WASHI

fitting the screen Even paper and papermaking are art forms in Japan. Craftsmen make “washi” (traditional Japanese paper) by hand from the silken fibers of the inner bark of the “kozo” (paper mulberry tree) as their ancestors did centuries ago.

Small villages such as Kurodani and Fatamata near the Inland Sea are famous for producing washi. Papermaking families in the village of Kurodani are related through intermarriage, a custom that was employed to keep papermaking techniques a secret.

Paper arrived in Japan from China via Korea around the year A.D. 600 and was developed in the town of Echizen in Fukui Prefecture west of Kyoto. In the Heian period washi was greatly prized by members of the Imperial court in Kyoto and used for writing poetry and diaries.

Early Shinto priests believed that paper was a symbol of beauty, purity and perfection. Even today ritually folded paper is presented as an offering and Shinto priests use paper pom poms in their blessing ceremonies.

Good Websites and Sources: Washi About Washi apanesepaperplace.com ; Video of Making Washi Paper woodblockdreams.blogspot.com ;Awagami Paper Factory awagami.com ;

Paper Art, Umbrellas and Lanterns Good Paper Art Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Good Lantern and Umbrella Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de Origami: K’s Origami origami.ousaan.com/ ; Contemporary Origami origami.gr.jp/~hojyo ; Nippon Origami Association origami-noa.com ; History and Mathematics of Origami thinkquest.org ; Origami Gallery (in Japanese) geocities.jp/miwamero99 ; Origami Tanteiden origami.gr.jp ; Joseph Wu Origami origami.as ; Origami Tanteidon of the Japan Academic Origami Society origami.gr.jp ; Origami.com origami.com ;

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Crafts: Traditional Crafts of Japan (Good, Detailed Site) kougei.or.jp ; Museum of Japanese Traditional Art Crafts nihon-kogeikai.com ; Craft Links japanesetemari.com/linksorientalculture ; American Society of Appraisers (to find the value of a Japanese craft) appraisers.org/ASAHome ; Japan -Shop.com japan-shop.com ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Lisa’s Japanese Pages lisashea.com ; Shibui Japanese Antiques shibuihome.com ;

Kyoto and Tokyo Crafts: Welcome to Kyoto Kyoto Prefecture Site ; Japan Guide apan-guide.com ; Nishijin Textile Center Nishijin.or ; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Traditional Industry (near Heian Shrine) is a relatively new museum. Not only does it have exhibits of various handicrafts made of silk, bamboo, lacquer, paper and ceramics, it also features demonstrations of centuries-old production methods by skills craftsmen and craftswomen. kyoto.travel ; Nezu Institute of Fine Art (Minami Aoyama) is a two- gallery museum set around a traditional garden, with a charming and eclectic collection that dates from 2000 B.C. to the 1920s and includes hanging scrolls, tea ceremony utensils, screens, bronzes, lacquerware, ceramics, kimonos, Chinese bronzes, lacquered pillboxes, Japanese swords, and ink drawings by Kano Maonobu. Nezu Museum site nezu-muse.or.jp

Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Art: Artelino on Japanese Art artelino.com ; Web Japan web-japan.org/museum/paint.html ; Japanese Art Portal japaneseart.org ; ; Japanese Art and Architecture from the Web Museum Paris ibiblio.org/wm ; Zeroland zeroland.co.nz ; Asia Society Virtual Tour asiasociety.org ; Daruma, Japanese Art and Antiques Magazine darumamagazine.com ; Art of JPN Blog artofjpn.com

Art History Sites Art History Resources on the Web — Japan witcombe.sbc.edu ; Early Japanese Visual Arts wsu.edu:8080 ; Japanese Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Books: “History of Japanese Art” by Penelope Mason (Harry N. Abrams, 1993); “The People' Culture — from Kyoto to Edo” by Yoshida Mitsukuni (Cosmo Public Relations Corporation, Tokyo, 1986); “The Shaping of Daimyou Culture, 1185-1868" by Martin Collcut and Yoshiaki Shimizu (National Gallery of Art, 1988).

Art Museums in Japan Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Tokyo National Museum site tnm.go.jp ; Kyoto National Museum official site kyohaku.go.jp ; Tokugawa Art Museum tokugawa-art-museum. ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; Nara National Museum narahaku.go.jp ; Kyoto University Museum inet.museum.kyoto-u.ac.jp ; National Museum of Art, Osaka nmao.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Tokyo tobunken.go.jp ; National Research of Cultural Properties Nara nabunken.go.jp/english ;Miho Museum near Kyoto miho.or.jp ; Photos danheller.com

Museums with Good Collections of Japanese Art Outside of Japan ; Columbia University Page on Collections of Japanese Art columbia.edu ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston mfa.org/collections ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Los Angeles County Museum of Art lacma.org/art ; Ruth and Sherman Lee Institute for Japanese Art Collection ucmercedlibrary.info

Links in this Website: JAPANESE CULTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CULTURE AND HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSICAL JAPANESE ART AND SCULPTURE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAINTING Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EDO PERIOD ART Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; UKIYO-E, HOKUSAI, HIROSHIGE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE POTTERY AND LACQUERWARE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE PAPER CRAFTS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TEA CEREMONY AND FLOWER ARRANGING IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GARDENS AND BONSAI IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Washi continued be a major industry until 1870 when Western paper was introduced. Now, the art is dying however. In the 1970s there were about 800 households making paper. By the 2000s there were only 360.

Making Washi Paper

taking the screen from the sheet To make washi, mulberry branches are boiled in a wide iron pot. When the bark is soft it is peeled off and soaked overnight in water. The inner layers of the bark are then separated, dried in the sun and bleached white by boiling it in water with lye and ashes. The fibers are then hammered with a wooden mallet and rinsed to get the lye out. After the fibers have been picked clean of impurities they are mixed into a watery gruel in a vat with mulberry paste or “neri” (a material derived from arrowroot that prevents clumping).

Washi is made in a few different ways. In one method, the gruel is collected with a bamboo sieve, drained on a flat board, and repeatedly pressed with a long roller to get the waste out. In the rolling process a sheet is laid onto a board which is then laid in a frame and pressed with a big stone before being individually dried. The result is a big square sheet of paper.

In another method the papermaker dips a “sugeta” (a paper mold consisting of a wooden frame and a removable screen of split bamboo stalks) into the vat, lifts it and shakes the watery gruel through the screen. The rectangular, oatmeal-colored material that remains in the frame dries into paper.

One thing that distinguishes Japanese papermaking from Chinese papermaking is that the paper gruel is repeatedly scooped onto a sifting tray and “shaken” horizontally. This process is done until the fibers have coalesced into a sheet with a smooth feel. Chinese paper is simply drained and the result is paper with a rougher feel.

Objects Made from Paper in Japan

A wide variety of washi products are available in Japan. Many can be found in specialty stores that sell nothing but paper items. Because the fibers in washi make it much stronger than the paper used for writing and reading, washi can be used to make things like room-size kites, umbrellas, fans and walls and windows in traditional homes. Kimono sashes made from handmade paper sell for as much as $5,000. Colors and silver and gold leaf are added to washi to make designs. Sometimes special washi is made to enhance the emotional quality of a particular poem or work of calligraphy.

Many traditional Japanese homes have “shoji” (sliding paper screens) instead of walls. One Japanese artist told National Geographic that shoji creates a "good feeling" because "behind the shoji screen we cannot really see you, but we can know your actions, whether or not your are lively." Shoji windows infuse traditional homes with a soft natural light. "The best condition of paper is between eye and light," one papermaker said. "I can feel the life of the fiber. I can hear it. Perhaps we respond because of our own veins and arteries. We are knitted and connected, like the fiber."

“Wagasa”are traditional Japanese umbrellas made combining paper sheets of different colors and coating them with water-repelling oils. They require a great deal of labor to make in part because they have up to 50 ribs. It takes many hours and more than 10 craftsmen to a single wagasa made the traditional way. The craftsmen include “honeshi”, who make the ribs from bamboo; “tsunagiya”, who tie the ribs with dyed chord; and “harishi”, who pare the frame.

To make a proper wagasa takes about 20 steps including coating the paper and the 52 ribs with a mixture of linseed oil and paulownia oil and binding the ribs with string. If the pieces are not fitted together properly the umbrella will not open smoothly. The Yamagata region has been famous for wasaga since the 1780s when local samurai started making them by hand on the urging of local lords.

Japanese Fans

Folding fans was invented in Japan in the A.D. 6th century as an adaption of screen fans introduced from China. They consist of a solid silk cloth attached too a series of sticks than can collapse on one another. In the 10th century the silk cloth was taken out and substituted a series of "blades” made of bamboo or ivory" which were threaded together to make up the fan. Over the years "dance" fans, "court" fans, "tea' fans, "riding" fans and even "battle" fans have been developed in Japan.

“ Sensu “ are traditional Japanese folding fans. Uchiwa are one piece fans with handle. Uchiwa is literally translated as "paper-fan.” Yoshiko Uchida wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun. “Ibasen is a long-established store in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, that specializes in uchiwa and sensu. Opened in the early Edo period (1603-1867), the store offers a great range--variations include the length of the handle, the size of the uchiwa face, the pattern it bears and the material used, which is most often washi paper or fabric. The price tags also cover quite a range, from a few hundred yen to more than 10,000 yen.” [Source: Yoshiko Uchida, Yomiuri Shimbun, July 15, 2011]

Small uchiwa that can easily be carried around in a bag have been popular in recent years, but according to Nobuo Yoshida, the 14th owner of Ibasen, nowadays the trend is turning toward larger fans, possibly because people "want to make a strong breeze this year, when electricity conservation is required." The shape of a fan's face can also help on this front. A wide, elliptical uchiwa is said to move a lot of air with little effort.

Uchiwa have been used in Japan for ages, and they are even featured in wall paintings in ancient tombs. It is believed that in ancient times, uchiwa were used as ritual tools to remove negative vibes. "They came to be produced en masse during the Edo period, and were used widely in everyday life. It is thought that people used uchiwa to make fires for cooking and to shoo away insects," Yoshida said.

Today, places known as uchiwa production centers include Marugame, Kagawa Prefecture, Minamiboso and Tateyama in Chiba Prefecture, and Kyoto. Each area has its own characteristics. Marugame uchiwa can be identified by their flat handles made of whittled bamboo. In the case of Kyo uchiwa from Kyoto, the central supporting "rib" of the uchiwa face is not an extension of the handle. Rather, a completely separate wooden handle is attached.

Boshu uchiwa from Chiba Prefecture are also called Edo uchiwa, since the tool is believed to have originated in Edo, the former name for Tokyo. Ibasen deals mainly in Edo uchiwa, which have solid bamboo handles that are split at the top into multiple strands that serve as the ribs. The round handles fit comfortably in the palm, which makes for easy operation. "The bamboo handle is split into as many as 48 to 64 ribs," said Yoshida, explaining the labor-intensive process of making Edo uchiwa.

The beauty of the design is an important consideration when choosing uchiwa. Uchiwa bearing colorful ukiyo-e woodblock prints have a special personality. Ibasen sells uchiwa decorated with prints based on the work of such famous ukiyo-e artists as Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Utagawa Toyokuni. Classic summer motifs like morning glory flowers and traditional designs like black-and-white checks and ocean waves project a stylish elegance.Uchiwa made with fabric like tenugui or yukata cotton cloth are also popular nowadays. Fabric uchiwa with clover or penguin patterns suit even casual outfits.

Japanese Kites

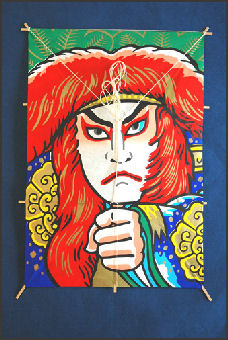

Aomori Prefecture is famous for hand-painted kites. The kite frames are made of “hiba” (cypress) wood. When painting a fierce warrior on a kite, the kite master first paints the outlines with black sumi, or Japanese ink. To get the expression just right, the eyes are painted with th utmost care, followed by the mouth, chin and nose.

The images on these kites resemble those found on traditional Japanese woodblock prints. Dyes are used to create the colors. They are preferable to paints because they look better when the sun shines through them while the kite is in the sky. Eight or nine colors are commonly used, with red and blue being the dominant colors. Some kites have a piece of washi paper glued to the string. It creates a buzzing noise when the kite is flown.

Room-size kites are made of cypress wood, string and light handmade Japanese paper and painted with images of warriors. Kites used in kite fighting may be 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) in size.

The Shirone Takogassen kite fighting festival in Shirone, Niigita prefecture features over 300 kites made from bamboo and washi paper that can be as large as 23-x-17 feet and weigh as much as 50 kilograms are used. Each kite has a unique design that has in some cases remained unchanged for three centuries. Tsugaru kites are often decorated with well-known historical figures. Many have ukiyoe-style pictures. The rope is made at great expense from hemp.

Origami

cranes Origami is the ancient Japanese art of paper folding. In school, nearly every Japanese child learns to make folded paper cranes (which brings good luck and are left as offerings to the heal the sick). At home families relax and share time together by making origami animals around the dinner table. Skilled practitioners of the craft can make squids, snakes, elephants, butterflies, centipedes, dragons, ox-drawn carts and sumo wrestlers. The only rules for origami is the folder must use one square piece of paper and not tear or cut the paper in anyway. A crane with four basic parts — the head, tail and two wings — is relatively simple to make.

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic: “One sheet, no cuts: Even in its simplest form, origami, the art of paper folding, generates enchantment. Since the earliest known manual, A Thousand Cranes, was published in Japan in 1797, flocks of paper birds have alighted on countless windowsills. But these days, the ancient art is being revitalized by another form of expression: math. By describing their work mathematically and modeling it with computers, origamists have jumped from paper to metal and plastic and from toy to technology. Folded creations have flown in space; someday one may lodge in your artery.[Source: National Geographic, Jennifer S. Holland, September 2009]

"The Japanese invented paper folding more than a thousand years ago," wrote Peter Engel in Discover magazine, "and endowed it with a aesthetic principals at the heart of their culture. That meant cultivating an art of understatement, of suggestion. Origami implies without announcing outright, intimates without brashness."

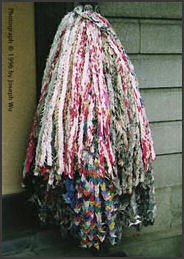

There is a saying that if you fold 1,000 cranes your dream will come true. Diagrams for classic origami cranes were published in 1797 in “The Secret of Folding a Thousand Cranes”. The world's largest origami is paper crane with a wingspan of 117.2 feet made in six hours by the residents of Gunma, Maebashi in October 1995.

These days some designs are incredibly complex and require supercomputers to sort out the details and when they are finished you can’t believe they are made from a single piece of paper. In Japan it s possible for mathematician to get a Ph.D, in origami studies. “It’s now mathematically proven that you can pretty much fold anything,” physicist Robert J. Lang told National Geographic. He quit his job in Silicon Valley eight years ago to fold things full-time, including centipedes with a full set of limbs and snakes with a thousand scales. “We’ve basically solved how to create any appendage or shape.” Each appendage consists of a folded flap of paper, and each flap, origamists realized in the 1990s, uses a circular portion, or a quarter or half circle, of the original square. It was a crucial insight, Lang says, because it allowed them to connect their basic problem — how to plan creases that will give a sheet of paper a desired shape — to a centuries-old mathematical puzzle: how to pack spheres into a box or circles into a square. [Op Cit, Holland]

Websites: Origami Page: www.origami.vancouver.bc.ca/index.html; Origami: www.origami.com ; Origami Tanteidan: www.origami.gr.jp /; Origami House (www.origamihouse.jp ).

Origami Folds and Bases

hundreds of oragami cranes There are two basic folds in origami: the mountain fold in which the paper sticks up like a pup tent and the valley fold which is essentially the same thing in reverse. From these more complex folds are made. Valley folds with each corner of a square folded so that they meet on the center create some that looks like a cheese blintz and thus is called blintz fold. More sophisticated fold include the petal fold and double blintz.

“Base” is a term that paper folders use for geometric shape that gives rise to a variety of models, The Japanese developed four of these, known as the kite base, the fish base, the bird base and the frog base.

"Each base,” wrote Engel, “offers a different configuration of flaps that can be used to represent a feature of an animal: head, neck, arms, legs, wings, horns, antennae, tail. The kite base offers a single flap, the fish base two flaps, the bird base four flaps, and the frog base five flaps. I made dozens of variations on the four fundamental bases, including an angelfish, a hummingbird, a penguin and a giraffe."

Complex Origami

Up until the mid 20th century origami practitioners were limited to a few hundred classic and oft-repeated designs, Then in the 1950s, new techniques and designs created by Japanese origami artist Akia Yoshizawa were published and demonstrated. Not long after that mathematicians began using analytic geometry, linear algebra, calculus and graph theory ro solve origami problems.

Using computer programs employed by physicists, origami folder Robert Lang makes amazingly sophisticated creatures such as praying mantis with six legs, a life-size Atlantic lobster, a ruby-throated hummingbird and full-scale human. Such work take more than 100 steps to complete. He told Discover magazine, “All the parts of the base are linked together and can’t be altered without affecting the rest of the paper, so that’s the part you have to calculate just right. Figuring out how to make god legs was all people did for years. Doing a six legged beetle was a big, big deal.”

Most advanced origami folders are engineers or mathematicians. Lang worked as a laser physicist at Cal Tech and at a Silicon Valley firm before quitting to devote himself to origami. He has made more than 500 new intricate origami models — turtles with patterned shells, raptors with textured feathers, a rattlesnake with 1,000 scales and a tick the size of a popcorn kernel — that required hundreds of folds. His masterpiece, first created in 1987, is 15-inch tall Black Forest cockatoo complete with claws and erect head feathers. When asked by Japanese television to demonstrate how it was made, the folding took more than five hours.

Lang and Japanese origami master Toshiyuki Meguro simultaneously hit on a technique that has revolutionized folding. Now called “circle river-packing” the technique allowed origamists to create models with realistic appendages in specific places, The technique allows origamists to work out the flaps (appendages) of the pieces and the space in between in advance without endless trial and error,

Origami Savant

Satoshii Karniya, a Japanese savant, created an extraordinarily complex, eight-inch-tall dragon with eyes, teeth, a curly tongue, whiskers, a barbed tail and a thousand overlapping scales. It took 40 hours to make spread over several months.

Karinya created the dragon when he was 23. He started folding paper with is mother when he was two and showed talent for visualizing complex geometric shapes at an early age. He has won the Origami TV champion in Japan several times. In one competition he to made an origami fish underwater.

On the dragon Karniya told the Daily Yomiuri,” I don’t remember how many days I spent...I made it through trial-and-error. Before I start folding the paper, I already have an image of the completed creation in my head, and just try to cast my idea into a shape.” He told Discover, “I see it finished. And then...I unfold it, in my mind. One piece at a time.”

Origami Applications

Origami has industrial and military applications. The container industry is very interested in different ways to fold a single sheet of material into useful objects. Diamond cut patterns have used in torpedoes and underwater fish farms.

Scientists and mathematician say that origami holds solutions from problems in fields as diverse as automobile safety (working out how to bend sheet metal and fold up air bags) , space science (determining the best way to fold objects like solar panels and parts for large space-based telescopes), architecture and medicine (developing stints that can be places in arteries and expand).

Lang has been hired by car makers to come up with better ways to stuff air bags into the steering column of automobiles and has developed plans for a space telescope that fits into a nine-meter tube and can extend to the length of a football field.

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic: “Mining the theory allowed origamists to plot complex designs with lots of limbs and also to find technological applications. When engineers working on the design of car air bags asked Lang to figure out the best way to fold one into a dashboard, he saw that his algorithm for paper insects would do the trick. “It was an unexpected solution,” he says. [Source: National Geographic, Jennifer S. Holland, September 2009]

“It was not, however, the first practical application of origami,” Holland wrote. “In 1995 Japanese engineers launched a satellite with a solar array that folded in pleats like a map — an easy-opening kind invented by mathematician Koryo Miura — to fit into a rocket. Once in space, it opened flat to face the sun. Lang has since helped design a space telescope lens the size of a football field that collapses like an umbrella. Only a prototype exists so far, but even that unfolds to nearly 17 feet.”

Researchers are also working at the other size extreme, creating origami stents to prop open arteries and boxes made of self-folding DNA, billions of times smaller than a rice grain, to ferry drugs to diseased cells. Talk to one of these modern origamists and you’ll see a new future unfolding. Someday, says MIT’s Erik Demaine, “we’ll build reconfigurable robots that can fold on their own from one thing into another,” like Transformers. And someday, Lang thinks, all the myriad components of a building might be made from the same simple sheets, folded in myriad ways. “We haven’t reached the limits of what origami can do,” he says. “We can’t even see those limits.”

Japanese Pencil Freak

Shoji Ichihara wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Sharpening a pencil can also sharpen your sense of vision, touch and hearing. Learning to savor this common writing utensil is the concept of Kangaeru Enpitsu (The Thinking Pencil), a book that may make you feel like sniffing pencil shavings after reading it. The book, subtitled "How to Hold, Cut, Write, Carry, Smell & Love: The Complete Pencils," is by author, Kyo Kohinata, has written many articles about stationery goods for magazines and other publications. [Source: Shoji Ichihara, Yomiuri Shimbun, August 3, 2012]

At Fred & Perry, a stationery shop in Tokyo's Ginza district, Kohinata said pencils write in different ways depending on how they are sharpened and held as well as the writing surface beneath the paper.What amazed me the most was Kohinata's ability to appreciate the shapes of pencil shavings and their aroma. As she opened the drawer of a pencil sharpener, she said, "Ah, smells good and relaxing." She seemed enraptured as she sniffed inside the drawer, not unlike a sommelier savoring the aroma of nice glass of wine.

The shape and thickness of a pencil's body, the width and smoothness of its lead and the degrees of its point's sharpness--these can all be "customized freely." This is impossible with other writing utensils such as ballpoint or fountain pens. Pencils allow users to "fine-tune" them before use. That's why they serve as "the best item to encourage users to think creatively," according to Kohinata.

Kohinata does not disdain computers and cell phones. "I use electronic devices a lot myself," the pencil enthusiast said. But there is a reason she is attracted to the retro writing tool. "At first glance, it looks inconvenient, but a pencil is actually fun because you can have a good time customizing it," she said. "Once you realize that, I think you will appreciate its versatility.” To write The Thinking Pencil, Kohinata said she only used pencils, an eraser and paper.

Floating Paper Cutting

Motoki Nakashima wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Unique paper cutouts, known as kiri-e in Japan, are hung on the wall just in front of a board...The paper is hung five to 10 millimeters in front of a mat board. It creates beautiful shadows that make the art pop out and appear 3-D. This style, called "ukabu kiri-e" (floating paper cutout), was invented by Migiwa Kawahara, 70. The artist began making kiri-e in 1970 after becoming fascinated with Chinese paper cutting called jian zhi, and mimicking the cutting technique. [Source: Motoki Nakashima, Yomiuri Shimbun, May 18, 2012]

Ukabu kiri-e was the product of chance, Kawahara said. Once framed, there is no difference between a paper cutout that is stuck on a board and a print of the same design. Kawahara made ukabu kiri-e because he wanted his work to be more visually impressive. Kawahara smiled and said he is happy when people look at his work and try to find the gaps between the kiri-e and the board.

The artist has been cutting paper for more than 40 years. Despite his vast experience, Kawahara said it is impossible to control the shadows that his art creates. "I have more to learn about kiri-e. That's why my interest in this art never wanes," Kawahara said. Kawahara teaches his art style at Kiri-e Kappa-kai at Bishamonten Zenkokuji temple in Kagurazaka, Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo.

Image Sources: 1) and 2) Ray Kinnane 3) and 4) Goods from Japan, 5) and 6) Japan Zone, 7) and 8) ) xorsyst blog

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013