SAMURAI

The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or daimyo, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armor and behavior on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could read and they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry. [Source: Tom O’Neill, National Geographic, December 2003]

Samurai endured for almost 700 years, from 1185 to 1867. Samurai families were considered the elite. They made up only about six percent of the population and included daimyo and the loyal soldiers who fought under them. Samurai means “one who serves.”

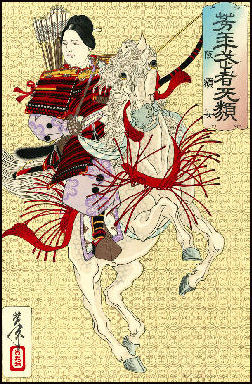

According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “The military elite dominated Japanese politics, economics, and social policies between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries. Known as bushi or samurai, these warriors, who first appear in historical records of the tenth century, rose to power initially through their martial prowess—in particular, they were expert in archery, swordsmanship, and horseback riding. The demands of the battlefield inspired these men to value the virtues of bravery and loyalty and to be keenly aware of the fragility of life. Yet, mastery of the arts of war was by no means sufficient. To achieve and maintain their wealth and position, the samurai also needed political, financial, and cultural acumen. [Source: Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of “bu” (“the way of life of the warrior”) and “bun” (“the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai”). Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesized in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality.The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com; NINJAS IN JAPAN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; NINJA STEALTH, LIFESTYLE, WEAPONS AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTO YORITOMO, GEMPEI WAR AND THE TALE OF HEIKE factsanddetails.com; KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM AND CULTURE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on the Samurai Era in Japan: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Samurai Women on About.com asianhistory.about.com ; Samurai Armor, Weapons, Swords and Castles Japanese Swords Blade Diagrams ksky.ne.jp ; Making the Blades www.metmuseum.org ; Wikipedia article wikipedia.org ; Putting on Armor chiba-muse.or.jp ; Castles of Japan pages.ca.inter.net ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese shirofan.com ; Seppuku Wikipedia article on Seppuku Wikipedia ; Tale of 47 Loyal Samurai High School Student Project eonet.ne.jp/~chushingura and Columbia University site columbia.edu/~hds2/chushinguranew : Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindex; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Samurai scholar: Karl Friday at the University of Georgia.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “A History of the Samurai: Legendary Warriors of Japan” by Jonathan Lopez-Vera and Russell Calvert Amazon.com; “Samurai: An Illustrated History” by Mitsuo Kure Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Guide to Samurai History and Culture: From the Age of Musashi to Contemporary Pop Culture” by Gavin Blair and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “Samurai: A History (P.S.)” by John Man Amazon.com; “The Way of the Samurai” (Arcturus Ornate Classics) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com; “Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan” (1899) by Inazo Nitobe, inspired by film “Last Samurai” Amazon.com; “The Samurai Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Guide to Japan's Elite Warrior Class” by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “The Book of Five Rings” by Miyamoto Musashi Amazon.com; “Musashi” , a novel about the legendary swordsman by Eiji Yoshikawa. (1995) Amazon.com; “The Lone Samurai: The Life of Miyamoto Musashi” by William Scott Wilson Amazon.com; “Samurai and Ninja: The Real Story Behind the Japanese Warrior Myth that Shatters the Bushido Mystique” by Antony Cummins Amazon.com; “Vagabond”, a popular 27-volume manga based on “Miyamoto Musashi” by the famous mangaka Takehiro Inoue Amazon.com; “Shogun & Daimyo: Military Dictators of Samurai Japan” by Tadashi Ehara Amazon.com; “Lords of the Samurai: The Legacy of a Daimyo Family” by Yoko Woodson , Melissa M. Rinne , et al. Amazon.com; “The Birth of the Samurai: The Development of a Warrior Elite in Early Japanese Society by Andrew Griffiths Amazon.com; “The Heart of the Warrior: Origins and Religious Background of the Samurai System in Feudal Japan” by Catharina Blomberg Amazon.com; Films: “Seven Samurai” Amazon.com and “Throne of Blood” Amazon.com; by Akira Kurosawa; “The Last Samurai” with Tom Cruise Amazon.com; ; “Twilight of a Samurai” Amazon.com; , nominated for an Academy Award in 2004

Samurai-Era Social Hierarchy

In Japan, a strict hierarchy of social classes and clearly defined traditional gender roles have their roots in over two thousand years of cultural history. In terms of social classes, merchants or chyonin were beneath the farmers and artisans. Samurai, the social elite, were retainers in the service of the shogun and the daimio. The samurai, who represented the superior male, constituted a bureaucratic and conservative hereditary group. The samurai and his sword was more a class symbol than the fierce warrior pictured in American television mythology. [Source: Yoshiro Hatano, Ph.D. and Tsuguo Shimazaki Encyclopedia of Sexuality, 1997 ]

According to Hierarchy Structure: “Ancient Japan social hierarchy demonstrates the classification of Japanese people on the basis of certain rules and conditions that were followed by Japanese society in ancient times. These social classes were categorized based on power as well as prestige. Ancient Japanese social hierarchy was majorly segregated into two classes the upper Noble Class and the lower Peasant Class. These classes were further sub categorized and thus forming a hierarchy. Following are the major classes in the social hierarchy of Ancient Japan: A) Upper Class – The Noble Class: 1) The King or the Emperor; 2) Daimyo; 3) Samurai. B) Lower Class – The Common Man or the Peasant Class: 1) farmers; 2) artisans / craftsmen. [Source: Hierarchy Structure hierarchystructure.com ]

A) Upper Class: 1) The King or the Emperor was the top most rank in the hierarchy. The Emperor possessed the supreme power among all the classes. The order of an Emperor was considered the final decision and no person was allowed to deceive that order. They ruled the kingdom and handled the administration. The Emperor was equivalent to the God for the countrymen.

2) Daimyo: The second in this class was the Daimyo. These people were also referred as the warlords. They mostly got the status and position of a Shogun and possessed the entire military as well as the economical power of the kingdom. The country’s security was under their leadership and responsibility. 3) The Samurai: The Samurai were the brave soldiers that constituted the armies led by Daimyos. They protected the entire Nation with their bravery and heroism.

B) Lower Class – The Common Man or the Peasant Class: The Common Man was the lowest class in this hierarchy and they possessed almost very few rights. They performed day to day working which a common man does to earn a livelihood. This class was further divided into many sub-categories. A brief description is as follow: 1) The Farmers: The Farmers were the topmost Class in the common man class in the ancient Japanese social hierarchy. This further incorporates two sub categories as the Farmers having their own land and the Farmers not having their own land. Former were superior to the latter. 3) Artisans / Craftsmen: This was the second class in the common man class. Their work was with metal and wood and some of them got famous as ardent Samurai’s Sword maker. 4) Merchants: Merchants was the lowest class in the common man class in the hierarchy because it was thought that their earning is totally dependent on other people’s work but later on the trend did change.

Taira no Masakado, the First Samurai?

Taira no Masakado

The great folk hero Taira no Masakado is sometimes referred to as the first samurai. A 10th century historic figure, he is famous throughout Japan as a rebel who challenged the Imperial Court, and as perhaps the scariest ghost that ever haunted the land. Heir to a great family fortune, Masakado was also a charismatic leader and skilled field general, which he proved time and time again in successful military campaigns against other local chieftains. [Source: Kevin Short, Yomiuri Shimbun, September 8, 2011]

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri Shimbun, “In those days, Japan was ruled by the Emperor in Kyoto, with official magistrates sent out to govern and collect taxes in outlying provinces such as the Kanto. Masakado, on one of his military forays, got a bit carried away. He attacked the local government compounds, and eventually declared himself emperor of eastern Japan.”

“Naturally, the Imperial Court could not tolerate such an affront to its sovereignty, and quickly dispatched troops to hunt the rebel down. Masakado, however, was operating on his own turf, and proved to be elusive prey. Official history books assert that eventually he was killed in a pitched battle with the government troops, but local legends hold that he was betrayed by his wife.

In one version of this story, Masakado made use of several kage-musha, or look-alikes, to keep the troops off his trail. Kikyo no Mae, his lover, however, provided the general with the means to identify the real Masakado--a unique way he had of wrinkling his forehead. In other versions, Masakado is portrayed as a sort of Achilles. His mother, really a dragon, had licked him all over as a baby, making him invulnerable to swords and arrows, except for a single spot on his head or face that she missed. Kikyo betrayed him by informing the general of this chink in his armor.

Even after death, Masakado proved to be a formidable presence. His severed head, placed on public display on the streets of Kyoto, is said to have lifted up and drifted back to the Kanto. Over the centuries Masakado's onryo, or vengeful spirit, has caused untold disasters, including epidemics, earthquakes, floods, famines and numerous sudden unexplainable deaths and illnesses. Masakado legends can be found all over the southern Kanto countryside, and his vengeful spirit is still worshiped in Tokyo at the famous Kanda Myojin Shrine, and at the Kubitsuka in Otemachi, which marks the spot where his head first came to rest.

History of Samurai

female warrior The precursors of samurai emerged in the 10th century as guards at the imperial court in Kyoto and as members of private militias under the control of local warlords. Efforts to create a national conscript army failed and power was decentralized and in the hands of the local daimyos, the most powerful of which had the resources and land to pay the largest militias.

The earliest samurai were essentially privately-equipped mercenaries hired by local lords. Over time they were organized into clans. The samurai era officially began in 1185, when the rival Minamoto and Taira clans fought and the Minamoto clan emerged as the victors. This allowed samurai and daimyo to seize power and relegate the Emperor to shadowy, figurehead status. The Minamoto samurai leader Yorimoto was the first shogun.

From 1185 to 1603, samurai were kept busy fighting battles and protecting their lords and occasionally taking part in an overseas adventures. During the Edo Period (1603-1868), an era of relative peace, they became idle aristocrats at the top of four-level class system. As their power declined, the economic power of the merchant class rose.

Samurai Lifestyle

Samurai didn’t have to work. Their position entitled them to a yearly stipend of rice, which they often sold for cash or other goods. All that was required of them was to be ready to fight and fight when called upon. Some samurai went through their whole lives without ever seeing combat. Some worked at other jobs to supplement their income.

The samurai were at the top of four-tiered class system that included: 1) samurai; 2) farmers; 3) artisans; and 4) merchants. Farmers gave as much as 60 percent of their rice crop to samurai. Artisans often sold their crafts to samurai, some of whom became artisans themselves. Merchants were regarded as te lowest of the low.

Commoners were expected to show respect towards samurai at all times. If a peasant somehow disrespected a samurai — failed to obey an order or accidently touched his sword — the offended samurai had the right to kill the perpetrator on the spot although this rarely happened.

"Battle dress was my pillow, arms my profession" declared a 12th century Japanese hero-warrior. Samurai wore a kimono with a short, loose jacket and long, skirt-like trousers. The top of their head was shaved. The hair on the sides and back was pulled into a pony tail, oiled and folded over the head to form a top knot. The top of head was shaved because that part of the head got very hot and uncomfortable in a Samurai helmet. Before engaging in combat samurai were expected to be well groomed, freshly washed and alert. Some splashed themselves with perfume. When they weren't fighting they sometimes wore an “eboshi” (a hat made from rigid black cloth).

Zen Buddhism and Samurai Spirit

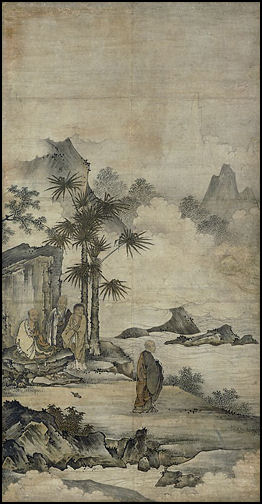

Zen painting Zen Buddhism and the samurai class were closely linked. Zen emphasizes intuitive insight and living for the "here and now." The idea of Zen is not to do something deliberately or with intent, but rather to remove yourself from what you are doing at let "higher forces" guide you. Zen looks down on the use of logic, intellect, idolatry and sacred texts and stresses self-reliance and meditation and emphasizes concrete thought over metaphysical speculation.

The aim of Zen Buddhism is to purify the soul and achieve salvation through inner enlightenment, something that happens for brief instant after 15 or 20 years of meditation. To reach the state of enlightenment, an individuals must unite his or her body and mind with the forces that drive nature. On the journey to enlightenment, Zen Buddhists believe, each level of achievement is just as important as the final state of divinity reached at the end. Zen also emphasizes teachings transmitted from master to disciple rather than a dependance on texts or iconography.

Once Zen Buddhism took hold in Japan had a profound influence on the Japanese. Its austere tone and the simplicity of the doctrine appealed to the military class and artists and was a focal point of samurai culture and art from the 12th century onward. Not only that, Zen Buddhists helped bring Chinese philosophy, especially Neo-Confucianism, to Japan and were involved in commercial endeavors, such as shipping lines, that controlled trade between Japan and China.

Samurai were trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony, which all had Zen overtones. Even swordsmanship and the martial arts were steeped in Zen and ascribed to philosophies that were very esoteric and hard to understand.

Edwin Reischauer wrote in “Japan: Past and Present”: “The anti-scholasticism, the mental discipline—still more the strict physical discipline of the adherents of Zen, which kept their lives very close to nature—all appealed to the warrior caste. . . . Zen contributed much to the development of a toughness of inner fiber and a strength of character which typified the warrior of feudal Japan. “

Samurai Aesthetics

Samurai patronized the arts and engaged in salon-style gatherings hosted by daimyo. They supported painters, poets, and playwrights and often became creators themselves. They arranged flowers, wrote calligraphy, played go and acted in Noh dramas. The tea ceremony was one of their most cherished cultural pursuits. A description of the general Kanamori Yoshishie went: “He defended the castle of Kishiwada and personally took 208 heads. He was also a noted tea master.”

Samurai held elaborate cherry-blossom-viewing parties and wrote poetry about the fragile beauty of cherry blossoms. Many samurai compared their own their to cherry blossoms, which don’t cling to a branch until it withers and falls when they are in their prime.

Samurai were not supposed to engage in urban pursuits like attending kabuki theater and carousing at geisha houses. These were activities associated with low class merchants. Sometimes they dressed in disguise and indulged in urban pleasures that were forbidden to them.

Samurai and the Arts

Zen-style tea ceremony cup According to The Metropolitan Museum of Art: “In contrast with the brutality of their profession, many leaders of the military government became highly cultivated individuals. Some were devoted patrons of Buddhism, especially of the Zen and Jodo schools. Several were known as accomplished poets, and others as talented calligraphers. During the Muromachi period (1392–1573), a number of shoguns exerted a profound cultural influence by amassing impressive collections of painting, enthusiastically supporting No and Kyogen theater, and sponsoring the construction of beautiful temples and gardens in Kyoto. Powerful warriors of the succeeding Momoyama era (1573–1615) inherited this repertoire of interests and added to it a love of grandeur and splendor. [Source: Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The massive walls, vast audience chambers, and soaring keeps of their great castles became the central symbols of the age. Glittering with the abundant use of gold and dynamic in design, the paintings of this period exuded power and monumentality. On a more intimate scale, the development of the tea ceremony was closely intertwined with samurai culture in the late medieval period. During the Edo period (1615–1868), the cult of the warrior, bushido, became formalized and an idealized code of behavior, focusing on fidelity to one’s lord and honor, developed. The samurai of this period inherited the traditional aesthetics and practices of their predecessors and, therefore, continued the seemingly paradoxical relationship between the cultivation of bu and bun—the arts of war and of culture—that characterized Japan’s great warriors.” \^/

Decline of the Samurai

During the Edo Period (1603-1867) samurai were the only people allowed to carry weapons but with no battles to fight their influence diminished. The samurai under the daimyos became impoverished and had to seek other lines of work, such as working as policemen and craftsmen. Many were forced to beg or sell their swords to eat. See Edo Period

Samurai endure in comic books, films. posters and Japanese television dramas. Samurai-style headgear is still worn by Japanese firemen. In the late 2000s it became fashionable for bridegroom to don samurai armors, including a sword, during their wedding ceremony. The armor could be rented from companies that provided it for television dramas.

The samurai spirit is also kept alive in re-creations of famous battles by men dressed in samurai costumes, wielding foam-tipped spears and eye goggles. One of the biggest, at the Ara River in Yorii, commemorates a battle in 1590 involving 50,000 armed soldiers.

The yakuza code of conduct has its roots in the samurai code of conduct. Many Japanese are suspicious of the samurai spirit which they equate with Japanese nationalism and the ideology that got Japan involved in World War II.

Image Sources: 1) Battle reenactments JNTO; 2) armor and sword, Tokyo National Museum and samurai blogs and websites; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016