JAPANESE POTTERY AND LACQUERWARE

Ceramics makers in Otani Japanese ceramics are perhaps the best illustration of Japanese technical brilliance, refined aesthetics and feeling for nature and the concepts of “wabi” (quiet taste), “sabi” (elegant simplicity) and “shibui” (austerity). These overlapping concepts describe the cerebral and spiritual rather than mechanical and are used to describe things that are simple, refined, and contemplative.

Describing a first-rate set of Japanese tea bowls, ceramic expert Robert Yellin wrote in the Japan Times, "They have no fancy glazes or deftly painted iron underglaze designs; they just 'are.' Full and organic like the moon they quietly invite you pick them up. The balance is perfect, the touch almost sensual, and the feeling of holding earth, water, fire and air combined is very grounding."

Japanese potters value glazes whose colors echo the rural landscape — "rich reddish brown, derived from local stone, greens and creams made from rice husk ash and brownish-black resembling freshly turned earth."

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Traditional Crafts of Japan on Pottery kougei.or.jp ; Traditional Crafts of Japan on Lacquerware kougei.or.jp ; British Museum on Japanese Porcelain britishmuseum.org ; Arita Online (about Arita Ceramics) arita.or.jp ; Satsuma Pottery satsuma-pottery.com ; Japanese Imari japaneseimari.com ;Japanese Pottery Information Center e-yakimono.net ; Japanese Pottery Online Shopping japanesepottery.com ; Good Photos of Seto Ceramics at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Kansai Gaidai University Ceramics Course kansaigaidai.ac.jp ; Bizen (near Okayama) yaki ceramics, JNTO article JNTO ; Book: The Japanese National Tourist Organization publishes a booklet called “Ceramic Arts and Crafts in Japan”.

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Crafts: Traditional Crafts of Japan (Good, Detailed Site) kougei.or.jp ; Museum of Japanese Traditional Art Crafts nihon-kogeikai.com ; Craft Links japanesetemari.com/linksorientalculture ; American Society of Appraisers (to find the value of a Japanese craft) appraisers.org/ASAHome ;Japan -Shop.com japan-shop.com ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Lisa’s Japanese Pages lisashea.com ; Shibui Japanese Antiques shibuihome.com ;

Kyoto and Tokyo Crafts: Welcome to Kyoto Kyoto Prefecture Site ; Japan Guide apan-guide.com ; Nishijin Textile Center Nishijin.or ; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Traditional Industry (near Heian Shrine) is a relatively new museum. Not only does it have exhibits of various handicrafts made of silk, bamboo, lacquer, paper and ceramics, it also features demonstrations of centuries-old production methods by skills craftsmen and craftswomen. kyoto.travel ; Nezu Institute of Fine Art (Minami Aoyama) is a two- gallery museum set around a traditional garden, with a charming and eclectic collection that dates from 2000 B.C. to the 1920s and includes hanging scrolls, tea ceremony utensils, screens, bronzes, lacquerware, ceramics, kimonos, Chinese bronzes, lacquered pillboxes, Japanese swords, and ink drawings by Kano Maonobu. Nezu Museum site nezu-muse.or.jp

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Art: Artelino on Japanese Art artelino.com ; Web Japan web-japan.org/museum/paint.html ; Japanese Art Portal japaneseart.org ; ; Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Zeroland zeroland.co.nz ; Asia Society Virtual Tour asiasociety.org ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com

Art History Sites Art History Resources on the Web — Japan witcombe.sbc.edu ; Early Japanese Visual Arts wsu.edu:8080 ; Japanese Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Books: “History of Japanese Art” by Penelope Mason (Harry N. Abrams, 1993); “The People' Culture — from Kyoto to Edo” by Yoshida Mitsukuni (Cosmo Public Relations Corporation, Tokyo, 1986); “The Shaping of Daimyou Culture, 1185-1868" by Martin Collcut and Yoshiaki Shimizu (National Gallery of Art, 1988).

Art Museums in Japan Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Tokyo National Museum site tnm.go.jp ; Kyoto National Museum official site kyohaku.go.jp ; Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Nara National Museum narahaku.go.jp ; Kyoto University Museum inet.museum.kyoto-u.ac.jp ; National Museum of Art, Osaka nmao.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Tokyo tobunken.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Nara nabunken.go.jp/english ;Miho Museum near Kyoto miho.or.jp ; Photos danheller.com

Museums with Good Collections of Japanese Art Outside of Japan ; Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston mfa.org/collections ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art lacma.org/art ; Ruth and Sherman Lee Institute for Japanese Art Collection ucmercedlibrary.info

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAINTING Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EDO PERIOD ART Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; UKIYO-E, HOKUSAI, HIROSHIGE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE POTTERY AND LACQUERWARE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAPER CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TEA CEREMONY AND FLOWER ARRANGING IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GARDENS AND BONSAI IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Early Japanese Pottery

2000-year-old Yayoi pottery People living in Japan were the first known people to use pottery. Pottery from Japan dated to 10,000 B.C. is the oldest known in the world. Pottery is made by cooking soft clay at high temperatures until it hardens into an entirely new substance — ceramics. The pottery of the Jomon people was decorated with markings made by pressing lengths of cord into the wet clay before firing. The Jomon people, who lived from 10,000 and 400 B.C., made fantastic designs on the edges of their pottery and produced strange-looking ritual clay figurines that possibly represented gods or were symbols of fertility.

The Yayoi Period (400 B.C.-A.D. 300) is named after the Yayoi-type of wheel-turned pottery vessels produced during this period. The Yayoi people are believed to have come from the Korean peninsula about 300 B.C. Yayoi pottery resembles pottery produced in Korea at the same time.

Pottery making as an art form is generally regarded as beginning in the 13th century with the introduction of Chinese and Korean ceramic techniques and the founding of a kiln in 1242 at Seto in Aichi by an artisan named Toshihiro. The Japanese word for pottery and porcelain, “setomoro”, literally means "things from Seto."

In the 14th century five more kilns were established in Tokoname, Shigaraki, Bizen, Echizen and Tamba. Some regard the Old Tamba pottery of Hyogo Prefecture to be the most Japanese of all pottery styles. Together with the Seto they were known as the "Six Ancient Kilns" and were famous for providing high quality ceramics.

Porcelain

14th century pre-porcelain

Japanese Setoware Porcelain is a type of pottery made from kaolin, a fine whitish clay composed of quartz and feldspar, that becomes hard, glossy and nearly transparent when it is fired in a kiln. The word porcelain reportedly is derived from the Italian word porcella, meaning little pig, or possibly from a similar word meaning female pig genitals. The name was given first to a smooth, white, cowrie shell, and then to the smooth, white finish on porcelain pottery. The term “porcelain” was used in Marco Polo’s writings. Porcelain pieces can be dated by their inscribed reign marks.

True porcelain is made of fine kaolin clay and feldspar, also known as petuntse or Chinese stone. It is white, thin and transparent or translucent. Before it shaped the kaolin is mixed, filtered and vacuum pressed into slabs for aging.

Blue and white porcelain has traditionally been made from kaolin clay mined near Jingdezhen, a town in southern China, and mixed with a particular kind of cobalt imported from Persia. Other kinds of porcelain include underglaze red, underglaze blue, copper red (used for imperial ceremonies), "sweet-white," peacock blue and celadon green.

The Chinese made the earliest known porcelain around A.D. 700 and held a global monopoly on its production for over a thousand years. Chinese porcelain didn't reach Europe until the 14th century and the art of making porcelain wasn’t developed in Japan until the 16th century and in in Europe until the 17th century.

Porcelain evolved step-by-step from 5,000-year-old painted pottery through a process of refining materials and manufacturing. A greenish glaze applied to stoneware was developed in the early Han (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) dynasty. A glaze that resembled the sort used on porcelain was made in the early Sui dynasty. Celadons (See Below) evolved during the Six Dynasties period (A.D. 220-589).

Proto-porcelain evolved during the Tang dynasty. It was made by mixing clay with quartz and the mineral feldspar to make a hard, smooth-surfaced vessel. Feldspar was mixed with small amounts of iron to produce an olive-green glaze.

In China, porcelain was produced to be enjoyed on three levels: aesthetic, technical and symbolic. The ways the painted subject on porcelain interact often portrayed a meaning beyond the symbols. A five-claws dragon superimposed on tangerines and pomegranates, for example, links the royal family with fertility (pomegranates) and prosperity (tangerines).

Japanese Porcelain

17th century porcelain elephant Porcelain has been made in Japan for 400 years. In 1510, a Japanese potter named Shonzui visted the Chinese imperial porcelain factory and leaned the craft and brought back some material from China and made porcelain in Japan until his supplies ran out. Korean potters captured during the Japanese invasion of Korea in 1598 taught the Japanese advanced technologies for glazing stoneware and porcelain.

In 1616, a kaolin source was discovered in Arita in Saga Prefecture and Japan began producing its own Chinese-style porcelain there. Later, enameled and decorated porcelain made in Arita but named after Imari, the port from which it was shipped, were greatly treasured in Europe and copied by ceramics factories in Meissen, Germany, Delft, Holland and Worcester, England.

Sometsuke (blue-and-white cobalt underglaze ware) is a kinds of Chinese-style porcelain that originated about 300 years ago in Arita and was called Imariware had a profound influence on porcelain makes in Meissen.

In the Edo period, daimyos encouraged the building of kilns, particularly climbing kilns (“noborigama”), which were built on the sides of hills, contained as many as 20 chambers and had the capability of reaching temperatures of 1400̊C. Nabeshima and Kutani wares were two valued styles of Japanese porcelain that emerged in the 17th and 18th century.

In many ways, Japanese porcelain had more of an impact on European porcelain than the Chinese variety. Some of the most beautiful Japanese pottery was made by the 17th century artist Ninsei. Ninsei developed a unique Japanese style of ceramics in which enameled porcelain was applied to pottery to produce graceful, richly-colored natural designs. The potter Kakiemon produced porcelains with stylized brightly-colored paintings of birds and blossom that were copied by potters in Germany, France and Britain.

Certain families were famous for their pottery skills, The Nabeshima family of the Saga clan was known for producing spiderweb and tassel designs 250 years ago that appear quite avant garde today. The Nabeshima kiln produced works for the shogunate for more than 200 years. The first pieces were made Nabeshia Katsushige (1580-1657), the first lord of the Saga clan, who began producing some of Japan’s first porcelain when civil disturbance in China cut off the supply of porcelain from there.

Tea Ceremony and Japanese Pottery

Iga-type tea ceremony

flower vase Japanese ceramics flourished during the Momoyama Period (1573-1603) and it development as an art form was boosted by the popularity of the tea ceremony. Famous Oribe and Shinto tea ceremony ceramics were produced under the direction of tea master Furuta Oribe and Sen no Rikyo. The master potter Chojiro developed the raku-yaki style of pottery after being ordered to do so by the shogun.

Object used in the tea ceremony included special porcelain or ceramic bowls, a cast-iron kettle with bronze lid, freshwater water jars, ceramic of lacquer container for powdered tea, and tea caddies. There are four main principals defining the way people and tea objects interact: “wa” (harmony); “kei” (respect); “sei” (purity) and “jyaku” (tranquility).

Smithsonian curator for ceramics Louise Allison Cort wrote, the tea ceremony "played a special role in the development of distinctive Japanese view of materials. The host preparing to make tea assembled a group of utensils made of disparate but complementary materials...Juxtaposition and contrast of the materials within the compact space emphasized their distinctive qualities."

Within the tea ceremony "there developed the singular Japanese appreciation for tea bowls, vases and water jars made of unglazed stoneware clay — material relegated to utilitarian purposes elsewhere in the world. Terms such as "chilled" and "withered' were used to describe the emotional response to the wood-fired clay surface."

Since the 16th century, crafts, regarded as great works of art, have been created for the tea ceremony. These crafts have provided work for generations of highly-skilled craftsmen and workshops. It is not unusual for connoisseurs to shell out tens of thousands of dollars for a perfectly-made modern tea ceremony bowl and hundreds of thousands of dollars for a classic piece.

Porcelain from Arita is still made and sold. The Imari pattern usually refers to brocades. Brightly-colored Kakiemon birds and flowers are still valued. Other popular designs include scenes of legends and daily life rendered in blue and white.

Other major pottery centers include Satsuma-yaki (from Kagoshima), famous for porcelain with a cloudy, cracked glazed and enameled designs in gold, red, green and blue; Karatsu-yaki (from Karatsu, Kyushu), known for Korean-style tea ceremony objects made with grayish cracked glaze; Hagi-yaki (from Hagi), known for porcelain with a pale yellow or pinkish cracked glaze; and Bizen-yaki (from Bizen, Honshu), famous for chunky, unglazed bowls.

Top quality ceramics can also be found at Mashinko, Mino-kaiji at Toko, Temmoku-yaki in Seto, Kiyomizu-yaki in Kyoto and Kutani-yaki in Isjikawa.

Raku pottery refers to pottery produced by the Kobe-based Raku family for over 400 years or any handcrafted red or black glazed ceramics made with a potters wheel. Pieces actually made by the Raku family are held in high regard.. Tea ceremony sets made by the family are famous for their dramatic , modern style.

Japanese Pottery Makers

During the Meiji period interest in ceramics declined and then experienced a rebirth during the revival of popular folk arts led by Yanagi Soetsu (1889-1961), who is credited with generating interest not in just pottery bit in all traditional crafts during the early 20th century. Famous pottery makers include Kawai Kanjiro, Yoshihiko Yoshida, Seteguro Yoshida, Ken Matsuzaki, Tomimoto Kenkicho and Hamada Shoji.

The English potter Bernard Leach studied under Hamada. He is largely credited with developing an interest in Japanese ceramics in the West.

Some of the best pieces are made by plucking them from the kilns with tongs at the height of firing and rapidly cooling them. Many fine pieces have small blotches, where the potter hold he work while dipping it into a vat of glaze. They are not covered up because they are considered a thing of beauty in their own right.

Pottery Centers in Japan

There are more than 100 pottery centers in Japan. They produce everything form cheesy images of sake-swilling tanukis to $30,000 tea ceremony bowls.

One potter told National Geographic, Hagi-yaki ceramics "takes a lot of patience, and patience is hard to find these days. No one wants to take time anymore. I'm paid a salary. That's how the tradition is changing. People used to make handicrafts on their own and be satisfied to earn a little money. Now it’s a business. But Hagi-yaki will survive. As long as there's earth, the tradition will last." [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic. September 1994]

Statues of fat, jolly tanukis — Japanese mammals that resemble a cross between a badger and a raccoon — are the Japanese equivalent of garden gnomes. Found everywhere and said to bring good luck, ceramic tanukis commonly have a sake bottle in one hand, a passbook around their waist and sedge hat on their head. Some hold up a tool or object associated with profession or hobby of he owner. Statues outside restaurants and bakeries often carry a piece of cake or a bowl.

The town of Shigaraki in the Koga area near Kyoto is especially famous for its ceramic tanukis. The first major tanuki-making kiln was started by Tesuzo Fujiwara (1876-1966), who was reportedly inspired bu seeing a tanuki on a river bank beating its belly. Making the facial expressions is said to be the hardest part of making a tanuki statue.

Book: “The Road Through Miyama” by Leila Philip, about working with a Japanese potter in the countryside

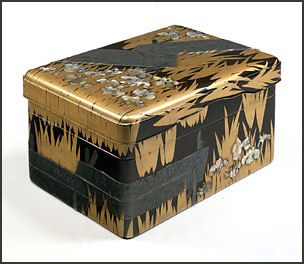

Lacquerware

18th century writing box Lacquerware refers to objects, usually boxes, covered with lacquer (a processed tree sap). In ancient times lacquerware was greatly prized partly because the large amount of skilled labor required to make lacquer objects. As many as 200 thin layers of lacquer were applied to some objects, with each coat require drying and polishing before the next layer was applied.

True lacquer is the sap or resin from the son (urushi, thitsi or varnish) tree. It has a peculiar buttery smell in paste form, and produces an intense allergic reaction in many people. It is not unusual for the hands of sufferers to swell to twice their normal size. Even though craftsmen who work with lacquer are not allergic to it they are careful to keep their hands covered.

James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ East Asian lacquer is a resin made from the highly toxic sap of the Rhus verniciflua tree, which is native to the area and a close relative of poison ivy. In essence, lacquer is a natural plastic; it is remarkably resistant to water, acid, and, to a certain extent, heat. Raw lacquer is collected annually by extracting the viscous sap through notches cut into the trees. It is gently heated to remove excess moisture and impurities. Purified lacquer can then be applied to the surface of nearly any object or be built up into a pile. Once coated with a thin layer of lacquer, the object is placed in a warm, humid, draft-free cabinet to dry. As high-quality lacquer may require thirty or more coats, its production is time-consuming and extremely costly.” [Source: James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer (1991), Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Lacquer is one of the strongest adhesives found in the natural world. It is resistant to water, acids, alkali and abrasion. Lacquer saps comes out of the tree creamy white like latex from a rubber tree and have traditionally been made brown or black by mixing then it with resin in an iron container fir 40 hours. Around 10 coats of lacquer are applied to a typical piece.

Lacquerware Traditions in China, Japan and Korea

James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Carved lacquer is a uniquely Chinese achievement in lacquer art and is also, in a way, lacquer art in its purest form. It is not known when this technique was invented. Lacquers of a thickness sufficient for relief carving were produced no later than the Southern Song period, as is known from archaeological excavations and from materials that were brought to Japan at the end of the Song period. This method of lacquer production reached its greatest flourishing from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century.” [Source: James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer (1991), Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“In Japan, on the other hand, the underlying shape of a lacquer object is never lost sight of and surface decoration is paramount. The earliest lacquer surface decoration known in Japan, apart from simple designs painted on lacquered objects of the prehistoric period, is the gold and silver foil inlay of the Nara period. Almost certainly this technique was transmitted from Tang China, the source of the dominant cultural influence on Japan at this time. However, once this technique of lacquer decoration had been introduced into Japan, it took on a life of its own and, in fact, continued to develop there into recent times. (Meanwhile, the same technique all but died out in China after the demise of the Tang dynasty in the tenth century.) During later periods, other metals were also used for inlay in Japan, such as lead, tin, and pewter. A technique developed to the highest degree in Japan is the use of gold and silver in powder form, either mixed in to form gold or silver lacquer, or sprinkled over the lacquer surface to create a graduated gold or silver effect. Indeed, the Japanese exploited every physical property of lacquer: as a liquid for painting; as a solid surface that can be built up in certain areas of the composition; and as an adhesive, especially for gold and silver (in either foil or powder form). The resultant works often display great subtlety and delicacy, and maki-e (gold or silver) lacquer is one of the supreme achievements of Japanese decorative art.\^/

“In Korea, too, it is known that lacquer surfaces were decorated with metal foil inlay more or less contemporaneously with the Tang dynasty in China, during Korea's Unified Silla period. In the subsequent Goryeo period, however, perhaps following the lead of southern China under the Song dynasty, mother-of-pearl inlay became the dominant decorative technique for Korean lacquer, and it has continued as such to the present day. Although lacquers of the Goryeo period exhibit some marked similarities to a certain class of mother-of-pearl inlaid lacquer produced in Song China, gradually Korean lacquer evolved a distinctive national style. The finest lacquerware of the late Goryeo and early Joseon periods makes rich use of mother-of-pearl inlay, often in combination with tortoiseshell, and gives an impression of great sumptuousness.\^/

Producing Lacquerware

High-quality lacquerware pieces take a long time make because many layers of lacquer are applied and each takes a long time to dry. When the process is finished the lacquer is polished to a brilliant shine.

Once lacquer becomes hard it is inert and extraordinarily durable. Contrary to what you would think, lacquer dries best in a humid atmosphere. Some craftsmen place their objects for several days after each lacquer application in special closets with the temperature set at 23̊C and the humidity is 80 percent.

The most common colors of lacquer are amber, brown, black and red. Additives can used to make violet, blue, yellow and even white lacquer. Green and violet shades can be achieved with reeki pigments developed in Japan in the early 20th century.

Over time lacquer cracks largely because of fluctuations in humidity and the gold and metal foil used as decoration peels away. Restoration involves painstaking cleaning, taking microscopic samples to see what material is best for strengthening the lacquer surface; applying lacquer from the urushi tree or a synthetic resin

Lacquerware Craftsmanship and Design

Lacquerware is usually made by coating split bamboo or wood with lacquer, then adding intricate hand-painted designs or inlays of gold or silver foil or other materials. Typical lacquerware is gold on black lacquer or yellow and green on a red brown background. Master craftsmen carved designs into the layers of lacquer without touching the wooden substrate. Foil has traditionally been kept in place with animal glue.

Describing a lacquerware craftsman, W.E. Garret, wrote in National Geographic, an artisan "first weaves a cylindrical frame of bamboo and horsehair, over which successive coats of sap from the thitsi tree are applied. After each layer has dried, a worker puts the cylinder on a lathe for polishing. Using a stick in his right to spin the lathe, he smooths the surface with pumice.

"An artist then creates a pattern by scratching a design and covering the container with pigmented lacquer. Another polishing removes all the color except that caught in the depressions. These steps are repeated with successive colors until a multi-hued design is complete. Some tell a love story; others include figures from astrology or folklore." [Source: W.E. Garret, National Geographic, March 1971.]

East Asian Lacquer Decoration Techniques

East Asian Lacquer Decoration Techniques: 1) Carved lacquer (diaoqi) is a method of decoration involves carving built-up layers of thinly applied coats of lacquer into a three-dimensional design. 2) "Engraved gold" (qiangjin) is decorative technique in which an adhesive of lacquer is applied to fine lines incised on the lacquer surface, and gold foil or powdered gold is pressed into the grooves. [Source: James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer (1991), Department of Asian Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

3) "filled-in" (diaotian or tianqi) is a decoration in which lacquer is inlaid with lacquer of another color. There are two methods of filled-in decoration: one involves carving the hardened lacquer and inlaying lumps of other colors; the other is called "polish-reveal" (see below). 4) Maki-e is the general term in Japanese for lacquer decoration in which gold or silver powder is sprinkled on still-damp lacquer.\^/

5) Nashiji is a Japanese lacquer technique that produces a reddish, speckled surface, also called "pear-skin," by the sprinkling of especially fine, flat metal flakes over the half-dry lacquer base. 6) "Polish-reveal" (moxian) is a variety of "filled-in" lacquer decoration. Thick lacquer is applied repeatedly in certain areas to build up a design; then the ground is filled with lacquer of a different color and the entire surface is polished down to reveal the color variations.\^/

Lacquerware in Japan

Japanese lacquerware is known for its gold leaf luminesce, bright patterns, and glossy finish. The Japanese have used lacquer since the Jomon period to protect wood and enhance its beauty. The production of “maki-e” — lacquerware with designs made from sprinkled powder of silver and gold — dates back to the 8th century. In the 17th century the word japan was used in English to mean applying a finish of black lacquer to something.

The world oldest known lacquer relics were created in Japan 9,000 years ago. In the early 2000s, a fire in the northern town of Minamikayable destroyed the world oldest known lacquer relics. The fire occurred in storehouse where 80,000 artifacts from Jomon period were kept. Some of the lacquer object were dated to 7000 B.C.

Some of the greatest lacquerworks were created by the Koami Nasashige a craftsmen who practice in Kyoto I the early 1600s.

Lacquer specialist, Yoshihiko Yamashita

Japanese Lacquerware Techniques

tapping an urushi tree Japanese lacquerware objects are dyed with a layer of logwood dye, then a dye made with rice vinegar and pieces of iron, the same material women used to used to use paint their teeth. After the drying process is complete the object is covered with layers of lacquer made from the sap.

The famous maki-e technique mainly uses images created by sprinkling gold or silver powder into liquid lacquer and sealing it with additional coats of lacquer. The gold and silver are usually placed over a red or black lacquer background and covered with transparent layers of more lacquer.

Once, to make a lacquered image of a crane on a lacquer box, human treasure Gonroku Matsuda needed a precise shade of white from quail eggs. The only problem is that quail eggs are not all the same color and Matsuda had to go through 2,300 eggs before he found 24 that matched perfectly. When the ordeal was over he said he would never eat a quail egg again. [Source: William Graves, National Geographic, September 1972]

Lacquered Japanese Tableware

Lacquered tableware is known as shikki in Japanese. The glossy and stately look of lacquered plates and tableware adds a dignified and luxurious look to food. They are often used for special cuisine such as New Year's traditional osechi food, but they can be fashionable and cool to use for everyday meals. Essayist Hiroko Takamori, who organizes special events in Tokyo galleries. Told the Yomiuri Shimbun, "The feel of shikki when you hold and use it is very pleasant. I want more people to use it everyday," said Takamori, who has written many books about lacquerware. [Source: Sanae Nokura, Yomuri Shimbun, October 21, 2011]

Takamori's parents are from Wajima, a northern city of Ishikawa Prefecture, well-known for its production of lacquerware. Her gallery displays soup and rice bowls, spoons, cups and other lacquered tableware with simple designs suitable for daily use. A soup bowl, for example, costs about 10,000 yen. "I want visitors to enjoy the feel of lacquerware when they hold it. It feels like it belongs in your hand," she said.

One of the appeals of lacquerware, she says, is "it's toughness and durability." "Lacquer becomes harder over time and the more you use it, the more shiny the gloss becomes," she said. A soup bowl Takamori has used for about 20 years has a unique gloss and a somewhat transparent look that cannot be seen in a brand-new bowl. "Lacquerware projects an interesting and distinctive aura as you keep using and washing it," Takamori said. "It's fun to 'grow' lacquerware."

Takamori recommends a wood bowl for everyday use. "The temperature [of the food inside] is gently felt through a wood bowl. No matter how hot or cold [the inside of the bowl] is, it feels good through [a bowl] made of wood," she said, adding the heat of really hot tea turns to a comfortable warmth through a lacquered wooden cup.

It may seem inconvenient to clean or maintain lacquered tableware, but Takamori said it's the same as other types of tableware. She recommends washing lacquerware with a soft nonabrasive sponge using regular kitchen soap and rinsing it with cold or warm water--whatever is the more "comfortable temperature for your hands"--and gently wiping it dry. Don't put it in a microwave or a dishwasher. It's also better not to store shikki with ceramics, metals or items harder than lacquerware to avoid scuffing or scratching. If a piece is damaged, bring it to a shop or lacquerware specialist and ask how to get rid of the marks, she said.

Image Sources: 1) Association for the Promotion of Traditional Crafts Industries in Japan 2) National Museum in Tokyo, 3) British Museum, 4) drawings JNTO

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of ArtNew York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2016