UKIYO-E ARTISTS

Hiroshige Catching Fireflies

Sugimura Jihei is regarded as a master of black and white printing in which colors were applied by hand. The 18th century artist Okomura Masanabou is regarded as a major ukiyo-e innovator. A tireless self promoter, he used European one-point perspective beginning in 1745 and created works of great complexity.

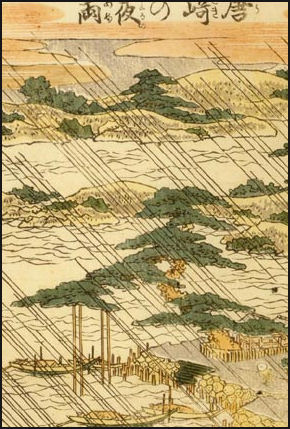

Suzuki Harunoby was the first to make full-color prints, His portfolio of woodcuts, “The Eight Parlor Views”, parodies of famous “Eight Views — “ paintings from China with scenes like “Returning Sails of the Towel Rack” and “Night Rain in the Heater Stand”. He also made irreverent nods to Chinese art such as “Emperor Genso and Yokihi”, which shows the last Tang emperor with his favorite concubine.

The Torii School, including the artists Torii Kiyomoto and Kiyonobu, played an important role in developing a branch of ukiyo called “yakushae” ("portraits of actors"). This art form helped popularize Kabuki and Kabuki in turn helped popularize it.

Great landscape artists include Katsushika Hokusai, Ando Hiroshige, Keisai Eisen and Torii Kiyongaga. The artists Suzuki Harunobu, Torii Kiyonaga and Kitagawa Utamaro were famous for making prints of extremely elegant and beautiful Japanese women.

Kumisada (later known as Toyokuni III) produced eh greatest number of works and headed one of the major schools of ukiyo-e artists in his time. Kuniyoshi, a contemporary of Kunisada, created works that ranged from dynamic warrior prints to landscape prints depicting the mood of Edo. Bu nether of tehse artists had sufficient opportunity for their works to be showsn, and they are still not well-known.

Sharaku and Utamoro

Toshusai Sharaku is famous for his portraits of kabuki actor made in 1794 and 1795, including humorous caricatures of scowling Kabuki actors with red bloodshot eyes. The cross-eye expression of the “mie” pose of some of figures was intended to indicate intense emotion. Little is known about Sharaku's life other than that he was a painting prodigy.

So little is known about Sharaku’s life some have theorized he may have actually been Hokusai or Utamaro or perhaps a Dutchman. Most scholars believe Sharaku was a noh actor known as Saito Jeroboa, who was employed by a lord living in Edo. He worked anonymously because it would have been scandalous for a noh actor associated with a samurai clan to be involved in low brow entertainment such as kabuki and ukiyo-e.

Sharaku was active for just 10 to 14 months in 1794 and 1795. SThere are said to be only 146 extant Sharaku works (or even fewer, depending on whom you ask).He was active for such a short time, many theorize, because he was concerned about being found out. Examinations of his paintings reveal unsteady lines and rough outlines, which were fixed by engravers and printers, in the ukiyo-e, supporting the claim he was not a professional artist.

“Sharaku became popular immediately after stepping onto the scene because he paid no attention to the boundaries set by existing painting methods," Hiroyoshi Tazawa, a curator of a Sharaku exhibit told the Yomiuri Shimbun. "Without belonging to any conventional school, Sharaku was free to express himself. So as soon as he made his debut, his uniqueness was widely welcomed."

Utamoro often produced works fro illustrated books with satirical poems and risque stories of famous people of the day. An association with book about the warlord Hideyoshi landed him in jail. Among Utamaro’s most memorable works “Amusements of Beauties in the Five Festivals “ (1901-04), “Customs of Beauties Around the Clock: Hour of the Cock (6 pm)”, “Servants from a Samurai Mansion” (1796-1804).

Sharaku’s Works

Kabuki actor by

Sharaku Sahaku’s work is divided into four stages Kumi Matsumaru wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Stage 1 focuses on his okubi-e, or large portraits. The bold and colorful expression of kabuki actors fully fill the spaces of each work. Looking at these extravagant ukiyo-e, finished with powdered mica, one can well imagine why kabuki-goers rushed to buy the prints when they were released.Tazawa said people in those days must have been overwhelmed by the depth of the okubi-e, achieved through the black background. “Because of its uniqueness and peculiarity, Sharaku's okubi-e style was taken up by other ukiyo-e artists, such as Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825) and Utagawa Kunimasa (1773-1810)," Tazawa said. [Source: Kumi Matsumaru, Daily Yomiuri, May 201, 2011]

In Stage 2, the works are all full-body images. Unlike the bold pieces of the previous satge those in this stage seem somehow subdued. Only three months after his okubi-e debut, Sharaku began releasing full-body ukiyo-e. Tazawa said these changes may have come at the suggestion of Tsutaya Juzaburo, a major ukiyo-e publisher, to expand the range of buyers by releasing more accessible works made from cheaper materials.

Some experts have said kabuki actors thought Sharaku's depictions of their expressions were too elaborate. "As can be seen in the works in Stage 3, Sharaku also painted trees and rooms in the background," Tazawa said. "You can feel the lines becoming even weaker in the works in Stage 4. The facial expressions also become monotonous and formalized...Usually, an artist's painting style doesn't change drastically in such a short period. This probably means Sharaku hadn't established his style before debuting. But he didn't necessarily improve during the 10 months he was on the scene," Tazawa said.

"Having seen all the works together, you realize Sharaku was not so good at depicting bodies, just like modern painters who only specialize in portraits," Tazawa said. "Even some of the pieces in Stage 1 show arms that look too short or in strange positions. You hardly know where the shoulders are in some of his ukiyo-e. This might have been done on purpose," Tazawa said. "But because of the differences in lines in the same ukiyo-e, some people have said there might've been 'another' Sharaku. There's no proof for this theory, though."

Sharaku’s Kabuki Pieces

actor by Utagawa The Actor Otani Oniji III as Edobei and The Actor Ichikawa Omezo I as the Manservant Ippei, both from the kabuki play Koinyobo somewake tazuna, are good examples of Sharaku's famed okubi-e portraits. The Actor Otani Oniji III as Edobei shows the character's eerie face as he prepares to attack his enemy Ippei. Facing the chief of the gang of thieves, Ippei, swinging his hair, wields a katana sword to defend himself.

The two prints of the men--both cross-eyed, a Sharaku specialty--depict a tense moment and fill up the prints, which are about 38 centimeters by 25 centimeters. "Sharaku made excellent use of distinctive shapes and line combinations in his expressive portraits, and he was effective at showing the characteristics of the different kabuki roles," Tazawa said." "He was also outstanding at making the viewer feel the personality of the actor, as in The Actor Ichikawa Ebizo as Takemura Sadanoshin. You can really feel the haggard side of the veteran actor with his wrinkled forehead and neck. The print can be enjoyed as a depiction of a certain character, but also as representing the actor himself. In that respect, Sharaku's ukiyo-e are more than just fun images of celebrities."

Tazawa said knowing the kabuki story the ukiyo-e is based on helps with understanding the piece, but "you can appreciate them even without any [kabuki] knowledge. Just like you can enjoy Cezanne without knowing about the artist."

Graphic Heroes and Magic Monsters by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Utagawa Kuniyoshi made heroic prints of samurai fighting whales and ghostly images of giant skeletons in prints with name like “Calming the Waves on the Way to Exile on Sado Island” and “One Hundred Heroic Generals in Battle at Kawanakajima “. Totoya Hokkei is known for producing dramatic, fantastic images such as “Yamamba and Two Tengu” (1818-30).

Ken Johnson wrote in the New York Times, “As elegantly sumptuous as they are imaginatively extravagant, Kuniyoshi’s greatest prints represent turbulent, epic visions of human protagonists battling supernatural beings on three-page spreads two and a half feet across, a format he invented. He also made portraits of attractive women in fashionable clothes, kabuki actors, comical montages of anthropomorphized cats and octopuses and antic, pornographic cartoons. [Source: Ken Johnson, New York Times, April 15, 2010]

Kuniyoshi produced some of his most important work in the 1840s during a period of censorship. Some art historians ahev argued that “the repressive strictures... productively challenged Kuniyoshi’s creative resourcefulness, forcing him to find ways to veil criticism of the shogunate allegorically.” “An 1843 triptych measuring more than 30 inches across and called “The Earth Spider Conjures Up Demons at the Mansion of Minamoto no Raiko “ depicts a visionary battle between two hordes of ghostly, comically misshapen devils looming in the immediate background as the ailing warrior Raiko lies in his sick bed, and his four bodyguards lounge in sumptuous robes in the foreground,” Johnson wrote. “This strange and beautiful print became a cause célèbre, as many interpreted it as a satire on the puritanical reforms of the day. The demons were thought to represent various sorts of decadence that the rules sought to limit, and the sick warrior was identified with the shogun who was chiefly responsible for the laws. Whether that was Kuniyoshi’s intended meaning there’s no telling, but when the print started to be acclaimed as a political critique, his frightened publisher withdrew it from circulation and planed down the blocks it was made from. The authorities evidently thought the image was a political critique; they jailed and fined an artist and a publisher who issued their own pirated version of Kuniyoshi’s print.”

“The curious thing about all this is that the image itself is so inexplicit. That the print might have meant something different than what was widely believed, however, was not so much at issue. Referring to controversy over another popular Kuniyoshi print not in the show, Mr. Clark writes, “As with the Earth Spider triptych, the authorities were alarmed not only by the question of who was “really” represented, but also by the generally unsettling effect of the “false rumors” (fuhyo) the image generated.” In other words, the authorities and the artists were at odds about an issue as old as Plato: From the ruler’s perspective, the problem with art is that it incites irrational passions. Artistic imagination per se — regardless of the politics it favors — stirs people up and causes trouble. Imagine how horrified the authorities would be by today’s almost completely unregulated visual culture in Japan and the rest of the modern capitalistic world.”

“The puritanical laws didn’t stop Kuniyoshi from producing some 10,000 prints by the time he died in his mid-60s in 1861, many of them technically virtuosic and flat-out gorgeous. The 1837 image of a naked, red-skinned boy wrestling a carp bigger than himself under a waterfall with a seemingly translucent curtain of liquid falling over the big fish, and a blizzard of little white bubbles dotting the whole is as exciting for its technical merit as for its mythic vision. A triptych from 1845-46, in which a giant, spectral skeleton conjured by an evil princess looms over a pair of battling, resplendently dressed warriors, and another from the same year showing the muscular hero Benkei dragging a giant bell up the slopes of Mount Hiei, are marvels of draftsmanship and fantastic visual storytelling....Considering the terrific imagination animating these and many other works... we may ask ourselves: What might Kuniyoshi have wrought had he been free to do whatever he wanted?”

Hokusai

Hokusai wave Katsuchika Hokusai (1760-1849) is Japan's most famous woodblock print artists. He produced woodblock prints, original drawings and printed books, In addition to his landscape paintings, including the renowned Fugaku Sanjurokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji), he produced pictures of beautiful women and illustrations for storybooks His distinctive painting style is said to have influenced master Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet and Vincent van Gogh.

A master of landscape prints, Hokusai made over 150 prints different prints of Mt. Fuji. His “Great Wave”, an image of a distant Mt. Fuji dwarfed a massive cresting wave, is perhaps the most famous work of Japanese art in the West and one of the most famous graphic images in the world. Equally famous is his “View of Mt. Fuji on a Fine, Breezy Day”. The Mt. Fuji paintings were parts of collections called “One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji and Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji”.

Hokusai was known for his sense of humor and is credited with coining the term "manga" to describe woodblock print cartoons. His works influenced Impressionist painters in France while Hokusia himself was inspired by Dutch landscapes. Towards the end of his life he signed his works “gakyorojin”, which means "old man mad with painting." Hokusai made his share of shunga erotic woodblock prints, sometimes signing them "Shishoku Ganko," a reference to a wild penis. A set a his works sold for $1.5 million at a Sotheby auction in 2003.

Hokusai worked as a professional artist for more than 70 years and lived to the age of 89, with his famous Fuji views coming at the end his career. Hokusai wanted desperately to live to a 100 , when he believed he would be worshiped like a god. Hokusai once wrote: “I began painting ukiyo-e when I was 50; but until I was 70, I didn’t produce anything of value...I will find my voice when I am 86, and will be well-versed in esoteric ukiyo-when I turn 90.

Book: “Hokusai” by Gian Carlo Calza (Phaidon, 2003, $95) is an outstanding coffee table book with beautifully reproduced prints, paintings and illustrations by the artist along with insightful and accessible essays about his work.

Hokusai’s Life

Hokusai began his career as an apprentice of the popular ukiyo-e artist Katsukawa Shunshu (1726-92). After his master died he produced a range of work that showed his skill as an artist dealing with a number of subjects and styles. He made hanging scrolls such as “Gathering Shellfish at Ebb-tide” (1808-13) and “Drunken Beauty” (1807) that showed both traditional Chinese and Japanese influences and Western techniques.

Hokusai’s 70-year career that began when he was 18 years old. Miki Kimura wrote in Yomiuri Shimbun: “Although Hokusai is known to have been born in Edo (present-day Tokyo), other details about how he spent his life are not well known. But there is a clue in one line Hokusai wrote in his later years in a postscript for an illustrated book--"From the time I was 6 years old, I had a habit of sketching the shapes of objects." [Source: Miki Kimura, Yomiuri Shimbun, November 9, 2012]

In his teens, Hokusai likely worked for a book-lending shop and studied how to carve a printing block under a sculptor. He made his debut as a portrait painter of kabuki actors, and later started painting beautiful women.

In his mid-40s, Hokusai was engaged in making illustrations for long novels called "yomihon," which became a major turning point for him. During the Bunka and Bunsei eras (1804-30), creators of yomihon endeavored to attract new readers in any way they could, which put illustrators' abilities to the test. To that end, Hokusai tried various measures. For example, in Yuriwaka Nozue no Taka (The Wild Falcon of Yuriwaka) (1808), an arrow is depicted near the beginning of the book as if it were driven through the book's seam. After reading along, I noticed the protagonist drawing a bow on a later page. This is a playful idea. His novel work became so popular that he illustrated nearly 200 books over about 10 years. As a result, the number of his fans and pupils increased.

From his 50s onward, Hokusai became absorbed in making collections of his illustrations. A good example is Hokusai Manga (Sketches by Hokusai) (1814-78), in which he captured the characteristics of insects, fish and plants. Published in 1814, the printed book sold better than expected and sequels were published one after another until 1878, long after his death. In Hokusai Manga, he drew anything and everything with freedom and humor, including the behavior of ordinary people, everyday items, animals, plants, and Shinto and Buddhist deities. The technique is superb. This free style of creation led to works of great innovation. Hokusai improved his ability to express an object's fine details while simultaneously employing the techniques of emphasis and omission to communicate in a very playful way. With these skills, he completed masterpieces of landscape painting such as Fugaku Sanjurokkei in his later years.

Hokusai left writing to the effect that he was able to gain some understanding of the framework of animals and what plants are even when he was 73 years old; he thought he might be able to improve on that knowledge at 86, understand the esoteric teachings at 90 and reach a world beyond human understanding at 100.

In his 80s, the last decade of his life, Hokusai devoted himself to religious painting based on records of ancient events and classic works, and to original drawings with natural motifs. He explored the world of painting beyond ukiyo-e. "Please keep me alive for 10 more years, no, for at least five years. Then, I'll become a genuine painter," he wrote. Even on the verge of death, he is said to have never lost his strong affection for painting.

Hokusai’s Art

Hokusa iNight Rain On the famous Mt. Fuji series, art historian Seiji Nakata of the Ota Memorial Museum of Art in Tokyo told the Daily Yomiuri: “Hokusai aimed at depicting the movements of light across Mt. Fuji. At this period Hokusai mainly aimed at drawing things that were difficult to draw’such as natural phenomena, seasons, lights. In the Mt. Fuji series he was interested in how the faces of the mountain changed depending on the season, weather and vantage point of the viewer.” Another one of Hokusai’s most famous works is “Alafuji “.

The “Great Wave”, actually entitled “Under the Wave off Kanagawa” was created around 1830-1833 as part of “36 Views of Mt. Fuji”. Hundreds of impressions were made of the original print but not many of them are in good condition. Describing an exquisite specimen at the British Museum, once critic wrote: “A subtle cloud formation — originally thought to have been pale pink — is sill visible in the sky...Mt. Fuji stands out strongly against a dark horizon that has been expertly inked and wiped by the printer, emphasizing a beautiful wood grain pattern found in very few other surviving examples.”

The Mt. Fuji pictures were made between 1830 and 1837 when Hokusai was in his 70s. “South Wind, Clear Dawn”, better known as “Pink Fuji” is another famous work from the same series. It featured a red Mt. Fuji in morning light. Art critic Mark Austin wrote un the Daily Yomiuri its “strikingly modern” style “whose flat, geometric planes, and opulent tones prefigure the early 20th century art deco works whose creators owe a debt to Hokusai.” In 2007, a “Pink Fuji” print was sold at a Christie’s auction for $602,100 — three times the asking price.

Describing “The Kirifuri Waterfall at Mt. Kuokamin in Shimotsuke Province” from Hokusai series “A journey to the Waterfalls of All the Provinces”, Austin wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “the cataract looks like a living thing’sinewy, dark-blue and white ribbons of water spill and chase over yellow and ocher rocks into a churning pool as five travelers look on, three by the pool at the foot of the picture and two near the top. The odd mixture of European one-point perspective...and Chinese multipoint perceptive give a hallucinatory effect.”

Meguri Nakayama of the Adachi Institute of Woodcut Prints told the Daily Yomiuri, “It requires a lot of talent to depict water as it is continuing flowing, so Hokusai’s use of water really shows Hokusai’s pride as an ukiyo-e artist. It’s as if he was taking a snapshot: he captures scenes with waves, flowing water and even wind. His technique far excels that of anybody else,”

Hiroshige

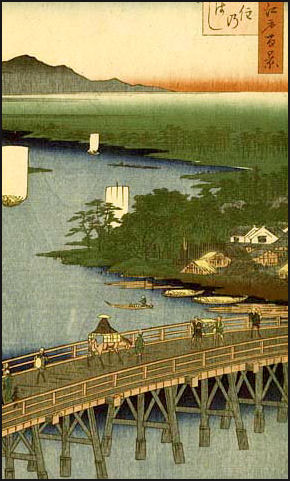

Hiroshige Bridge Utagawa (Ando) Hiroshige (1797-1858) is regarded as the last great ukiyo-e artist. His works were bestsellers in Japan and a favorite of the Impressionists. Van Gogh copied the Hiroshige's print “Shower on Ohashi Bridge at Atake”.

Western artist who were exposed to work by Hiroshige and other ukiyo-e artists were impressed not only by the colors but also by the novel perspectives, open vistas and lively expressions of wind and rain and other touches that gave atmosphere to the works of art.

Hiroshige was born a samurai and died a Buddhist monk and worked as an artist his entire life. He displayed talent at an early age and made his reputation with “Forty-Three Stations of Tokaido”. Tokaido was a highway between Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto. He probably died in a cholera epidemic in 1858.

Hiroshige’s work were snatched by tourists for less than a bowl of rice. He came into prominence in the 1930s with his series “The Fifty-Three Station of the Toikado”,” the great highway between the imperial city of Kyoto and the shogun’s seta of power in Edo. In the 1840s he completed “The Sixty-Nine Sation of the Kisokaido” , an important route through the central highlands of Japan.

Art By Hiroshige

Hiroshige liked the paint to scenes of places he traveled through. It is hard to retrace the route captured by “Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido Highway” because much of the route is covered by highways and railroad tracks. A similar series, “Sixty-nine Stations of the Nakasendo”, which traverses a mountainous route between Tokyo and Kyoto, can be enjoyed as much of the route is still on footpaths and quiet back roads.

Hiroshige produced more than 8,000 works, roughly 4,000 prints, 2,000 paintings and 2,000 drawings. Other famous works include 100 Famous Views of Edo (a set of 11 prints made from 1856 to 1858), which includes “Sudden Shower at Ohashi Bridge and “Eight Views of Omi” (Omi is now known as Lake Biwa) and delightful prints of plants and birds. “Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaido Nakasendoy” was done in collaboration with fellow ukiyo-e artist Keisai Eisen between 1830 and 1844.

Hiroshige began “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” the year he retired from the world to become a Buddhist monk and was not quite complete when Hiroshige died. Arranged by the season, it contains some of the artist most popular works. “Fox Fire at Enoki Tree on New Year’s Eve at Oji “ from the series, Austin wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “is a whimsical yet spooky depictions of foxes gathered under a holy Chinese nettle tree. A gray-blue wash conveys the chill, still winter night. The foxes’supernatural animals in Japanese folklore — are an eery shade of pink and red tongues of fire lick magically by their pointy heads.

Hiroshige also produced wonderful multi-figured scenes of everyday life and not so everyday life. One of these, “The Battle of Confectionery and Sake”, is a three-color woodblock print of massive food fight with sake bottles flying through the air and bean-paste-faced combatants fighting each other with dangos (rice flour dumplings) and baking tools.

Image Sources: British Museum, Library of Congress, National Museum in Tokyo

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013