PRINCE SHOTOKU

Prince Shotoku

The most important Asuka ruler was Shotoku Taishi (born in 574, ruled 593-622). Regarded as the "father of Japanese Buddhism," he made Buddhism the state religion by constructing major Buddhist temples such as Horyu-ji near Nara. His was goal was to create a harmonious society. Recognized as a great intellectual in period of reform, Shotoku was a devout Buddhist but was also well read in Chinese literature and influenced by Chinese philisophy and political thought.

Shotoku Taishi (Prince Shotoku) is one of the best-know figures of Japanese history. Sometimes called the founder of the Japanese nation, he has appeared on Japanese banknotes more than any other person — three times before World War II and four times after for a total of seven times. The term “shotoku-taishi” was once a slang for money. The name “shotoku” is made from the Chinese characters “sho” and “toku” which means “sacred” and “virtue” respectively.

Prince Shotoku (573-621) was the nephew of Empress Suiko and served as regent and trusted advisor on matters of civil administration during her reign. He is recorded in the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters, 712) and the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720) as having been a great Buddhist scholar and statesman who lived in early Japan (574-622). He dispatched an official diplomatic delegation to China, established the Seventeen Article Constitution in A.D. 592 and brought together the priest-chiefs of the major clans into a somewhat centralized government based on the Chinese model. He began asserting Japan’s power, and once wrote a letter to the Emperor of China, addressing to "from the Emperor of the Rising Sun to the Emperor of the Setting Sun."

A famous 8th century hanging scroll painting n the collection of Horyuji Temple shows Prince Shotoku as a bureaucrat dressed in Chinese-style court clothes in official headgear and aristocratic shoes, holding a wooden paddle-like object that is a crib sheet required for court rituals. He is shown carrying a jeweled sword, the imperial symbol of political and military authority. Another surviving depiction dates to later times, shows Shotoku the scholar and dedicated sponsor of Buddhism. He is depicted wearing ceremonial court dress and lecturing on the sacred texts, the sutras. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

Websites: Yamato Period Wikipedia article on the Yamato period Wikipedia article ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindexList of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Buddhism and Prince Shotoku onmarkproductions.com ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org . References: 1) The Chronicles of Wa, Gishiwajinden by Wes Injerd; 2) Wa (Japan), Wikipedia; 3) Excerpts from the History of the Kingdom of Wei, Columbia University’s Primary Source Document Asia for Educators. Asuka Wikipedia article on Asuka Wikipedia ; Asuka Park asuka-park.go.jp ; Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage sites ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Essay on Early Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ASUKA PERIOD (A.D. 538 TO 710) factsanddetails.com; EARLY BUDDHISM AND POLITICAL STRUGGLES IN ASUKA-ERA JAPAN factsanddetails.com; TAIKA REFORMS AND EMPERORS TENJI AND TENMU factsanddetails.com; ASUKA GOVERNMENT AND ECONOMY AND THE RITSURYO SYSTEM factsanddetails.com; ASUKA, FUJIWARA AND ASUKA-ERA CITIES AND TOMBS factsanddetails.com; CULTURE AND LITERATURE FROM THE ASUKA PERIOD (A.D. 538 TO 710) factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ARCHITECTURE: PALACES AND BUDDHIST TEMPLES factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ART factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan” (2008) by Donald F. McCallum Amazon.com; “A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” by William E. Deal, Brian Rupper Amazon.com; “Plotting the Prince: Shotoku Cults and the Mapping of Medieval Japanese Buddhism” by Kevin Gray Carr Amazon.com; “Nihongi: Volume I - Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697" by W G Aston Amazon.com; “The Kojiki: An Account of Ancient Matters” by no Yasumaro Ō and Gustav Heldt Amazon.com; “Man'yoshu” by Alexander Vovin Amazon.com; “Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan” by William Wayne Farris Amazon.com;“The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Koji Mizoguchi Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Companion to Japanese Archaeology (Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology)” by Werner Steinhaus, Simon Kaner, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan” by Gina L. Barnes Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan” (Volume 1) by Delmer M. Brown Amazon.com

Prince Shotoku and Buddhism

Peter A. Pardue wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, “Shotoku assumed the regency at a time when there was growing strife between the leading clans over imperial succession. He converted to Buddhism as a layman and, with the assistance of Korean monks, began to reconstruct his society on the broader ethical and cultural base provided by the new values. [Source: Peter A. Pardue, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

Shotoku looking like Buddha

The innovatory significance of this conversion is suggested by a passage in one of the sutra commentaries attributed to him: “The world is false — only the Buddha is true” In this ecstatic affirmation of the fundamental principle of world rejection, he appears to have taken the first step in the process of liberating his society from the burden of the archaic institutions which surrounded him. His reconstructive enterprise was spelled out in a new ideology, embodied in a 17-article constitution — a fusion of Buddhist universalism and Confucian ethics.

Shotoku actually ruled from the monastery, availing himself of its legitimation and the leverage provided by the monastic order. He sent embassies to China to bring back knowledge of Chinese civilization, which became the basis for the later Taika reform and codes based on Tang law, land systems, and bureaucratic principles.

Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: “Prince Shotoku is often compared to Buddha, as a prince who renounced secular power to devote himself to religious studies, or seen as a pacifist who sought to unify his country through Buddhist doctrine in turbulent times. The earliest sources indicate that the promotion of Shotoku worship was initiated by the imperial family, particularly through two significant historical books, the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters, 712) and the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720), and was sanctioned by imperial command. Through the prevalent Shinto mythology linking the imperial descent from the goddess Amaterasu and by elevating the Prince Shotoku as charismatic sage, benevolent and humanistic patron, ideal regent, and giving him kami status, the imperial court successfully promoted Shotoku as imperial ancestor and national hero.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

Buddhism in Japan Under Prince Shotoku

Prince Shotoku was a serious Buddhist practitioner who sought to create a centralized political system based on the Chinese model. To him, Buddhism was the epitome of a great civilization. The early Japanese turned to Buddhism for worldly benefits, including good health, longevity, prosperity, and protection from lightning, fire, and pestilence. Buddhism flourished under government sponsorship and the patronage of the powerful Soga family in Nara, the first permanent capital, founded in 710. In time, large temples established far-flung networks of affiliated temples and shrines and came to control vast estates.[Source: Gary Ebersole, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Under Shotoku Buddhism became the state religion, scriptures, art and craftsmen were brought in from Korea and Japanese monks were sent abroad to study. Temples were founded, monks were ordained and ceremonies were held publicly. Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: Prince Shotoku is renowned for his patronage of Buddhist temples that brought about a flowering of Buddhist arts and culture. When Empress Suiko declared her acceptance of Buddhism in 593, in the same year, Prince Shotoku ordered the construction of Shitennoji Temple (in present-day Osaka) . Thought of as a dedicated Buddhist scholar who composed commentaries on the Lotus Sutra, the Vimalakirti Sutra, and the Sutra of Queen Srimala, he is also credited with having founded the Horyuji Temple in the Yamato province. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

“In 605, Prince Shotoku took up residence in Ikaruga and shortly after built Ikarugadera Temple. Documentation at Horyuji temple substantiate Prince Shotoku along with Empress Suiko as founders of the temple during the year 607. Archaeological excavations have confirmed the existence of Prince Shotoku’s palace, the Ikaruga-no-miya in the eastern part of the current temple complex.

Prince Shotoku and Confucianism

Shotoku as a Confucian

Shotoku was influenced by Confucian principles, including the Mandate of Heaven, which suggested that the sovereign ruled at the will of a supreme force. Under Shotoku’s direction, Confucian models of rank and etiquette were adopted, and his Seventeen Article Constitution (Kenpo jushichiju) prescribed ways to bring harmony to a society chaotic in Confucian terms. In addition, Shotoku adopted the Chinese calendar, developed a system of highways, built numerous Buddhist temples, had court chronicles compiled, sent students to China to study Buddhism and Confucianism, and established formal diplomatic relations with China. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Prince Shotoku was the first Japanese person to understand Buddhism, saying, “the world is false, Buddha alone is true”. This was the first concept of world negation in Japan. Prince Shotoku issued a document known as 17-Article of the Constitution. “Its moral precepts are largely Confucian, somewhat influenced by ideas of the Legalists [those who opposed Confucianism in the time of the burning of the books], a school of thought in China which held that social order depended not on Confucian ethical precepts but on the development and application of a body of law.” [Source: “Kagami, Susanoo no mikoto and Confucianism” pperov.angelfire.com ==]

“But for his ultimate source of legitimacy, Shotoku turned to Buddhist teachings. Confucianism (Rújia) was developed from the teachings of Confucius (Kong Fuzi, or K’ung-fu-tzu, lit. “Master Kong”, 551–479 B.C.) Japan was influenced by Confucianism in a different way than China, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam and Singapore. Confucianism stresses the importance of education for moral development of the individual so that the state can be governed by moral virtue rather than by the use of coercive laws. Lead the people with administrative injunctions and put them in their place with penal law, and they will avoid punishments but will be without a sense of shame. Lead them with excellence and put them in their place through roles and ritual practices, and in addition to developing a sense of shame, they will order themselves harmoniously.” ==

Seventeen-Article Constitution of Prince Shotoku

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Beginning in the late 6th century, Japan’s Yamato rulers sought to refashion themselves from clan chieftains into fully fledged monarchs on the Chinese model. One of the first landmarks in the effort to remake the Japanese state in the form of China’s sophisticated political institutions was the Constitution of Prince Shotoku, also known as the “Seventeen-Article Constitution.” [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Shotoku lecturing

The “Seventeen-Article Constitution of Prince Shotoku” reads: “A.D. 604, Summer, 4th Month, 3rd day. The Prince Imperial Shotoku in person prepared laws for the first time. There were seventeen clauses, as follows: 1) Harmony should be valued and quarrels should be avoided. Everyone has his biases, and few men are far.sighted. Therefore some disobey their lords and fathers and keep up feuds with their neighbors. But when the superiors are in harmony with each other and the inferiors are friendly, then affairs are discussed quietly and the right view of matters prevails. [Source: adapted for modern readers from W. G. Aston’s “Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697,” in “The Transactions and Proceedings of the Japan Society of London”, Supplement 1, vol. 2 (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co., Ltd., 1896), 128-33. The text is reproduced here as it appears in “Japan: Selected Readings”, compiled by Hyman Kublin (Houghton Mifflin Company), 31-34; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

2) The three treasures, which are Buddha, the (Buddhist) Law and the (Buddhist) Priesthood; should be given sincere reverence, for they are the final refuge of all living things. Few men are so bad that they cannot be taught their truth.

3) Do not fail to obey the commands of your Sovereign. He is like Heaven, which is above the Earth, and the vassal is like the Earth, which bears up Heaven. When Heaven and Earth are properly in place, the four seasons follow their course and all is well in Nature. But if the Earth attempts to take the place of Heaven, Heaven would simply fall in ruin. That is why the vassal listens when the lord speaks, and the inferior obeys when the superior acts. Consequently when you receive the commands of your Sovereign, do not fail to carry them out or ruin will be the natural result.

4) The Ministers and officials of the state should make proper behavior their first principle, for if the superiors do not behave properly, the inferiors are disorderly; if inferiors behave improperly, offenses will naturally result. Therefore when lord and vassal behave with propriety, the distinctions of rank are not confused: when the people behave properly the Government will be in good order.

5) Deal impartially with the legal complaints which are submitted to you. If the man who is to decide suits at law makes gain his motive, and hears cases with a view to receiving bribes, then the suits of the rich man will be like a stone flung into water, meeting no resistance, while the complaints of the poor will be like water thrown upon a stone. In these circumstances the poor man will not know where to go, nor will he behave as he should.

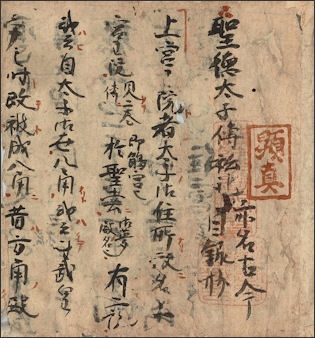

Shotoko Taishi den shiki

6) Punish the evil and reward the good. This was the excellent rule of antiquity. Therefore do not hide the good qualities of others or fail to correct what is wrong when you see it. Flatterers and deceivers are a sharp weapon for the overthrow of the state, and a sharp sword for the destruction of the people. Men of this kind are never loyal to their lord, or to the people. All this is a source of serious civil disturbances.

7) Every man has his own work. Do not let the spheres of duty be confused. When wise men are entrusted with office, the sound of praise arises. If corrupt men hold office, disasters and tumult multiply. In all things, whether great or small, find the right man and they will be well managed. Therefore the wise sovereigns of antiquity sought the man to fill the office, and not the office to suit the man. If this is done the state will be lasting and the realm will be free from danger.

8) Ministers and officials should attend the Court early in the morning and retire late, for the whole day is hardly enough for the accomplishment of state business. If one is late in attending Court, emergencies cannot be met; if officials retire early, the work cannot be completed.

9) Good faith is the foundation of right. In everything let there be good faith, for if the lord and the vassal keep faith with one another, what cannot be accomplished? If the lord and the vassal do not keep faith with each other, everything will end in failure.

10) Let us control ourselves and not be resentful when others disagree with us, for all men have hearts and each heart has its own leanings. The right of others is our wrong, and our right is their wrong. We are not unquestionably sages, nor are they unquestionably fools. Both of us are simply ordinary men. How can anyone lay down a rule by which to distinguish right from wrong? For we are all wise sometimes and foolish at others. Therefore, though others give way to anger, let us on the contrary dread our own faults, and though we may think we alone are in the right, let us follow the majority and act like them.

11) Know the difference between merit and demerit, and deal out to each its reward and punishment. In these days, reward does not always follow merit, or punishment follow crime. You high officials who have charge of public affairs, make it your business to give clear rewards and punishments.

12) Do not let the local nobility levy taxes on the people. There cannot be two lords in a country; the people cannot have two masters. The sovereign is the sole master of the people of the whole realm, and the officials that he appoints are all his subjects. How can they presume to levy taxes on the people?

13) All people entrusted with office should attend equally to their duties. Their work may sometimes be interrupted due to illness or their being sent on missions. But whenever they are able to attend to business they should do so as if they knew what it was about and not obstruct public affairs on the grounds they are not personally familiar with them.

14) Do not be envious! For if we envy others, then they in turn will envy us. The evils of envy know no limit. If others surpass us in intelligence, we are not pleased; if they are more able, we are envious. But if we do not find wise men and sages, how shall the realm be governed?

15) To subordinate private interests to the public good — that is the path of a vassal. Now if a man is influenced by private motives, he will be resentful, and if he is influenced by resentment he will fail to act harmoniously with others. If he fails to act harmoniously with others, the public interest will suffer. Resentment interferes with order and is subversive of law.

16) Employ the people in forced labor at seasonable times. This is an ancient and excellent rule. Employ them in the winter months when they are at leisure, but not from Spring to Autumn, when they are busy with agriculture or with the mulberry trees (the leaves of which are fed to silkworms). For if they do not attend to agriculture, what will there be to eat? If they do not attend to the mulberry trees, what will there be for clothing?

17) Decisions on important matters should not be made by one person alone. They should be discussed with many people. Small matters are of less consequence and it is unnecessary to consult a number of people. It is only in the case of important affairs, when there is a suspicion that they may miscarry, that one should consult with others, so as to arrive at the right conclusion.

Shotoku directing the attack on Moriya's castle

Prince Shotoku’s Rule

Prince Shotoku established a court system with twelve grades of court rank based on merit and achievement and drew up the first Japanese constitution in Chinese around 604. Kawagoe wrote: A closer examination of the Seventeen-Article Constitution (Jushichjjo kenpo) shows that Shotoku used the constitution as a vehicle to strengthen the notion of the absolute authority of the emperor as well as to promote Buddhism as the official religion. The constitution was both a moral code and a code of personal and social behaviour. Its basic tenet was harmony: “Harmony is the most precious asset. We all alternate between wisdom and madness. It is a closed circle.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

“Acting as regent for Empress Suiko, Prince Shotoku instituted important reforms that laid the ideological foundations for a Chinese-style centralized state under the authority of the emperor. In Article II, Shotoku’s injunction to rely on the Three Treasures was especially significant because it officially promoted Buddhism in Japan and honored Shotoku as the father of Japanese Buddhism.

“The constitution thus entrenched both Confucian-ideals and Buddhism as a state religion, having the powerful effect of cementing the relationship between the emperor, the nobility and the clergy. Hence, Prince Shotoku and his constitution are today seen as a unifying force in Japanese society. Later in medieval Japan, the Seventeen-Article Constitution that Shotoku promulgated was to become an important source among ruling authorities, the shogun, court, aristocracy, and temple establishments who promoted Shotoku worship, for bolstering their claims to authority. “

Prince Shotoko’s Caps and Court Rank System

Kawagoe wrote:” In 604, along with the promulgation of the Seventeen Article Constitution, Prince Shotoku established the court ranks, kan’i junikai or the twelve grades of cap rank (or twelve grades of colored coronets). Under this system, the imperial court relied on experienced and skilled officials who were appointed and promoted on the basis of their ability to perform specialized administrative tasks. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

“The ministers, officials of the highest status under the system, were given caps of purple silk decorated with gold and silver indicating their assigned court rank. The silk was colored by purple dyes from the “murasakigusa” (Lithosperumum erythorhizon siebetzucc) a plant which is today a protected species. Murasaki or purple has since ancient times been a color that symbolized authority, nobility and splendor. Below these ministers, the other officials of twelve grades wore caps of different colors, other than purple.

Shotoku quelling Mononobe no Moriya

“One high managerial official post emerged; that of the imperial secretary (maetsukimi/taifu) who presided at important court events, the reception of foreign missions and imperial conferences attended by high-ranking ministers. The imperial secretary reported directly to the throne. At lower levels, other officials bearing the cap and ranks were chosen for their ability to perform specialized functions: the use of imported techniques for producing weapons and tools, building palaces and temples, making statues, bells, paintings and other symbolic and ecorative works of art. These newly created ranks and positions were a significant immigration policy that made provision for immigrants with expertise and achievement — as opposed to a rank by birth in a historically prominent local clan.

“This cap-and-court rank system that hailed originally from China, was not identical to those in place in the Paekche and Koguryo Korean kingdoms, and so is thought to have been a modified creation of Prince Shotoku. For the time being, the old hereditary clan title uji-kabane system remained in place but the kan’i junikai system set in motion the first step towards the replacing of the old uji-kabane order.”

Prince Shotoku and China

Numerous official missions of envoys, priests, and students were sent to China in the seventh century. Some remained twenty years or more; many of those who returned became prominent reformers. In a move greatly resented by the Chinese, Shotoku sought equality with the Chinese emperor by sending official correspondence addressed "From the Son of Heaven in the Land of the Rising Sun to the Son of Heaven of the Land of the Setting Sun." Shotoku’s bold step set a precedent: Japan never again accepted a subordinate status in its relations with China. Although the missions continued the transformation of Japan through Chinese influences, the Korean influence on Japan declined despite the close connections that had existed during the early Kofun period. [Source: Library of Congress]

Kawagoe wrote: “Prince Shotoku is credited for opening relations with China by sending a mission to the Sui emperor. Some of his foreign policy actions were regarded as less than successful such as his failure to restore control of Mimana, reportedly a tributary kingdom of Japan in Korea.Prince Shotoku also despatched envoys of Korean descent who could read Chinese in 607 to China. Ancient records tell us that the boat coasted the Korean shoreline as a direct passage was too dangerous. Also the chief envoy had asked the Chinese emperor to address Japan as “Land of the Rising Sun” instead of “Land of Dwarfs” which was perceived as a derogatory term by Japan. But according to Chinese Sui records, the Sui emperor did not receive well the communication which was addressed “from the emperor of the sunrise country to the emperor of the sunset country”. The Japanese request was not acceded to, until 670 when the same request had to be repeated…even though four Japanese missions were sent to China during the brief duration of the Sui dynasty.” [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

Legendary Prince Shotoku: Fact Versus Fiction

Shotoku hidden on a tree

Many details of Prince Shotoku’s life are recorded in Nihon Shoki, (Japanese Chronicles), a document compiled in 720. According to the document Shotoku stood up and began praying soon after he was born and could understand 10 people talking to him at the same time. The document lists a variety of noble deeds performed by the prince. When he died everyone from court members to farmers to children wept. The Nihin Shoki states all of Prince Shotoku’s descendants died at Horyuji temple in 643 after being cornered there by Soga bo Iruka, a powerful politician at the time. It is not stated whether they were killed or committed suicide. Some scholars believe that Horyji Temple was rebuilt by Shotoku’s enemies to appease the ghosts of his revenged-inclined descendants.

Kawagoe wrote: Like most legendary figures of old, it is impossible to separate from fact some accounts of Prince Shotoku’s life. By most accounts he was a remarkable man who did remarkable things and many benevolent works for the nation. Some accounts are harder to swallow. According to legend, his birth, like that of Buddha, was a miraculous birth: born without pain, that he was a precocious child who spoke from the moment of his birth. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

“Shotoku served as an ideal figure, particularly because not only did he represent the imperial family through his regency, but he was also regarded as the father of Japanese Buddhism in his role as progenitor of Buddhism in Japan. Prince Shotoku was thus a unique historical character who had gained his giant status as a result of his significant contributions in two fields: as a statesman to the Japanese nationhood and to Japanese Buddhism. However, Shotoku’s status went beyond that of a historical figure; by virtue of his charisma and popular influence he rose to the level of kami. Soon after his death, Prince Shotoku, post-humously, gained great legendary status. That legendary status probably began with his deification at temple complexes closely associated with him and which was further promoted by the close and interdependent ties between the state and Buddhism at the time. Interestingly, hardly any early accounts of Buddhist sources on Shotoku worship exist because the imperial authorities either served in the dual capacity as religious authorities, or because they used Buddhism as a tool to support the interests of the state.

Tanzan jinja

“There remain sceptics (e.g. Chubu University professor Oyama Seiichi’s Prince Shotoku, Tokyo Shimbun 2008-02-10 refers) who assert that Prince Shotoku was not a real historical person. Nevertheless, there were many factual details of Prince Shotoku’s life that cannot be easily ignored, such as the excavated ruins of his residential palace at Ikaruga...Chinese records of the Sui period substantiate Prince Shotoku’s role in diplomacy that is detailed in the Nihon shoki... A tantalizing detail is the portrait of Prince Shotoku that survives till today in the form of the gilt bronze statue (called the Yumedono Kannon or Dream Hall Kuanyin) that was ordered to be made “in the image of Prince Shotoku” in the year of 621 of Shotoku’s death. The face on the statue features a broad nose, prominent lips and narrow eyes and the figure possesses large hands.

“The Yumedono Kannon statue was originally placed in the Hall of Dreams of the original Horyuji Temple that had burned down in 672. The statue survived the fire and can be viewed once a year at the existing Horyuji Temple’s Hall of Dreams built in 739 as the memorial building that replaced the earlier one. Another statue in the Horyuji Temple is the Shaka triad, an inscription on the Shaka triad states that the statue was created as a life-size replica of Prince Shotoku himself. It was made at the time of his death as a prayer for his ascent into the Pure Land. Mention is also made of the death of Prince Shotoku’s mother and his principle wife (who are thought to be two attendants in the Shaka triad).”

Legend of Shotoku Taishi and the Starving Beggar

The Nihon shoki describes an episode of Shotoku’s sympathetically reaching out to a starving man: Suiko 21 (613) 12th month,1st day. Prince Shotoku traveled to Kataoka. At that time,a starving man was lying by the side of the road. Accordingly,the crown prince asked him his name,but the man did not respond. Shotoku, observing this situation, provided the man with food and water and removed the coat he was wearing and covered the starving man with it. He said to him,“Lie there in peace.”

Shotoku and the gourd

Shotoku then sang this verse:

On the sunny hill of Mount Kataoki,

Look! There lies a poor traveler

Starving for food.

Were you born without parents?

Without a lord prosperous as a bamboo?

Look! There lies a poor traveler

Starving for food.

— The Prince and the Monk: Shotoku Worship in Shinran Worship, K.D.Y. Lee

The dying beggar tale gets developed with more embellishments with later version over time. In a popular version of the story the starving man turns out to be none other than Daruma Taishi (Bodhidharma), an important figure in Japanese Buddhism. For more readings on the legend see: A Waka Anthology: Volume One: The Gem-Glistening Cup p. 113-114; The Prince and the Monk: Shotoku Worship in Shinran’s Buddhism by Kenneth Doo Lee. Page 54 the embellishments to the dying beggar tale and the development of the legendary sage and kami status of Shotoku Taishi [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

Darumaji Temple, Shotoku Taishi and the Starving Beggar

Darumaji Temple

Darumaji is a temple belonging to the Nanzenji branch of Rinzai Zen tradition of Buddhism in Nara. The temple appears in the Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) entry for December of the 21st year of the reign of Emperor Suiko (613). The temple maintains that it was founded at the place Prince Shotoku met the starving man near Mt. Kataoka. The temple contains a crystal quartz reliquary in the shape of a Five Elements Stupa and the stone Hokyoin pagoda excavated from what is said to be the starving man’s grave) below the main hall. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

During repairs to the main hall, a small stone chamber was detected with a stone stupa deposited in upright position. A square hole had been carved into the body of the stupa, in which a haji ware lidded vessel had been placed, within which a quartz crystal reliquary in the shape of a Five Elements Stupa was found, in which a relic had been placed.

According to the report of the excavations of Darumaji: A stone stupa, ordinarily erected above ground, being deposited in an underground stone chamber in upright fashion, is exceedingly rare. From a typological examination of the artifacts, including the stone stupa, and the results of investigations in the vicinity of the main hall, the deposit is inferred to have been made around the mid 13th century. As the grave (kofun) of the starving man, held to have been an incarnation of Bodhidharma, was repaired at about the same time that Darumaji was founded, it is thought that the stone stupa was deposited in connection with the repair of the tomb. These artifacts and features may be evaluated as showing a new facet of Buddhist relic belief that was popular nationwide in the Medieval period. [Source: “Extract from: Darumaji: A stone stupa deposited upright, a new facet of Medieval Buddhist relic belief” by Okajima Eisho, Yamada Takafumi (http://archaeology.jp)]

Prince Shotoku Worship

Prince Shotoku Kawagoe wrote: In early Japan, Prince Shotoku was portrayed mainly as the regent prince with imperial lineage traceable to sun goddess Amaterasu, kami and a deified bodhisattva. During the medieval period however, Shotoku worship became a widespread and popular trend. By then Prince Shotuku had evolved a new status as a Buddhist deity, and was worshipped as such during the medieval period that was a time when Buddhist temples’ ties with the imperial court were weakening. As Buddhist institutions began to assert their independence from the imperial court, they began to promote Shotoku in different ways, according to their own interpretations and elevation of Shotoku primarily as a Buddhist saint or deity. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

“A key element that helped to effectively fallowed the smooth promotion of Shotoku worship as a Buddhist figure was through the honji sujaku context of the medieval period. Shotoku worship evolved further through the legends that now portrayed Shotoku not only as a powerful kami, but also as a reincarnation of Tendai Eshi, as a manifestation of bodhisattva Kannon, and later, as Amida Buddha and even Shinran himself (Shinran was a monk who spent twenty years of religious training at Mount Hiei after which he apprenticed under his master Honen, who took Shinran on as his apprentice to learn the senju nenbutsu teaching).

“Like most people in medieval Japan, Shinran revered Shotoku Taishi as a cultural and religious icon, but his worship of Shotoku went beyond the religious and political role of Shotoku – he worshiped Shotoku as his personal savior, which is evident from his devotional hymns in praise of Shotoku. Shinran’s described Shotoku as ‘Guze Kannon’ or ‘the world-saving bodhisattva of compassion’ of Japan. For Shinran, Shotoku was more than a historical and legendary figure—Shotoku was his personal savior. Shinran became the first Buddhist monk who rejected his clerical vows of celibacy, openly married and had children with Eshinni. His wife’s account of Shinran’s dream reveals his rationale for marrying Eshinni and his profound worship for Shotoku: In his dream, Shotoku, who appeared to Shinran as a manifestation of Kannon, assured Shinran that “she” would incarnate herself as Eshinni, thereby permitting Shinran to marry Eshinni with the implication that he would actually be marrying Kannon.”

After Prince Shotoku

The Nihin Shoki states all of Prince Shotoku’s descendants died at Horyuji temple in 643 after being cornered there by Soga bo Iruka, a powerful politician at the time. It is not stated whether they were killed or committed suicide. Some scholars believe that Horyji Temple was rebuilt by Shotoku’s enemies to appease the ghosts of his revenged-inclined descendants.

About twenty years after the deaths of Shotoku (in A.D. 622), Soga Umako (in A.D. 626), and Empress Suiko (in A.D. 628), court intrigues over succession and the threat of a Chinese invasion led to a palace coup against the Soga oppression in A.D. 645. The revolt was led by Prince Naka and Nakatomi Kamatari, who seized control of the court from the Soga family and introduced the Taika Reform.

Kawagoe wrote:After the death of Soga no Emishi in 645, the rulers and administrators in Asuka adopted reforms that led to the formation of a Chinese-style state known as the ritsuryo state. Measures were taken to increase the emperor’s autocratic power by making Buddhism a state religion. Buddhist temples and Buddhist worship were used in support of the ruler’s authority, similar to what had taken place in China and Korea. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

Buddhism After Prince Shotoku

Lotus sutra by Shotoku

Kawagoe wrote: “ Before the Soga leader’s death, the Buddhism that was practiced in the capital had the stamp of the Soga clan on it as it had been the key patron of Buddhism and the ujidera temple complexes were in the control of the Soga clan. After his death however, actions were taken to sever established Buddhist temples from Soga patronage and the control of temple complexes was placed under the charge of emperors and empresses instead. This marked the beginning of the period known as ritsuryo Buddhism. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

“A few days Soga no Iruka’s death, according to Nihon shoki, Emperor Kotoku assembled members of the imperial family and his ministers and made them swear an oath that under heaven there is only one imperial way. In all the imperial messages sent to governors of the eastern provinces, their contents began with an affirmation of kami worship and the emperor’s divine authority, “in accordance with the charge entrusted to me by the heavenly kami“.

“While affirming his divine priestly role as emperor, Emperor Kotoku also sent a message to the “great Buddhist temple” (either Asuka-dera or Kudara Taiji (the Great Paekche Temple, later named Daian-ji) founded by Emperor Jomei in 639 where priests and nuns listened to his edict, the last part of which emphasized the new steps of imperial control and patronage: “… we appoint the following [ten] Buddhist masters … Emmyo [the last named master] is also appointed chief priest of Kudara-dera. The ten Buddhist masters are to give special attention to teaching and guiding all other Buddhist priests and to making certain that Buddhist teachings are practiced in accordance with the law. If anyone below the emperor down through the provincial governors has problems handling the administration of a temple, he is to receive assistance from us. Temple commissioners [tera no tsukasa] and chief temple priests [tera shu] will be appointed. They are to visit temples, ascertain the conditions of priests and nuns and slaves, assess the productivity of temple fields, and take full reports to the throne.”

“Immediately following the edict, three secular officials’ were apponted Buddhist superintendents (hozu). Together with the ten Buddhist masters who were heavily influenced by Tang-learning (at least four had returned from several years of study at Chinese temples), these Chinese trained masters were at the forefront of the movement that transformed Soga Buddhism into the state religion, the type of Buddhism that was flourishing in China at the time. Thus attempts to limit the influence of pro-Paekche clans can be seen with the transfer of patronage of Buddhism from the head of the immigrant Soga clan to the emperor whose authority was derived from his position as chief priesthood of kami worship. Japanese Buddhism was in fact becoming more like Silla’s brand of Buddhism. Silla at the time was the most powerful Korean state, with close ties to the Chinese Tang empire. Many of Japan’s China-trained priests had returned home via the Silla route. Thus, it is assumed there was considerable influence from the increasingly powerful Silla kings who were reinforcing their sacred authority with the worship of Buddha.”

“Even though Prince Shotoku had promoted universalist and humanistic ideals of Buddhism, Buddhism appeared to prosper in its popular magical forms, as support for the state. The new leaders including Emperor Tenji did not seem to be interested in the more intellectual ideas of Buddhism, focusing instead on Buddhist practices that promised this-worldly benefits. Hence, more commonly seen were the holding masses (hoe) at court, makign of Buddhist images, preparing Buddhist meals, and conducting the colorful “burning-of-lamps” (nento) rite. When Emperor Tenji fell seriously sick in 660, one hundred Buddhist images, according to Nihon shoki, were dedicated at court and that the emperor sent messengers to make valuable offerings to Buddha.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons,

Text Sources: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ; Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo ++; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated December 2023