BUDDHISM IN JAPAN

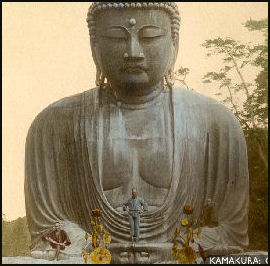

Great Buddha of Kamakura Buddhist funeral and ancestor rites are widespread in Japan. Most funerals are conducted by Buddhist priests, and many Japanese visit family graves and Buddhist temples to pay respects to their ancestors. Although regular attendance at Buddhist temples is rare, partly because many Buddhist sects do not observe communal worship, there were nearly 75,000 temples and 204,000 priests in the early 1990s. Both Buddhist and Shinto priests marry, and sons often inherit responsibility for their father's congregation when he dies. The Nichiren School, based on belief in the Lotus Sutra and its doctrine of universal salvation, is the largest sect in Japan. [Source: Library of Congress, 1994 *]

The Japanese name for The Buddha is Shaka. Japanese Buddhism is very similar to Chinese Buddhism. It has held up better than Chinese Buddhism because it has adapted itself better to the modern world and was not repressed like it and other religions were in Communist China. Because of Japan’s historical isolation and society, once Buddhism was introduced, it took on a definite Japanese character with sects developing like corporations so their survival would be ensured.

Buddhism is considered by some to be the most important religion in Japan. Introduced from China via and Korea around 552 A.D., Buddhism spread rapidly throughout Japan and has had a considerable influence on the nation's arts and social institutions. There are 13 schools (sects, shu) and 56 denominations, with the major one being Tendai, Shingon, Jodo, Zen, Soto, Obaku, and Nichiren. Japanese Buddhism is based on the Mahayana school, which emphasizes the attainment of Buddhahood. Temples and gardens of Japan, the famous Japanese tea ceremony (chanoyu), and the Japanese art of flower arranging (ikebana) owe their development to the influence of Buddhism.[Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Links in this Website: RELIGION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO SHRINES, PRIESTS, RITUALS AND CUSTOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST GODS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; ZEN AND OTHER BUDDHIST SECTS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EARLY BUDDHISM IN ASUKA-ERA JAPAN (A.D. 538 to 710) factsanddetails.com; PRINCE SHOTOKU factsanddetails.com; TODAIJI AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF BUDDHISM IN NARA-ERA JAPAN (A.D. 710-794) factsanddetails.com; NARA-ERA BUDDHIST MONKS, MANDALAS AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD BUDDHISM (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM AND CULTURE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) factsanddetails.com;

Buddhism in Japan Guide to Buddhism in Japan buddhanet.net ; Wikipedia article on Buddhism in Japan Wikipedia Buddhism and Shintoism in Japan A to Z Poto Dictionary onmarkproductions.com Honganji temple Site honganji.net ; History of Japanese Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Buddhism and Prince Shotoku onmarkproductions.com ; Asia Society article on Buddhism in Japan asiasociety.org Japanese-Buddhism.com japanese-buddhism.com; The Zen Site thezensite.com ; Wikipedia article on Zen Buddhism Wikipedia ; Photos Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Temples at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” (Wiley-Blackwell Guides to Buddhism) Amazon.com ;

“The Essence of Buddha: The Path to Enlightenment” by Ryuho Okawa Amazon.com ;

“Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death”

by Yoel Hoffmann Amazon.com ;

“Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com;

“Bonds of the Dead: Temples, Burial, and the Transformation of Contemporary Japanese Buddhism” by Mark Michael Rowe Amazon.com ;

“Three Japanese Buddhist Monks” (Penguin Great Ideas)

by Various and Meredith McKinney Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Zen Buddhism” by D. T. Suzuki, David Rintoul, et al. Amazon.com ;

Zen Buddhism: A History (Japan) (Volume 2) by Heinrich Dumoulin Amazon.com ;

“Saicho : The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School” by Paul Groner Amazon.com ;

“Kukai: Major Works”, Yoshito Hakeda (Translator) Amazon.com ;

“Shingon: Japanese Esoteric Buddhism” by Taiko Yamasaki, more Amazon.com ;

The Pure Land Handbook: A Mahayana Buddhist Approach to Death and Rebirth

by Master YongHua Amazon.com ;

“Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice”

by Charles B. Jones Amazon.com;

“The Three Pure Land Sutras: The Principle of Pure Land Buddhism”

by Jodo Shu Research Institute, Karen J. Mack, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Thus Taught Master Shichiri: One Hundred Gems of Shin Buddhist Wisdom”

by Rev. Gōjun Shichiri and Hisao Inagaki Amazon.com ;

“Nichiren: The Philosophy and Life of the Japanese Buddhist Prophet” (1916)

by Masaharu Anesak Amazon.com ;

“The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic”

by Gene Reeves Amazon.com ;

“Transform your energy - Change your life!: Nichiren Buddhism” by Susanne Matsudo-Kiliani, Yukio Matsudo Amazon.com ;

“The Five Eternal Guidelines of the Soka Gakkai”

by Daisaku Ikeda Amazon.com ;

“Encountering the Dharma: Daisaku Ikeda, Soka Gakkai, and the Globalization of Buddhist Humanism” by Richard Hughes Seager Amazon.com

Buddhists in Japan

As is the case with Shinto, estimates on the number of Buddhists in Japan varies greatly. According to one count there are 92 million of them, in another there are 37 million. The first figure reflects the majority of Japanese, who visit Buddhists temples and make offerings at Buddhist shrines from time to time, and attend Buddhist funerals. The second figure reflects more serious Buddhist followers. According to 2021 statistics on religion by the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, 135 million people in Japan were believers, Of these 47 million were Buddhists.

The are numerous Buddhist sects in Japan. The number of believers in each sect were approximately:

1) Jodo Buddhism (Jodo-shu, Jodo Shinshu, Yuzu Nembutsu and Ji-shu) — 22 million.

2) Nichiren Buddhism — 11 million

3) Shingon Buddhism — 5.5 million

4) Zen Buddhism (Rinzai, Soto and Obaku) — 5.3 million

5) Tendai Buddhism — 2.8 million.

Most Japanese Buddhist sects embrace beliefs of East Asian Mahayana ("Greater Vehicle") Buddhism, which preaches salvation in paradise for everyone rather than focusing on individual perfection as is the case with Theravada Buddhism favored in Southeast Asia.

Buddhism has traditionally been embraced by Japanese because it promised salvation and an afterlife. It is practiced in conjunction with Shinto beliefs — people often say prayers both to Buddha and Shintos kamis — and this is not considered contradictory. Today, Japanese Buddhism contains elements of Chinese-style ancestor worship. Most Japanese are "funeral Buddhists," meaning they partake in Buddhist rituals only when someone dies.

Some say Japan is secular society in line with that predicted for modernity by Max Weber, where Buddhism has become secondary to Japanese culture as a whole. Carl Bielefeldt wrote in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism: Surveys of the populace reveal that roughly 75 percent of Japanese identify themselves as Buddhist. These same surveys indicate that an even larger majority see themselves as Shinto, suggesting that, at least for many Japanese, being Buddhist does not mean an exclusive allegiance to that religion. Indeed, it is sometimes said that Japanese are born Shinto (i.e., receive blessings from a Shinto shrine at birth) and die Buddhist (receive Buddhist funeral and memorial services). [Source: Carl Bielefeldt, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004 =]

Vegetarianism has traditionally been associated with Buddhism. Many Japanese who consider themselves Buddhists are not vegetarians. However priests in sacred sites such as Koya-san are, Buddhist monks and nuns in Japan are recognizable by their shaven heads, distinctive robes, beads, and wooden sandals (geta). Pilgrims often carry a special staff or a wooden backpack for sutras, small statues, and other ritual paraphernalia. Usually, laypeople do not wear any special clothing unless they are on a religious pilgrimage or attending a funeral. =

Buddhist Beliefs

Buddhists believe that life is full of misery and hardship and that it is ultimately is unreal. The cycle of birth and rebirth continues because of attachment and desire to the "unreal self." Meditation and good deed will ultimately end the cycle and help the individual to achieve Nirvana, a state of blissful nothingness. To achieve this one must look inward and gain control of the mind and find internal peace. To achieve this takes time and is an evolutionary process that takes place in stages through many lifetimes and cycles or birth, death and rebirth to attain the "real soul" within a person which is in a constant state of flux. .

lotus flower Buddhists believe that only the things that matters is the inward self and outside world is not really real; that the goal of Buddhism is to reach a state of nothingness; and human beings are compositions of five temporary states — physical form, sensation, perception, volition and consciousness — all of which disappear after death. Buddhist deny the existence of an individual soul and tell their followers they must transcend this egocentric view to reach nirvana. In its purist forms, Buddhism has no beginning and no end, no Creation and no Heaven and no soul.

Buddhists believe: 1) life is full of suffering, death, sickness and the loss of loved ones; 2) life is perpetuated by reincarnation (rebirth); 3) suffering is caused by desire (particularly physical desire and the desire for personal fulfillment) and liberation from rebirth occurs with the elimination of desire; 4) eight steps ("The Eightfold Path") are necessary to live a good life on earth; 5) the only one way to escape suffering is the way of Buddha; 6) this path leads to nirvana; and 7) salvation comes with faith in Buddha and practice of Buddha law (Dharma) as preached by a community of monks (the Sangha).

There are many aspects of Buddhism that simply seem to be beyond expression. The religious historian I.B. Hunter described Buddhism as a religion of “affinities, depths, heights and subtleties, with its solidarity and cohesiveness, its clear pointing to something more than could be actually said in words.”

See Separate Articles BUDDHIST BELIEFS factsanddetails.com BUDDHA'S FIRST SERMON, THE MIDDLE WAY, FOUR NOBLE TRUTHS AND EIGHTFOLD PATH factsanddetails.com

Japanese Buddhist Beliefs

According to Japanese Buddhist cosmology the universe is composed of six realms with Mt. Sumisem — which stands 560,000 kilometers above the oceans that surround it — at the center. On the slopes are the realms of the “deva” (“tenbu” or “tenjo”), beings considered a rank below Bodhisattvas, with the Devas Benzai-ten and Daikoku-ten being particularly popular with ordinary people. Somewhere around the mountain is another realm, Ashura, the home of the deities where there is always some kind of fighting going on.

The other four realms are found on or under an island located near the edge of the universe. On the surface of the island is our world, the realm of the humans (“ningen”). Below it is the realm of nonhuman creatures, then a multiple-layered hell (“jogoku”) and finally the realm of the hungry ghosts (“gaki”), the saddest and most desperate place, where ghosts search endlessly for food and water the can not have for anything that enters their mouth turns to fire.

There is mobility between the realms. The occupants of any one realm are not thought of as residents but rather as visitors.

Mahayana Buddhism

Great Buddha of Nara Mahayana Buddhism encompasses a wide range of philosophical schools, metaphysical beliefs, and practical meditative disciplines. It that is more widespread and has more followers than Theravada Buddhism and includes Zen and Soka-gakkai Buddhism. It is practiced primarily in the northern half of the Buddhist world: in China, Tibet, Korea, Mongolia, Vietnam and Japan.

"Mahayana” means "the Great Vehicle.” The word vehicle is used because Buddhist doctrine is often compared to a raft or ship that carries one across the world of suffering to better worlds. Greater is reference to the universality of its doctrines and beliefs as opposed to narrowness of other schools. It rival sect Theravada Buddhism is referred in a somewhat dismissing way as the Hinayana (“Lesser Vehicle”) sect.

Mahayana Buddhism evolved around the A.D. 1st century during the second phase of Buddhist development as a reinterpretation of the Theravada rules for monks. It teaches that there is only one path to enlightenment and it is open to all beings; holds Bodhisattvas in great reverence; and places an emphasis on ritualistic practices, sutras and meditation and discourages forming attachments on the basis they are impermanent.

Mahayana spread to more distant lands than Theravada Buddhists because it allowed monks to travel more freely and was able to assimilate and accommodate local religions by using the concept of Bodhisattvas. Mahayana Buddhists have great reverence for Bodhisttavas, the future Buddha Maitreya and Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise and the Buddhist equivalent of a savior who helps followers get into "heaven.”.

See Separate Articles MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com MAHAYANA BUDDHIST BELIEFS: SIX COURSES, SKILLFUL MEANS, VOIDNESS AND HELL factsanddetails.com

Organization of Buddhism in Japan

A local Buddhist temple is supported by lay member, for whom it provides rituals and festivals, occasional pastoral care, and especially funerals and memorial services. These local institutions typically represent branch temples (matsuji) of the many denominations or schools (shū) into which Buddhism is divided. Religious corporations registered with the government are typically centered in a main temple (honzan). The main temple serves as symbolic and administrative headquarters.[Source: Carl Bielefeldt, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004 =]

modern Buddhist altar The larger denominations may include several monastic centers, parochial schools, and universities, and can claim thousands of local temples. The denominations of Buddhism, whether large or small, operate as independent religious entities. They have their own clergy, real property, distinctive scriptures, and rituals, as well as lay membership. There is no significant ecumenical body that governs the Buddhist community as a whole. Japanese Buddhism is the sum of its denominations. To be a Buddhist in Japan, one must be a member of one of these denominations.

For many centuries all Japanese were required by the government to be registered with a local Buddhist temple. Through this system Buddhist institutions were used by the government to maintain a census and the tax role. In exchange Buddhist temples had received government recognition and legal protection, as well as funding in some instances. This system was ended in the late nineteenth century.

Carl Bielefeldt wrote in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism, “The various Buddhist organizations are typically divided into two categories: denominations that trace their origins to ancient and medieval times, and the so-called new religions (shin shūkyo), founded in modern times. The former category is often understood as consisting of six sets of denominations, grouped on the basis of their historical association with particular traditional forms of Japanese Buddhism: 1) denominations based at temples in the ancient capital of Nara (e.g., the relatively small Hosso shū, Kegon shū, Risshū, and Shingon risshū); 2) denominations associated with the Tendai tradition; 3) denominations associated with the Shingon tradition; 4) denominations associated with the Pure Land form (e.g., the large Jodo shū, and still larger Honganji and Otani branches of the Jodo shinshū); 5) denominations associated with Zen (e.g., the large Soto shū, the small Obaku shū, and the various branches of the Rinzai shū); and 6) denominations associated with the tradition of Nichiren (e.g., the Nichiren shū and Nichiren shoshū). These groupings do not typically reflect institutional affiliations; contrary to common usage, there is no organization that could be called, for example, the Zen school or the Pure Land school. [Source: Carl Bielefeldt, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

New Religions in Japan and Buddhism

Carl Bielefeldt wrote in the Encyclopedia of Buddhism, “In the category of new religions, there is a wide variety of organizations, from small local groups, to large national, and even international, bodies such as the Soka Gakkai. A few date back to the mid-nineteenth century; most of the largest, such as Soka Gakkai, Reiyūkai, and Rissho kyoseikai, were founded during the first half of the twentieth century and flourished following World War II; still others arose in the last decades of the twentieth century, the most recent sometimes being referred to as the "new new religions" (shin shin shūkyo). Occasionally these organizations represent lay movements within a traditional denomination (such as Shinnyoen within a branch of Shingon or, until 1991, Soka Gakkai within Nichiren shoshū), but for the most part they are wholly independent bodies, typically founded and run by a lay leadership. [Source: Carl Bielefeldt, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

The older, more established organizations function much like the traditional denominations in providing services to a stable membership of lay households; the newer groups tend to be tailored somewhat more to the spiritual aspirations of individual converts. Some organizations base their teachings primarily on texts of the Buddhist canon, perhaps most often on the Lotus SŪtra (Saddharmapu arĪka-sŪtra); others have developed a distinctive scriptural corpus, which may combine traditional Buddhist material with elements drawn from other sources. Indeed, within the broad category of new religions are organizations, such as the notorious Aum shinrikyo, so eclectic in their beliefs and practices that it is difficult to identify them as Buddhist.

If the identification of some of the new religions as Buddhist may mask their more complex religious characters, the standard division of contemporary Buddhism into traditional denominations and new religions may also obscure as much as it reveals. The category of traditional denominations, for example, may suggest an orthodox, historically sanctioned heritage reaching back into premodern times, yet many of the contemporary forms of these denominations owe much to the same modern developments that produced the new religions. By the same token, the tendency, ascribed to the new religions, to incorporate into their Buddhism elements drawn from other sources, such as Shinto and popular religion, has an ancient history common to all the traditional denominations. Still, whether or not they can easily be applied to the contemporary scene, the two categories can be useful in revealing tensions, present throughout the history of Japanese Buddhism, between tradition and innovation, orthodoxy and heterodoxy, elite establishment and popular practice.

Japanese Buddhist Worship and Festivals

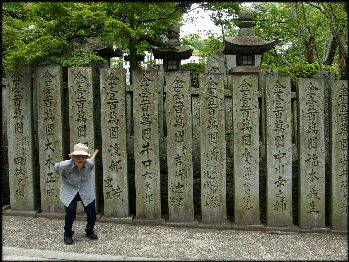

Japanese Buddhists worship statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas made of wood, bronze, and stone. These statues are believed to embody the deities. Statues of Buddhist prelates were also made and became objects of worship from the Kamakura period onwards. Mandalas are also sacred objects in Tendai and Shingon Buddhism. [Source: Gary Ebersole, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

One needs to take one's shoes off only if entering a temple. Hats should also be removed. Do not clap at Buddhist temples as you would at a Shinto shrine. Praying is done by prostrating oneself or bowing with hands clasped from a standing or seated position in front of an image of Buddha. Prayers are usually made after tossing a coin into the saisen-bako (offering box).

Taking the tonsure — shaving the hair of a monk — is the most important rite of passage for those becoming priests, monks or nuns. For most Japanese, the only rites of passage they engage in are the extended funerary and memorial rituals. Some Japanese Buddhists practice various forms of meditation, including Zen meditation and esoteric forms in Tendai and Shingon temples. Some followers, particularly those of Shugendo or mountain Buddhism, also engage in ascetic practices in the mountains, such as repeated ice water baths in the winter and fasting.

Japanese Buddhists celebrate the Buddha's birthday and enlightenment in early May. Specific schools also celebrate the anniversary of their founder's death (for example, Shingon Buddhists observe special rites for Kobo-daishi). The most important Buddhist festival is Bon, the festival of the dead, in mid-August. During this festival, the spirits of the deceased are invited back and entertained with song and dance before being sent off again. Each Buddhist temple has its own liturgical calendar. Additionally, some festivals, such as the Gion Festival in Kyoto, focus on syncretic Shinto-Buddhist deities.

See Separate Article: JAPANESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES factsanddetails.com

Buddhism, Death and Ancestor Worship in Japan

Buddhism, death and ancestor worship are linked together in Japan. Buddhist priests spend much of their time presiding over funerals. Buddhist temples contain family “butsudan”, or sacred boxes, where ancestral tablets (thought to contain the spirits of dead ancestors) and written prayers are placed. Some temples also contain hundreds of small jizo statutes for the souls of aborted children. You can often see parents making offerings of toys or small clothes to these statues.

After a death the family displays a picture of the deceased with black bunting in the home. Incense is burned and food offerings are made at this temporary shrine. Some widows leave a cup of tea on altar with a picture of their deceased husband every time they make tea. They often talk to the picture as if they are talking to a real person.

To pay respect to their deceased loved ones and ancestors Japanese leave offerings of red rice, sake and flowers and small markers that say "I WILL TAKE SHELTER IN THE LAND OF BUDDHA" at their graves. When pouring the sake over the grave they sometimes say things like "Oh, grandfather, you've had nothing to drink for so long. You must be very thirsty." Some Buddhist temples conduct ancient bon dances in which the souls of the dead are welcomed and then sent to a place of greater peace.

Ancestor worship involves the belief that the dead live on as spirits and that it is the responsibility of their family members and descendants to make sure that are well taken care of. If they are not they may come back and cause trouble to those family members and descendants. Unhappy dead ancestors are greatly feared and every effort is made to make sure they are comfortable in the afterlife. Accidents and illnesses are often attributed to deeds performed by the dead and cures are often attempts to placate them. In some societies, people go out of their way to be nice to one another, especially older people, out of fear of the nasty things they might do when they die.

Ancestor worship is still very much alive today. Ancestors are generally honored and appeased with daily and seasonal offerings and rituals. It has been said spirituality emanates from the family not a church or temple. Pictures of dead relatives are featured on family alters in many homes, where religious rituals and prayers are regularly performed.

See Separate Article: FUNERALS IN JAPAN: CREMATIONS, HIGH COSTS, BELIEFS ABOUT DEATH AND BUDDHIST CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

Cultural Impact of Buddhism on Japan

The impact of Buddhism on Japanese culture has been broad and extensive, influencing and even defining Japanese painting, calligraphy, sculpture, Japanese waka poems (31-syllable verses), kanshi (Chinese poems), prose, prose, poetry tales such as the Tale of Genji. Many Buddhist priests and nuns have been skilled and renowned poets, painters and calligraphers. [Source: Gary Ebersole,Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: “Buddhists introduced anthropomorphism (the representation of divinity in human form) to Japan. In medieval Japan the practice of many different art forms was undertaken as a form of religious discipline (michi or do). The way of tea, the way of poetry (kado), and the way of archery are only a few examples of this. In general, these forms of religio-aesthetic practice sought to focus the mind and to achieve a psychosomatic state in which action was egoless.

Buddhism influenced the forms of Japanese stage, including no, Kabuki, and the puppet theater, as well as the art of garden and landscape design, ranging from the earliest temple-shrine complexes, such as that in eighth-century Nara, to Zen gardens in the late medieval and early modern periods. Today Buddhist influence continues to be found in film, the theater, literature, painting, comics and anime, and other arts.

Decline of Buddhism in Japan

Donation markers While Buddhism is making a comeback in China, it is on the decline in Japan. "If it doesn't meet the changing needs of modern society, Japanese Buddhism will die," Yoshiharu Tomatsu, a Harvard-trained monk at the Jodo Shu Research Institute of Buddhism in Tokyo, told National Geographic. With the fast pace and competitiveness of Japanese society, young people in particular find little emotional support or sense of community in the ancient rituals of traditional Buddhism. "It's ironic," Tomatsu said, "As much as Japan has looked to the West for its cultural cues, it has not embraced the engaged Buddhism that has become so important among Buddhists in the West." [Source: Perry Garfinkel, National Geographic, December 2005]

The inability of Buddhism to address modern problem and to be relevant is regarded as one reason why so many people turn to cult religions in Japan. A monk at Mtizuzoin Temple in Tokyo told the Daily Yomiuri,”People have become estranged from places of worship, especially since the country’s period of rapid economic growth.”

Several decades ago, temples began offering rites of pacification for the spirits of aborted fetuses, known as mizuko kuyo. Abortion is not strong;y frowned upon in Japan, but the practice of mizuko kuyo has been criticized by some as a means for Buddhist priests to exploit vulnerable individuals for monetary gain.

Demographic trends have driven a decline in the number of danka, or parishioners who financially support a temple. Also, many young people these days tend to be indifferent toward religion. Under such circumstances, traditional Buddhist temples are looking for new ways to communicate with local residents.

Modernizing Buddhism in Japan — with Theater and Virtual Temples

In an attempt to attract younger followers Buddhist temples are hosting concerts and noh performances, staging musicals and magic shows and encouraging monks to perform stand-up comedy routines and do little dances when they chant Buddhist sutras. A monk at the Kansho Tagai temple in Tokyo told the Daily Yomiuri, “A temple’s Hondo [main building] is meant to be a place where people get together and mingle. But people are forgetting this.” At his temple a number of events are staged which have allowed people to get together and have a good time and get to know each other.

In Japan there is dial-a-monk service. Typically callers are worried about high funeral costs and want advice on how to save money. In June 2009, the Koysan Shingon Buddhist sect said it was going to help monks and priests and single women affiliated with its temples to find spouses as part of an effort tp make sure the sect stays alive as it is having an increasingly hard time finding priest to manage its temples.

Temple charms Many Buddhist temples are turning to non-traditional practices to earn money and keep going. For example, Shokoji Temple — a Zen Buddhist temple in Kawachinagano, Osaka Prefecture — offers lay person seminars to help young people find jobs. Monks of the Jodo Shinshu and Sotoshu sects jointly opened a virtual temple called Higanji (www.higan.net) featuring event information, blogs by monks and recipes for shojin ryori vegetarian dishes. The site has as many as 10,000 hits a day. "Furii-sutairu na Soryo-tachi" (Monks who use unconventional methods), a group comprising young monks in the Kansai region, issues free papers carrying information related to Buddhism. The group holds discussions with readers every month. [Source: Masanori Genko, Yomiuri Shimbun, January 8, 2011]

Ryuho Ikeguchi, 30, a Jodoshu monk, told the Yomiuri Shimbun: "Many people say that in today's society, an increasing number of people lack social bonds and are neglected. But we've received requests to help make temples the centers of local communities. "As various people come together and 'weave' relationships with them, the threshold between temples and local residents will become lower, and it may eventually make it possible to rebuild a community in which Buddhism plays a pivotal role."

Otenin temple — known as the "theater temple" — is a drum-shaped concrete subtemple of Dairenji temple in Osaka, not far from the Namba entertainment district. Built in 1997, it is equipped with sound and lighting equipment and is open to the public as a theater with an audience capacity of 140. Performances are held almost every week. About 30,000 people, mainly young people, use the hall annually. Otenin does not have danka. Instead, a nonprofit organization of local residents manages events to be held in the temple, including lectures on themes such as education and welfare, with the aim of becoming a hub of the community. "Just as temples used to do in the old days, our temple is preaching and spreading knowledge to people in the community, but not only to particular ones [danka] but people in general," Mitsuhiko Akita told the Yomiuri Shimbun.

Activist Buddhism in Japan Today

Perry Garfinkel wrote in National Geographic: Among “the signs that the heart of Japanese Buddhism is at least still beating” is “is an organization...established in 1993. Called Ayus, meaning "life," it channels about $300,000 a year to national and international groups working for peace and human rights. Two-thirds of the 300 contributing members are Buddhist priests. There's also the sect called Rissho Kosei-kai, founded in 1938 and now boasting 1.8 million households. While firmly planted in the Buddha's teachings, this organization is different. It's a lay group — and it emphasizes service to others. Members forgo two meals a month, donating the money to the sect's peace fund. Rissho Kosei-kai has given about 60 million dollars to UNICEF in the past 25 years. [Source: Perry Garfinkel, National Geographic, December 2005]

At the sect's world headquarters in Tokyo, the imposing central meditation hall has a ceiling-high pipe organ and stained-glass windows — more like a Christian church than a Buddhist temple. Tomatsu and I sit in on a hoza, or dharma session, focusing on the social problems that beset Japan but remain conversational taboos: divorce, drug addiction, depression, suicide. In a large, brightly lit multipurpose room, casually dressed participants, mostly women, sit in metal folding chairs in a loose circle around a facilitator, sharing personal dilemmas such as marital problems, disrespectful kids, and aging parents. After each story, the group issues a supportive round of applause. It's a reminder that the new Buddhism doesn't always have to address global issues; the kitchen table can be a war zone too.

Tomatsu also introduces me to Rev. Takeda Takao, a Buddhist priest whom I'd seen leading a protest in front of Japan's parliament building in the heart of Tokyo. Hundreds of demonstrators had gathered to oppose the national Self Defense Forces' involvement in Iraq. Amid the chaos, Takao, in a monk's vest, stood at curbside with several other priests carrying bullhorns, drums, and a banner.

The great bell at Chion Temple in Kyoto in the 19th century

Takao belongs to Nipponzan Myohoji, an international Buddhist organization founded in 1918 whose monks and nuns conduct long peace marches, chanting and beating their drums all the way. "Peaceful protest is the only way to make a peaceful planet," he says. It's a conclusion he came to after participating in demonstrations against the construction of Tokyo's Narita Airport. In the 1970s several policemen and protesters were killed, and thousands injured, defending the rights of vegetable farmers whose land had been taken by the government for the runway. As a monument to the tragedy, the Nipponzan Myohoji Order erected a peace pagoda in 2001 just outside the airport fences.

Image Sources: 1) Nara Buddha, guardian deity, lotus, temple charms, Ray Kinnane 2) Shotaku images, Onmark productions, 3) golden Buddha, altar, Association for the Promotion of Traditional Crafts Industries in Japan 4) Kamakura Buddha, Visualizing Culture, MIT Education

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024