JAPANESE GARDENS

No Japanese house, palace or temple is considered complete without a garden. Japanese gardens, however, have little in common with the grand, geometric, gardens of Rome, the Moghal empire in India, France and England, nor are they similar to modern Western gardens with their neat hedges, careful patterns and colorful flowers that bloom on a rotating basis.

Instead Japanese gardens feature moss-covered dirt and rocks, paths that never seem to follow a straight line, rocks that have special significance and a layout plane that harmonizes with the natural surroundings that sometimes embraces mountains 10 or so kilometers in the distance. The Japanese love flowers. They favor locally grown flowers. Chrysanthemums, carnations, roses and orchids are popular imports. But they are not necessarily associated with traditional Japanese gardens.

Dave Carpenter of Associated Press wrote: Japanese gardens are about inspiring and soothing the soul. And you don't have to be a gardening expert or Zen Buddhist to appreciate all they have to offer — the beauty, the tranquility, even the Zen. Reflecting a design that originated in 12th-century Japan, a typical Kamakura period garden contains a large pond, a five-story waterfall, a granite pagoda, curving bridges over boulder-strewn streams, and well-manicured plants and trees leaning toward the water. A traditional Japanese guesthouse, tea house and gazebo are built by a traditional craftsman using just files, chisels and hammers. [Source: Dave Carpenter, Associated Press, July 26, 2011]

The designer Hoichi Kurisu said the primary of his garden was to “to make people feel peaceful, forever calm, energized.” He also said anyone “strolling through” his garden’s “pine forest of bamboo grove” would find a refuge where it was possible to “lay aside the chaos of the troubled world.” [Source: Smithsonian magazine, May 2011]

Many traditional gardens are being lost to urban expansion and bulldozed over to make room for apartments, parking lots and offices. There are also few master gardeners left in Japan and few young people want to take the time to master the art form. "Traditional gardens are disappearing," Master gardener Shinzo Arai, who teaches seven apprentices, told TIME, "because of the high cost of land and because a generation of Japanese who love gardens is dying out...It requires years to train and pass on techniques and teachings. I don't have many years left, so this is my last group."

Good Garden Websites and Sources: Good Photos of Gardens at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; About Japanese Gardens aboutjapanesegardens.org ; The Japanese Garden by Bowdoin College bowdoin.edu/japanesegardens ; Japanese Garden Database jgarden.org ; Japanese Garden Forum forums.gardenweb.com/forums/jgard/ ; History of Japanese Garden tigersheds.com/garden-resources ; Types of Gardens mcel.pacificu.edu ; Photo Gallery of Zen Gardens in Kyoto /phototravels.net/japan/photo-gallery/japanese-rock-gardens ; Japan Garden Society gardening.or.jp ; Book: “ Reading Zen in the Rocks: the Japanese Landscape Garden” by Francois Berthier (University of Chicago Press, 2000).

Bonsai The Bonsai Site bonsaisite.com ; Bonsai Guide Book in Japan wafu.com ; Bonsai Empire bonsaiempire.com ; Bonsai Clubs International bonsai-bci.com ; Shohin Bonsai World shohin-bonsai.org ; Ho Yuku Bonsai hoyoku.com ; Mini-Bonsai mini-bonsai.com ; Ryuen and Gekko ; Bonsai Network Japan j-bonsai.com ; Omiya Bonsai Village (near Tokyo) Bonsai in Japan /members.iinet.net.au

Gardens in Japan Japan Guide List of Gardens Japan Guide ; Gardens in Japan Garden Visit ; Kenrokuen Garden (central Kanazawa) is regarded as one of the three most beautiful gardens in Japan, along with Kairakuen in Mito and Korakuen in Okayama. Websites: Kanazawa Tourism site kanazawa-tourism.com ; Photos of Kenrokuen dsphotographic.com ; Korakuen Gardens (in Okayama) Japan Guide japan-guide ; Photos Reggie.net ; Adachi Museum in Yasugi Shimane features has gardens that have been named the No. 1 in Japan for four consecutive years by the U.S. publication the Journal of Japanese Gardening. No.2 is Kyoto’s famous Katsura Rikyu. Adachi Museum site adachi-museum.or.jp and adachi-museum.or.jp

Gardens in Kyoto Kyoto Gardens.org kyotogardens.org ; Ryoanji Temple and Zen Garden ryoanji.jp ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; UNESCO World Heritage site: UNESCO website; Japan Guide japan-guide.com ; Saiho-ji Temple Moss Garden: Welcome to Kyoto pref.kyoto.jp ; Photos phototravels.net . Katsura Imperial Villa: Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Imperial Household Agency sankan.kunaicho.go.jp ; Tour of Katsura Rikyu katsura-rikyu.50webs.com Katsura Rikyu ranked No. 2 as the best garden in Japan by the U.S. publication the “Journal of Japanese Gardening” . Tokyo Area Gardens Japan Guide japan-guide.com ; Japanese Lifestyle japaneselifestyle.com.au ; Kairakuen Gardens (in Mito) Japan Guide japan-guide.com ; Photos Reggie.net

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TEA CEREMONY AND FLOWER ARRANGING IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GARDENS AND BONSAI IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; RECREATION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

Types of Japanese Gardens

The classic Japanese garden is an artificial garden that reproduces natural scenic beauty in a heightened intensity. Its charm lies in its subtle, highly sophisticated layout in a limited space.The aim of Japanese landscape gardening, which has a long history of development, is to create a scenic composition by arranging rocks, trees, shrubs and running water in such a way as to create the sweep of a vast landscape. [Source: JNTO]

Japanese gardens are usually referred to as the “hill garden” (“tsukiyama”) and the “waterless stream garden” (“karesansui”) The hill garden features a hill usually combined with a pond and a stream. It can be viewed from various vantage points, as you stroll along the paths, or appreciate it from within a house to which it is attached. Fine specimens of this style are the gardens of Tenryuji Temple and Saihoji Temple, both in Kyoto. In the dry landscape garden, rocks and sands form the main elements, the sea being symbolized not by water but by a layer of sand with furrows suggestive of the rippling movement, and waterfalls by an arrangement of rocks. Examples of this style are the gardens of Ryoanji Temple and Daitokuji Temple, also in Kyoto.

With the introduction of the tea ceremony in the 14th century, the chaniwa (garden attached to the tea-ceremony house) came to be designed and laid out. Actually, it is not a garden but a narrow path leading up to the chashitsu (tearoom proper) The aim of the designer of this style was to create a feeling of solitude and detachment from the world. A tea garden is mainly featured by the placement of stepping stones. Most of the tea gardens are not open to the public.

Characteristics of Japanese Gardens

Three essential elements of Japanese gardening are: 1) the permanence of stone; 2) plants for texture and color; and 3) the soothing, reflective qualities of water. Small touches in nooks and crannies are also important. There including things like a bamboo "deer chaser" fountain in the woods that periodically makes a knocking sound as it hits a rock; the coin basin; the detailed craftsmanship in the gazebo by the waterfall. "There's a lot of little detail," says the owner of one Japanese garden. "If you fly through, you miss it."

In addition to trees and shrubs, the Japanese garden makes artistic use of rocks, sand, artificial hills, ponds, and flowing water. In contrast to the geometrically arranged trees and rocks of a Western-style garden, the Japanese garden traditionally creates a scenic composition that, as artlessly as possible, mimics nature. Garden designers followed three basic principles when composing scenes. They are reduced scale, symbolization, and “borrowed views.” The first refers to the miniaturization of natural views of mountains and rivers so as to reunite them in a confined area. This could mean the creation of idealized scenes of a mountain village, even within a city. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Symbolization involves abstraction, an example being the use of white sand to suggest the sea. Designers “borrowed views” when they used background views that were outside and beyond the garden, such as a mountain or the ocean, and had them become an integral part of the scenic composition. The basic framework of the Japanese garden, according to one school of thought, is provided by rocks and the way they are grouped. Ancient Japanese believed that a place surrounded by rocks was inhabited by gods, thus naming it “ amatsu iwasaka “(heavenly barrier) or “ amatsu iwakura “(heavenly seat). Likewise, a dense cluster of the trees was called “ himorogi “(divine hedge); moats and streams, thought to enclose sacred ground, were referred to as “ mizugaki “(water fences).

“Japanese gardens can be classified into two general types: the “ tsukiyama “(hill garden), which is composed of hills and ponds, and the “ hiraniwa “(flat garden), a flat area without hills and ponds. At first, it was common to employ the hill style for the main garden of a mansion and the flat style for limited spaces. The latter type, however, became more popular with the introduction of the tea ceremony and the “ chashitsu “(tea-ceremony room).

Japanese Gardens as Miniature Landscapes

In Japan, space, or lack of it, is always a consideration, and as a consequence gardens are often viewed as miniaturized landscapes in a small yard, balcony or window box that are intended to evoke something larger. One reason why bonsai (the art of dwarfing trees) is so popular in Japan is that sometimes so space is so tight that gardens have to be brought indoors.

Japanese gardens are designed to respond to all the seasons and be a microcosm of nature. "Mountains, oceans, islands, and waterfalls are all there in small horizontal compass," wrote historian Daniel Boorstin. "Rocks, a prominent foil to the fragility of growing trees and shrubs and mosses, affirm the unchanging. They are not the architects' effort to defy the forces of time and nature, but another way of acquiescing. The Japanese garden renews what dies or goes dormant, and reveres what survives." [Source: Daniel Boorstin, "The Creators"]

Suizenji Park in Kumamoto is one of the finest example of a Japanese garden with miniature landscapes. Established in 1632, it contains imitations the 53 stations of the old Tokaido Road (between Kyoto and Tokyo) complete with miniature models of Mt. Fuji, Lake Biwa and other famous places along the route.

History of Japanese Gardening

The earliest known gardens date back to the Asuka period (593-710) and the Nara period (710-794). In the Yamato area (now in Nara Prefecture), designers of imperial family gardens and those of powerful clans created imitations of ocean scenes that featured large ponds dotted with islands and skirted by “seashores.” It was at this time that Buddhism was brought to Japan from the continent by way of the Korean peninsula. Immigrants from there added continental influences to Japanese gardens, such as stone fountains and bridges of Chinese origin. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Christal Whelan wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “The Nihon Shoki describes how the 33rd emperor of Japan — Empress Suiko (A.D. 554-628) — employed Korean artisans to build a garden that would feature a miniature version of the island-mountain Sumeru of Buddhist cosmology. While the Empress' commission surely expressed her exemplary faith, a type of garden known as the "Pure Land Garden" later became fashionable during the Heian period. Through a technique known as shukkei or "contracted scenery," gardens were crafted to replicate actual or imagined landscapes. In the case of Pure Land Gardens, a scene glimpsed through a description in a sutra or a painting might serve as a template.”

“Ancient gardens of the Asuka and Nara periods — which often employed shukkei — were even called shima (island) rather than niwa (garden) for their preference to represent seascapes and island scenery. Such windswept islands and rocky beaches were later canonized in the Edo period through the work of Confucian scholar Hayashi Junsai, who traveled the entire Japanese archipelago appraising its scenery. His assessment crystalized into tradition. These sankei or "three most spectacular scenic spots" in Japan “Matsushima, Miyajima and Amanohashidate — all depict various kinds of islands, from pine-clad islets to sandbars immortalized over the centuries in poems, paintings, and certainly incorporated into the grammar of gardens.

Japanese gardening developed into a unique art form during the Heian Period (794-1185), when the Imperial Japanese court spent much pursing the arts and social pleasures. Heian gardens featured imitations of scenery and were set harmoniously among wooden building. Many Japanese gardens are still built to the specifications of the Sakuteiki, an 11th century book regarded as the world' oldest garden manual.

Heian Period Gardens

The capital of the Japanese state was moved from Nara to Kyoto in 794, and the Heian period (794-1185) began. As the noble family of Fujiwara consolidated its grip on power, an aristocratic, natively inspired art and culture developed. These aristocrats lived in luxurious mansions built in the “ shinden-zukuri “style. The gardens of this age were also magnificent. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Several rivers came together in Kyoto, and channels were dug to let water flow through various parts of the city. Summers in Kyoto are hot and humid, so people fashioned ponds and waterfalls in order to bring a sense of coolness. Streams called “ yarimizu “were made to flow between buildings and through the gardens of mansions. In this “ funa asobi “(pleasure boat) style, the often oval-shaped ponds were large enough to allow boating; and fishing was made convenient by putting up fishing pavilions that projected out over the water and were connected by covered corridors to the mansion’s other structures. Between the main buildings and the pond was an extensive area covered with white sand, a picturesque site for the holding of formal ceremonies.

“Another style of garden, the “ shuyu “(stroll) style, had a path that allowed strollers to proceed from one vantage point to another, enjoying a different view from each one. Such gardens were frequently found in temples and grand houses in the Heian, Kamakura, and Muromachi periods. The garden of the Saihoji temple in Kyoto, laid out by the priest Muso Soseki in the Muromachi period, is well known as a typical “stroll” garden. It is designed to give the impression that the pond blends naturally with the mountain in the background.

Zen and Jodo-Style Gardens

In the tenth century Japan’s aristocracy became increasingly devout in its practice of Buddhism. As faith in the concept of a paradise known as Jodo (Pure Land) spread, the garden came to be modeled on images of Jodo as described in scripture and religious tracts. It represented a crystallization of some extremely ancient Japanese garden motifs. In this type of garden, the focal point is the pond, with an arched bridge reaching to a central island. The garden of the Byodoin, a temple at Uji (near Kyoto), is a good example of Jodo-style garden. This temple was originally the country home of a powerful man of the time, Fujiwara no Michinaga. Because elite members of society took great interest in gardens, they are the subject of numerous excellent critical works, the oldest being “ Sakuteiki “(Treatise on Garden Making), by Tachibana no Toshitsuna (1028-1094). [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The Kamakura period (ca. 1185-1333) that followed saw the rise of a warrior class and the influence of Zen priests from China, bringing about changes in the style of residential buildings and gardens. It was not the custom of the military elite to hold splendid ceremonies in their gardens. Instead, they preferred to enjoy their gardens from inside the house, and gardens were designed to be appreciated primarily for their visual appeal. In this period, priest-designers, or “ ishitateso “(literally, rock-placing monks), came to the fore. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Zen gardeners during the Muromachi period (1333-1568) developed a new style of gardening in which nature was stripped down to its essence and the vastness of nature was presented in a symbolic manner with a limited number of trees and rocks. "Zen provided a solid philosophical base for designers," Reiji Ito, an authority on Japanese gardens told TIME. "The idea is there is a universe in the smallest space."

“It is said that the golden age of Japanese gardens occurred in the Muromachi period (1333-1568). Groups of skilled craftsmen called “ senzui kawaramono “(mountain, stream, and riverbed people) were responsible for creating a new style of garden, known as “ karesansui “(dry mountain stream). Heavily influenced by Zen Buddhism, these gardens are characterized by extreme abstraction: groups of rocks represent mountains or waterfalls, and white sand is used to replace flowing water. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“This form of garden, not seen in any other part of the world, was probably influenced by Chinese ink-painted landscapes of barren mountains and dry riverbeds. Examples include the rock gardens at the temples of Ryoanji and Daitokuji, both in Kyoto. The former, created with just 15 rocks and white sand on a flat piece of ground, is also typical of flat-style gardens. In addition, gardens of this period received much influence from the style of architecture known as “ shoin-zukuri”, which included the “tokonoma“ (alcove), “ chigaidana “(staggered shelves), and “ fusuma “(paper sliding doors), and still serves as the prototype for today’s traditional-style Japanese house. In this “ kansho “or “ zakan “(contemplation) style, the viewer is situated in a “ shoin”, a room in a “ shoin-zukuri “building, and the view is composed so as to resemble a picture that, like a fine painting, invites careful and extended viewing.

Many Japanese gardens are modeled after specific places like Mt. Fuji or the Inland Sea. Known as “shakkei” ("borrowed view"), this notion is commonly expressed in miniature recreations of the symmetrical design of Kyoto and the misty mountains that surround it. In feudal times, there was a daimyo who wanted to go to China but couldn't, so he built a replica of China in his garden.

Kaiyu-Style Gardens of the Edo period (1603-1868)

The various forms that gardens took on over the centuries were synthesized in the Edo period (1603-1868) in “ kaiyu “(many-pleasure) gardens, which were created for feudal lords. Superb stones and trees were used to create miniature reproductions of famous scenes. People walked from one small garden to another, appreciating the ponds in the center. The garden of the Katsura Detached Palace in Kyoto, a creation of the early Edo period, is a typical “ kaiyu”-style garden, with a pond in the center and several teahouses surrounding it. This garden came to the attention of a wide audience through the writings of German architect Bruno Taut. Another famous garden in Kyoto is the Kyoto Imperial Palace Garden. Constructed in the seventeenth century, it is called Oikeniwa, which means “Pond Garden.” A large pond dotted with several pine-clad islets occupies most of the garden. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“The Korakuen Garden, laid out in 1626, is one of the most magnificent “ kaiyu”-style gardens in Tokyo. The lake in the garden has an island with a small temple dedicated to Benzaiten, originally an Indian goddess known in Japan as one of the Seven Deities of Good Luck. The stone bridge to the island is called the Full-Moon Bridge because of its half-circle shape. The reflection of the bridge on the water completes a circle. The Hama Detached Palace Garden is another famous “ kaiyu “garden in Tokyo. The most celebrated view of the garden, which was constructed in the Edo period, is of a lovely tidal pond spanned by three bridges. Each bridge is shaded by wisteria-vine trellises and leads to an islet. The layout of the ponds, lawns, and riding grounds creates the atmosphere of a villa maintained by a feudal lord in the Edo period. The so-called three most beautiful landscape gardens in Japan — Kairakuen at Mito, Ibaraki Prefecture; Kenrokuen at Kanazawa, Ishikawa Prefecture; and Korakuen at Okayama, Okayama Prefecture — are also of this type. Beginning in the Meiji period (1868-1912), the influence of the West began to extend even to traditional Japanese garden design, such as incorporating large-scale spaces with extensive lawns. Tokyo’s Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden is one example.

Some gardens are conceived with poetry in mind. The garden at Rikugien, an 18th century estate in Tokyo, was designed with 88 views inspired by lines of classic poetry and visitors to the garden are expected to guess the lines that each view represents. Other gardens are built to be observed through a window from a room inside a house, with the view complimenting the paintings and other art objects in the room. [Source: Bruce Coats, National Geographic, November 1989]

There are four main types of gardens: 1) pleasure boat style (“funa asobi”), built around a large pond, which offers the best views; 2) stroll style (“shuyu”), which is designed to be enjoyed while walking on a path, with unique views opening up on the same garden from different points along the path; 3) contemplative style (“kansho”), designed to be enjoyed from one place; and 4) many pleasure style (“kaiyu”). Many pleasure style gardens usually feature many small gardens organized around a central pond. There is often a small tea house and paths that lead to a variety of view of changing miniature landscapes.

The tea garden, imbued with a quiet spirituality, was developed in conjunction with the tea ceremony, as taught by Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591). It was through the tea garden, which avoided artificiality and was created so as to retain a highly natural appearance, that one approached the teahouse. Today’s Japanese garden incorporates a number of elements inherited from the tea garden, such as stepping stones, stone lanterns, and clusters of trees. The simply designed gazebos in which guests are served tea also have their origin in the tea garden. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Japanese Rock Gardens

Rock gardens are one the most unique forms of Japanese gardening and perhaps the hardest for Westerners to understand. Usually composed of rocks placed among raked gravel, they are regarded as a kind of contemplative style garden and sometimes called dry mountain stream (“kare kansho”) gardens.

Stone quality is judged in terms of shape, color, texture and original location of the rock. The best stones have wabi, a Zen term that means inner life and suggest beauty in its most simple and austere form. Placements of the stones is often based on notions of shakkei. Years are sometimes spent finding the right position for a rock and top quality garden rocks have been sold for as much as $370,000. Rock gardens are sometimes put in bathrooms.

One central idea to a rock garden is that a rock can be moved but not altered. An upright rock, for example, is never laid on its size. Rocks are carefully chosen for their aesthetic qualities, such a shape and how light is cast upon them. The size, color, perspective, vanishing point and even the presence of lichen and moss are all considered.

The Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi said,”In Japan, the rocks in the garden are so planted to suggest a protuberance from the primordial mass below. Every rock gains enormous weight, and that is why the whole garden may be said to be a sculpture, whose roots are joined way below.”

Ryoanji Garden at Ryoanji Temple) in Kyoto is one of the most famous gardens in Japan and most exquisite example of the dry landscape-style garden. Consisting of 15 rocks of various sizes, well placed on a carefully-raked bed of white gravel, this small garden was created sometime between 1499 and 1507 by Zen monks and measures 256 square meters. There are no trees or shrubs. the only green is from moss that grows on some of the rocks. One scholar described it as "a beautiful poem, a simple statuary, a deep philosophy, a wonderful picture...and a profound religion."

The 15 rocks and white gravel are supposed to imitate water. From nowhere except the temple can the rocks all be seen at once. The rocks are divided into five groups of two, three or five. Each group can be regarded as the cardinal directions and the center, which some interpret as representing existence and the universe But reading to much meaning into the garden defies the Zen aesthetic of simplicity and austerity. Many believe the stones represent a range of mountains or a coastal scene or a dry waterfall. The creators of the garden are not known. Two names are carved on of the rocks but its is not known whether the are names of designers, laborers or ancient tourists. It is a good idea to go early to this garden if you want to contemplate its simple beauty without being engulfed by school groups.

Garden Care and Trends in Japan

Proper care of a garden is considered so important that some gardens have full time "river washers," whose duty is sweeping the ponds and streams. During the winter sometimes pruned trees are supported with rope webs, fragile flowering shrubs are protected by straw huts and palms are cloaked with special straw "snow jackets" to protect them from the snow and cold.

Straw mats are wrapped around the trees in the early winter, During the winter the insects multiply in the warm mats, which are removed in the early spring and burned, killing the insects inside. One study found that the straw mats used to wrap pine trees do more harm than good: mostly trapping insects that are beneficial to the tree.

Many Japanese are turning away from traditional Japanese gardening and taking up English-style gardening, with pansies and primroses, because English gardens are easier to maintain, cheaper, require less work and are regarded as more cheerful. One gardener told the Los Angeles Times, "I love Japanese gardens, but you put in natural stones, and they're so heavy you can't put them in yourself, you have to hire a gardener to do it. Then it takes decades to get the moss on the stones just right...I love Japanese culture and think it is very beautiful. But in ordinary daily life, it is becoming more and more distant."

Nevertheless, gardening remains very popular. In 1997, Japan's 38 million gardeners spent $5.7 billion on their hobby (a 35 percent increase from 1988).

Some of the most impressive gardens in Tokyo are found on the rooftops of modern buildings such as those in Roppongi Hills. In recent years rooftop gardens have been promoted as way to reduce carbon dioxide emissions and reduce the heat island effect. One experiment found that the temperatures on rooftops of building in in summer dropped from 50 degree C to 30 degrees C with additions of trees, plants and flowers. The plants also reduced the heat of the outer walls of building reducing the heart island effect.

In 2001, a law was passed that all buildings of a certain size were required to have rooftop garden. There are now about 100 hectares (150 soccer fields) of such gardens in Tokyo today. From a helicopter looks like a mass black and gray asphalt and concrete with the exception of a few parks and rooftop gardens.

Japanese Gardening Tips

Time Gruner, the curator of a Japanese garden in the United States offered these tips to help create the feel of a Japanese garden: 1) PRUNE HEAVILY. Pruning keeps plants in proper scale for their space. It also makes your garden more interesting if you can see through to the other side. Prune in a way that creates a sense of mystery — a little added texture and depth. LEAN YOUR PLANTS. Lean plants in to a focal point, whether it's a waterfall or your front door. Plants leaning in toward the sidewalk make for an inviting, comforting feeling. 3) INCORPORATE WATER FEATURES. The sound of running water creates interest in a garden. It also attracts frogs, dragonflies, and birds bathing and preening. [Source: Dave Carpenter, Associated Press, July 26, 2011]

Gruner also advises: 1) USE BIG ROCKS. Go with the biggest rocks you can afford, handle and move. "You don't have to have boulders, they're just really great," says Gruner. You can also use rocks to change the flow if you have a water feature. 2) THINK CHARACTER AND COLOR. Restrained use of unusual plants and trees, or those of contrasting color, will enhance a garden. One good option is dwarf white pines, which have great character, few disease problems and grow in small spaces. 3 APPLY WHIMSY CAREFULLY. Whimsical features such as wind chimes, stone frogs or humorous sculptures can spice up a garden, but don't overdo it. If the oddities play off nature (no gnomes, please) and are carefully integrated, whimsy can work.

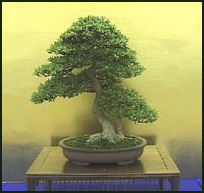

Bonsai

Bonsai, which literally means "tree in a tray," is the art of creating aesthetically-pleasing miniature trees. First practiced in China around A.D. 200 and deeply influenced by Zen Buddhism, bonsai was introduced to Japan from China in the 13th century by a Buddhist monks skilled at growing miniature trees in containers. [Source: Ogden Tanner, Smithsonian magazine]

Bonsai (pronounced bone-SIGH) was one of several methods used by Buddhist monks to help them achieve enlightenment through disciplined intercourse with nature. The Japanese turned this skill into an art form in which gardeners produced miniature trees that looked as if they shaped and twisted by storms, toughened by fierce sun light and gnarled by mountains winds. As is true with other Zen art forms, the objective of bonsai is not to produce something that is decorative but rather to make something that is austere and simple and invites meditation.

In Japan, there are numerous bonsai trees between 100 and 200 years old and a few that are five hundred years old. These trees are passed down from generation to generation as if they were priceless paintings. Softball-size, 50-year-old bonsai maple trees are worth around $5,000, and first-rate seven-foot bonsai pine trees sell for as much as $35,000. Ancient trees have periodically sold for $200,000 and some have been sold at auctions for more than $1 million.

Art and Care of Bonsai

In Japan, bonsai has traditionally been an art practiced by men while ikebana (flower arranging) has been the domain of women. Tree species favored for bonsai include Japanese white pine, juniper and Japanese cedars because they live a long time and grow slowly. Japanese maples, apricot-plum trees, ginkgo trees, cherry trees, Chinese quince and zelkovas are also popular. Almost all of these trees have to be grown outside and are brought inside for one or two days at a time to be admired.

The objective of a bonsai grower is to produce a perfect tree in miniature, that looks beautiful in all the seasons, through patience, skill and tenderness. The growth of the tree is stunted by placing it in a tray with a depth one or two times the diameter of the trunk. Various shapes are achieved by pruning and wiring branches to dramatizes the lines, adding weight to reshape the branches, and pinching off the leaves for years until they are the same scale as the tree.

Proportion, perspective, color balance, character, freshness, creativity and emotion are all things that bonsai artists take into consideration. Good bonsai trees should be free of excess branches; have foliage grouped into dense clusters; have a gnarled, weathered-looking trunk; and have breaks in the foliage to see the trunk and, as the Japanese say "spaces for birds to fly through." One bonsai grower told Smithsonian magazine, "it takes at least three generations to make a really good bonsai."

Bonsai tree also require routine and careful pruning with bonsai scissors and pruning pincers, daily watering and inspections, and occasional fertilizing and repotting. In Japan, there are bonsai nurseries that offer "boarding and grooming" for vacationing bonsai growers.

One Japanese bonsai artist told the Daily Yomiuri, "Cutting the leaves and branches stimulates new growth and allows new elements to the trees. trimming the roots, repotting and fertilizing, encourages the growth of new roots. Trees in a natural environment don’t have this benefit and may die, while bonsai remain healthy.

Large sections of the trunk and branches of older trees are deadwood that is intertwined with the living tree. The deadwood is often preserved with a lime-sulfur solution that keeps it from rotting and prevents rot from spreading to the living tree. .

Types of Bonsai

The are five main styles of bonsai: 1) formal upright; 2) curved trunk (the most common); 3) slanting; 4) cascade; and 5) “literati”, with a slender trunk and fewer branches. Within these classifications are bonsai that stress the windswept, twisted look; that are grown in rocks; and that are grouped in "forests" of up to 30 plants.

Most bonsai are between one and four feet tall. “Shohin” are a style of mini-bonsai with plants less than six inches high. Even smaller are “shito”, three-inch-high bonsai grown in a thimble-size pots with a teaspoon of soil. “Suseki” ("viewing stones") is a kind of bonsai with no trees at all, only aesthetically-pleasing rocks. For further variation, bonsai trays are of often augmented with mosses, rocks, grasses, sand, ferns and other plants. “Bonkei” is a related art in which scenes from nature are created in a small tray using moss, clay sand and other materials.

Mini-bonsai in pots ranging from the size of thimbles to tea cups became popular in the early 2000s. The plants are kept in small spaces and require relatively little care. Going hand and hand with this is “mambonsai”, the art of making miniature landscapes tiny figurines placed in the moss.

Image Sources: 1) 2) amolife, 3) 7) 8) JNTO 4) and 6) Japan Zone 6) Ray Kinnane

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2012