CULTURE IN THE ASUKA PERIOD

Asuka-era men’s clothes Japan’s current culture has its roots in the cultural design of the Asuka era. During this period great structures and sculptures in what is referred to as Asuka style were erected. Clues from of ancient Asuka’s culture can be gleaned from the archeological remains of Asuka’s many temples including the Asukadera temple, Horyuji temple in Ikaruga, and that of Yamadadera Kairou as well as from ancient historical records. The Asuka style eventually gave way to the Hakuhou and Tenpyo styles.

During the Asuka period official delegations, engineers, builders, Buddhist priests, sculptors, medical experts and other came to Japan from Korea. Goods from Central Asia made their way to Japan on the Silk Road. Mahayana (Greater Vehicle) Buddhism was introduced in the Asuka period. Mahayana religious themes would endure for over 500 years. The introduction of Mahayana Buddhism marked the beginning of the development of Japanese fine arts. At this time artisans turned their attention from ceramics and metalworks to Buddhist images, namely sculptures.

The earliest works of sculpture were created by Korean artisans. Example of their work remain at Horyuji Temple in Nara and Koryuji Temple in Kyoto. Among the important cultural legacies of the Asuka period is “Manyoshu”, a literary treasure containing more than 4,500 poems which provide much evidence on how people lived at that time.

Christal Whelan wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The Nihon Shoki describes how the 33rd emperor of Japan — Empress Suiko (A.D. 554-628) — employed Korean artisans to build a garden that would feature a miniature version of the island-mountain Sumeru of Buddhist cosmology. While the Empress' commission surely expressed her exemplary faith, a type of garden known as the "Pure Land Garden" later became fashionable during the Heian period.”

Websites: Yamato Period Wikipedia article on the Yamato period Wikipedia article ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindexList of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Buddhism and Prince Shotoku onmarkproductions.com ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org . References: 1) The Chronicles of Wa, Gishiwajinden by Wes Injerd; 2) Wa (Japan), Wikipedia; 3) Excerpts from the History of the Kingdom of Wei, Columbia University’s Primary Source Document Asia for Educators. Asuka Wikipedia article on Asuka Wikipedia ; Asuka Park asuka-park.go.jp ; Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage sites ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Essay on Early Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ASUKA PERIOD (A.D. 538 TO 710) factsanddetails.com; EARLY BUDDHISM AND POLITICAL STRUGGLES IN ASUKA-ERA JAPAN factsanddetails.com; PRINCE SHOTOKU factsanddetails.com; TAIKA REFORMS AND EMPERORS TENJI AND TENMU factsanddetails.com; ASUKA GOVERNMENT AND ECONOMY AND THE RITSURYO SYSTEM factsanddetails.com; ASUKA, FUJIWARA AND ASUKA-ERA CITIES AND TOMBS factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ARCHITECTURE: PALACES AND BUDDHIST TEMPLES factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ART factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan” (2008) by Donald F. McCallum Amazon.com; “A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” by William E. Deal, Brian Rupper Amazon.com; “Plotting the Prince: Shotoku Cults and the Mapping of Medieval Japanese Buddhism” by Kevin Gray Carr Amazon.com; “Nihongi: Volume I - Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697" by W G Aston Amazon.com; “The Kojiki: An Account of Ancient Matters” by no Yasumaro Ō and Gustav Heldt Amazon.com; “Man'yoshu” by Alexander Vovin Amazon.com; “Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan” by William Wayne Farris Amazon.com;“The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Koji Mizoguchi Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Companion to Japanese Archaeology (Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology)” by Werner Steinhaus, Simon Kaner, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan” by Gina L. Barnes Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan” (Volume 1) by Delmer M. Brown Amazon.com

Adoption of Chinese Script in Japan

Lotus sutra by Prince Shotoku

The Chinese system of writing was introduced to Japan in A.D. 405. Later modifications were made because Chinese characters don't adequately reflect the pronunciations of Japanese speech. Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: “Although Chinese characters inscribed on swords and bronze mirrors are the only surviving physical evidence that writing existed in the Kofun period, the find of two inkstone slates excavated in Matsue, Shimane Prefecture dating further back to the Yayoi period between A.D. 100 and 200, suggests that writing may have been first introduced in those early times. Inscriptions on 5th century swords show that the first writing in Japan was in the Chinese language and that Chinese characters were used to spell out Japanese names. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

“The Nihon shoki chronicle also makes references to officials holding the title of scribes so that we know that their writing and recording skills were highly valued during the Yamato and Kofun periods. The developing centralized state of Yamato required accurate records of various types in order to increase its income and state control over its people. At first, writing in Japan was carried out by immigrant scribes who wrote Chinese, but during the 7th century, a small number of Japanese scholar-aristocrats also started reading and writing Chinese, for official and business purposes and also for the study of Confucian classics and Buddhist texts. The beginning of literacy is ascribed to the arrival of the scholar Wani from the Korean kingdom of Paekche during the late 4th or early 5th century. Wani is recorded as having arrived in the sixteenth year of Ojin, and was appointed tutor of the crown prince, supplementing another man from Paekche called Achiki who had accompanied a gift of a stallion and a mare in the preceding years. Achiki had recommended Wani as the superior scholar upon which the Japanese court had asked for Paekche to send him.

“Wani, who is said to have arrived with 11 volumes of Chinese writings, including the Analects and the Thousand-Character Classic, stayed on in Japan and became the ancestor of a specialized occupational be or group of scribes, the fumi no obito. The establishment of a special secretariat service for the Japanese court suggests that literacy remained at a marginal level during the 5th and 6th centuries and the skills were likely confined to immigrant groups and their descendants. Writing and learning of the Chinese classics had thus been introduced to Japan by early 5th century.

In the abstract of a paper called “The origin of man’yogana”, John R. Bentley wrote: “Most scholars in Japanese studies (history, linguistics, literature) tend to accept in one form or another the ancient legend that the phonetic writing system of ancient Japan, known as man’yogana, came from Paekche. This legend about the ancient Korean kingdom—Paekche—appears in the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, Japan’s two oldest chronicles. To date there have been few attempts to use concrete data from the peninsula either to prove or reject this legend. This article supplies information from all epigraphic data on the Korean peninsula to show that Paekche spread the use of Chinese (sinographs) to be used phonogrammatically and that Koguryo educated the rest of the peninsula in the use of this script. [Source: “The origin of man’yogana” by John R. Bentley, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59-73. School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London]

Literacy and Early Buddhism and Confucianism in Japan

Emperor Shotuku

Kawagoe wrote: “The real push for literacy is likely to have come in the 6th century in connection with the introduction of Buddhism and Confucianism. The need to read, understand and study the Buddhist scriptures and to copy the sutra texts gradually turned the elite and nobles of Japanese society into a literate class. In the 6th century, the Japanese court set up a system of visiting professors in various aspects of Chinese learning via the Korean state of Paekche.

“Eventually, a literary culture evolved following increasing mastery of kambun Chinese prose and the urgent need to represent Japanese words. Japan’s earliest scholar-statesman Prince Shotoku (574-622) had composed the text of his Seventeen Injunctions of 604 in kambun Chinese prose and displayed familiarity with 15 different Chinese works. In 7th century – interest in chronicling work and codifying laws intensified. In 620, Shotoku together with Soga no Umako compiled the first Japanese history of which is recorded in the Nihon shoki – the history was lost partly in the fires of the coup d’etat of 645 and partly in the disturbances of the Jinshin war of 672. In 680s, Emperor Temmu ordered the work of the writing of histories to begin again … which culminated in the production of two surviving history chronicles, the Kojiki (712) and the Nihon shoki (720).

“At about the same time (7th century), poetry that was traditionally in oral form began to be written down – this composition of Chinese poetry (kanshi) in Japan contributed to a more sophisticated phase in the development and evolution of the Japanese writing system. Poetry, some of which had their beginnings in the Asuka-Nara periods, have survived in two works of the 8th century: the Kaifusho (751) and the Manyoshu (759), the earliest extant anthology of Japanese verse. The numerous poems of the Kojiki and Nihon shoki are spelled out character by character, each graph with a phonetic value – so that ancient songs are preserved in the exact phonetic notation and with the original sound value. However, during this phase, the early works, especially evident in the Manyoshu work, the use of phonetic characters was highly variable and changeable showing the early evolution of the Japanese writing and language.”

Korean Influence on Chinese Language Links with Japan

Han Mokkan

A symposium held at the National Museum of Japanese History in December 2013 made it clear that ancient Korea played a significant role in the importation and development of Chinese characters (kanji) and other types of letters in Japan. Yuki Ogawa wrote in the Asahi Shimbun, At the symposium in Tokyo, Japanese researchers announced the results of more than a decade of joint studies with their South Korean peers. Wooden plates bearing kanji previously considered unique to Japan– “hatake” (fields) and “awabi” (abalone)–had been already uncovered in South Korea. Letters written on wooden strips indicated that Baekje, a kingdom that existed from the fourth century to the seventh century, had an arrangement similar to Japan of charging interest payments for loans of rice. [Source: Yuki Ogawa, Asahi Shimbun, February 1, 2013 ^/^]

“The symposium said material has been found showing that a certain kanji was pronounced the same in Japan and in ancient Korea. The kanji in question is “ru.” That is part of the name of a prince, Wakatakeru, inscribed on an iron sword unearthed at the Inariyama ancient tomb in Saitama Prefecture. The same kanji–with the same pronunciation–also appears as part of the name of an individual written on a wooden plate dating to the mid-seventh century in Baekje. “The same kanji was assigned the same sound because Japan and Baekje might have shared part of their cultures,” said Minami Hirakawa, director-general at the National Museum of Japanese History. ^/^

“He also said many Korean migrants were involved in literary activities in ancient Japan. “There were many ruins related to letters in areas known as home to a large population of ‘toraijin,’ such as Gunma Prefecture, where the Tago monument is located,” Hirakawa said, referring to migrants from the Korean Peninsula and China who settled in Japan in the fourth to seventh centuries. The Tago monument, with its inscriptions, is considered one of the three most important ancient monuments in Japan in terms of calligraphy. Gunma Prefecture is located north of Tokyo. Sungsi Lee, professor of Korean culture at Waseda University, said at the symposium that Buddhist monks and students from ancient Korean kingdoms played a big part in the development of Japan’s letter culture by having audiences with Prince Shotoku (574-622) and other key Japanese figures.” ^/^

Asuka Tomb Inscriptions

From the latter part of the 7th century through the end of the 8th century, it was a common practice, in imitation of Chinese custom, to place epitaphs (boshi) inside of tombs. These epitaphs consisted largely of chronological resumes of the lives of the deceased, recorded on silver or bronze strips of metal, rectangular tiles. cinerary urns, and the like. [Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

From this inscription on the epitaph of the tomb of Ono-no-Emishi. son of Ono-no-Imoko, poet and emissary to Sul China, we learn that Emishi held the post of Dajokan (prime minister) in the service of Emperor Tenmu, conjointly with the post of chief administrator (chokan) of the Ministry of Justice (kyobusho) . He died in 677 (the 5th year of Tenmu’s reign) and was posthumously awarded the rank of daikin-jo. The epitaph was unearthed from , Ono-no-Emishi’s burial site (an inhumation grave) on the hill be-hind the Sudo Jinja in Kyoto.

One cinerary urn contains an epitaph belonging to the tomb of Fumi-no-Nemaro, a general of immigrant descent who was active in support of Tenmu during the Jinshin Disturbance (672). He died in the year 700. The cinerary urn is made of green glass and was placed within a gilt bronze vessel. The inscription was placed inside a box,also of gilt bronze.

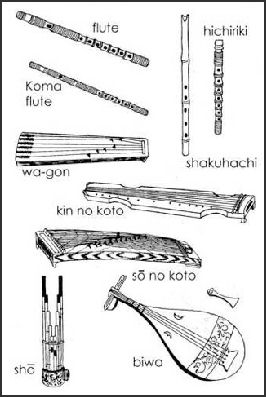

Ancient Japanese Music

8th century court instruments According to Columbia Music Entertainment: “ Almost nothing is known about music in Japan’s prehistory, through the Jomon and Yayoi periods, but there are ritual figures of musicians, suggesting the early importance of music. The late Yayoi period is marked by the building of immense tombs, and there were probably many powerful clans that gradually culminated in the dominance of the Yamato clan. The state that they built used language, religion and legal systems from the Asian continent and resulted in the high development of the imperial court as a political and cultural center in the Nara (645 - 710) and Heian (794 - 1185) periods. Even when the political power of the imperial court declined after this time, the court retained its cultural traditions, many which continue to this day. [Source: Columbia Music Entertainment, 2002]

The little that remains from the prehistoric period seems to be some songs, legends and rituals recorded in the "Kojiki" and "Nihon Shoki," the first chronicles of the new state. When the "Kojiki" was compiled during the reign of Emperor Temmu (reigned around 673 - 686), these songs were already part of the tradition of the imperial court.

From the earliest stages of Japanese history, poetry and song have been very important and the distinction between the two is not clear. The word "uta" can mean either "song" or "poem." What is clear is that poetry is almost always imagined as being recited aloud. The Nara and Heian periods set the standards for poetry with the imperial anthologies Manyoshu and Kokinshu. The forms of verse and use of poetic images developed at this time lives through almost all of Japanese music to the present.

Poetry and music are also central to the prose works of the time. Genji Monogatari is the story of a great lover in the imperial court and much of the dialogue is in the form of exchanges of poetry. The dances of Gagaku, flute, koto and biwa lute music runs through the background of this classical novel. Much of Japan’s official culture was in Chinese, but the Chinese and Japanese languages are very different. Chinese is monosyllabic and has tones, while Japanese has long polysyllabic words and does not have tones. Chinese was used both in the original pronunciation and with various techniques for reading it with Japanese words, but pure Japanese literature in the Heian period and especially Japanese poetry, tried to avoid words of Chinese origin as much as possible.

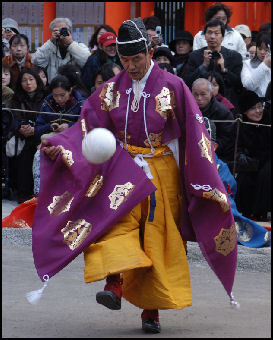

Kemari

Kemari is a traditional form of kickball played by a circle of players that resembles kicking around a soccer ball or hackey sacked in a circle. Performed at a famous Shinto shrine in Kyoto after New Year by men in colorful, dress-like, traditional costumes, it is a simple game: the object is to kick a ball as many times as possible without letting it hit the ground. The 130-gram ball is made of deerskin patched together with horse hide “tape” and covered with a mixture of egg white, glue and white powder.

Kemari is thought to have been imported to Japan from China between the fifth and seventh centuries. The historical chronicle the Nihon Shoki has a small description if it being played at Hokoji Temple in a village in Nara in A.D. 644. A competitive version of the game — in which two six-member teams kick the ball over a rope without letting it hit the ground on a volley-ball size court — has been resurrected in the Asuka area of Nara. As was true in ancient times contemporary players use a leather ball stuffed with deer fur that produces a dull whack when kicked hard and wear Nara-era clothes. In the Heian Period (794-1192) the game was compulsory for court nobles. In the Kamakura period (1192-133) it was popularized by samurai.

Kemari (also known shukiku) is usually played in a 15-square meter area with four species of forked trees in the corners. Each of the trees — a pine, cherry, willow and maple — is considered a dwelling place of gods. Players shout out the names of the gods who visited Fujiwara no Nariminchi, the Saint of Kemari, There are a number of religious rituals that accompany the sport such as placing the ball in the forks of the trees and saying prayers with it at an altar.

The players are supposed to have an erect posture and keep their arms glued to their side like Riverdancers and the kick the ball with the instep of the foot. The color of the costumes worn by the players indicates their skill level. One player told the Daily Yomiuri, “An ideal flick of the ball contains a moderate spin, makes a clear sound like a tsuzumi spin and should not be too low or too high." Kemari is often played as an exhibition. In 1992, U.S. President George Bush joined in a game and enjoyed it so much he kept Air Force 1 waiting as he kept trying it again and again.

Man'yoshu Poems

Manyoshu poem

Among the important cultural legacies of the Asuka period is Manyoshu, a literary treasure containing more than 4,500 poems which provide much insight on how people lived at that time and their feelings and sentiments. They are regarded literary classics today in the same vein as the great poets of ancient Greece and Rome.

The Manyôshû (Man'yoshu, Manyo Poems) is the earliest existing anthology of poems in Japan. Compiled in the seventh century, it includes both long and short forms. Although the “Manyoshu” is estimated to have been edited by 785, much about how it was compiled is unknown.

A large number of poems having to do with Asuka are preserved in it. Some of the poems that have to do with Asuka were composed by such renowned poets as Kakinomoto-no-Hitomaro and Takechi-no-Kurohito, and others were composed by reigning emperors and empresses of the Asuka Period. Those poems which deal specifically with Asuka begin near the very beginning of the anthology with the poem composed by the Emperor Jomei (593-641) on the occasion of an "inspection of the country" (kunimi) from Ama-no-Kaguyama (one of the "Three Mountains of Yamato," now usually called simply Kaguyama). Many of the poems dealing with Asuka were composed at the time of events and incidents which are also recorded elsewhere in historical sources. Such events include military expeditions to Korea during the reign of the Empress Saimei, various moves of the dynastic residence and the building of the new capital city at Fujiwara, the civil disturbance known as the Jinshin no ran, the uprising of Prince Otsu, and the deaths of various imperial scions. ^ [Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

These historically oriented poems, together with the other poems relating affairs of the heart or describing the natural landscape, enable us to come into contact with the consciousness and feelings of the people of that time. In the times during which the poems of the Man'yosho were being written, the seminal germs of Japanese Literature, seen also in the songs and poems included in the Kojiki and Nihon shoki (quasi-historical and historical records compiled in the early 8th century), were in the process of coming to flower.

Oldest ‘Manyoshu’ Poem Found on 7th Century Wooden Strip

Asuka mokkan

In 2008, Japanese archeologists said that a wooden strip unearthed in 2003 from the Ishigami remains in Asukamura, Nara Prefecture, was inscribed with part of an ancient poem that was later included in the “Manyoshu” anthology and is believed to be oldest of its kind. The Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The wooden strip, known as a mokkan, dating to the late seventh century and bearing the poem written in kanji in the phonetic Manyo style, is 60 to 70 years older than one bearing a pair of “Manyoshu” poems excavated from remains of the Shigarakinomiya palace (742-745) in Koka, Shiga Prefecture. The wooden strip from the Ishigami remains indicates that poems were already being composed in the Asuka period (593-710). [Source: Daily Yomiuri, October 18, 2008 |+|]

“The discovery is of major importance in understanding how “Manyoshu,” the nation’s oldest existing poetry anthology, was compiled. The paddle-shaped wooden strip is 9.1 centimeters long, 5.5 centimeters wide and six millimeters thick. The anonymous poem on the strip, from the seventh volume of the “Manyoshu,” can be translated as, “I hope to see whitecaps lapping at the shore on a calm morning, but the wind doesn’t blow.” |+|

“The wooden strip was removed from the area near a channel during excavation work in 2003 by the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties. Another wooden strip bearing the name of the year, “tsuchinoto u” (679), was discovered near the site, suggesting that the wooden strip is from the same period. Various facilities, including a banquet room where a delegation from the Korean Peninsula was entertained and a government office, are believed to have been built in the Ishigami remains, indicating the poem is likely to have been composed at a banquet. |+|

“Takashi Morioka, an associate professor of Tsukuba University, said: “It’s become clear that composing poems in kanji in the phonetic Manyo style was popular among people of a certain social class in the Asuka period. “The wooden strip provides clues to understanding how people of that time tried to compile poems and how they decided which characters to use to write them.” Prof. Takashi Inukai of Aichi Prefectural University said people might have transcribed a poem they heard at a banquet or maybe wrote a poem to read aloud in the same situation, adding that the wooden strip shows that poems were written with one sound per character in the seventh century.” |+|

Manyosho Poem About Love and Death

Manyoshu poem

Poems from the Manyôshû:

Since in Karu lived my wife,

I wished to be with her to my heart's content;

But I could not visit her constantly

Because of so many watching eyes —

Men would know of our troth,

Had I sought her too often.

So our love remained secret like a rock-pent pool;

I cherished her in my heart,

Looking to after-time when we should be together,

And lived secure in my trust

As one riding a great ship.

Suddenly there came a messenger

Who told me she was dead —

Was gone like a yellow leaf of autumn

Dead as the day dies with the setting sun,

Lost as the bright moon is lost behind the cloud

Alas, she is no more, whose soul

Was bent to mine like the bending seaweed.

[Source: “Pleasures of Japanese Literature,” translated by Donald Keene (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 29-30]

Asuka-Era Poems from the Manyosho

ASUKA: Composed by Yamabe-no-Akahito on ascending "Kamuoka" (most likely ikazuchi-no-oka):

The old capital that also was our teacher

In Asuka

We had intended

To make our visits here always

Thinking it would be without end

And continue from generation to generation

Genryaku

Like the tsuga trees that grow lush Extending their many branches Over the Mimoro no Kamunabiyama The old capital with its hills seen tall And its magnificent river The its magnificent river The mountains especially pleasing to see On a day in spring The streams so especially clear On an autumn night Cranes winging confusedly in sunrise clouds And frogs croaking in the evening mists Now whenever I see the place I cannot but weep aloud Remembering days of old. Man'yoshu 324

Unlike the vapors that rise From Asukagawa’s every pool This longing is not one To be conceived perforce to pass Man'yoshu 325

ASUKAGAWA:

When spring is come

In thick profusion flowers bloom

And with the arrival of autumn

That season’s colors give their cast

Genryaku

To vermillion spears of grain And my heart completely yields Like the duck weed in the rapids Of Asuka’s river that circles as a sash Kamunabiyama whose name recalls sweet sake If this heart must melt as the morning dew Then so let it be Secret mistress for whom I yearn And would meet even openly. --- Man’yoshu 3266

KUMEDERA by Kakinomoto-no-Hitomaro By Karu road Whose name recalls sky-flying [wild geese] Was the village of my love With fond attachment I yearned to visit there Yet if I went too many times. unceasingly People’s eyes would be too many And surely they would come to know. So I pinned my hopes as to a great ship Expecting that, Like vines of the sane-kazura Though parting, surely we should meet again And longed for her only in secret As in an iridescent rock-pent pool When. as if the sun in crossing Had gone into darkness

And the shining moon had hidden in clouds A messenger, with catalpa wand. reported saying That my sweetheart, who had bent to me Like the yielding seaweed in offshore waters Had like a colored autumn leaf Passed on and was no more. Hearing the sound of this sudden report

Aigimi

I was at a loss for what to say or do

But hearing that voice I could not stay

And hoping there might be some human feeling

To allay even the thousandth part of my longing

I Left for the Karu market

That my sweetheart always came to see

But standing to listen, there wasn't heard even

The crying of birds on Unebi hill

And not a single person walked the road

Who even looked like her

So seeing nothing else to do

I only called my sweetheart’s name

And waved my sleeve

— Man'yoshu 207

To seek my love who has lost her way

In colored leaves

Too densely grown on an autumn hill

Which mountain trail to take

I do not know

— Man'yoshu 208

[Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

Asuka-Era Poems by Emperors, Royalty and Court Members

KAGUYAMA: Poem composed by Emperor Jomei, probably around 630 on climbing Kaguyama:

Among Yamato’s clustered hills

It is close-by Ama no Kaguyama

That I climb and stand to view the land

Here and there curls of smoke rise from the plain

And gulls take wing from the lakes. endlessly

Yes. a sweet country it is

This dragonfly isle. this land of Yamato.

--- Man’yoshu 2

YAMATO SANZAN : "Poem of the Three Mountains" by Naka no-Oe (son of Jomei), who later became Emperor Tenji:

That Kaguyama vies with Miminashi

Unebi made the object of their lust

Seems thus to have been since the age of the gods

Things having been so in times long past

It is natural, perhaps, in our own fleeting world

That men contend for wives.

--- Man’yoshu 13

31 -Syllable "answering poem" (hanka): When Kaguyama and Miminashiyama:

Faced each other in duel

'Twas I namikunihara

Where [the god of Abo] came to referee.

--- Man’yoshu 14

MAGAMIHARA: Snow poem by the daughter of a palace attendant:

On Magami plain

Of big-mouthed wolves

Oh snow that falls

Fall not so wantonly

When there is no house for shelter.

--- Man’yoshu 1636

[Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

Asuka-Era Poems Related to Emperor Tenmu

OOHARA: Composed by Emperor Tenmu and presented to Lady Fujiwara (one of his consorts):

At my place

A great snowfall there has been

But at your dilapidated old village at Ohara

Later it will fall, if any.

--- Man’yoshu I 03

Tenmu

(The Lady’s reply): It was I who bid the Dragon God In these hills of mine To cause the snow to fall, whereof perchance Some odd bits and pieces got scattered At your place. --- Man’yoshu I 04

In Ohara, old and weathered Village back home I have left my sweetheart there Scarcely can I sleep But let her if she will Appear in my dreams at least. --- Man’yoshu 2587

IWARE-NO-IKE: Poem composed in 686 by Prince Otsu (3rd son of Tenmu) as he wept by the dyke of iware pond, sentenced to die for suspected treason:

Is it today only that I will see these wild ducks crying

Echoing far along iware pond of manifold renown

Before I must depart into hiding with the clouds.

--- Man’yoshu 416

Empress Jito

IKAZUCHI-NO-OKA: Poem by Empress Jito after Tenmu’s death:

Autumn leaves on divine Kamu hill

That our peace-ruling king

Was wont to behold in the evening

And would visit when morning came

Would he not this very day too

Have gone to inquire of them

Would he not then tomorrow as well

Have set his eyes upon them

As I turn my gaze to discern that hill from afar

With the day’s waning I am strangely sad

And when morning comes again

I while away the hours with melancholy heart

And the sleeves of my coarse-cloth robe

Have not the time to dry.

--- Man’yoshu 159

Do they not say there even is a way To wrap a burning flame and put it in a bag? But what enjoyment are tricks like these When there is no way to know his face again?. --- Man’yoshu 160

Between the blue and layered clouds Above the northern hills A star moves off. and so recedes the moon. --- Man’yoshu 161 (Attributed to Jito)

YATSURIYAMA: Composed for Prince Niitabe (son of Tenmu. 673-730) by Kakinomoto-no-Hitomaro:

Our lord who rules in peace

Prince of the high-shining sun

Above the prospering palace

Snow comes and goes

Dispatched by an immemorial heaven

And like the snow

May your rounds continue

Indeed forever.

--- Man’yoshu 261

(accompanying tanka) Yatsuriyama’s stand of trees Nowhere to be seen What fun of a morning To dash through madly falling snow. --- Man’yoshu 262

MINABUCHIYAMA: Poem presented to Prince Yuge (6th son of Tenmu):

Here on crags at Minabuchiyama

Whose name recalls food offerings to the gods

Still unfaded fallen flakes of snow.

--- Man’yoshu I709

[Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

Asuka-Era Haka and Other Short Poems

HINOKUMA: At the Sahinokuma-Hinokumagawa:

If because the shoals are swift

I hold my lord’s hand

What talk about us there may be!.

--- Man’yoshu 1109

SADA:

Not alas that I should have wearied

Of the Shima palace at Tachibana

Do I go to serve night watch

By the side of Sada hill.

--- Man’yoshu 179

KAGUYAMA:

Over Ama no Kaguyama

Whose name recalls the ever-enduring sky

This evening a haze is hung in shelf-like layers

How it does appear spring is upon us!.

--- Man’yoshu 1812 (Anonymous)

SHIMA-NO-MIYA:

The birds we've set free

On the curved pond at the Shima palace

With loving attachment still they yearn

To catch his eye, and this is why their heads

They do not dip their heads beneath its surface.

--- Man’yoshu I 7

[Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp; Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo++; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016