of values and attitudes that reinforced by the myths. It has been said that in Shintoism “correct ritual” is more important than “correct doctrine.”

One of the most noteworthy features of Shinto is its emphasis on intuitiveness, experience and faith not reasoning and theological principals. According to religious scholar Geoffrey Parrinder Shintoists "rarely ask questions" rather they "feel the reality" of their gods. "A direct experience of divinity and a sensitive experience of mystery," he wrote, "are for them far more important than an intellectual approach to doctrinal niceties." ["World Religions" edited by Geoffrey Parrinder, Facts on File Publications, New York]

Shinto encourages people to help one another, communicate, respect their elders and the spirits of their ancestors through Shinto ceremonies. Many rituals involve giving thanks with implication being that giving thanks will bring good things in the future. For Japanese taking control of their fate is a novel idea. There is a Shinto superstition that says if you ask "what if" questions they will come true.

Shinto Purity

Purifying water Shinto teaches people to have a deep reverence for nature. Tied with this is the concept of purity, which is central to Shintoism. There is an emphasis on spiritual and physical purity and cleanliness. Many ceremonies are acts of purification. The Japanese tend to see the world in terms of clean and dirty rather than good and evil. The Land of Darkness is the land of puterfectaion and pollution. The Land of the Sun Goddess is a place of light, purity, life and fertility.

By purification and ritual perfection man approaches the divine. During creation many kami are said to have come into being by purification or ritual purification. The purity that is referred to is mostly external. There not much mention of purifying internal or moral conditions. It not related to saving your soul. However purity ritual are expected to be accompanied by corresponding changes of the inner heart.

Purity and detachment from death are one reason why the capital of Japan was changed during the pre-Nara era and why the Great Shrine in Ise is dismantled and rebuilt every 20 years. It is also why salt is scattered in a house after a funeral; is placed beside wells and next to restaurants; and is tossed in the ring by sumo wrestlers before a match.

See Rituals Below

Kami

The closest thing to gods in Shintoism are “kami”, a word which is often translated as "god" or "gods," but whose realm meaning is closer to words and phrases like “upper,” “above,” “awesome,” “awe-inspiring,” “dreadful,” “superior and extraordinary beings,” “spiritual power that exists outside the ordinary world,” or “strange and mysterious power.”

One religious scholar defined kami as “anything whatsoever which was outside the ordinary, which possessed superior power.” Individual natural things have their own kami. Kami are important for dealing with the “musubi” (creative power of the universe).

There is a certain undefinable quality to kami. Japanese scholar W. G. Aston once wrote" "The Japanese people themselves do not have a clear idea regarding kami. They are aware of kami intuitively at the depth of their consciousness and communicate with the kami directly without having formed the Kami-idea conceptually or theologically. Therefore it is impossible to make explicit and clear that which fundamentally by its very nature is vague."

The Shinto revivalist Mtoori Noringa (1730-1801) wrote: “I do not yet understand the word kami. In its most general sense, it refers to divine beings on earth or in heaven that appear in the classic texts. More specifically, the kami and the spirits are abiding in, and worshiped at, shrines. In principal, humans, birds, animals, trees, plants, mountains, oceans, can all be kami. In ancient usage, anything that was out of the ordinary, or that was awe-sinpiring, excellent or impressive was called kami.”

Different Kami

There are hundreds of thousands of kami. Once somebody counted eight million of them. They reportedly dislike impurity and uncleanliness and like uprightness, honesty, sincerity and harmony and generally fall into two categories: ones associated with the earth and ones associated with heaven. Like pagan Greek gods, some kami have desires and personalities like human beings.

Kami come in a seemingly infinite variety. There are nice kami, mean kami, strong ones, weak ones. There are kamis for birds, beasts, trees, plants, seas, mountains, individual species of insects, stones, cypress trees, chrysanthemums, volcanic eruptions, and echoes as well as seven one for good luck. Strangely-shaped trees or extra large stones are said to possess extra powerful kami. Some outstanding people become kami and shrines are set up for them when after they die and communities pray to them as they would to other kami.

“Although the word “kami “can be used to refer to a single god, it is also used as the collective term for the myriad gods which have been the central objects of worship in Japan from as far back as the Yayoi period. The “kami “are part of all aspects of life and manifest themselves in various forms. There are nature “kami “that reside in sacred stones, trees, mountains, and other natural phenomena. There are clan “kami”, called “ujigami”, which were originally the tutelary deities of specific clans, often being the deified ancestor of the clan. There is the “ta no kami”, or god of the rice paddies, who is worshipped at rice-planting and harvest festivals. And there are “ikigami”, who are living human deities. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The “kami “that most resemble gods in the Western sense are the heavenly divinities who reside on the Takamagahara (High Celestial Plain). They are led by Amaterasu Omikami, the goddess worshipped at the Ise Shrine, the central shrine of Shinto. Partly in response to the arrival of highly structured Buddhist doctrines in Japan in the 6th century, pervasive but previously unorganized native beliefs and rituals were gradually systematized as Shinto. The desire to put the legitimacy of the imperial lineage on a firm mythological and religious foundation led to the compilation of the “Kojiki “(“Record of Ancient Matters”) and the “Nihon shoki “(“Chronicles of Japan”), in 712 and 720, respectively. In tracing the imperial line back to the mythical age of the gods, these books tell how the “kami “ Izanagi and Izanami produced the Japanese islands and the central gods Amaterasu Omikami. The great-great-grandson of Amaterasu Omikami is said to be Emperor Jimmu, the legendary first sovereign of Japan.

Rice Paddy Kami

Ta no Kami is the Japanese word for rice paddy spirits. Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “The Ta no Kami cult is widespread throughout the country, and is at the heart of Japanese rural folk cosmology. The Japanese imbue rice with a sacred reverence and deep cultural significance that completely transcends the plant's nutritional and economic value as a food grain. It was rice, first brought here from the Korean Peninsula nearly 3,000 years ago, that transformed Japan from a land of scattered hunter-gatherers to a great nation. Gohan, the basic word for cooked rice, is also a general term for food or a meal. Even today, the Japanese people, despite their insatiable appetite for bread and noodles, still think of themselves as rice eaters. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, April 19, 2012]

“In most regions, the Ta no Kami are represented abstractly, with tree branches decorated with strips of paper, sometimes stuck into mounds of sand. In a restricted area of southern Kyushu, however, there is a tradition, dating back to at least the early 18th century, of carving unique stone representations, locally called Ta no Kansa. This tradition centers in Kagoshima Prefecture but includes a small portion of neighboring Miyazaki Prefecture as well.

“The statues here are very typical of this Kyushu style. Each wears around his head a thick cowl that is actually the prop in a clever illusion. Seen from behind, this cowl turns into the top of a potent male phallic symbol. In Japanese folk cosmology, the rice-paddy spirits are actually one and the same with the Yama no Kami, or mountain spirits, which are sometimes represented as phallic symbols.

“Yama no Kami reside in hills and forests all over Japan. They can be thought of as basic animistic spirits mingled with the departed souls of the local ancestors, which are believed to eventually rise into the mountains. In many regions, these basic protective spirits inhabit the mountains during the winter months, but come spring they move down into the rice paddies, turning into the Ta no Kami and watching over the precious crop until the autumn harvest is over, after which they return to the forested slopes. In Kyushu, the Ta no Kansa stones are placed on the dikes that surround and separate the paddies, and the villagers hold colorful festivals to welcome and petition the Ta no Kami in spring, and to see them off with great thanks in autumn.

Nature Worship and Sacred Mountains in Japan

Sacred Fuji mountain Unlike Christians which often views nature as evil, Shintoists views it as good and spiritual. Men and women are not seen as superior to nature but rather as brothers and sisters of all natural objects. Some of the nature kami have a human origin. According to one Shinto myth, purified ancestral spirits dwell for 33 to 50 years in a cemetery and then move onto mountains, where they become helpful kami that come down to the rice paddies in spring and return to the mountains in the fall. The forests, which cover two thirds of country, are also sacred.

Because they were the highest and biggest earth-bound natural objects around and other natural objects seemed dependent on them, mountains took on a special place in Shintoism and other eastern religions. Japanese have long regarded mountains as places used by heavenly kami to descend to earth and stations people went after they died before they moved on other worlds. Farmers worshiped mountain kami because they supplied water to make their rice grow. There were often specific gods for specific mountains as well as for the bases, lower slopes, upper slopes and summits of these mountains.

The Japanese once believed that Mt. Fuji was the center of the universe. The female deity of Mt. Fuji, known as Sengen-Sama, holds a high place in the religious hierarchy. Mt. Fuji boasts over 13,000 shrines and each year thousands of mantra-chanting pilgrims — with jingling prayers bells straw hats, pure white robes and white canvas mittens on their feet — ascend to the top of the mountain, stopping at its stations and traversing the rocky peaks around the carter. Some worshipers leave their sandals on the top of Mt. Fuji to raise its height.

According to an ancient folktale Mount Haku, another sacred mountain also known as Yatsu-ga-take, was once higher than Mt. Fuji. "Once the female deity of Fuji and the male deity of Haku (Gongen-sama) had a contest to see which was higher," the myth goes. "They asked the Buddha Amida to decide which was loftier. It was a difficult task. Amida ran a water pipe from the summit of Yatsu-ga-take to the summit of Fuji-san and poured water in the pipe. The water flowed to Fuji-san, so Amida decided that Fuji-san was defeated. Although Fuji-san was a woman, she was too proud to recognize her defeat. She beat the summit of Yatsu-ga-take with a big stick, so his head was split into eight parts, and that is why Yatsu-ga-take (Eight Peaks) now has eight peaks."

Mountain Pilgrims, see Buddhism, Yamabushi, Shugendo

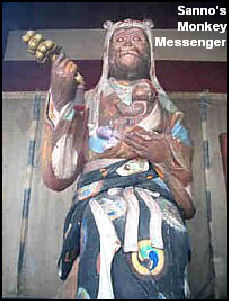

Image Sources: 1) tree and water, Ray Kinnane; 2) monkey kami, Onmark Productions, 3) Creation myt Tokyo Nation Museum; 4) priest, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2022