NINJAS

Ninjas were professional spies, infiltrators and assassins who were valued more for their stealthiness than fighting ability. Their services were used mainly in times of war. There were two main ninja schools: one in Iga Ueno, near Nara, and another in Koga, Shiga Prefecture.

According to the Ninja Museum of Igaryu: “A person who uses Ninjutsu is a ninja. Ninjutsu is not a martial art. Ninjutsu is an independent art of warfare that developed mainly in the regions of Iga in Mie Prefecture, and Koka in Shiga Prefecture, Japan...Most people imagine that ninjas flew through the sky and disappeared, like Superman, waving ninja swords around, sneaking into the enemy ranks and assassinating generals... This is a mistaken image of the ninja introduced by movies and comic books. The jobs of a ninja are divided into the two main categories of performing espionage and strategy. The methodology for performing espionage and strategy is Ninjutsu. Espionage is similar to the job of modern spies, wherein one carefully gathers intelligence about the enemy and analyzes its military strength. [Source: Ninja Museum of Igaryu, Igaueno Tourist Association iganinja.jp ]

“Strategic activities are skills that reduce the enemy’s military power. Ninja did not fight strong enemies by themselves. Ninja fought enemies after they had reduced the enemies’ military power. In times of peace, Ninjutsu was called an art of “entering from afar”, while in times of war, Ninjutsu was called an art of “entering from “nearby”, wherein ninja would constantly gather intelligence concerning the enemy, thinking of ways to beat the enemy, but not fighting the enemy directly. Ninja who thought rationally thought of war by intellect as great, and war by military strength (weapons) as foolish. Therefore, ninja who swing their ninja swords about can be called the lowest of the ninja.”

Prof. Yuji Yamada, 47, an expert on ninjas at Mie University, told the Yomiuri Shimbun. “The most important role of ninja is to collect intelligence. They tried to avoid fighting as much as possible. They were required to have good memories and communication skills first and foremost, rather than physical strength...Ninja insisted on having an existence like a shadow. They accomplished their duties behind the scenes and through unofficial negotiations. They share those characteristics in common with Japanese today.” [Source: Moeko Yoshitomi, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 24, 2015]

Good Websites and Sources: Iga-ryu Ninja Museum site iganinja.jp ; Wikipedia article on Ninjas Wikipedia ; About.com on Ninjas asianhistory.about.com ;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com; NINJA STEALTH, LIFESTYLE, WEAPONS AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTO YORITOMO, GEMPEI WAR AND THE TALE OF HEIKE factsanddetails.com; KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM AND CULTURE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Secrets of the Ninja” by Hiromitsu Kuroi Amazon.com; “Ninja Attack! “ by Matt Alt and Hiroko Yoda. Amazon.com; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior (P.S.)” by John Man Amazon.com; “The Book of Ninja: The Bansenshukai” - Japan's Premier Ninja Manual by Antony Cummins and Yoshie Minam Amazon.com; “Samurai and Ninja: The Real Story Behind the Japanese Warrior Myth that Shatters the Bushido Mystique” by Antony Cummins Amazon.com; Amazon.com; “Samurai: An Illustrated History” by Mitsuo Kure Amazon.com; “Samurai: A History (P.S.)” by John Man Amazon.com; “The Way of the Samurai” (Arcturus Ornate Classics) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com;

Origin of Ninjas

The origins of ninjas is unclear. It is believed that the ancient ninjas may have been yamabushi (“mountain priests”) who adapted the Sonshi, a Chinese martial arts manual, to their own purposes. There are references to ninja-like shonobi in the Asuka Period (592-710) who were used to infiltrate enemy territory and described as "experts in the field of information gathering” and "masters of stealth and disguise."

According to the Ninja Museum of Igaryu: “The roots are found in the “art of warfare” that began around 4000 B.C. in Indian culture, was passed to the Chinese mainland, and around the 6th century, passed through the Korean peninsula and crossed over to Japan.” Sun Tzu, the great Chinese military theoretician, talked the importance and necessity of deception if you want to win in war in the 5th century B.C. It is thought from this belief that the ninja made its way to Japan. In old Japanese fables and stories there are secretive assassin types.

In the Asuka Period, it is said a man name Otomono Sahito, who was used by ruler Shotoku Taishi, gave birth to the first ninjas. “The continental military strategy that was brought from China was developed in conjunction with shugendo, a practice involving mountain training, and adapted to Japan’s extremely hilly, narrow geography, becoming unique Japanese strategy. From this body of strategy emerged Ninjutsu. There were shugen studios in the Iga and Koka regions. Also, the houses of Todaiji and Kofukuji in the Iga region had most of the country’s warriors, and the lords of these houses adopted guerilla-like tactics, and kept the peace by containing one another. From this, Ninjutsu was developed. [Source: Ninja Museum of Igaryu, Igaueno Tourist Association iganinja.jp ]

History of Ninjas

The heyday of the ninjas was between the 12th and 16th centuries, when there were many local wars and the ability to spy, infiltrate and assassinate was highly valued. Hired by warlords as assassins and secret agents, ninja were widely used in the Sengoku period (1467-1568) when Japan was engulfed in civil war

John Man, author of “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior”, told Time magazine: “The height of the ninja was in the 16th century. They’d been evolving. As Japan descended into warlord-ism in the early Middle Ages, the areas where the ninja lived became more and more isolated. As the warlords scrapped over the rest of Japan, Iga and Koka developed their own commune system and self-defense and worked toward sort of a peak of ninja-ism toward the end of the 16th century, at which point their skills had been admired by everyone else, so they were finding employment in the rest of Japan as mercenaries. What happened, as Japan was unified under the great warlord Oda Nobunaga, they could not obviously be tolerated in a unified Japan. And so there were two great invasions of Iga and Koka which finally ended in the late 16th century with the complete takeover of the place and the end of the ninja as they had been for several centuries. [Source: Ishaan Tharoor, Time, February 4, 2013; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior” by John Man, a British travel writer and historian *]

“After 1600 when they became almost redundant, a few of them — some 200 or 300 — were taken on by the shogun as secret police. That’s not enough to give them much of an occupation, so some of them realized that in order for their skills not to be lost, they had better be recorded. Naturally enough, spies being spies, not much was recorded at all. So it was only after they became virtually redundant that they recorded their ways in three or four manuals. That’s really how we come to know anything much about how they actually worked.” *\

During the relative peace of Edo Period ninja found themselves out of work. To survive they began producing manuscripts explaining their skills, weapons and tools. They became the subjects of stories and nobles and this elevated them to the status of magical superheros, an images that persists to this day.

Ninjas, Democracy and Wars

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Ninjas have played important roles in Japanese history. Iga ninja helped Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) escape safely from Osaka in the turmoil that preceded the beginning of the Edo period. Ieyasu showed his gratitude by giving the ninja leader, Hattri Hanzo, a residence in the Imperial Palace, in Edo. The Hanzimon gate at the current palace is named after him. Matsuo Basho, Japan’s most renowned haiku master, may have served for a time amid his nomadic wanderings as a spy for the shogunate.

According to the Ninja Museum of Igaryu: “In the 6th year of Tensei (1578), the ruler of Ise, Kitabatake Nobukatsu (the second son of Oda Nobunaga was adopted by Kitabatake and inherited the reins of the family) planned to attack Iga with Maruyama Castle as base, but retreated in the face of an attack from the troops of Iga. In the 7th year of Tensei (1579), Kitabatake Nobukatsu regrouped and again attacked Iga, but was defeated by the resistance of Iga’s troops. Upon hearing of this (the First Tensei Iga War), Oda Nobunaga was sorely angry, and decided to go to battle himself. In the 9th year of Tensei (1581), he led his 50,000 troops to Iga, burning all of its lands and repeatedly slaughtering adults and children alike. The Iga troops resisted to the end, but a compromise was made, and they submitted. This is the only war in which the Iga region was crippled by attack, and the 800-year manorial system of Iga region was finished, and the ninja were scattered among all lands thereafter (Second Tensei Iga War). [Source: Ninja Museum of Igaryu, Igaueno Tourist Association iganinja.jp ]

Ninja sprung up in proto-democratic communities in Iga and Koka. Man told Time: If you can imagine self-defense communities that needed places to retreat to in case of attack — there are still several dozen, perhaps hundreds of places where they used to gather. These are earth mounds, similar to the Celtic forts in southwestern England. These are not well researched, and the archaeology still has to be done. They are pretty unique to Iga and Koka. They never had the sort of castles that are typical to much of Japan nowadays.” Were these forts defended by armies of ninja? “Nobody knows. The manuals that were written do not talk about cooperative activities at all. They were always treated as individuals. They must have operated as groups, but there’s no records of them doing so.” [Source: Ishaan Tharoor, Time, February 4, 2013; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior” by John Man, a British travel writer and historian]

Iga Ninja

Though Iga was comparatively close to Kyoto, it hosted many exiles on account of its being situated in a basin surrounded by mountains. Among those exiles, there was a clan descendant from Mononobe Uji, as well as peoples who had crossed over, who were skilled in magic and illusions.

Though Iga was comparatively close to Kyoto, it hosted many exiles on account of its being situated in a basin surrounded by mountains. Among those exiles, there was a clan descendant from Mononobe Uji, as well as peoples who had crossed over, who were skilled in magic and illusions.

John Man told Time magazine: Iga is “quite a charming and fairly remote area of rolling hills and forests and valleys and streams and rice paddies — not at all well developed, but very charming. It’s very central in Japan and arose at a time when all of Japan was riven by feuds and governed by warlords. This particular area had been pretty free of warlords and was determined to remain so. And what happened was that the villages there formed themselves like self-defense communes, and it was in that context that the ninja skills developed.” [Source: Ishaan Tharoor, Time, February 4, 2013; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior” by John Man, a British travel writer and historian]

According to the Ninja Museum of Igaryu: “In Iga of the manorial system period, rulers and lords (guardians) did not last long. Because the people of Iga created living areas by manor in units of clans, formed an organized party of landowning farmers, and did not defer to the control of central regimes, an important 12-member council (representatives) was chosen from among the 50-60 members of the party in Iga, and they maintained safety in Iga by cooperation. This is called the “Iga Sokoku Ikki”. [Source: Ninja Museum of Igaryu, Igaueno Tourist Association iganinja.jp ]

The most famous group of Iga ninja is Hattori, Momochi, and Fujibayashi. Hattori Hanzo, Momochi Tambanokami, and Fujibayashi Nagatonokami are the three Iga Ninja Grandmasters. Hattori controlled western Iga. There is a famous person who supported Tokugawa Ieyasu, named Hattori Hanzo Masanari. The Hanzo name was inherited. Momochi controlled southern Iga. The Oe party had originally prospered in the south, and Momochi was one of the supporting families to it, but joining forces with Hattori and riding its wave of strength, Momochi was able to keep its position until the Edo period. Fujibayashi controlled northeastern Iga. Fujibayashi Yasutake, the author of traditional Ninjutsu text “Mansen Shukai” was of this group.

Koga Ninja

Koga-ryu ("School of Koga"; occasionally transliterated as "Koka") is an ancient school of ninjutsu, according to Japanese legend. It originated from the region of Koga (modern Koka City in Shiga Prefecture). Members of the Koga school of shinobi (ninja) are trained in disguise, escape, concealment, explosives, medicines and poison; moreover, they are experts in techniques of unarmed combat (Taijutsu) and in the use of various weapons. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The beginnings of the Koka-ryu may be traced to near the end of the Muromachi period. While the town of Koka was under the jurisdiction of the Rokkaku clan, it was a kind of autonomous municipality composed of peasant unions. Sasaki Rokkaku of Omi Province, using Kannonji Castle as a base, started to steadily build up military might. He made light of commands from the Ashikaga shogunate, and eventually began to ignore the shogunate altogether. In 1487, General Ashikaga Yoshihisa brought with him an army to stamp out this rebellion, and a battle between Ashikaga and Rokkaku’s camps ensued. Rokkaku leaders were captured but managed escape and ordered the Koka warriors to guerrilla tactics against the shogun’s forces. Exploiting their geographical advantage in the mountains, the Koka warriors launched a wide range of surprise attacks against Ashikaga’s forces, and tormented them by using fire and smoke on Ashikaga’s camp during the night. The guerrilla warfare prevented a final showdown, until Ashikaga died in battle in 1489, ending the three-year conflict and sparing the lives of the Rokkaku duo. +

The elusive and effective guerrilla warfare used by the Koka warriors became well known throughout the whole country. This also marked the first time that the ninja of Koka were drafted as a regular army by their lord. Previously, they were only mercenaries and it was not uncommon to have warriors from Koka on both sides of a battle. As a result of this victory, the local samurai in the 53 families who participated in this battle were called "the 53 families of Koka". +

Ninja Books and Names

Picture of a weapon from a ninja manual

Among existing traditional Ninjutsu books, “Mansen Shukai”, “Shoninki”, and “Shinobi Hiden” are regarded a the Three Great Books of Ninjutsu. 1) Mansen Shukai, by Fujibayashi Yasutake, integrated Iga and Koka Ninjutsu, and a few types of copies are passed down in both Iga and Koka. 2) Shoninki, by Fujibayashi Masatake, is a traditional text of the Kishu-ryu 3) Shinobi Hiden, by Hattori Hanzo is a traditional text of Iga and Koka. [Source: Ninja Museum of Igaryu, Igaueno Tourist Association iganinja.jp]

Many books related to ninja were written in the Edo Period. Before it is believed many traditions were handed down orally. It is assumed that the books were written to pass on traditions and commit them to record. The are traditional texts in which the words “there is an oral tradition” stand out, and this may indicate that oral tradition was of greater importance.

John Man told Time magazine: “ Ninja comes originally from the Chinese and is a vague Japanese pronunciation for “one who endures.” And because Japanese is what it is, there is also a Japanese word which means the same thing: shinobi. They are interchangeable. Because Chinese always was a slightly more higher-status way of talking, ninja tends to be higher status, and became acceptable to foreigners. Shinobi remains the Japanese way of talking about them. [Source: Ishaan Tharoor, Time, February 4, 2013; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior” by John Man, a British travel writer and historian]

Different names for ninja have been used in different places and at different times. In the Asuka Era they were called Shinobi. In the Nara Era they were called Ukami. In the Sengoku Era they were called Kanja and Rappa. In the Edo Era they were called Onmitsu. In the Taisho Era they were called Ninjyutsusha or Ninsya.

Names by region: 1) Kyoto and Nara: Suppa, Ukami, Dakkou; 2) Yamanashi: Suppa, Suppa, Mitsu-no-mono Suppa; 3) Niigata, Toyama: Nokizaru, Kanshi, Kikimonoyaku; 4) Miyagi: Kurohabaki; 5) Aomori: Hayamichi-no-mono,Shinobi; 6) Kanagawa: Kusa, Monomi, Rappa; 7) Fukui: Shinobi. There are many other names in the different regions, but the above are the most representative. There are various ways to call ninja, depending on their relation to being secretive, the jobs they performed, and the reading of the Chinese characters with which their names are written.

Ninja, Samurai and Assassins

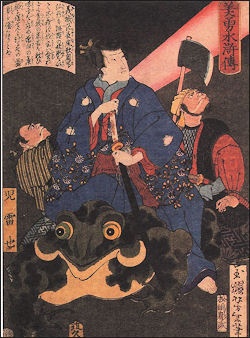

Famous samurai Miyamoto Musashi slashing a tengu (a mythical creature)

John Man told Time magazine: “Ninja are usually regarded as the anti-samurai. The samurai were extremely overt and colorful personalities. Their whole being depended on public display — death-defying and often death-seeking bravado. The ninja were the opposite: in order to be a spy, you have to survive and be secretive. Secretiveness was something the samurai pretended to despise, but in fact the ninja were vital to military activity. And quite often the samurai during the day doubled as ninja during the night.” So could ninja be samurai at the same time? “You could, theoretically. There would have been some sort of distinction, because samurai were often extremely high class, but ninja not necessarily so. But there was an overlap in the middle. [Source: Ishaan Tharoor, Time, February 4, 2013; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior” by John Man, a British travel writer and historian *]

“On whether ninja were similar to other secretive, cult-like orders like the hashishin, or assassins of the Crusades, Man said, “I don’t think so, because the assassins had a strong, powerful jihadist sense, very deeply rooted in the religion, whereas the ninja were not religiously driven. The overlap came in that the ninja wanted what was called “right-mindedness.” They had to have the correct attitude in order to undertake what they did in defense of their villages, their masters and themselves. What they did was train in a local belief system, which was Shinto and called shugendo, which is really mountain asceticism, which demanded that you undertake training in the mountains and along the streams to hone your body and mind until you are absolutely fit enough to carry out ninja activities.”

There were ninja families, clans and bloodlines. Man said: “Yes, you were born into it, and you were probably a landowner or working those fields, fixed to a particular estate. Loyalty would have tied you to an area and your family. It was very feudal.”

Ninja and Popular Culture

Ninja sikiruki

On how did the ninja legend spread around the world, John Man told Time magazine: “It took on a life of its own very much in the 19th century in Japan and then spread to the West, but really after the Second World War. I blame James Bond, really. The Bond movie You Only Live Twice really popularized the idea of ninja among people who are not interested in martial arts. It’s quite strange, really: the idea of the ninja spread, but in the film they’re not represented as ninja at all, more as commandos. Nevertheless, that’s what made the term popular in the West. Of course, there is a whole martial-arts community that’s separate from that tradition and has a life of its own. [Source: Ishaan Tharoor, Time, February 4, 2013; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior” by John Man *]

“By the 19th century there were prints of dark-robed men stealing over castle walls. Yes, there were some prints that were in operation. The myths that had been assiduously cultivated really spread only after [the ninja heyday], as it became ever more removed from reality. When I started this book, I thought I was going to be involved in all sorts of nonsense which is currently believed about ninja. But I was absolutely delighted to realize there was a historical core to them. And that’s really what the book is about. And even though ninjitsu is considered a martial art, there is very little to do that in the way of authenticity. *\

“You look up ninja websites and ninja books and there are titles about the art of invisibility or how to disappear, which has been invented largely since 1945 in order to create and sustain a ninja community, many of whom dispute among themselves what is meant by true ninja-ism and what is authentic. There are masters still in existence who claim to have scrolls that go back to the Middle Ages granting them all sorts of authenticity down the generations, but nobody has seen these scrolls or proved anything about them. *\

Ninja Myths

Ishaan Tharoor wrote in Time: Ninja are everywhere in popular culture — they slice up mobsters in movies and fruit on your iPhone. We seem to think it makes sense to compare them to pirates and then think of them fondly as adolescent mutant turtles living in a New York City sewer with a kimono-clad rat.” Man, addressed some of the myths. [Source: Ishaan Tharoor, Time, February 4, 2013; “Ninja: 1,000 Years of the Shadow Warrior” by John Man, a British travel writer and historian *]

ninja tourists

What do you think our most major misconception about the ninja is? John Man: “I had thought they would be assassins or would-be killers, but I was surprised that they had a spiritual dimension and that shugendo was an important part of the training. Even now, the experts in ninjitsu tell you that right-mindedness was a prime element of their training.” *\

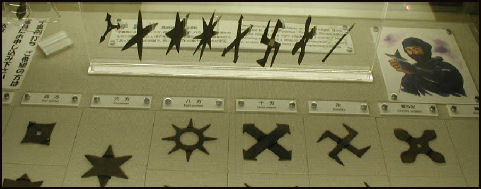

Did ninja have special weapons? “In the many weapons that are displayed in the ninja museums, first there was an awful lot of adapted farm equipment, and secondly none of it’s authentic. It was all made long after the ninja became redundant.” *\

What about the tales of ninja as magicians? “There was a folk tradition of magical belief that if you write certain things, certain statements on bits of paper and put them in the right place in a room, then magical things would happen. But these are in the manuals which come after the event.” *\ On the book “Ninja Attack!” by Matt Alt and Hiroko Yoda, Roland Kelts wrote they “turn their lucid lenses to the myths and realities behind Japan’s irresistible secret agents, spies. Revealing what true ninja actually wore (not the sleek black uniforms and masks of popular rendering, of course, because they tried to blend into their surroundings — duh), ate, brandished and so on, the book admirably balances the seductions of ninja fiction with the astonishments of historical truth."

Academic Study of Ninja

Mie University in Tsu puts emphasis on the academic study of ninja, with the aim of unraveling their roles and lifestyles while dispelling the image created by films and manga. Prof. Yuji Yamada teaches a “Ninja Study” class. [Source: Moeko Yoshitomi, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 24, 2015 ***]

Moeko Yoshitomi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun, “Yamada, an expert of Japanese medieval history, began studying ninja in early 2012 at the request of the university. As there are few academic papers on ninja, he initially thought academically studying them would be difficult as ninja skills have mostly been handed down by word of mouth. However, once he began carefully researching books on ninja at the Ninja Museum of Igaryu, he gradually learned what ninja were really like. These books are not open to the public. ***

“The Ninja Study class began at the university in the 2013 school year. In the last and current school year, 230 students took the class after winning a lottery. More than 400 students applied to join the class. Jinichi Kawakami, 65, also teaches the class elements such as walking stealthily and a breathing method to prevent runners from tiring. Kawakami mastered the Koga-ryu ninja skills.This school year, a similar ninja lecture was also given twice at Mie Terrace, a promotion base of the prefecture in Tokyo, to a packed audience of 70 people per lecture.” ***

shuriken, ninja stars

Nakano Spy School: a Ninja Legacy?

The Nakano School was the primary training center for military intelligence operations by the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. In July 1938, after a number of attempts to penetrate the military of the Soviet Union had failed, and efforts to recruit White Russian had failed, Army leadership felt that a more "systematic" approach to the training of intelligence operatives was required. The Nakano School was initially focused on Russia, teaching primarily Russian as a foreign language. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, and the start of World War II, the Nakano School changed its focus to southern targets. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The Imperial Japanese Army had always placed a high priority on the use of unconventional military tactics. From before the time of the First Sino-Japanese War, Japanese operatives, posing as businessmen, Buddhist missionaries in China, Manchuria and Russia established detailed intelligence networks for production of maps, recruiting local support, and gathering information on opposing forces. Japanese spies would often seek to be recruited as personal servants to foreign officers or as ordinary laborers for construction projects on foreign military works. +

A small school, over its history, the Nakano School had over 2500 graduates, who were trained in a variety of subject matters related to counterintelligence, military intelligence, covert operations, sabotage, foreign languages, and aikido, along with unconventional military techniques in general such as guerrilla warfare. Extended courses were provided on a wide variety of topics including philosophy, history, current events, martial arts, propaganda, and various facets of covert action. +

While small, its graduates occasionally had dramatic successes, such as the intact capture of oil facilities in Palembang, Netherlands East Indies, by Nakano School-trained paratroopers. Nakano graduates were also very active in Burma, India, and Okinawa campaigns. F Kikan, I Kikan and Minami Kikan(ja) were heavily staffed with Nakano graduates. F- Kikan and I Kikan were directed against British India, and was instrumental in forming the Indian National Army and supporting the Azad Hind movement in Japanese-occupied Malaya and Singapore. It also worked with Indonesian nationalists seeking the independence of the Netherlands East Indies. Its efforts to promote anti-British and anti-Dutch movements lasted past the end of the war, and played a role in the independence of India and Indonesia. +

Minami Kikan supplied and led the Burmese National Army to engage in anti-British subversion, intelligence-gathering and later direct combat against British forces in Burma.

fighting with a sickle

In China, one Nakano School operation was the unsuccessful attempt to weaken China's Nationalist government by introducing large quantities of forged Chinese currency using stolen printing plates from Hong Kong. Towards the end of the war, graduates of the Nakano School expanded their activities within Japan itself, where their training in guerilla warfare were needed to help organize civilian resistance against the prospective American invasion of the Japanese home islands. +

Image Sources: Ninja Museum Iga Ueno; Wikimedia Commons Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016