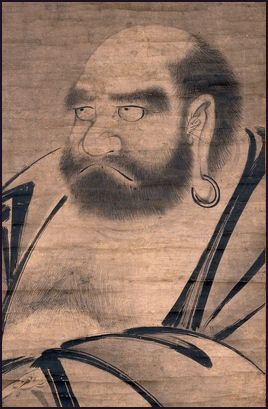

BUDDHIST SCHOOLS IN JAPAN

Daruma, Zen Buddhism founder The are numerous Buddhist sects in Japan. According to 2021 statistics on religion by the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan, 135 million people in Japan were believers, Of these 47 million were Buddhists. The number of believers in each sect were approximately:

1) Jodo Buddhism (Jodo-shu, Jodo Shinshu, Yuzu Nembutsu and Ji-shu) — 22 million.

2) Nichiren Buddhism — 11 million

3) Shingon Buddhism — 5.5 million

4) Zen Buddhism (Rinzai, Soto and Obaku) — 5.3 million

5) Tendai Buddhism — 2.8 million.

The main Japanese Buddhist sects — Shingon, Tendai, Pure Land Nichiren, and Zen — sprung up during the Heian Period (794-1185) and Kamakura Period (1192-1338). The first homegrown Buddhist sects to take hold in Japan were the Tendai and Shingon schools. Only about 700,000 Japanese belong to the old schools, which were established in the Nara period (710 794). Most of these sects are followed by a relatively small group of people today. The sects that grew out of them have larger followings.

For many Japanese, all sects are the same and they have little understanding of the differences between them. Most embrace beliefs of East Asian Mahayana ("Greater Vehicle") Buddhism, which preaches salvation in paradise for everyone rather than focusing on individual perfection as is the case with Theravada Buddhism favored in Southeast Asia. According to some sources the largest sect in Japan in the 1990s was the Nichiren sect with about nine million members. At that time he Zen sect had about 4.5 million members.

Links in this Website: RELIGION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SHINTO SHRINES, PRIESTS, RITUALS AND CUSTOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHISM IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; BUDDHIST GODS, TEMPLES AND MONKS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EARLY BUDDHISM IN ASUKA-ERA JAPAN (A.D. 538 to 710) factsanddetails.com; PRINCE SHOTOKU factsanddetails.com; TODAIJI AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF BUDDHISM IN NARA-ERA JAPAN (A.D. 710-794) factsanddetails.com; NARA-ERA BUDDHIST MONKS, MANDALAS AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; HEIAN PERIOD BUDDHISM (794-1185) factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM AND CULTURE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) factsanddetails.com;

factsanddetails.com;

Buddhist Schools: Buddhist Sects of Japan questia.com ; Wikipedia article on Tendai Sect Wikipedia ; Nichiren Buddhism religionfacts.com ; Jodo (Pure Land) School taichido.com ; Kukai and Shingon Buddhism koyasan.org ; Shugendo shugendo.fr ; Wikipedia article on Yamabushi Wikipedia

Famous Temples: Mt. Hiei and Enryaku-ji Temple Websites: Enryaku-ji is currently the headquarters of the Tendai sect. Enryaku-ji Temple official site hieizan.or.jp ; Kyoto Travel Guide kyoto.travel ; Photos taleofgenji.org ; Marathon monks Lehigh.edu ; Chion-in Temple is the headquarters of the Jodo Buddhist school. Website: Choin-in English site chion-in.or.jp Nishi-Honganji Temple Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Hongwanji hongwanji.or.jp ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” (Wiley-Blackwell Guides to Buddhism) Amazon.com ;

“Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949–1603" by Stephen Turnbull and Wayne Reynolds Amazon.com ;

“Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com;

“Bonds of the Dead: Temples, Burial, and the Transformation of Contemporary Japanese Buddhism” by Mark Michael Rowe Amazon.com ;

“An Introduction to Zen Buddhism” by D. T. Suzuki, David Rintoul, et al. Amazon.com ;

Zen Buddhism: A History (Japan) (Volume 2) by Heinrich Dumoulin Amazon.com ;

“Saicho : The Establishment of the Japanese Tendai School” by Paul Groner Amazon.com ;

“Kukai: Major Works”, Yoshito Hakeda (Translator) Amazon.com ;

“Shingon: Japanese Esoteric Buddhism” by Taiko Yamasaki, more Amazon.com ;

The Pure Land Handbook: A Mahayana Buddhist Approach to Death and Rebirth

by Master YongHua Amazon.com ;

“Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice”

by Charles B. Jones Amazon.com;

“The Three Pure Land Sutras: The Principle of Pure Land Buddhism”

by Jodo Shu Research Institute, Karen J. Mack, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Thus Taught Master Shichiri: One Hundred Gems of Shin Buddhist Wisdom”

by Rev. Gōjun Shichiri and Hisao Inagaki Amazon.com ;

“Nichiren: The Philosophy and Life of the Japanese Buddhist Prophet” (1916)

by Masaharu Anesak Amazon.com ;

“The Lotus Sutra: A Contemporary Translation of a Buddhist Classic”

by Gene Reeves Amazon.com ;

“Transform your energy - Change your life!: Nichiren Buddhism” by Susanne Matsudo-Kiliani, Yukio Matsudo Amazon.com ;

“The Five Eternal Guidelines of the Soka Gakkai”

by Daisaku Ikeda Amazon.com ;

“Encountering the Dharma: Daisaku Ikeda, Soka Gakkai, and the Globalization of Buddhist Humanism” by Richard Hughes Seager Amazon.com

Characteristics of Main Buddhist Sects in Japan

The Buddhism sects in Japan have emphasized the accessibility of salvation and enlightenment of ordinary people. These include: 1) esoteric Buddhism (the Shingon and Tendai sects) that teach mystical practices as a means of apprehending the sacred; and 2) the "Pure Land Sects" that teach that prayer and devotion to Buddhist saints offer a means for salvation, through divine intercession. [Source: Theodore C. Bestor, Countries and Their Cultures, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

3) Zen teaches that enlightenment can be obtained through meditation in which one attains an intuitive spiritual revelation or catharsis through intensive, introspective contemplation, negating the intellect (and the attachments, desires, and obsessions that human thought embodies) precisely through the effort to think through insoluble puzzles of life. 4) The Nichiren sect is one major branch of Japanese Buddhism that does not have close connections to Chinese Buddhist traditions. It developed an intensely nationalistic ideology and a militant orientation to proselytizing that is uncharacteristic of other Japanese Buddhist sects.

"Selective Buddhism" (senchaku bukkyo) refers to cases in which believers were urged to following the teachings of one sect at exclusion of others. For example, advocates of the Pure Land movement advocated abandoning the spiritual practices of bodhisattvas and instead encouraged followers to put their faith in the vow of the Buddha Amida to bring his followers to his Western Pure Land. Similarly, adherents of the Tendai reformer Nichiren strongly criticized other forms of Buddhism and advocated for exclusive adherence to the Lotus Sutra and its teachings. Both of these movements justified the new selective style by claiming that Buddhist history had entered its 'final age' (mappo), a period of spiritual decline during which traditional monastic practices were no longer sufficient for achieving buddhahood. [Source: Carl Bielefeldt, Encyclopedia of Buddhism, Gale Group Inc., 2004]

Types of Buddhism in Nara Period (A.D. 710-794),and Herian Period (794-1185)

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: “Three fundamental types of Buddhism preceded Zen in Japan: 1) the early scholarly sects which came to dominate Nara; 2) the later aristocratic schools whose heyday was the noble Heian era; and, 3) finally, popular, participatory Buddhism, which reached down to the farmers and peasants. [Source: Thomas Hoover, “Zen Culture”, 1977]

The high point of Nara Buddhism was the erection of a giant Buddha some four stories high whose gilding bankrupted the tiny island nation but whose psychological impact was such that Japan became the world center of Mahayana Buddhism. The influence of the Nara Buddhist establishment grew to such proportions that the secular branch of government, including the emperor himself, became nervous. The solution to the problem was elegantly simple: the emperor simply abandoned the capital, leaving the wealthy and powerful temples to preside over a ghost town. A new capital was established at Heian (present-day Kyoto), far enough away to dissipate priestly meddling.

“The second type of Buddhism, which came to prominence in Heian, was introduced as deliberate policy by the emperor. Envoys were sent to China to bring back new and different sects, enabling the emperor to fight the Nara schools with their own Buddhist fire. And this time the wary aristocracy saw to it that the Buddhist temples and monasteries were established well outside the capital — a location that suited both the new Buddhists’ preference for remoteness and the aristocracy’s new cult of aesthetics rather than religion.

“The popular, participatory Buddhism which followed the aristocratic sects was home-grown and owed little to Chinese prototypes. Much of it centered around one particular figure in the Buddhist pantheon, the benign, sexless Amida, a Buddhist saint who presided over a Western Paradise or Pure Land of milk and honey accessible to all who called on his name. Amida has been part of the confusing assemblage of deities worshiped in Japan for several centuries, but the simplicity of his requirements for salvation made him increasingly popular with the Heian aristocrats, who had begun to tire of the elaborate rigmarole surrounding magical-mystery Buddhism. And as times became more and more unstable during the latter part of the Heian era, people searched for a messianic figure to whom they could turn for comfort. So it was that a once minor figure in the Buddhist Therarchy became the focus of a new, widespread, and entirely Japanese cult.

Esoteric Schools of Japanese Buddhism — Tendai and Shingon

Gary Ebersole wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]“The esoteric style developed initially within the schools of Tendai and Shingon but spread widely during the Heian period to influence all forms of Japanese Buddhism. This style was built on a common Mahayana vision of universal buddhahood — universal both in the metaphysical sense that the "dharma body" of the buddha was present in all things and all people, and in the soteriological sense that all people could themselves become buddhas through the realization of this presence. Given such a vision — what scholars sometimes call original enlightenment (Hongaku) thought — the chief religious issue was often cast in terms less of how one might purify and perfect the self than of how one might best contact the realm of universal buddhahood and tap into its power. The new Buddhist movements of the Kamakura period can themselves be seen as variant strategies for answering this question. [Source: Gary Ebersole, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

“Thus, for example, the Pure Land teachings tended to treat the symbol of buddhahood in anthropomorphic terms, as the figure of the Buddha AmitAbha, and to understand the universality of enlightenment as the unlimited power of Amitabha's compassionate concern for all beings. The religious strategy, then, was to access this power by surrendering the pride that separated us from Amitabha, humbly accepting his help, and calling his name (nenbutsu) in faith and thanksgiving. In contrast, the new Zen movement preferred to think of universal buddhahood less in anthropomorphic than in epistemological terms, as a subliminal mode of consciousness shared by all beings. Here, the prime religious problem lay not in pride but in the habits of thought that obscured the enlightened consciousness, and the chief religious strategy was to suspend such habits, through Zen meditation (zazen), in order to "uncover" the buddha mind within.

“For its own part, the esoteric tradition itself tended to conceive of buddhahood in cosmological terms, as the hidden macrocosm of which the human world was the manifest embodiment. An elaborate system of homologies was developed between the properties of the buddha realm and the physical features of Japan, between the deities of the Buddhist pantheon and the local gods of Japan, between the virtues of the cosmic buddha and the psychophysical characteristics of the individual, and so on. The chief means of communication between the two realms was ritual practice — recitation of spells and prayers, performance of mystic gestures, repentance, sacrifice, pilgrimage, and the like — through which the forces of the other realm were contacted and channeled into this world, and the people and places of this world were mystically empowered by (or revealed as) the sacred realities of the buddha realm.

“This cosmological style of religion is often now held up as one of the key unifying forces of Japanese Buddhism, a force that flows across history, from the Heian, through the medieval period, and even into modern times; a force that spreads across the boundaries of clerical and lay communities or elite and popular Buddhism — a force, in fact, that reaches beyond Buddhism proper into Shinto and folk religion, allowing a remarkable freedom of accommodation between the more universal Buddhist vision and the various local Japanese beliefs and practices. The prevalence of this style may help to explain why Japanese Buddhists tend to think of their dead as ancestral "buddha" (hotoke) spirits dwelling in the other world, and why, though the Buddhist denominations today are so sharply divided in formal doctrine and institutional organization, they are so similar in their social function as the intermediaries between the realms of the living and the dead.

Tendai Sect

Saicho, Founder of the Tendai School

The Tendai sect is an eclectic form of Buddhism that incorporates elements of both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. The Lotus Sutra is Tendai’s central text. Followers believe that salvation can be achieved by reciting and copying it.

The Tendai sect appeared at the end of the 8th century and was centered at Enryakuji Temple on Mt. Hiei near Kyoto. Its founder, Saicho (762-822), studied meditation, tantric rituals and the Lotus sutra under the Tient-tai School in China — named after Mt. Tientai in what is now Zhejiang Province — for two years in 804 and 805. When he returned to Japan he found a receptive audience for his message that Buddhist salvation was something that could be achieved by anyone, regardless of class, social status or gender. Saicho is also known as Dengyo Daishi.

Under the patronage of Emperor Kanmu (737-806) and Emperor Saga (786-842) the Tendai sect was officially sanctioned. It was embraced by these emperors who had tired of the authoritarian nature and political power of the priests in the Nara Buddhist sects. Priest were ordained at Enryakuji, the temple founded by Saicho, Tendai artists produced wonderful Buddhist sculpture — graceful and beautiful sculptures of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and deities — in the Heian period.

Tendai was not recognized as a school until after Saicho’s death. After Mt. Hiei received the right to ordain monks the sect took off, At it height Mt, Heie boasted 3,000 temples and 30,000 monks and produced wonderful works of art. The monasteries kept armed retainers and sometimes imposed their will on the government by force.

Almost every sects has its origins in a temple on Mt, Heie. All new sects founded din the 12th and 13th centuries were founded by Tendai monks. Pure Land, Zen and Nichiren all developed from the Tendai school.

See Separate Article TENDAI AND SAICHO factsanddetails.com

Shingon Buddhism

Shingon Buddhism (whose name was derived for the Sanskrit word for "magic formula" or "mantra") is centered at Kongobu-ji Temple at Mt. Koya and To-ji Temple in Kyoto. It is closely linked with the Tendai sect and is known for its ornate art and incorporation of Shinto elements. Today there are 3,700 Shingon-affiliated temples nationwide.

Shingon Buddhism has Tantric elements and is known for it rich ceremonies and has many similarities with Tibetan Buddhism. A central idea is to find the "mystery at the heart of the uncovered — using rituals, symbols and mandalas representing the sphere of the indestructible and the womb of the world.

Shingon Buddhists practice “takigyo” — standing under freezing cold waterfalls at Hakuryu Bentenzan Shumpukuin temple in Mikumocho, Mie Prefecture and the Oiwasan Nissekiji Temple in Kamiichimachi in Toyama, Prefecture as part of an ascetic purification ceremony to mark the beginning of the coldest time of the year. Participants wear white gowns and headbands and chant as they stand under the waterfalls. Sometimes they chant as conch shells are blown. . Sometimes they for stand for over an hour in freezing water.

See Separate Article SHINGON AND KUKAI factsanddetails.com

Pure Land Buddhism

The School of Pure Land (known is Japan as the School of Pure Thought) is another important Chinese school of Buddhism. It emerged about A.D. 500 as a form of devotion to Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and differs from the Ch'an school in that it encourages idolatry. The School of Pure Land is not nearly as strong in China as it once was but it remains one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

The School of Pure Land emerged about A.D. 500 in China as a form of devotion to Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and differs from the Ch'an school in that it encourages idolatry. The School of Pure Land is not nearly as strong in China as it once was but it remains one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

Pure Land Buddhism (also known as Jodo, Jodoshu, or Jodoshinshu) spread during the Kamakura Period (1185 to 1333) but was introduced by the Chinese to Japan much earlier. It emphasizes faith in the saving grace of Amida, another enlightened being, rather than through meditation. Today it has 6 million followers and 7,000 affiliated temples across Japan and has a large following among ordinary Japanese. Pure Land is another word for heaven.

The School of Pure Land takes the Mahayana belief in Buddhas or Bodhisattvas a step further than Buddhist traditionalists want to go by giving Bodhisattvas the power to help people attain enlightenment that otherwise would be unable to attain it on their own. The emphasis on Bodhisattvas is manifested in the numerous depictions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Pure Land temples and caves.

Pure Land Buddhists reveres Amida (literally meaning “infinite light” or “infinite life”), the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and stress the universality of salvation. They believe that salvation is achieved through faith rather than good works and that Buddha and heaven are close at hand and everywhere rather in some far off place as Buddhists had been taught to believe.

See Separate Articles PURE LAND BUDDHISM (JODO) factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTS factsanddetails.com

Nichiren Buddhism

Nichiren Buddhism — the largest of the early sects that remains active today — was founded in the 13th century by Nichiren (1222-82), a Japanese monk who promoted the Lotus sutra as the "right" teaching, and believed that violence was sometimes justifiable. His main claim to fame was predicting the Mongol invasions.

Nichiren Buddhism grew in influence over the centuries. It was based in an interpretation of the “Lotus Sutra”, the central text of text of Tendai and became linked with samurai and the unity of the state and religion. Many present-day Buddhist sects have their roots in Nichiren Buddhism.

Nicheren urged people to chant “Namu myo ho ren ge kyo”—“adoration to the scripture of Lotus Sutra.” The Lotus Sutra affirms that all people, regardless of gender, capacity or social standing, inherently possess the qualities of a Buddha, and are therefore equally worthy of the utmost respect. The Nichiren central doctrine is “ Rissho Ankoku “ which means “spreading peace throughout the country by establishing the True Dharma and uniting society through the Lotus Sutra.”

Based on his study of the sutra, Nichiren established the invocation (chant) of Nam-myoho-renge-kyo as a universal practice to enable people to manifest the Buddhahood inherent in their lives and gain the strength and wisdom to challenge and overcome any adverse circumstances. Nichiren saw the Lotus Sutra as a vehicle for people's empowerment - stressing that everyone can attain enlightenment and enjoy happiness while they are alive.

Nichiren Shu is one of the larger modern Nichern sects. It has 3.8 million members and is led by Rev, Ryokou Koga. The group is currently trying to spread itself more overseas and has temples in 12 countries, including Brazil, Germany, Indonesia, India and the United States and has 16 aid projects going Laos, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, India and Vietnam.

See Separate Article NICHIREN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Zen Buddhism

Zen Buddhism is a Japanese school of Mahayana Buddhism emphasizing the value of meditation and intuition rather than ritual worship or study of scriptures. Zen schools of meditation played a profound role in late medieval and early modern Japan.

Zen Buddhism evolved out of the Ch'an School, a Buddhist sect that was founded in China in the A.D. 8th century. Ch'an is pronounced Zen in Japanese. It means "contemplation" or "mediation." Zen Buddhism was introduced to Japan from China during the Chinese Song Dynasty in the 10th century by a Chinese monk named Huineng. It had a relatively small following for two centuries and didn't take hold and flourish in Japan until the 12th century. The Ch'an sect’s origins are obscure. It is it not clear whether its early patriarchs were legendary or real. Under the leadership of its sixth patriarch Hui-neng (A.D. 637-723) it grew from a cult with around 500 members to a distinct sect after Hui-neng spent 15 years meditating in the hills.

Once Zen Buddhism took hold in Japan had a profound influence on the Japanese. Its austere tone and the simplicity of the doctrine appealed to the military class and artists and was a focal point of samurai culture and art from the 12th century onward. Not only that, Zen Buddhists helped bring Chinese philosophy, especially Neo-Confucianism, to Japan and were involved in commercial endeavors, such as shipping lines, that controlled trade between Japan and China.

See Separate Article ZEN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

Yamabushi

“Yamabushi” are Shugendo mountain ascetics. Also known as “shugenja”, they are members of Esoteric Shingon and Tendai sects of Buddhism. Traditionally they were shaman or hermits with long beards who lived in huts on sacred mountains and endured rigorous training and exercises. Yamabushi means “those who lie down in the mountains.”

Early yamabushi went on long treks and mountain climbs and lived for months and even years in the wilderness. Their training and lifestyle were believed to have given them magical and supernatural powers. Villagers welcomed them so they could perform rituals to prevent earthquakes and other natural disasters and bring rain and good harvests.

Yamabushi seclude themselves in the mountains for months or even years at a time, praying endlessly, performing fire rituals, fasting in caves, and subjecting themselves to various physical and psychological tests, such as hanging headfirst from cliffs and standing under frigid waterfalls. Early yamabushi not only pursued inner enlightenment they also sought magical powers which could used to cure disease and prevent disasters.

See Separate Article Shugendo and Yamabushi factsanddetails.com

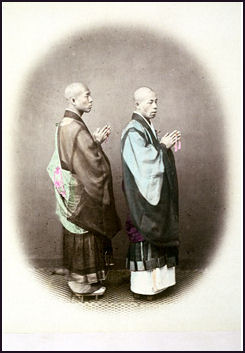

Image Sources: 1) 1st Daruma, British Museum, 2) 2nd daruma, Onmark Productions, 3) Koyasan and diagrams JNTO 4) Monks, Ray Kinnane, 5) 19th century monks and hermit 6) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 7) calligraphy, painting, Tokyo National Museum.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024