SCHOOL OF PURE LAND BUDDHISM

Jodo Buddhism (Jodo-shu, Jodo Shinshu, Yuzu Nembutsu and Ji-shu)is the largest Buddhist sect in Japan with 22 million followers. [Source: 2021 statistics on religion by the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan]

The School of Pure Land (known is Japan as the School of Pure Thought) is another important Chinese school of Buddhism. It emerged about A.D. 500 as a form of devotion to Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and differs from the Ch'an school in that it encourages idolatry. The School of Pure Land is not nearly as strong in China as it once was but it remains one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

The School of Pure Land takes the Mahayana belief in Buddhas or Bodhisattvas a step further than Buddhist traditionalists want to go by giving Bodhisattvas the power to help people attain enlightenment that otherwise would be unable to attain it on their own. The emphasis on Bodhisattvas is manifested in the numerous depictions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Pure Land temples and caves.

Pure Land Buddhists reveres Amida (literally meaning “infinite light” or “infinite life”), the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and stress the universality of salvation. They believe that salvation is achieved through faith rather than good works and that Buddha and heaven are close at hand and everywhere rather in some far off place as Buddhists had been taught to believe. Pure Land Buddhists believe that Amida formed the “Pure Land” once he achieved buddhahood. In turn, followers believe if they devote themselves to Amida they will be reborn in this Pure Land and achieve enlightenment. In a significant revision of traditional Buddhist teachings, Pure Land Buddhism emphasizes trust in the Amida Buddha as the key to enlightenment and places less stress on self-effort. [Source: Joseph W. Williams, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

For information on Chinese Pure Land Buddhism See CHINESE BUDDHIST SCHOOLS AND SECTSSeparate Article: factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

The Pure Land Handbook: A Mahayana Buddhist Approach to Death and Rebirth

by Master YongHua Amazon.com ;

“Pure Land: History, Tradition, and Practice”

by Charles B. Jones Amazon.com;

“The Three Pure Land Sutras: The Principle of Pure Land Buddhism”

by Jodo Shu Research Institute, Karen J. Mack, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Thus Taught Master Shichiri: One Hundred Gems of Shin Buddhist Wisdom”

by Rev. Gōjun Shichiri and Hisao Inagaki Amazon.com ;

“A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” (Wiley-Blackwell Guides to Buddhism) Amazon.com ;

“Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949–1603" by Stephen Turnbull and Wayne Reynolds Amazon.com ;

“Bonds of the Dead: Temples, Burial, and the Transformation of Contemporary Japanese Buddhism” by Mark Michael Rowe Amazon.com

History of the Pure Land School of Buddhism

Pure Land Buddhism (also known as Jodo, Jodoshu, or Jodoshinshu) spread during the Kamakura Period (1185 to 1333) but was introduced by the Chinese to Japan much earlier. It emphasizes faith in the saving grace of Amida, another enlightened being, rather than through meditation. Today it has 6 million followers and 7,000 affiliated temples across Japan and has a large following among ordinary Japanese. Pure Land is another word for heaven. The School of Pure Land emerged about A.D. 500 in China as a form of devotion to Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and differs from the Ch'an school in that it encourages idolatry. The School of Pure Land is not nearly as strong in China as it once was but it remains one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

Peter A. Pardue wrote in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences: The institutionalization of Pure Land in Japan was promoted by three unorthodox Tendai priests, Kuya (903–972), Genshin (942–1017), and Ryonin (1071–1132). Kuya left the monastery to preach to the masses and promote charitable public works. His missionary zeal even moved him to try to evangelize the primitive Ainus. Genshin popularized Pure Land in his book The Essentials of Salvation. Ryonin expounded the teaching in songs and liturgy, intoning the Nembutsu and urging the unity of all men in the faith. His converts included monks, aristocrats, and common laity alike. Subsequent developments were even more radical. Ippen (1239–1289) followed the tradition of personal evangelism, preaching and singing in Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples about the omnipresence of Amida’s compassion with a universalism which transcended all sectarian differences. [Source: Peter A. Pardue, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The sudden increase in the popularity of Pure Land during this period of hardship suggests that for the first time the meaning of the human situation — not merely the immediate conditions of personal well-being — was called into question on a large scale. There was an increasing obsession with the idea that the world is hell and the human situation totally corrupt. Although it is clear that for many the heavenly paradise of the “pure land” was an affirmation of worldly pleasures, there were practices symptomatic of deeper stresses. People of all classes practiced ascetic vigils and fasts while concentrating on Amida’s compassionate image. There were radical acts of physical self-mortification — for example, gifts of a finger, hand, or arm to Amida or religious suicides by burning or drowning — all indicative of deep disturbance.

Honen (1133–1212) and Shinran (1173–1262) were responsible for the major forms of Pure Land, which still exist today. Prior to their efforts the images of Amida were to be found in the temples of almost every sect, and the Nembutsu had no orthodox exclusiveness. But Honen insisted on the inherent superiority of Pure Land. His radical sectarianism and his success in winning converts resulted in persecution and exile. His disciple Shinran went further: man’s total sinfulness means that calling on Amida’s name is a useless effort toward merit making unless it is done out of grace-given faith and gratitude. Suffering and sin are the preconditions for personal salvation: “If the good are saved, how much more the wicked.” Monastic celibacy and the precepts are ineffectual and must be abandoned. The warrior, hunter, thief, murderer, prostitute — all are saved through faith alone. Shinran held that monastic celibacy was not required, and he formed the True Pure Land sect (Jodo Shin) in reaction to some of the more conservative members of Honen’s group, who still held to the celibate ideal and other traditional vows. The new sect was organized around Shinran’s lineal descendants.

One of the consequences of Pure Land radicalism was that it provoked a counterreformation which brought new rigor to the Nara sects and reform movements within Shingon and Tendai. The most important reformer was Nichiren (1222–1282), a Tendai monk born the son of a fisherman, who took deep pride in his low birth and prophetic role. His reforming message was based on a call to return to the teaching of the Lotus Sutra. The goal of his mission was a paradoxical combination of evangelical universalism, radical sectarianism, and fierce nationalism, demanding the cultural and political unification of Japan around Buddhism through faith in the Lotus alone. His position was sufficiently radical for him to form a new school, and his criticism of the incumbent regime resulted in the imposition on him of the death sentence, which was finally commuted to exile. His suffering he interpreted as inherently in keeping with the Buddha’s message, and his disciples continued missionary activity despite continuous persecution, particularly during the Tokugawa shogunate.

The Pure Land sect became very powerful when it was adopted by the ancestors of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), Japan’s first shogun. Ieyasu himself reportedly hand-copied the “nenbutsu“ prayer every day on a small piece of paper. Ieyasu’s descendant turned some of Pure Land temples into military fortresses with cannons, high walls and gates.

Appeal of the School of Pure Land

According to the BBC: “ Pure Land Buddhism offers a way to enlightenment for people who can't handle the subtleties of meditation, endure long rituals, or just live especially good lives. The essential practice in Pure Land Buddhism is the chanting of the name of Amitabha Buddha with total concentration, trusting that one will be reborn in the Pure Land, a place where it is much easier for a being to work towards enlightenment. Pure Land Buddhism adds mystical elements to the basic Buddhist teachings which make those teachings easier (and more comforting) to work with. These elements include faith and trust and a personal relationship with Amitabha Buddha, who is regarded by Pure Land Buddhists as a sort of saviour; and belief in the Pure Land, a place which provides a stepping stone towards enlightenment and liberation. Pure Land Buddhism is particularly popular in China and Japan. [Source: BBC]

“The sect's teachings brought it huge popularity in Japan, since here was a form of Buddhism that didn't require a person to be clever, or a monk, and that was open to the outcasts of society. It remains a popular group in Buddhism - and the reasons that made it popular 700 years ago are exactly the same ones that make it popular today.

Dr. Eno wrote: “Pure Land was a popularized form of Buddhism which preached that salvation could be attained through purely devotional practices, such as the chanting of sutras or brief devotional formulas, the worship of Buddha images, and financial contributions to temples. Pure Land represented a non-intellectual form of Buddhism that appealed most directly to the enormous and illiterate peasant population of China. It taught the poor that through devotion they could escape their lives of misery and be admitted after death to the Western Paradise, the “pure land” where one enjoyed eternal comfort and joy, free of the toils of “ samsara”. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

History of Pure Land Buddhism

Shinran

Some historians believe the School of Pure Land originated in India but there is no definitive proof of this because the oldest known texts are in Chinese not Sanskrit. Others say the sect was founded by the Chinese monk Hui Yuan (A.D. 334-417). In any case as the school became popular in China, images of Buddha and Bodhisattvas acquired Chinese names and statues of the sitting Buddha (in meditation) and the sleeping Buddha (asceticism) were raised all over the country.

According to the BBC: “ Pure Land Buddhism as a school of Buddhist thinking began in India around the 2nd century B.C.. It spread to China where there was a strong cult of Amitabha by the 2nd century CE, and then spread to Japan around the A.D. 6th century. Pure Land Buddhism received a major boost to its popularity in the 12th century with the simplifications made by Honen. A century later Shinran (1173-1262), a disciple of Honen, brought a new understanding of the Pure Land ideas, and this became the foundation of the Shin (true) sect. [Source: BBC]

Pure Land Buddhism took off in Japan when the monk Honen (1133-1212) simplified the teachings and practices of the sect so that anyone could cope with them. He eliminated the intellectual difficulties and complex meditation practices used by other schools of Buddhism. Honen taught that rebirth in the Pure Land was certain for anyone who recited the name with complete trust and sincerity. Honen said that all that was needed was. saying "Namu Amida Butsu" with a conviction that by saying it one will certainly attain birth in the Pure Land.

“The result was a form of Buddhism accessible to anyone, even if they were illiterate or stupid. Honen didn't simplify Buddhism through a patronising attitude to inferior people. He believed that most people, and he included himself, could not achieve liberation through any of their own activities. The only way to achieve buddhahood was through the help of Amitabha.

“A century after Honen, one of his disciples, Shinran (1173-1262) brought a new understanding of the Pure Land ideas. Shinran taught that what truly mattered was not the chanting of the name but faith. Chanting on its own had no value at all. Those who follow the Shin school say that liberation is the consequence of a person achieving genuine faith in Amitabha Buddha and his vow to save all beings who trusted in him.

Rennyo (1415–1499) is regarded as the great unifier of the Pure Land Buddhism (the Jodo Shinshu school). He systematized the doctrines and practices of Jodo Shinshu Buddhism following the death of Shinran.

See Separate Article HEIAN PERIOD BUDDHISM AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Honen

Honen (1133–1212), the founder of Pure Land Buddhism, was originally a Tendai monk. After reading Ljo-yoshu ("The Essentials of Salvation") by the monk Genshin (942–1017), he became convinced that one should seek rebirth in the bodhisattva Amida's Pure Land rather than seek enlightenment through traditional practices. [Source: Gary Ebersole, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Honen made Pure Land Buddhism an independent sect. He eschewed scholarly metaphysics and promoted the use of simple prayers and chants such as "Hail Amida Buddha," as a means to enlightenment. He once said "Even a bad man will be received in Buddha's Land, but how much more a good man!" The idea of hell and judges is important in the Pure Land school of Buddhism.

Honen studied as a Tendai monk at Enryakuji Temple on Mt. Hiei, beginning at age 13, and read the Chinese “Tripitaka” five times and was respected for his learning. He began teaching the Pure Land faith after realizing, at age 43, that the teachings of the Buddhist elite were lacking and that reliance on Amida was the only way to reach enlightenment and it was something that could be obtained by anyone not just pious monks. This message appealed to both the elite and ordinary people but was opposed by the old schools. Honen and his followers were persecuted. At the age of 75 Honen was banished to Shikoku. Some of his followers were executed.

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: What Honen championed was actually a highly simplified version of the Chinese Jodo school, but he avoided complicated theological exercises, leaving the doctrinal justifications for his teachings vague. This was intended to avoid clashes with the priests of the older sects while simultaneously making his version of Jodo as accessible as possible to the uneducated laity. The prospect of Paradise beyond the River in return for minimal investment in thought and deed gave Jodo wide appeal, and this improbable vehicle finally brought Buddhism to the Japanese masses, simple folk who had never been able to understand or participate in the scholarly and aristocratic sects that had gone before. [Source: Thomas Hoover, “Zen Culture”, 1977]

“Not surprisingly, the popularity of Honen’s teachings aroused enmity among the older schools, which finally managed to have him exiled for a brief period in his last years. Jodo continued to grow, however, even in his absence, and when he returned to Kyoto in 1211 he was received as a triumphal hero. Gardens began to be constructed in imitation of the Western Paradise, while the nembutsu resounded throughout the land in mockery of the older schools. The followers of Jodo continued to be persecuted by the Buddhist establishment well into the seventeenth century, but today Jodo still claims the allegiance of millions of believers.

Shinran

Shinran (1173-1262) was one Honen’s favorite disciples. He is regarded as the actual founder of the Pure Land sect in Japan. He renounced the monk’s life and married a young noblewoman, arguing that celibacy and dietary rules demonstrated reliance on self-power. He was banished and spent much of his life in the provinces. His grandson carried on his lineages, which remains alive among his descendants today.

Shinran stressed that absolute faith in the saving power of Amida's bodhisattva vow was the only path to salvation. Like Martin Luther in the West, he rejected the exclusive claims made for the role of priests and their rituals in gaining salvation. He also rejected clerical celibacy. His movement was known as True Pure Land, or Shinshu. [Source: Gary Ebersole, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, Thomson Gale, 2006]

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: Shinran’s interpretation of the Amida sutras was even simpler than Honen’s: based on his studies he concluded that only one truly sincere invocation of the nembutsu was enough to reserve the pleasures of the Western Paradise for the lowliest sinner. All subsequent chantings of the formula were merely an indication of appreciation and were not essential to assure salvation. [Source: Thomas Hoover, “Zen Culture”, 1977]

Shinran also carried the reformation movement to greater lengths, abolishing the requirements for monks (which had been maintained by the conciliatory Honen) and discouraging celibacy among priests by his own example of fathering six children by a nun. This last act, justified by Shinran as a gesture to eliminate the division between the clergy and the people, aroused much unfavorable notice among the more conservative Buddhist factions. Shinran was also firm in his assertion that Amida was the only Buddha that need be worshiped, a point downplayed by Honen in the interest of ecumenical accord.The convenience of only one nembutsu as a prerequisite for Paradise, combined with the more liberal attitude toward priestly requirements, caused Shinran’s teachings to prosper, leading eventually to an independent sect known as Jodo Shin, or True Pure Land.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Hōnen and Shinran were both exiled in 1207 by the government, which objected to the practice of chanting the "nembutsu". “Nembutsu” means “I put my faith in Amida Buddha.” Practitioners believed that by chanting this they would attain salvation.) Shortly after this, Shinran abandoned the "nembutsu" practice, which he then considered self-centered and opposed to the teaching of salvation by Other Power. Shinran married and had children, thus also departing from the clerical life.

Kuya — The Dancing “Saint of the Streets”

According to “Sources of Japanese Tradition”: The rise of Pure Land Buddhism was not merely an outgrowth of the new feudal society, translating into religious terms the profound social changes which then took place. Already in the late Heian period we find individual monks who sensed the need for bringing Buddhist faith within the reach of the ordinary man, and thus anticipated the mass religious movements of medieval times. Kuya (903-72), a monk on Mt. Hiei, was one of these. The meditation on the Buddha Amida, which had long been accepted as an aid to the religious life, he promoted as a pedestrian devotion. Dancing through the city streets with a tinkling bell hanging from around his neck, Kuya called out the name of Amida and sang simple songs. [Source: Wm. Theodore de Bary (ed.),“Sources of Japanese Tradition” (Columbia University Press, 1958), PP. 193-4, [Source: Eliade Page]

One of Kuya’s songs goes:

He never fails

To reach the Lotus Land of Bliss

Who calls,

If only once,

The name of Amida

.A far, far distant land

Is Paradise,

I've heard them say;

But those who want to go

Can reach there in a day.

In the market places all kinds of people joined him in his dance and sang out the invocation to Amida, 'Namu Amida Butsu.' When a great epidemic struck the capital, he proposed that these same people join him in building an image of Amida in a public square, saying that common folk could equal the achievement of their rulers, who had built the Great Buddha of Nara, if they cared to try. In country districts he built bridges and dug wells for the people where these were needed, and to show that no one was to be excluded from the blessings of Paradise, he travelled into regions inhabited by the Ainu and for the first time brought to many of them the evangel of Buddhism.

Amida

According to the BBC: “ The Pure Land sect emphasizes the important role played in liberation by Amida (which means Immeasurable Light) who is also called Amitayus (which means Immeasurable Life). People who sincerely call on Amida for help will be reborn in Sukhavati - The Pure Land or The Western Paradise - where there are no distractions and where they can continue to work towards liberation under the most favourable conditions. [Source: BBC]

“The nature of Amida is not entirely clear. Encyclopedia Britannica describes him as "the great saviour deity worshiped principally by members of the Pure Land sect in Japan." Another writer says "Amida is neither a God who punishes and rewards, gives mercy or imposes tests, nor a divinity that we can petition or beg for special favours". The mystical view of Amida regards him as an eternal Buddha, and believes that he manifested himself in human history as Gautama, or "The Buddha". Amida translates as "Amito-fo" in Chinese and "Amida" in Japanese.

“The story of Amida: Once there was a king who was so deeply moved by the suffering of beings in the world that he gave up his throne and became a monk named Dharmakara. Dharmakara was heavily influenced by the 81st Buddha and vowed to become a Buddha himself, with the aim of creating a Buddha-land that would be free of all limitations. He meditated at length on other Buddha-lands and set down what he learned in 48 vows. Eventually he achieved enlightenment and became Amida Buddha and established his Buddha-land of Sukhavati.

His most important vow was the 18th, which said: If I were to become a Buddha, and people, hearing my Name, have faith and joy and recite it for even ten times, but are not born into my Pure Land, may I not gain enlightenment. Since he did gain enlightenment, it follows that those who do have faith and joy and who recite his name will be born into the Pure Land.

Popularization of Amida by Honen

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: “The popular, participatory Buddhism which followed the aristocratic sects was home-grown and owed little to Chinese prototypes. Much of it centered around one particular figure in the Buddhist pantheon, the benign, sexless Amida, a Buddhist saint who presided over a Western Paradise or Pure Land of milk and honey accessible to all who called on his name. Amida has been part of the confusing assemblage of deities worshiped in Japan for several centuries, but the simplicity of his requirements for salvation made him increasingly popular with the Heian aristocrats, who had begun to tire of the elaborate rigmarole surrounding magical-mystery Buddhism. And as times became more and more unstable during the latter part of the Heian era, people searched for a messianic figure to whom they could turn for comfort. So it was that a once minor figure in the Buddhist Therarchy became the focus of a new, widespread, and entirely Japanese cult. [Source: Thomas Hoover, “Zen Culture”, 1977]

“The figure of Amida, a gatekeeper of the Western Paradise, seems to have entered Buddhism around the beginning of the Christian Era, and his teachings have a suspiciously familiar ring: Come unto me all ye who are burdened and I will give you rest; call on my name and one day you will be with me in Paradise. In India at this time there were contacts with the Near East, and Amida is ordinarily represented as one of a trinity, flanked by two minor deities. However, he is first described in two Indian sutras which betray no hint of foreign influence. During the sixth and seventh centuries, Amida became a theme of Mahayana literature in China, whence he entered Japan as part of the Tendai school. In the beginning, he was merely a subject for meditation and his free assist into Paradise did not replace the personal initiative required by the Eightfold Path.

Around the beginning of the eleventh century, however, a Japanese priest circulated a treatise declaring that salvation and rebirth in the Western Paradise could be realized merely by pronouncing a magic formula in praise of Amida, known as the nembutsu: Namu Amida Butsu, or Praise to Amida Buddha. This exceptional new doctrine attracted little notice until the late twelfth century, when a disaffected Tendai priest known as Honen (1133-1212) set out to teach the nembutsu across the length of Japan. It became an immediate popular success, and Honen, possibly unexpectedly, found himself the Martin Luther of Japan, leading a reformation against imported Chinese Buddhism. He preached no admonitions to upright behavior, declaring instead that recitation of the nembutsu was in itself sufficient evidence of a penitent spirit and right-minded intentions. It might be said that he changed Buddhism from what was originally a faith all ethics and no god to a faith all god and no ethics.

Japanese Pure Land mandala

School of Pure Land Beliefs

The purity referred to in the School of Pure Land is the state a Bodhisattva attains upon achieving enlightenment. Followers of the school believe that impure people can attain their own personal enlightenment by linking themselves with a Bodhisattva, notably Amida (Amitabha), the Buddha who set up and rules over the Western Paradise. Pure Land followers believe that no matter how wicked a person is they can attain a form of enlightenment with simple faith, that is some cases is manifested simply by murmuring a few phrases.

Pure Land Buddhists believe that Buddhism has entered a Mappo (Later Age) in which Buddhism is in decline and individuals are no longer able to achieve enlightenment on their own and salvation can only be achieved by enlightenment through the mercy of Amida. This idea appealed to many ordinary Japanese who were not turned on by an usual process of mediating, chanting and denying oneself for long periods of time.

The idea is that rather than striving for enlightenment by the accumulation of merit through good deeds and morality an individual can be transported with the help of a Bodhisattvas to a “Pure Land” — the Western Paradise of Amida — in his or her next life where attaining enlightenment is profoundly easier than on earth. Amida is said to have the power to grant salvation to all those who have faith in him. The moment a believer places his faith in Amida he or she is said to have attained a measure of enlightenment.

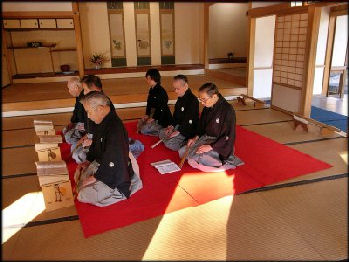

In the school of Pure Land there is a strong emphasis on devotion. Monks are required to go through a head-shaving ceremony. Followers are expected to abandon all desire, even the desire for enlightenment, and entrust themselves totally to the power of Amitabha. Other practices associated with the school are the chanting of the nembutsu, a simple mantra that goes “Namu Amida Butsu” (“Adoration of the Buddha Amitabha”) Shinran's reliance on the power of Amida is emphasized by his reinterpretation of the Nembutsu. A single, sincere invocation is enough, said Shinran, and any additional recitation of the Name should merely be an expression of thanksgiving to Amida.

The religious scholar Richard Robinson wrote that Pure Land and Cha’an. sects “differ markedly in several ways: one is pietst, the other is mystic; one stresses faith, the other insight; one requires absolute reliance on the word of a Scripture, the other relies not on Scriptures but on a special transmission from mind to mind...The Pure Land devotee commonly belongs to the Buddhist typology, to the “tribe of lust," while the Ch’an devotee belongs to the “the tribe of wrath”...But both reject the gradual course and...are essentially “sudden” teachings...Both claim a way to infinite merit."

Pure Land Worship

The Pure Land scriptures include The Infinite Life Sutra, The Contemplation Sutra and The Amitabha Sutra. Chanting the name of Amitabha Buddha does not do anything at all to help the person to the Pure Land. Chanting is nothing more than an expression of gratitude to Amitabha Buddha and an expression of the chanter's faith. But it's not possible to do away with the chanting: Shinran wrote "the True Faith is necessarily accompanied by the utterance of the Name". [Source: BBC]

Nembutsu is an important concept. It “means concentration on Buddha and his virtues, or recitation of the Buddha's name. No special way of reciting the name is laid down. It can be done silently or aloud, alone or in a group and with or without musical accompaniment. The important thing is to chant the name single-mindedly, while sincerely wishing to be reborn in the Pure Land.

Shin Buddhists say that faith in Amitabha Buddha is not something that the believer should take the credit for since it's not something that the believer does for themselves. Their faith is a gift from Amitabha Buddha. And in keeping with this style of humility, Shin Buddhists don't accept the idea that beings can earn merit for themselves by their own acts; neither good deeds, nor performing rituals help. This has huge moral implications in that it implies (and Shinran quite explicitly said) that a sinner with faith will be made welcome in the Pure Land - even more welcome than a good man who has faith and pride.

Honen and Nembutsi — the Invocation of Amida

Honen believed that the invocation of Amida's name — Namu Amida Butsu — was the only sure hope of salvation. This invocation became known as the Nembutsu, a term which originally signified meditation on the name of Amida, but later meant simply the fervent repetition of his name. The wife of the ex-Regent, Kanezane Tsukinowa, already converted to Honen's faith, asked him some questions regarding the practice of Nembutsu. Honen replied as follows:

I have the honour of addressing you regarding your inquiry about the Nembutsu. I am delighted to know that you are invoking the sacred name. Indeed the practice of the Nembutsu is the best of all for bringing us to Ojo,1 because it is the discipline prescribed in Amida's Original Vow. The discipline required in the Shingon, and the meditation of the Tendai, are indeed excellent, but they are not in the Vow. This Nembutsu is the very thing that Shakya himself entrusted 2 to his disciple, Ananda. As to all other forms of religious practice belonging to either the meditative or non-meditative classes, however excellent they may be in themselves, the great Master did not specially entrust them to Ananda to be handed down to posterity. [Source: Translation and notes by Rev. Harper Havelock Coates and Rev. Ryugaku Ishizuka, Honen, the Buddhist Saint, III (Kyoto, 1925), PP. 371-3, Eliade Page]

Moreover, the Nembutsu has the endorsation of all the Buddhas of the six quarters; and, while the disciples of the exoteric and esoteric schools, whether in relation to the phenomenal or noumenal worlds, are indeed most excellent, the Buddhas do not give them their final approval. And so, although there are many kinds of religious exercise, the Nembutsu far excels them all in its way of Attaining Ojo. Now there are some people who are unacquainted with the way of birth into the Pure Land, who say, that because the Nembutsu is so easy, it is all right for those who are incapable of keeping up the practices required in the Shingon, and the meditation of the Tendai sects, but such a cavil is absurd. What I mean is, that I throw aside those practices not included in Amida's Vow, nor prescribed by Shakyamuni, nor having the endorsement of the Buddhas of all quarters of the universe, and now only throw myself upon the Original Vow of Amida, according to the authoritative teaching of Shakyamuni, and in harmony with what the many Buddhas of the six quarters have definitely approved.

I give up my own foolish plans of salvation, and devote myself exclusively to the practice of that mightily effective discipline of the Nembutsu, with earnest prayer for birth into the Pure Land. This is the reason why the abbot of the Eshin-in Temple in his work Essentials of Salvation (Ojoyoshu) makes the Nembutsu the most fundamental of all. And so you should now cease from all other religious practices, apply yourself to the Nembutsu alone, and in this it is all-important to do it with undivided attention. Zendo,3 who himself attained to that perfect insight (samadhi) which apprehends the truth, dearly expounds the full meaning of this in his Commentary on the Meditation Sutra, and in the Two-volumed Sutra the Buddha (Shakya) says, 'Give yourself with undivided mind to the repetition of the name of the Buddha who is in Himself endless life.' And by 'undivided mind' he means to present a contrast to a mind which is broken up into two or three sections, each pursuing its own separate object, and to exhort to the laying aside of everything but this one thing only. In the prayers which you offer for your loved ones, you will find that the Nembutsu is the one most conducive to happiness. In the Essentials of Salvation, it says that the Nembutsu is superior to all other works. Also Dengyo Daishi, when telling how to put an end to the misfortunes which result from the seven evils, exhorts to the practice of the Nembutsu. Is there indeed anything anywhere that is superior to it for bringing happiness in the present or the future life? You ought by all means to give yourself up to it alone.'

Shinran — 'The Nembutsu Alone is True'

The following excerpt — 'The Nembutsu Alone is True' — is from a collection of Shinran's sayings, said to have been made by his disciple Yuiembo, who was concerned over heresies and schisms developing among Shinran's followers and wished to compile a definitive statement of his master's beliefs. In this text Shinran is said to have said: Your aim in coming here, travelling at the risk of your lives through more than ten provinces, was simply to learn the way of rebirth in the Pure Land. Yet you would be mistaken if you thought I knew of some way to obtain rebirth other than by saying the Nembutsu, or if you thought I had some special knowledge of religious texts not open to others. Should this be your belief, it is better for you to go to Nara or Mt. Hiei, for there you will find many scholars learned in Buddhism and from them you can get detailed instruction in the essential means of obtaining rebirth in the Pure Land. As far as I, Shinran, am concerned, it is only because the worthy Honen taught me so that I believe salvation comes from Amida by saying the Nembutsu. Whether the Nembutsu brings rebirth in the Pure Land or leads one to Hell, I myself have no way of knowing. But even if I had been misled by Honen and went to Hell for saying the Nembutsu, I would have no regrets. If I were capable of attaining Buddhahood on my own through the practice of some other discipline, and yet went down to Hell for saying the Nembutsu, then I might regret having been misled. But since I am incapable of practicing such disciplines, there can be no doubt that I would be doomed to Hell anyway. [Source: 'The Nembutsu Alone Is True', 'Tannisho,' selections, "From Primitives to Zen": Shinran, Translation in Wm. Theodore de Bary (ed.), “Sources of Japanese Tradition” (Columbia University Press, 1958), pp. 216-18, at Eliade Page webiste ]

If the Original Vow of Amida is true, the teaching of Shakyamuni cannot be false. If the teaching of the Buddha is true, Zendo's commentary on the Meditation Sutra cannot be wrong. And if Zendo is right, what Honen says cannot be wrong. So if Honen is right, what 1, Shinran, have to say may not be empty talk.

Such, in short, is my humble faith. Beyond this I can only say that, whether you are to accept this faith in the Nembutsu or reject it, the choice is for each of you to make. . . . If even a good man can be. reborn in the Pure Land, how much more so a wicked man.'

People generally think, however, that if even a wicked man can be reborn in the Pure Land, how much more so a good man! This latter view may at first sight seem reasonable, but it is not in accord with the purpose of the Original Vow, with faith in the Power of Another. The reason for this is that he who, relying on his own power, undertakes to perform meritorious deeds, has no intention of relying on the Power of Another and is not the object of the Original Vow of Amida. Should he, however, abandon his reliance on his own power and put his trust in the Power of Another, he can be born in the True Land of Recompense. We who are caught in the net of our own passions cannot free ourselves from bondage to birth and death, no matter what kind of austerities or good deeds we try to perform. Seeing this and pitying our condition, Amida made his Vow with the intention of bringing wicked men to Buddhahood. Therefore the wicked man who depends on the Power of Another is the prime object of salvation. This is the reason why Shinran said, 'If even a good man can be reborn in the Pure Land, how much more so a wicked man!' . . .

It is regrettable that among the followers of the Nembutsu there are some who quarrel, saying 'These are my disciples, those are not.' There is no one whom I, Shinran, can call my own disciple. The reason is that, if a man by his own efforts persuaded others to say the Nembutsu, he might call them his disciples, but it is most presumptuous to call those 'my disciples' who say the Nembutsu because they have been moved by the grace of Amida. If it is his karma to follow a teacher, a man will follow him; if it is his karma to forsake a teacher, a man will forsake him. It is quite wrong to say that the man who leaves one teacher to join another will not be saved by saying the Nembutsu. To claim as one's own and attempt to take back that faith which is truly the gift of Amida-such a view is wholly mistaken. In the normal course of things a person will spontaneously recognize both what he owes to the grace of Amida and what he owes to his teacher [without the teacher having to assert any claims]. . . .

The Master was wont to say, 'When I ponder over the Vow which Amida made after meditating for five kalpas, it seems as if the Vow were made for my salvation alone. How grateful I am to Amida, who thought to provide for the salvation of one so helplessly lost in sin!' When I now reflect upon this saying of the Master, I find that it is fully in accordance with the golden words of Zendo. 'We must realize that each of us is an ordinary mortal, immersed in sin and crime, subject to birth and death, ceaselessly migrating from all eternity and ever sinking deeper into Hell, without any means of delivering ourselves from it.'

It was on this account that Shinran most graciously used himself as an example, in order to make us realize how lost every single one of us is and how we fail to appreciate our personal indebtedness to the grace of Amida. In truth, none of us mentions the great love of Amida, but we continually talk about what is good and what is bad. Shinran said, however, 'Of good and evil I am totally ignorant. If I understood good as Buddha understands it, then I could say I knew what was good. If I understood evil as Buddha understands it, then I could say I knew what was bad. But I am an ordinary mortal, full of passion and desire, living in this transient world like the dweller in a house on fire. Every judgment of mine, whatever I say, is nonsense and gibberish. The Nembutsu alone is true.'

Shinran's “Lamentation and Self-Reflection”

Sinran's most significant treatise is the "Kyōgyōshinshō" (Teaching Practice, Faith, and Realization).” [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]In “Lamentation and Self-Reflection,” Shinran wrote :

Although I have entered the Pure Land path,

I remain incapable of true and genuine thoughts and feelings.

My very existence is pervaded by vanity and falsehood;

There is nothing at all of any purity of mind.

Being unrepentant and lacking in shame,

I have no mind of truth and sincerity.

And yet, because the Name has been given by Amida Buddha,

The universe is suffused with its virtues.

Deeply saddening is it that in these times

Both the monks and laity in Japan,

While seeking to conform with Buddhist manner and deportment,

Worship gods and spirits of the heavens and earth.

[Source: “Sources of Japanese Tradition”, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, and Paul Varley, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 226-227]

Pure Land Buddhism Issues

According to the BBC: Is this a new understanding of Buddhism? On the surface Pure Land Buddhism seems to have moved a very long way from the basic Buddhist ideas, and it's important to see how it might actually fit in. The way to do this is to tackle each issue and see what's really going on. [Source: BBC]

Amida Buddha is treated as if he were God: On the surface, yes. But perhaps chanting Amitabha Buddha's name is not praying to an external deity, but really a way of calling out one's own essential Buddha nature. However some of Shinran's writings do speak of Amitabha Buddha in language that a westerner would regard as describing God.

“The Pure Land appears to be a supernatural place: On the surface, yes. But perhaps the Pure Land is really a poetic metaphor for a higher state of consciousness. Chanting the name can then be seen as a meditative practice that enables the follower to alter their state of mind. (This argument is quite hard to sustain in the face of the importance given to chanting the name in faith at the moment of death - when some supernatural event is clearly expected by most followers. And the chanting is not regarded solely as a meditative practice by most followers. However gaps between populist and sophisticated understanding of religious concepts are common in all faiths.)

There is no reliance on the self to achieve enlightenment: On the surface, yes. But in fact this is just a further move in the direction that Mahayana Buddhism has already taken to allow assistance in the journey to liberation. And the being still has much work to do when they arrive in the Pure Land. (Shinran however taught that arriving in the Pure Land was actually the final liberation - the Pure Land was nirvana.)

Hiraizumi Temples

Hiraizumi Temples, Gardens and Archaeological Sites of the Pure Land Buddhist school was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011. According to UNESCO: “Hiraizumi – Temples, Gardens and Archaeological Sites Representing the Buddhist Pure Land comprises five sites, including the sacred Mount Kinkeisan. It features vestiges of government offices dating from the 11th and 12th centuries when Hiraizumi was the administrative centre of the northern realm of Japan and rivalled Kyoto. The realm was based on the cosmology of Pure Land Buddhism, which spread to Japan in the 8th century. It represented the pure land of Buddha that people aspire to after death, as well as peace of mind in this life. In combination with indigenous Japanese nature worship and Shintoism, Pure Land Buddhism developed a concept of planning and garden design that was unique to Japan.

“The four temple complexes of this once great centre with their Pure Land gardens, a notable surviving 12th century temple, and their relationship with the sacred Mount Kinkeisan are an exceptional group that reflect the wealth and power of Hiraizumi, and a unique concept of planning and garden design that influenced gardens and temples in other cities in Japan....The Pure Land Gardens of Hiraizumi clearly reflect the diffusion of Buddhism over south-east Asia and the specific and unique fusion of Buddhism with Japan's indigenous ethos of nature worship and ideas of Amida's Pure Land of Utmost Bliss. The remains of the complex of temples and gardens in Hiraizumi are symbolic manifestations of the Buddhist Pure Land on this earth.

See Separate Article: NEAR SENDAI: HIRAIZUMI, MATSUSHIMA ISLANDS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: 1) 1st Daruma, British Museum, 2) 2nd daruma, Onmark Productions, 3) Koyasan and diagrams JNTO 4) Monks, Ray Kinnane, 5) 19th century monks and hermit 6) Visualizing Culture, MIT Education 7) calligraphy, painting, Tokyo National Museum.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024