MUSASHI AND OTHER FAMOUS SAMURAI

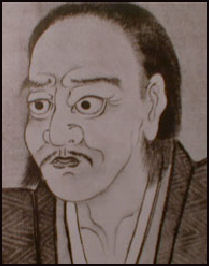

Musashi One of the most famous samurai was Miyamoto Musashi (1584-1645). He wrote a famous text on swordsmanship (“A Book of Five Rings”) and reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday. He got into his first duel when he was 12 and killed an accomplished swordsman using only a wooden staff. Later victims included the famed swordsman, Demon of the Western Provinces. In his treatise he broke samurai convention by declaring, “the true Way of swordsmanship is to fight with your opponent and win.”

Musashi lived at a time when the Warring States period (1467-1586) was giving way to the more peaceful Edo period (1603-1867). He participated in the Battle of Sekigahara between the Tokugawa and Toyotmi clans as a foot soldier but failed to distinguish himself on the battlefield. His reputation as a great swordsman was earned by traveling the country and beating a variety of famed marital artists in duels.

Records show that later in life Musashi began pursuing more philosophical and spiritual matters, which earned him the title “sword saint.” “Book of Five Rings” was completed shortly before his death. Like Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” it is widely read by businessmen and political leader for advise on getting ahead and defeating rivals. Musashi also left behind paintings and other art objects, some of which have been designated as national important cultural properties.

Other famous samurai included Date Masmune was the leader of the Date clan in Tokuko in northern Honshu in Warring States (1493-1573). He was known as the one-eyed dragon. In the late 2000s he became a central character in the popular video game “Sengoku Basara “. Honda Tadakatsu, a retainer for Tokugawa Iyesu is said to have fought in 57 battles without suffering a scratch.

Some samurai identified with insects such as praying mantises and dragonflies and placed images of these creatures on their helmets. Some samurai believed that human soul dwelled in butterflies.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; NINJAS IN JAPAN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; NINJA STEALTH, LIFESTYLE, WEAPONS AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; WOKOU: JAPANESE PIRATES factsanddetails.com; MINAMOTO YORITOMO, GEMPEI WAR AND THE TALE OF HEIKE factsanddetails.com; KAMAKURA PERIOD (1185-1333) factsanddetails.com; BUDDHISM AND CULTURE IN THE KAMAKURA PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on the Samurai Era in Japan: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Samurai Women on About.com asianhistory.about.com ; Samurai Armor, Weapons, Swords and Castles Japanese Swords Blade Diagrams ksky.ne.jp ; Making the Blades www.metmuseum.org ; Wikipedia article wikipedia.org ; Putting on Armor chiba-muse.or.jp ; Castles of Japan pages.ca.inter.net ; Enthusiasts for Visiting Japanese Castles (good photos but a lot of text in Japanese shirofan.com ; Seppuku Wikipedia article on Seppuku Wikipedia ; Tale of 47 Loyal Samurai High School Student Project eonet.ne.jp/~chushingura and Columbia University site columbia.edu/~hds2/chushinguranew : Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; Kojiki, Nihongi and Sacred Shinto Texts sacred-texts.com ; Imperial Household Agency kunaicho.go.jp/eindex; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com ; Samurai scholar: Karl Friday at the University of Georgia.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Book of Five Rings” by Miyamoto Musashi Amazon.com; “Musashi” , a novel about the legendary swordsman by Eiji Yoshikawa. (1995) Amazon.com; “The Lone Samurai: The Life of Miyamoto Musashi” by William Scott Wilson Amazon.com; “Samurai and Ninja: The Real Story Behind the Japanese Warrior Myth that Shatters the Bushido Mystique” by Antony Cummins Amazon.com; “Vagabond”, a popular 27-volume manga based on “Miyamoto Musashi” by the famous mangaka Takehiro Inoue Amazon.com; “The Samurai Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Guide to Japan's Elite Warrior Class” by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “A History of the Samurai: Legendary Warriors of Japan” by Jonathan Lopez-Vera and Russell Calvert Amazon.com; “Samurai: An Illustrated History” by Mitsuo Kure Amazon.com; “An Illustrated Guide to Samurai History and Culture: From the Age of Musashi to Contemporary Pop Culture” by Gavin Blair and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “Samurai: A History (P.S.)” by John Man Amazon.com; “The Way of the Samurai” (Arcturus Ornate Classics) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com; “Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan” (1899) by Inazo Nitobe, inspired by film “Last Samurai” Amazon.com; “Shogun & Daimyo: Military Dictators of Samurai Japan” by Tadashi Ehara Amazon.com; Films: “Seven Samurai” Amazon.com and “Throne of Blood” Amazon.com; by Akira Kurosawa; “The Last Samurai” with Tom Cruise Amazon.com; ; “Twilight of a Samurai” Amazon.com; , nominated for an Academy Award in 2004

Taira no Masakado, the First Samurai?

Taira no Masakado

The great folk hero Taira no Masakado is sometimes referred to as the first samurai. A 10th century historic figure, he is famous throughout Japan as a rebel who challenged the Imperial Court, and as perhaps the scariest ghost that ever haunted the land. Heir to a great family fortune, Masakado was also a charismatic leader and skilled field general, which he proved time and time again in successful military campaigns against other local chieftains. [Source: Kevin Short, Yomiuri Shimbun, September 8, 2011]

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri Shimbun, “In those days, Japan was ruled by the Emperor in Kyoto, with official magistrates sent out to govern and collect taxes in outlying provinces such as the Kanto. Masakado, on one of his military forays, got a bit carried away. He attacked the local government compounds, and eventually declared himself emperor of eastern Japan.”

“Naturally, the Imperial Court could not tolerate such an affront to its sovereignty, and quickly dispatched troops to hunt the rebel down. Masakado, however, was operating on his own turf, and proved to be elusive prey. Official history books assert that eventually he was killed in a pitched battle with the government troops, but local legends hold that he was betrayed by his wife.

In one version of this story, Masakado made use of several kage-musha, or look-alikes, to keep the troops off his trail. Kikyo no Mae, his lover, however, provided the general with the means to identify the real Masakado--a unique way he had of wrinkling his forehead. In other versions, Masakado is portrayed as a sort of Achilles. His mother, really a dragon, had licked him all over as a baby, making him invulnerable to swords and arrows, except for a single spot on his head or face that she missed. Kikyo betrayed him by informing the general of this chink in his armor.

Even after death, Masakado proved to be a formidable presence. His severed head, placed on public display on the streets of Kyoto, is said to have lifted up and drifted back to the Kanto. Over the centuries Masakado's onryo, or vengeful spirit, has caused untold disasters, including epidemics, earthquakes, floods, famines and numerous sudden unexplainable deaths and illnesses. Masakado legends can be found all over the southern Kanto countryside, and his vengeful spirit is still worshiped in Tokyo at the famous Kanda Myojin Shrine, and at the Kubitsuka in Otemachi, which marks the spot where his head first came to rest.

Minamoto Yoshiie

Minamoto Yoshiie

Minamoto Yoshiie (1041-1108) was arguably the first samurai or at least an early inspiration for them. F.W. Seal wrote in Samurai Archives: “Minamoto Yoshiie, a man who came to embody the spirit of the samurai and a legend even in his own time, was the son of Minamoto Yoriyoshi. Yoriyoshi, the third generation of the Seiwa Genji, was a noted commander, and in 1051 was commissioned to defeat the rebellious Abe family of Dewa. The Abe had for years held prominent posts in this distant, forbidding region, and had come to enjoy a near autonomous existence. Like Taira Masakado, the Abe had been tasked with subduing the northern barbarians, and, from the Court’s point of view and over time, become barbarians themselves. [Source: F.W. Seal, Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

Shrouded in mystery, elevated to an almost godlike status in the old chronicles, it is difficult to place Minamoto Yoshiie in a historical context. His greatest political contribution was probably in strengthening the Minamoto family, especially those branches residing in the Kanto. His other contribution was less tangible. The legend of Minamoto Yoshiie, who emerged from his northern wars and the chronicles as a cultured man of war, established a model for future samurai that would influence generations of warriors to come.” |~|

Minamoto Yoshiie Versus Abe Yoritoki

F.W. Seal wrote in Samurai Archives: “Yoriyoshi’s chief opponent was Abe Yoritoki, an unscrupulous character who died of an arrow wound in 1057. By this point in the so-called Former Nine-Years War, Yoriyoshi’s son Yoshiie had joined the expedition. A promising young warrior, Yoshiie participated in the Battle of Kawasaki (later in 1057) against Yoritoki’s heir Sadato. In a snowstorm, the Minamoto assaulted Sadato’s stronghold at Kawasaki and were driven back; in the course of the hard-fought retreat Yoshiie distinguished himself and earned the nickname 'Hachimantaro', or 'First son (or First born) of the God of War (Hachiman)'. Abe Sadato comes across as an altogether more impressive man than his father, and proved a formidable foe even for Yoshiie and Yoriyoshi. Yet the Minamoto cause was much assisted by the enlistment of Kiyowara Noritake, a locally powerful figure whose rugged northern men swelled Yoriyoshi’s ranks. [Source: F.W. Seal, Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

Minamoto Yoshiie

“In 1057 the fighting culminated in a series of actions that further enhanced Yoshiie’s reputation. Sadato had attacked the Minamoto troops but suffering a reverse retreated into a fort by the Koromo River. Yoriyoshi ordered a spirit assault on the fort, which Sadato was forced to flee. During the chaotic retreat, Yoshiie was supposed to have chased Sadato and had an impromptu renga (linked verse) session with his enemy from horseback, afterwards allowing him to escape, as related in the Mutsu Waki...'Yoriyoshi’s first son, Hachiman Taro, gave hot pursuit along the Koromo River and called out, "Sir, you show your back to your enemy! Aren't you ashamed? Turn around a minute, I have something to tell you." When Sadato turned around, Yoshiie said: “Koromo Castle has been destroyed. [The warps in your robe have come undone]” Sadato relaxed his reins somewhat and, turning his helmeted head, followed that with: “over the years its threads became tangled, and this pains me.” Hearing this, Yoshiie put away the arrow he had readied to shoot, and returned to his camp. In the midst of such a savage battle, that was a gentlemanly thing to do. |~|

“The likelihood that this incident actually occurred is probably nil but it made Yoshiie seem all the more colorful, and gave him an opponent worthy in both warfare and culture. Tales like these laid the groundwork for the samurai mystique, and provided young warriors with ready-made role models and measures against which to test their own prowess and bravery. |~|

“Yoshiie may have spared his noble opponent, but the war was nearly over. Sadato continued his flight until he reached one of his remaining forts, this one on the Kuriyagawa, and prepared for another stand. The government troops arrived and after a few days of fighting brought the fort down. Sadato and his son died, and his brother Muneto was captured. Yoshiie gave thanks to his (nick)namesake by establishing the Tsurugaoka Hachiman shrine near Kamakura on the way back to Kyoto. Yoriyoshi was awarded the governorship of Iyo for his services against the Abe while Yoshiie was named Governor of Mutsu. Interestingly, Abe Muneto was released into the custody of the Minamoto and lived in Iyo, becoming a companion of Yoshiie’s. In 1082 Yoriyoshi died.” |~|

Achievements of Minamoto Yoshiie

Minamoto Yoshiie at Nakoso Barrier

F.W. Seal wrote in Samurai Archives: “In 1083 Yoshiie was commissioned by the Court to subdue another rebel, this time against the same Kiyowara family who had assisted the Minamoto in the previous war. After the Abe’s defeat, the Kiyowara had been elevated and filled the power vacuum in the north. A power struggle had broken out among various family members, and in the end Yoshiie was sent to quell the disturbance. The conflict became known as the Later Three-Year War and culminated, after a setback at Numu (1086), in the Battle of Kanazawa. In an incident that became a famous military anecdote, Yoshiie’s men were advancing to contact when a flock of birds began to settle in a certain spot then abruptly flew off. Yoshiie suspected an ambush and had the place surrounded, sure enough revealing the enemy army. [Source: F.W. Seal, Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

“Yoshiie went on to reduce Kanazawa through siege and the Later Three-Year War drew to a close. The Court was pleased that the Kiyowara had been suppressed, but viewed the conflict as outside the Court’s responsibility, as technically Yoshiie had not been commissioned by the emperor to fight. This meant that no rewards would be distributed to Yoshiie’s men, an unfortunate situation Yoshiie remedied by paying them himself with his own lands. This action greatly enhanced Yoshiie’s reputation and also secured lasting bonds of loyalty for the Minamoto in the Kanto region, bonds that would pay dividends in the following century. |~|

“Stinginess aside, the aristocracy held Yoshiie in near-awe, and Fujiwara Munetada dubbed him 'The Samurai of the greatest bravery under heaven.' At the same time, the Court kept Yoshiie at arm’s length. It did go so far as permitting Yoshiie to visit the Imperial Court in 1098; a rare honor that by it’s very rareness indicates the widening gulf between the Court and provincial houses. This alienation would in the end contribute to the eclipse of Imperial authority by the samurai in the later 12th Century.” |~|

Minamoto Yoritomo

Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147- 1199) is one of the major figures in Japanese history. The founder of the first of the three shogunates (bakufu, military governments) in Japanese history, he took firm control of Japan, established a military government in Kamakura and persuaded the Emperor to give him the hereditary title of shogun. He established the first hereditary shogunate near present-day Tokyo in city Kamakura while the emperor remained in isolation in Kyoto. Yorimoto purged members of his own family to firm his grip on power.

Minamoto Yoritomo was a member of the Minamoto clan (Genji clan) which had seized power of Japan in 1195 after the Gempei War. The Minamoto clan was a major military family, which frequently clashed with the Taira clan (Heike clan), the other major military family, in the 12th century.

Yorimoto was the third son of a clan leader — Minamoto no Yoshitomo — who was killed along with many family members and allies after the Minamotos were defeated by the rival Taira clan in the Heiji Rebellion of 1159. Minamoto Yoritomo spent his youth in a Buddhist temple. When he was old enough he began gathering allies an set up his base in Kamakura, which was far from the government seat in Kyoto and close to many of his allies.

According to Samurai Archives: “In the Heiji Rebellion of 1159, Yoritomo was captured. As he was just a child he was exiled to Izu province. He married Hôjô Masako, a woman from an important local family. (After the death of Yoritomo, her family controlled the shogunate.) In 1180 he obtained an order from Prince Mochihito, a son of Emperor Go-Shirakawa, ordering him to raise troops and chastise the Taira. He called the Minamoto to his banner and established himself in Kamakura in the Kanto. The men who came to him were called his "house men" (gokenin), and they were in effect retainers, or vassals, who owed loyalty directly to him. Even that year he set up a Board of Retainers (samurai dokoro ) to control his retainers. [Source: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

Minamoto Yoritomo Takes Over Japan

Minamoto Yoritomo

Minamoto claimed Japan after defeating the Taira clan in a series of battles. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “With the defeat of the Taira in 1185 and his appointment as shogun by the imperial court in 1192,Minamoto Yoritomo (1147-1199) became Japan’s "de facto" military and political leader. Although the Emperor in Kyoto retained prestige and legitimacy, Yoritomo and his shogunate ("bakufu") in Kamakura established mechanisms for ruling Japan within the shell of the dysfunctional imperial state. The most important offices created by Yoritomo were the "jitō" (stewards) and "hugo" (military governors), vassals who were appointed to maintain order on estates and in regions across Japan.” [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

According to Samurai Archives: “The Genpei War Yoritomo sent armies against the Taira headed by his cousin Minamoto no Yoshinaka (Kiso Yoshinaka) and his younger brother Minamoto no Yoshitsune. (The story of the relationship between the brothers is one of the most famous in Japanese history.) They were successful in defeating the Taira, but part way through Yoritomo ordered Yoshitsune to destroy Yoshinaka on the grounds that his troops were misbehaving in Kyoto. By this victory, Yoritomo effectively controlled most of the country. Probably remembering his own history, he made sure (almost) none of the Heike survived. [Source: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

“In 1185 ordered Yoshitsune’s arrest on the grounds he had received favors directly from the court, though he was a retainer of his brother. When Yoshitsune fled with a handful of men, Yoritomo ordered a massive manhunt for him throughout the whole country. At that time most of the country was divided into estates which were the source of revenue for the central government (kôryô ) or, especially, private individuals (shôen). |~|

“To make it possible for him to find these few people, Yoritomo obtained an imperial receipt that allowed him to place his own retainers as stewards (jitô ) in most of the estates, giving him effective control over most of the land in the country. He also levied a small tax (hyôrômai ) on estates of all categories, including "tax free" estates. He also placed "protectors" (shugo ) in each province to ferret out evildoers. (These shugo were the forerunners of the daimyo.) Yoshitsune, who had sought refuge with the Fujiwara of Mutsu province was killed by Fujiwara no Yasuhira in 1189, but despite this Yoritomo attacked and conquered the province later that year, extending his rule over this northern territory also.”|~|

Yorimoto as Shogun

Minamoto no Yoritomo

Once Minamoto Yoritomo had consolidated his power, he established a new government at his family home in Kamakura. He called his government a Shogunate (tent government), but because he was given the title seii taishogun by the emperor, the government is often referred to in Western literature as the shogunate. Yoritomo followed the Fujiwara form of house government and had an administrative board, a board of retainers, and a board of inquiry. After confiscating Taira estates in central and western Japan, he had the imperial court appoint stewards for the estates and constables for the provinces. [Source: Library of Congress*]

As shogun, Yoritomo was both the steward and the constable general. The Kamakura Shogunate was not a national regime, however, and although it controlled large tracts of land, there was strong resistance to the stewards. The regime continued warfare against the Fujiwara in the north, but never brought either the north or the west under complete military control. The old court resided in Kyoto, continuing to hold the land over which it had jurisdiction, while newly organized military families were attracted to Kamakura. *

According to Samurai Archives: Yoritomo did not take over the imperial government, but it gave him authority for his doing whatever he wanted to do, and his government through control of his own retainers was the only effective government in Japan. His Board of Inquiry (monchûjo ), which had a pretty good reputation for fairness, was used and accepted by even those not his retainers. Yoritomo accepted a number of comparatively low court ranks, including that of "Barbarian-expelling Generalissimo" Seii Tai Shogun (1192). By this he was formally delegated with the emperor’s military authority. [Source: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com |~|]

Thomas Hoover wrote in “Zen Culture”: The form of government Yoritomo instituted is generally, if somewhat inaccurately, described as feudalism. The provincial warrior families managed estates worked by peasants whose role was similar to that of the European serfs of the same period. The estate-owning barons were mounted warriors, new figures in Japanese history, who protected their lands and their family honor much as did the European knights. But instead of glorifying chivalry and maidenly honor, they respected the rules of battle and noble death. Among the fiercest fighters the world has seen, they were masters of personal combat, horsemanship, archery, and the way of the sword. Their principles were fearlessness, loyalty, honor, personal integrity, and contempt for material wealth. They became known as samurai, and they were the men whose swords were ruled by Zen. [Source : “Zen Culture” by Thomas Hoover, Random House, 1977]

Document 14 of the Kamakura Bakufu — Yoritomo Settles a Dispute over the Possession of a Jitō Shiki, ordered: to Taira Michitaka, 3d year of Bunji [1187], 5th month, 9th day — reads: “That the false claim of Bingo Provisional Governor [“gon no kami”] Takatsune is denied; and that the “jitō shiki “of Sonezaki and Sakai Befu’s Yukitake Myō, within Kii District, Hizen Province, is confirmed. Because of the dispute between Takatsune and Michitaka over the aforesaid places, the relative merits of the two parties have been investigated and judged, and Michitaka’s case has been found justified. He shall forthwith be confirmed as “jitō”. However, as concerns the stipulated taxes [“shotō”] and the annual rice levey [“nengu”], [the “jitō”’s] authority, following precedent, shall be subject to the orders of the priprietor [“honjo no gechi”]. It is recorded in Michitaka’s documentary evidence [“shōmon”] that originally these places were Heike lands. Therefore, in the pattern of confiscated holdings [“mokkan”], management should proceed accordingly. It is commanded thus. Residents shall know this and abide by it. Wherefore, this order.” [Source: “The Kamakura Bakufu: A Study in Documents,” by Jeffrey P. Mass (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1976), 40, 49 158]

Mass Suicide of 380 Samurai and the Battle of Sekigahara

On August 1, 1600, a fire was set inside the castle, perhaps by a ninja. Some of Mitsunari's soldiers managed to enter the castle and surround the 380 samurai. Rather than give up Mototada order his enemies to chop of his head, which they in full view of the 380 samurai, who then followed their leader's example and committed seppuku (ritual suicide).

The fall of Fushimi encouraged other leaders to join Mitsunari. Their combined force met Ieyasu's army on September 15 at Sekigahara, 60 miles northwest of Kyoto

The Battle of Sekigahara on October 21, 1600 is one of the most important battles in Japanese history. The Eastern Army of Ieyasu faced off against the Western Army of Mitsunari. Each army contained more than 80,000 men.

The Eastern Army of Ieyasu routed the Western Army of Mitsunari, paving the way for Ieyasu to claim the Shogunate. Ieyasu won the day by employing some underhanded trickery. He convinced a Western Army general to switch sides at the last minutes. Samurai under the general’s command attacked the Western Army from the rear, causing it to fragment and open itself to attacks from the Eastern Army.

Today a plinth marks the spot where Ieyasu’s generals presented him with thousands of heads. Three years later Ieyasu was given the title of shogun.

Battle of Sekigahara

Tale of the 47 Ronin

One of the most famous events in Japanese history was the mass suicide of 47 samurai in 1702. Known as the “Tale of the 47 Loyal Assassin” or “Churshingura”, it has been the subject of many “kabuki” dramas, “bunkara” puppet theaters, children's books, bestselling novels, movies and television mini-series and documentaries.

“The Tale of the 47 Rônin” is based on the play “ Chûshingura: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers,” which was written in 1748 for puppet theater based on the historical event called the Ako Incident . This version of the story has influenced all later retellings. The play is available, as translated by Donald Keene, from Columbia University Press. [Source:Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “During the stillness of the night of January 30, 1703, forty-six masterless samurai (rônin) burst into the Edo mansion of a government official, Lord Kira, killed him, and took his head to the grave of their former master Lord Asano in proof that they had avenged his death. Lord Kira had, nearly two years earlier, goaded their young Lord Asano into misbehavior for which he had been condemned to die. His loyal former retainers secretly plotted and finally successfully executed their revenge. As a mark of respect for their loyalty, the government allowed the rônin — sentenced to death for the killing — to commit suicide rather than submit to execution.”

Sawa Kurotani wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: The Ako incident in 1703, in which the former retainers of the Ako clan avenged their lord’s unjust death, marked an important moment in which the roles of samurai shifted from professional warriors to bureaucrats and administrators. The former Ako retainers' adherence to the outdated code of conduct and obsolete wartime ethos has solicited popular sympathy ever since its first theatrical adaptation in the late Edo period, but gained new significance in the 1960s and '70s when the old was rapidly replaced by the new. [Source: Sawa Kurotani, Daily Yomiuri, December 27, 2011]

47 Rônin Story

The series of events that led to the mass suicide began when Kira Kozukenosuke, an evil warlord and senior official in the Tokugawa shogunate, picked a fight with a daimyo named Asano, who grazed the forehead of Kira with his sword in a fit of anger in a corridor of Edo castle. Such an act was strictly forbidden in the castle and Asano was forced to commit suicide or be killed by Kira's men, depending on the version of the story. Knowing the Asano's death would probably be avenged Kira fortified the walls of his castle and tripled the number of men protecting it.

Ronin Enter Sengakuji Temple to pay homage to their lord

Forty-seven samurai loyal to Asano vowed to get revenge but they waited for two years and acted like drunken fools, ignoring their wives and children and even failing to show up for the burial of Asano, during that time to make Kira think they were too consumed in drowning their sorrows to be concerned with revenge.

On December 14, 1702, the 47 samurai broke into Kira's Tokyo fortress. Clad in a black-ninja suits with white trim, they approached the castle, running over snow barefoot to remain quiet, and cut up the defenders of the fortress with their tempered steel swords. [Source: T.R. Reid, the Washington Post]

Kira was captured in an outhouse, and beheaded. After marching through the streets of their hometown before cheering crowd, with Kira's head, the 47 samurai lined up in a row in front of Asano's tomb, announced the successful completion of their mission and all 47 of them committed seppuku (ritual suicide) as a punishment for their act of violence.

Historical Background Behind Tale of the 47 Rônin

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), samurai ideals were refined and codified even as the warriors no longer had cause to do battle. The ideal of selfless commitment, even the glorification of dying to express ones honor as a samurai, served as a mark of class as much as the swords that only samurai could wear. [Source:Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“In a rigidly structured class society, each class (samurai, peasants, merchants, artisans) had its own particular standards and values. For a member of a class that defined its worth by ideals of loyalty and service, to be masterless was to be in a kind of limbo. Rônin were samurai who had fallen from a high social position to a place outside the social scale entirely. Most often men became rônin because of defeat in battle, dereliction of duty, or because their masters suffered some disgrace. By contrast, in the American tradition of romanticizing outlaws, independence of spirit is idealized rather than specific loyalties, and to be unconnected to a respected position in society does not invariably imply disgrace.

Ronin Crossing the Bridge on the way to Moronao's Castle

“The motives and actions of the rônin, however, reflect ideals of Tokugawa society with which modern Japanese still have sympathy. Contemporary Japanese still value loyalty highly and identify closely with the groups to which they belong. For example, a businessman will introduce himself by saying his company's name before his own; the ties a student forms with his classmates in a school or university last throughout his career. A reading of the play will provide not only its own drama (and melodrama), but many examples of the ideal of loyalty and devotion to something outside oneself that account for the continuing popularity of the story.”

Plot Summary of 47 Ronin

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: The main plot of “Chûshingura: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers” “is based on the 1703 incident, but it is set in 1338 in order to avoid government censorship. Lord Asano becomes Lord Enya, and Kira is called Kô no Moronao. Various subplots are added, and we see the rônin in all aspects of life — in love and in conflict as well as in conspiracy. [Source:Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“In one subplot, the leader of the conspiracy, Yuranosuke, pretends to have sunk into chronic drunkenness. He flirts with Okaru, who was sold into prostitution so that her husband, Kampei, could join the conspiracy. Kampei proves his worthiness only as he dies, and becomes the forty-seventh member of the conspiracy posthumously. In another subplot,Yuranosuke's son Rikiya refuses to marry the woman he loves knowing he will soon die, although he cannot reveal his reason. Her father, who has acted prudently and without a true samurai disregard of death, restores his own honor by serving the conspirators and by finally dying well. These acts reunite his daughter with her love, if only for a night. There are more subplots as well as additions in later versions.

“Involved as the rônin were over the many months between the death of their lord and their act of revenge with finding means to live (since rônin lost their livelihoods when dismissed from service), with loves, greed and generosity, secrecy and fellowship, they were committed to this final act that they all knew would end in their own deaths. So while the emotions the people in the play Chûshingura feel — the love between parents and children, or husband and wife — are universal, they are expressed very differently, are directed toward different ends, and expressed in different actions. The story provides many examples of the classic tension the Japanese see existing between giri (duty) and ninjô (human feeling), a tension that should always be resolved in favor of giri. Note that the character who fails to make this commitment to duty is dropped from the group, and only regains his honor through a very complicated process after his death.”

Ronin breaking in to inner building at Moronao's Castle

Story of the 47 Rônin According to the Hagakure

The story of the 47 Rônin according to the “Hagakure” goes: “A certain person was brought to shame because he did not take revenge. The way of revenge lies in simply forcing ones way into a place and being cut down. There is no shame in this. By thinking that you must complete the job you will run out of time. By considering things like how many men the enemy has, time piles up; in the end you will give up. No matter if the enemy has thousands of men, there is fulfillment in simply standing them off and being determined to cut them all down, starting from one end. You will finish the greater part of it. [Source: “Hagakure: The Book of the Samurai,” by Yamamoto Tsunetomo, translated by William Scott Wilson (Kodansha International, 1992), 29-30; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Concerning the night assault of Lord Asano's rônin, the fact that they did not commit seppuku at the Sengakuji was an error, for there was a long delay between the time their lord was struck down and the time when they struck down the enemy. If Lord Kira had died of illness within that period, it would have been extremely regrettable. Because the men of the Kamigata area have a very clever sort of wisdom, they do well at praiseworthy acts but cannot do things indiscriminately, as was done in the Nagasaki fight. [The Nagasaki fight resulted from a man's accidentally splashing mud on a samurai of another clan. [Yamamoto] Tsunetomo feels that the men involved acted properly, because they took revenge immediately, without pausing to consider the cause or the consequences of what they were doing]

“Although all things are not to be judged in this manner, I mention it in the investigation of the Way of the Samurai. When the time comes, there is no moment for reasoning. And if you have not done your inquiring beforehand, there is most often shame. Reading books and listening to people's talk are for the purpose of prior resolution. Above all, the Way of the Samurai should be in being aware that you do not know what is going to happen next, and in querying every item day and night. Victory and defeat are matters of the temporary force of circumstances. The way of avoiding shame is different. It is simply in death. Even if it seems certain that you will lose, retaliate. Neither wisdom nor technique has a place in this. A real man does not think of victory or defeat. He plunges recklessly towards an irrational death. By doing this, you will awaken from your dreams.”

Graves of 47 Ronin at Sengaku-ji Temple in Tokyo

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016