ASUKA GOVERNMENT

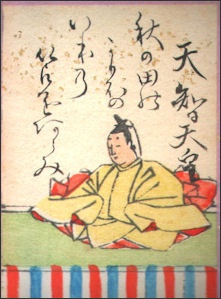

Emperor Tenji

The configuration sought for Japan in the Asuka period was a bureaucratic state with the Tenno (emperor) at the apex, under the rule of law as contained in the Ritsuryo codes (a formal body of penal and administrative laws). From mokkan (wooden documents) recovered at Asuka-ike site, it was verified for the first time that the term "Tenno" traces back to the reign of Emperor Tenmu (r. 673-686). As Tenmu was the ruler who enacted the Asuka Kiyomihara the administrative code, it is fitting to apply the title of "Tenno" to him. Mokkan inscribed with the characters "Tenno" are thus symbols indicating that a political order modeled on the ancient Chinese-style autocratic state had been established by this time. [Source: Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties nabunken.go.jp ]

Charles T. Keally wrote: “The Yamato Government was centered on a Kimi (King), and from the 5th century an Ohkimi (Great King). The title Tenno (Emperor) was used from the time of Temmu (673-686). The government was a coalition of Great Clans. These were the Soga, Kazuraki, Hekuri, Wada and Koze clans in the Nara Basin, and the Izumo and Kibi clans in the Izumo-Hyogo area. The Ohtomo and Mononobe clans were the military leaders, and the Nakatomi and Inbe clans handled rituals. The Soga clan provided the highest minister in the government, while the Ohtomo and Mononobe clans provided the second highest ministers. The heads of provinces were called Kuni-no-miyatsuko. The crafts were organized into guilds. But this whole organization evolved throughout the period; the details are in most history books. [Source: Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, t-net.ne.jp/~keally/kofun ++]

Asuka breezes/ which used to flutter the sleeves/ of lovely ladies/ aimlessly blow on in vain/ now that the court moved away [Manyoshu, book 1, poem 51].Aileen Kawagoe wrote in Heritage of Japan: This poem from Manyoshi, alludes to the custom during the Asuka era, whereby the imperial family by custom resided out of multiple palaces and conducted state affairs from mobile courts. It was the practice for the ruler to build one or more palaces sometimes including a summer palace, or a new palace would be relocated for reasons of ritual cleansing and purity after the death of the previous sovereign. But the practice was expensive and it prevented the development of a stable political order. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

Websites: Yamato Period Wikipedia article on the Yamato period Wikipedia article ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindexList of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Buddhism and Prince Shotoku onmarkproductions.com ; Essay on the Japanese Missions to Tang China aboutjapan.japansociety.org . References: 1) The Chronicles of Wa, Gishiwajinden by Wes Injerd; 2) Wa (Japan), Wikipedia; 3) Excerpts from the History of the Kingdom of Wei, Columbia University’s Primary Source Document Asia for Educators. Asuka Wikipedia article on Asuka Wikipedia ; Asuka Park asuka-park.go.jp ; Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage sites ; Early Japanese History Websites: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Essay on Early Japan aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Japanese Archeology www.t-net.ne.jp/~keally/index.htm ; Ancient Japan Links on Archeolink archaeolink.com ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ASUKA, NARA AND HEIAN PERIODS factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT HISTORY factsanddetails.com; ASUKA PERIOD (A.D. 538 TO 710) factsanddetails.com; EARLY BUDDHISM AND POLITICAL STRUGGLES IN ASUKA-ERA JAPAN factsanddetails.com; PRINCE SHOTOKU factsanddetails.com; TAIKA REFORMS AND EMPERORS TENJI AND TENMU factsanddetails.com; ASUKA, FUJIWARA AND ASUKA-ERA CITIES AND TOMBS factsanddetails.com; CULTURE AND LITERATURE FROM THE ASUKA PERIOD (A.D. 538 TO 710) factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ARCHITECTURE: PALACES AND BUDDHIST TEMPLES factsanddetails.com; ASUKA ART factsanddetails.com; JAPAN AND THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan” (2008) by Donald F. McCallum Amazon.com; “A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” by William E. Deal, Brian Rupper Amazon.com; “Plotting the Prince: Shotoku Cults and the Mapping of Medieval Japanese Buddhism” by Kevin Gray Carr Amazon.com; “Nihongi: Volume I - Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697" by W G Aston Amazon.com; “The Kojiki: An Account of Ancient Matters” by no Yasumaro Ō and Gustav Heldt Amazon.com; “Man'yoshu” by Alexander Vovin Amazon.com; “Sacred Texts and Buried Treasures: Issues in the Historical Archaeology of Ancient Japan” by William Wayne Farris Amazon.com;“The Archaeology of Japan: From the Earliest Rice Farming Villages to the Rise of the State (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Koji Mizoguchi Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Companion to Japanese Archaeology (Comparative and Global Perspectives on Japanese Archaeology)” by Werner Steinhaus, Simon Kaner, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “Archaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilisation in China, Korea and Japan” by Gina L. Barnes Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan” (Volume 1) by Delmer M. Brown Amazon.com

Asuka Economy

fuhon coin

Coins called fuhonsen were also discovered at the Asuka-ike site, a find regarded as rewriting the history texts. No one had suspected that coins bearing Chinese characters were in circulation prior to the minting of Wado kaichin, widely regarded as the oldest currency in Japan. The circulation of money is the heart of an economic policy befitting a unified nation, and its presence lends even greater significance to this formative period of the Japanese ancient state.

Workshops that made carious craft goods were lined up at the Asuka-ike site. The products they handled were not for the common people, but first-class items for decorating the inner sanctuaries and Buddha images of temples, or for use at the palace. The exquisite quality of treasures of the Shosoin, or the craft items and resplendent ornaments which have been handed down at carious temples in Nara is well known, and it is highly significant that detailed information has been found for the first time on the tools and techniques of the artisans who made them, and on the places where they worked.

Implementation of the Taika Reforms

Kawagoe wrote: “The reform created a system for keeping track of households instituted in 670 with the appearance of household registers (koseki) – which was important because for assessing taxes from the land and services from the people. Another important reform involved the nationalization of land. Paddies were henceforth allocated centrally by the government: every 6 years, all free adult males received 0.3 acres, females 0.2 acres. The tribute collection system was also revised. Tribute used to be collected based on the area of land cultivated by a household until 680, but thereafter tribute was collected from individuals. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

The implementation of the district system. Before 673, local affairs were administered by the clan chieftains but after that date, the local sixty provinces were divided into districts (kori) containing villages (sato) of 50 households each, all coming under the jurisdiction of the imperial court. Another reform involved required taxation in the form of produce, in addition to corvee labour. Conscript duty was imposed and each household had to send one young male conscript. Unauthorized weapons were confiscated from all over outlying provinces to prevent insurgencies.

Ritsuryo System

Empress Jito

The Taika Reform mandated a series of reforms that established the ritsuryo system of social, fiscal, and administrative mechanisms of the seventh to tenth centuries. Ritsu was a code of penal laws, while ry was an administrative code. Combined, the two terms came to describe a system of patrimonial rule based on an elaborate legal code that emerged from the Taika Reform. [Source: Library of Congress *]

After the death of Soga no Emishi in 645, the rulers and administrators in Asuka adopted reforms that led to the formation of a Chinese-style state known as the ritsuryo state. Measures were taken to increase the emperor’s autocratic power by making Buddhism a state religion. Buddhist temples and Buddhist worship were used in support of the ruler’s authority, similar to what had taken place in China and Korea. Compilation of the Ritsuryo legal code and official historic chronicles began in 681.

Kawagoe wrote: “ Before the Soga leader’s death, the Buddhism that was practiced in the capital had the stamp of the Soga clan on it as it had been the key patron of Buddhism and the ujidera temple complexes were in the control of the Soga clan. After his death however, actions were taken to sever established Buddhist temples from Soga patronage and the control of temple complexes was placed under the charge of emperors and empresses instead. This marked the beginning of the period known as ritsuryo Buddhism. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

The ritsuryo system was codified in several stages. The mi Code, named after the provincial site of Emperor Tenji’s court, was completed in about A.D. 668. Further codification took place with the promulgation by Empress Jito in 689 of the Asuka- Kiyomihara Code, named for the location of the late Emperor Temmu’s court. The ritsuryo system was further consolidated and codified in 701 under the Taiho Ritsuryo (Great Treasure Code or Taiho Code), which, except for a few modifications and being relegated to primarily ceremonial functions, remained in force until 1868. The Taiho Code provided for Confucian-model penal provisions (light rather than harsh punishments) and Chinese-style central administration through the Department of Rites, which was devoted to Shinto and court rituals, and the Department of State, with its eight ministries (for central administration, ceremonies, civil affairs, the imperial household, justice, military affairs, people’s affairs, and the treasury). A Chinese-style civil service examination system based on the Confucian classics was also adopted. Tradition circumvented the system, however, as aristocratic birth continued to be the main qualification for higher position. The Taiho Code did not address the selection of the sovereign. Several empresses reigned from the fifth to the eighth centuries, but after 770 succession was restricted to males, usually from father to son, although sometimes from ruler to brother or uncle. *

Evolution of the Ritsuryo Controls

Han mokkan

After the 4th and 5th centuries, the moving forces behind the country’s politics at the "center" were a number of powerful and near-autonomous wealthy families (gozoku), of which the most important, at least for ceremonial purposes, was the house of the ruling emperor. Around the middle of the 6th century, effective power was largely In the grip of two clans, the Mononobe and the Soga, but after 587, when the Mononobe Were purged from their position of shared oligarchy about the dynastic house, administration tended to be monopolized by the Soga. and at the same time the Asuka region emerged more and more unequivocably as the country’s administrative and cultural center. [Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

Conditions in China came to be better known through the medium of envoys to the Sui and Tang capitals, and as Sui and Tang power began to extend into Korea, there appeared In Japan new movements which were opposed to this and other international and domestic trends, and which aimed at throwing off old structures and building a stronger and more durable Japanese state.

In 645 (first year of the Taika Reform), the Soga clan was brought down from its position of power by a coalition led by Nakatomi-no-Kamatari and Prince Naka-no-Oe, thus heralding the end of an age of domination by near-autonomous gozoku. Prince Naka-no-Oe (who later became Emperor Tenji, reigning 668 671)and his associates, while on the one hand pursuing armed struggles on the Korean peninsula against Tang and Silla (southeastern Korean) forces. sought on the other hand to build a new state which would make use of administrative systems adopted from China. The latter task was for the most part completed during the reigns of Tenmu (672 686) and his wife Jito (686 697).

The Chinese-inspired ritsuryo system of penal and administrative law was established as the country’s fundamental legal code, and the general body of the populace, which had throughout the country lived under domination by near-autonomous gozoku, became subject to the control of the central administration, through the intermediary of offices for that purpose established In the capital region and in the outlying provinces. The Fujiwara capital (Fujiwara-kyo), completed for occupancy in 694 (the 8th year of Empress Jito’s reign),may be said to have been at the same time intended as a sort of monument to commemorate what was thought of as the completion (nominally, at least) of a nation-state operating under the new regulations of the ritsuryo system.

The book “Ancient Japan, Archaeology for State Formative Processes” by Tetsuo Hishida argues the state formation and Ritsuryo system began in the 5th century not the 7th century. In a review of the book, Hiroyuki Kaneko wrote: “This book is on archaeological study of the state formation history of ancient Japan. It criticizes the historians’ past state formative history, which starts with the Ritsuryo nation in the latter half of the 7th century. It instead proposes that an early nation state was already formed in Japan in the latter half of the 5th century, which developed and evolved into the Ritsuryo nation. Although it was somewhat unsatisfactory that it did not point out that the formation of the Ritsuryo nation resulted from an East Asian upheaval that began with the formation of the Sui and Tang dynasties, this book consisted mainly of a narration of silent archaeological data, with added historical documents and accounts from Chinese history books. The process of making archaeological data historical data, various procedures, and demonstration are minute, and the conclusion is generally appropriate. The future of nation state formative history will progress based on the framework indicated in this book. [Source: Nihon Kôkogaku, May 20, 2008; 117p.]

Household Registers (Koseki) and Wooden Documents (Mokkan) in the Asuka Period

modern koseki

Under the ritsuryo legal system, household registers (koseki) listing each person in the country were compiled to serve as the basis for levying taxes and conscripting soldiers. During the period of the Fujiwara capital when the ritsuryo system was being perfected, the principle was established of compiling household registers once every six years. [Source: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp]

As the ritsuyo legal system took shape, it became more and more common for government offices to use written records in the handling of administrative affairs. These written records took the form of wooden tables (mokkan) bearing ink-written Chinese characters such as those which have been discovered at the site of Fujiwara-no-miya and the supposed site of Asuka Itabuki-no-miya. The mokkan were of several types, including documents, labels for goods in transport, and tallies for other classification purposes. ^

They provide important new materials for learning about the culture, finances, organization of government offices and overall administrative system of the time. For example, while it had been known that Japan in the Nara Period was divided into sixty-odd units known as kuni and each of these kuni was divided into several kori, it had not been known when the Chinese character that, during the Nara period, was used to represent kori, first came into use. Through an examination of recently excavated mokkan, it has been established that previous to the Taiho legal code (702),the word kori was written with a different character.

Asuka-Era Coinage

mokkan

The Nihon Shoki contains references to coins in A.D. 683. In 1998, 33 bronze coins from the late seventh century were unearthed in Asukaike ruin at Asuka along with artifacts that suggested a mint was there. The coins are called Fuhonsen, the name of a charm believed used during the Nara Period (710-784). These “Fuhonsen coins” are regarded as the oldest form of minted currency in Japan.

According to Japanese Coins: ” One of the oldest histories of Japan, the Nihon Shoki of 720 AD, indicates that metal coins were used in 487 AD, but whether these came from Korea, China or Japan is unknown. It was not until the reign of the Emperor Temmu (Temmu’s reign lasted from 672 until his death in 686) that copper coins were widely circulated. However, as with all of Japan’s historical records pre-700 it is difficult to determine what is accurate history and what is myth-making. It is not until the minting of the Wado Kaichin in 708 that there is undeniable evidence of Japanese coinage.”

An archaeological survey conducted at the Asukaike Ruins in 1998 revealed that the Fuhon-sen coins had been minted in the latter half of the seventh century. The coins were unearthed together with the molds, pots and other instruments used to mint them. The Fuhon-sen coin is thought to be the coin referred to in the following rescript mentioned in the Nihon Shoki (written in 683): “From now on, use the copper coins instead of the silver coins.” The silver coins mentioned in the above rescript are thought to be the Mumon Gin-sen coins, which were unearthed at 15 or more sites in Japan (located primarily in the Kinki area).[Source: Bank of Japan Currency Museum boj.or.jp /=/]

CoinLink reported: According to the Nara institute, six of the 33 coins were unearthed intact, while others were found in pieces. The six intact coins were attached to a bronze lattice, showing that they were minted at the site and had not yet been circulated, it said. Each coin is round and measures about 2.5 centimeters in diameter, with a 6-7 millimeters square hole in the center – about the same size as a Wado Kaichin [See Below]. The front carries two vertically aligned kanji characters – “fu” for “wealth” and “hon” for “basis” – flanked by a group of seven dots on each side. The national institute’s Hiroyuki Kaneko said the design is similar to China’s Yosho coins, which were also used as charms. He said those who were involved in minting the coins may have modeled them after Chinese coins that were available from Silla, one of the three ancient Korean kingdoms. [Source: CoinLink, March 17, 2008 ***]

Wado Kaichin (Wadokaichin, Wado-kaichin or called Wado-kaiho) coins are the oldest official Japanese coinage, having been minted starting in A.D. 708 on order of Empress Gemmei. The coins, which were round with a square hole in the center, remained in circulation until A.D. 958. "Wadokaichin" is the reading of the four characters printed on the coin, and is thought to be composed of the era name Wado ("Japanese copper"), which could alternatively mean "happiness", and "Kaichin", thought to be related to "Currency". This coinage was inspired by the Tang coinage named Kaigentsuho (Chinese: Kai Yuan Tong Bao), first minted in Chang'an in A.D. 621. The Wado Kaichin had the same specifications as the Chinese coin, with a diameter of 2.4 centimeters and a weight of 3.75 grams. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to CoinLink: “The Nihon Shoki, the oldest official history of Japan, printed in 720, states that “bronze coins were issued for the first time” in 708. But the Japanese chronicle also suggested that bronze coins existed in the late seventh century, and this had left archaeologists perplexed... The coins discovered in August 1998 at the Asukaike Ruins in Asuka, are older than the Wado Kaichin coins first minted in 708, thus bumping them from the archaeological record books as the nation’s first circulated money... During the Edo Period (1603-1867), Fuhonsen coins were considered play money, and similar coins were made for charms, experts said. Prior to the discovery at the Asukaike Ruins, five Fuhonsen coins were found in 1985 at a dig on the former site of Heijokyo in today’s Nara city, which served as the nation’s capital during the Nara Period. Since these were found to be from the Nara Period, archaeologists had believed they were cast in the same period as Wado Kaichin coins and used as offerings in religious rites and decorations for burials. ***

Background Behind Asuka-Era Coinage

The ritsuryo code-based government, while actively assimilating social systems and culture from China, minted the Wado Kaichin coin in 708, which was modeled after the Kai Yuan Tong Bao coin of the Tang Dynasty. The mintage was regarded as an essential tool for the Japanese government to display the independence and the authority of the nation, both inside and outside the country. The government strived to expand the use of the coins through various measures such as rewarding those who had saved a large number of coins with a court rank. The government used the coins to cover the costs of building the Heijo imperial palace. Face value of the coins was higher than the actual value of the metal they were composed of; therefore the government could earn seigniorage from the mintage. [Source: Bank of Japan Currency Museum boj.or.jp /=/]

According to to CoinLink: The time at which Fuhonsen coins were minted falls into the Fujiwarakyo Period (694-710), which is based in modern-day Kashihara, Nara Prefecture, where three sovereigns — Empress Jito Emperor Monmu and Empress Genmei — once held court. The research institute said the 1998 findings prove that Fujiwarakyo was aimed at creating a polity with solid political and economical structures based on the Taiho Code (Taiho Ritsuryo) of 701. [Source: CoinLink, March 17, 2008]

The code consisted of six volumes of penal law (ritsu) and 11 volumes of administrative law (ryo), modeled after the legal code of China’s Tang Dynasty (618-907). The researchers said the coins may have been cast under the order of Emperor Tenmu, husband of Empress Jito. “The coins perhaps did not function well as a monetary unit because the distribution system (in Fujiwarakyo) had not been developed,” said Jun Ishikawa, chief researcher at the Toyo Research Institute of Mint Coins.

7th century copper and antimony coins

The Asukaike Ruins are believed to be a former site for “a national production center” where products related to the Fujiwarakyo court were manufactured under the latest technologies between the late seventh century and the early eighth century. The ruins are located near Asuka Temple, Japan’s first large-scale Buddhist structure, which belonged to the Soga family, a powerful clan in the region until the mid-seventh century.

In 2008, nine Fuhonsen coins were found at Fujiwarakyu, the ancient capital from 694 to 710, in Kashihara, near Asuka. They differed slightly from previously discovered Fuhonsen coins, suggesting there may have been more than one mint in Asuka-era Japan. CoinLink reported: “Minor differences were found in the kanji character “Fu” used on the surface of the coins and a thicker frame surrounding a square hole in the center of the coins. The materials of four of the coins included arsenic and bismuth, and very pure copper. [Source: CoinLink, March 17, 2008]

Oldest Koseki Record Unearthed in Fukuoka

In June 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A wooden strip believed to be the nation’s oldest koseki, or family registration document, has been unearthed at the Kokubumatsumoto site in Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture, the municipal board of education announced. The strip, believed to have been made late in the seventh century, during the Asuka period (592-710), is older than Japan’s currently recognized oldest existing koseki, an artifact from the year 702 that is kept in Nara’s Shoso-in repository. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 14, 2012 ]

“Its discovery also highlights the likelihood that the central government already directly controlled people over wide areas before the Taiho Ritsuryo--the first nationwide law, equivalent the present-day criminal code and administrative and civil laws--was established in 701. Many historians have believed centralized government came fully into being with the law’s enforcement.

“The 0.8-centimeter-thick wooden strip is 31 centimeters long and 8.2 centimeters wide. It bears the character "kori," a word for a local administrative unit used before the enforcement of the nationwide law, equivalent to a present-day "gun," or county. The strip also bears "shindaini," a title established in 685, leading researchers to conclude it was made at the end of the seventh century. Some of the text on the strip reads, "The head of the household is Takerube no Mimaro," and, "His younger sister is Yaome." The names and relationships of 16 members of the same community are described. The strip also bears the terms "seitei," or healthy men aged 21 to 60, and "heishi," meaning soldiers conscripted from among the seitei. According to the researchers, the strip also includes words to describe dividing a household in two and the head of the household before the division.

“From these findings, the researchers believe the information on the wooden strip was an update for the Koinnenjaku, the nationwide family registration system compiled following the 689 establishment of the Asukakiyomihararyo, the legal code in effect prior to the Taiho Ritsuryo law. Kogonenjaku, the family registration system introduced in 670, is believed to be the first such system compiled nationwide, while Koinnenjaku is believed to have been completed by 690. Until the strip’s discovery, none of the original Koinnenjaku records were believed to exist, making the new discovery all the more significant.

“Some place names, such as "Shimanokori" and " Kawaberi," also are written on the wooden strip. Shimanokori is located in the northern Itoshima Peninsula in Itoshima in the prefecture. The researchers believe it is the same area as the place written in the oldest family registration record in the Shoso-in repository. The archaeological site is 1.2 kilometers northwest of the ruins of the Dazaifu regional administrative office, which oversaw the ancient Kyushu region, and about 30 kilometers from Itoshima. The wooden strip was unearthed from strata in a former riverbed during an excavation conducted prior to the construction of a condominium building on the site.

mokkan with translations

Kazumasa Ikeda wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Japan’s early centralized government placed the highest importance on compiling a family registration system. By doing so, the government, supplanting powerful local clans, could gain direct control of the people, collect tax from them and impose laborious work and military services on them. There is no doubt that the completion of such a centralized administrative framework came with the establishment of the Taiho Ritsuryo nationwide law. However, the process of how it was created remains to be learned.

The family registration information on the unearthed wooden strip--which was made under the Asukakiyomihararyo legal code from the reigns of Emperor Tenmu and Empress Jito--includes words meaning "healthy male" and "soldier." This discovery proves that a military-draft system and taxation classification were already in force at that time--before the establishment of the Taiho Ritsuryo law. It also reveals that regional administrative offices regularly kept track of the movement of residents in local areas. [Source: Kazumasa Ikedam Yomiuri Shimbun, June 14, 2012]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Asuka photos Asuka Musuem and Asuka tourist information

Text Sources: Asuka Historical Museum asukanet.gr.jp ; Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo, ++; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016