HIDEYOSHI TOYOTOMI

Hideyoshi Toyotomi Hideyoshi Toyotomi is regarded as the George Washington and Napoleon of Japan. There are literally hundreds of books and comic books about him and one television mini-series about his life lasted an entire year. "No single person did more than Hideyoshi to shape the Japan of modern times," wrote Japan scholar and U.S. ambassador Edwin O. Reischauer.

A commoner by birth and without a surname, Hideyoshi was adopted by the Fujiwara family, given the surname Toyotomi, and granted the title kanpaku, representing civil and military control of all Japan. After more than a century of civil war and unrest, Hideyoshi restored order and unified all of Japan in 1590, after a famous battle at the Ara River in Yorii, involving 50,000 armed soldiers and the siege of hachigata castle. He helped establish Japan’s "brilliant and efficient social order that seemed to master anything to which it applied its collective will."

Hideyoshi Toyotomi was a small man with bug eyes. Known to some as Saru-san (Mr. Monkey), he is thought to have been the son of a farmer. Little is known about his early life. His ability to mobilize the masses is perhaps best demonstrated by the building of Osaka castle and its formidable walls by perhaps 100,000 men in three years.

According to Samurai Archives: Hideyoshi was "one of the most remarkable men in Japanese history." He "certainly cut an odd figure, especially as a general and later as a ruler. Short and thinly proportioned, Hideyoshi’s sunken features were likened to that of a monkey, with the rarely tactful Nobunaga taking to calling him Saru (monkey) and the 'bald rat'. He was said to enjoy his drink and women more then most and as a younger man made friends easily. He had an innate sense for manipulation and reading other men, attributes that no doubt helped him in his rise through the Oda ranks.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com; DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com; SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com; MUROMACHI PERIOD (1338-1573): CULTURE AND CIVIL WARS factsanddetails.com; MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com; ODA NOBUNAGA factsanddetails.com; TOKUGAWA IEYASU AND THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com; EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; LIFE IN THE EDO PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com; CULTURE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Essay on Epoch of Unification (1568-1615) aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Essay on Kamakura and Muromachi Periods aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Momoyama Period Wikipedia ; Hideyoshi Toyotomi bio zenstoriesofthesamurai.com ; Wikipedia article on Battle of Sekigahara Wikipedia ; Christianity in Japan: Japan-Photo Archive of Christianity japan-photo.de ; Wikipedia article on Christianity in Japan Wikipedia ; Catholic Encyclopedia Article on Japan (scroll down for info on Christianity in Japan) newadvent.org ; History of Japanese Catholic Church english.pauline.or.jp ; Artelino Article on the Dutch in Nagasaki artelino.com ; Samurai Era in Japan: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Sengoku Jidai. Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu: Three Unifiers of Japan” by Danny Chaplin Amazon.com; “Toyotomi Hideyoshi” by Stephen Turnbull and Giuseppe Rava Amazon.com; “The Swordless Samurai: Leadership Wisdom of Japan's Sixteenth-Century Legend---Toyotomi Hideyoshi” by Kitami Masao and Tim Clark Amazon.com; “Shogun: The Life and Times of Tokugawa Ieyasu: Japan's Greatest Ruler” (Tuttle Classics) by A. L. Sadler, Stephen Turnbull, Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga (Brill's Japanese Studies Library) by Gyūichi Ōta, Jurgis Elisonas, Jeroen P Lamers Amazon.com; “Japonius Tyrannus: The Japanese Warlord Oda Nobunaga Reconsidered (Japonica Neerlandica) by Jeroen Lamers Amazon.com; “Japan's Golden Age: Momoyama” by Money L. Hickman Amazon.com; “Shogun & Daimyo: Military Dictators of Samurai Japan” by Tadashi Ehara Amazon.com “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan” by Kozo Yamamura Amazon.com; “A History of the Samurai: Legendary Warriors of Japan” by Jonathan Lopez-Vera and Russell Calvert Amazon.com; “Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan” (1899) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com; “The Samurai Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Guide to Japan's Elite Warrior Class” by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com

Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s Life

Hideyoshi on his horse

According to Samurai Archives: Toyotomi Hideyoshi was born a peasant and yet rose to finally end the Sengoku Period. In fact, little is known for certain about Hideyoshi’s career prior to 1570, the year when he begins to appear in surviving documents and letters. The autobiography he commissioned begins with the year 1577 (the year he came into his own with an independent command to fight the Môri) and Hideyoshi himself was known to speak very little if at all about his past. [Source: Samurai Archives |~|]

According to tradition, Hideyoshi was born in a village called Nakamura in Owari province, the son of a foot-soldier/peasant known to us as Yaemon. Hideyoshi’s childhood name is recorded as Hiyoshimaru, or 'bounty of the sun', quite possibly a later embellishment contrived to give substance to a claim of divine inspiration Hideyoshi made regarding his birth. The popular image of Hideyoshi’s youth has him being shipped off to a temple, only to depart in search of adventure. He travels all the way to the lands of Imagawa Yoshimoto and serves there for a time, only to abscond with a sum of money entrusted into his care by Matsushita Yukitsuna. Hiyoshi (now known as Tokachiro) returns to Owari (around 1557) and finds service with the young Oda Nobunaga, whose attention he manages to secure. He somehow becomes involved with the rebuilding of Kiyosu Castle and acts as a foreman, all the while earning the enmity of the senior Oda retainers. |~|

Tokachiro is then given a position as one of Nobunaga’s sandal-bearers and is present for the Battle of Okehazama in 1560; by 1564 he becomes known as Kinoshita Hideyoshi and manages to bribe a number of Mino warlords to desert the Saito. By now, Nobunaga has become impressed with Hideyoshi’s natural talent, and it’s thanks to Hideyoshi that Inabayama is taken with ease in 1567 (owing to Hideyoshi throwing up a fort at nearby Sunomata and discovering a secret route leading to the rear of Inabayama). Some time later, probably in 1573, Hideyoshi adopted the surname Hashiba, which he created by borrowing characters from two ranking Oda retainers, Niwa Nagahide and Shibata Katsuie. By this time he is married to a woman known as Nene (or O-ne); his mother had by now remarried, and through her marriage to a certain Chikuami produced Hidenaga, Hideyoshi’s trusted half-brother. |~|

Hideyoshi commanded troops at the Battle of Anegawa in 1570 and was active in Nobunaga’s campaigns against the Asai and Asakura; he finally and definitively emerges into the light of history in 1573. In that year Nobunaga destroyed the Asai clan of Omi and assigned Hideyoshi three districts in the northern part of that province. Initially based at Odani, the former Asai headquarters, Hideyoshi soon moved to Imahama, a port on Lake Biwa. Once there he set to work on domestic affairs, which included increasing the output at the local Kunimoto firearms factory (established some years previously by the Asai and Asakura). With Nobunaga engaged in almost constant warfare, Hideyoshi earned plenty of battlefield experience over the next few years, flying his 'golden gourd' standard at Nagashima (1573, 1574), Nagashino (1575), and Tedorigawa (1577). |~|

Hideyoshi Takes Control of Japan After Oda Nobunaga’s Death

Oda Nobunaga

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: In 1582, a fire all around his quarters awakened Oda in the middle of the night. A subordinate general had betrayed him. Seeing no way out of the flames, he committed suicide. Another of his generals, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598), who, at the time of Oda’s death, was busy fighting in the north of Japan, rushed back to Kyoto upon hearing the news. He quickly killed Oda’s betrayer and, able to take the "moral" high ground as avenger of his lord’s death, took over command of Oda’s organization. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Hideyoshi finished the work Oda had started. After destroying the forces responsible for Nobunaga’s death, Hideyoshi was rewarded with a joint guardianship of Nobunaga’s heir, who was a minor. By 1584 Hideyoshi had eliminated the three other guardians, taken complete control of Kyoto, and become the undisputed successor of his late overlord. [Source: Library of Congress]

By 1985 Hideyoshi he had secured alliances with three of the nine major daimyo coalitions. He continued the war of reunification in Shikoku and northern Kyushu but for all intents and purposes had subdued the main part of Japan. The only possible exception was a daimyo named Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616), another of Oda’s generals. Hideyoshi worked out a truce with Ieyasu under which Ieyasu supported Hideyoshi but also received a small empire consisting of eight provinces. While Hideyoshi was alive, there was no open conflict between he and Ieyasu, but Ieyasu remained a separate power outside of Hideyoshi’s complete control.” ~

In 1590, with an army of 200,000 troops, Hideyoshi defeated his last formidable rival, who controlled the Kanto region of eastern Honshu. The remaining contending daimyo capitulated, and the military reunification of Japan was complete. Hideyoshi reunified Japan after over a century of civil war and political instability.[Source: Library of Congress *]

Japan Under Hideyoshi

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

All of Japan was controlled by the dictatorial Hideyoshi either directly or through his sworn vassals, and a new national government structure had evolved: a country unified under one daimyo alliance but still decentralized. The basis of the power structure was again the distribution of territory. A new unit of land measurement and assessment--the koku--was instituted. One koku was equivalent to about 180 liters of rice; daimyo were by definition those who held lands capable of producing 10,000 koku or more of rice. Hideyoshi personally controlled 2 million of the 18.5 million koku total national assessment (taken in 1598). Tokugawa Ieyasu, a powerful central Honshu daimyo (not completely under Hideyoshi’s control), held 2.5 million koku. [Source: Library of Congress *]

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: A “key element in efficient taxation is knowing how much everyone has. To this end, Hideyoshi ordered a massive cadastral survey. Teams of officials went out with poles and other measuring devices in hand and measured every foot of farmland. They also assessed the quality of each plot of land and its expected productivity. The survey teams compiled all this information, which took years to gather completely, into detailed registers. These records remained the basis of taxation in many parts of Japan until the middle of the nineteenth century. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The unification of Japan and the creation of a lasting national polity in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries required more than just military exploits. Japan’s “three unifiers,” especially Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536- 1598) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), enacted a series of social, economic, and political reforms in order to pacify a population long accustomed to war and instability and create the institutions necessary for lasting central rule. Although Hideyoshi and Ieyasu placed first priority on domestic affairs — especially on establishing authority over domain lords, warriors, and agricultural villages — they also dictated sweeping changes in Japan’s international relations. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Hideyoshi Influential Social Policies

Despite Hideyoshi’s tremendous strength and the fear in which he was held, his position was far from secure. He attempted to rearrange the daimyo holdings to his advantage by, for example, reassigning the Tokugawa family to the conquered Kanto region and surrounding their new territory with more trusted vassals. He also adopted a hostage system for daimyo wives and heirs at his castle town at Osaka and used marriage alliances to enforce feudal bonds. He imposed the koku system and land surveys to reassess the entire nation. [Source: Library of Congress *]

As ruler Hideyoshi enacted several important policies that helped shape the structure of society and government for centuries after his death. In 1590, he declared an end to any further class mobility or change in social status, reinforcing the class distinctions between cultivators and bushi (only the latter could bear arms). He provided for an orderly succession in 1591 by taking the title taiko, or retired kanpaku, turning the regency over to his son Hideyori. Only toward the end of his life did Hideyoshi try to formalize the balance of power by establishing certain administrative bodies: the five-member Board of Regents (one of them Ieyasu), sworn to keep peace and support the Toyotomi, the five-member Board of House Administrators for routine policy and administrative matters, and the three-member Board of Mediators, who were charged with keeping peace between the first two boards. *

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: Hideyoshi was himself of peasant origin, but he took steps to make sure that no peasant would again rise to fame and power as a general. He decreed a formal, rigid division between warriors (commonly known by the Japanese term samurai) and everyone else ("commoners"). This decree was the origin of the samurai class as a clearly defined, legal entity. Those who were part-time warriors and part-time farmers or merchants had to choose between military or civilian life. After separating the warriors from the rest of society, Hideyoshi then collected all offensive weapons (e.g., long swords, certain types of firearms) from the commoners in what is called the "Sword Hunt" Ostensibly, he had the weapons collected to be melted down and made into a huge Buddha image. Religious piety, however, was not the real reason. As you can imagine, it is much easier to collect taxes from a disarmed populace. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Hideyoshi, Culture and Art

The arts flourished under Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The new elite commissioned artists to produce grand works of art to decorate their palaces. The Kano School, famous for its gilded partition paintings of rich landscapes, flowers, birds and trees, emerged in the Momoyama Period (1573-1603) and remained popular through the Edo Period.

Momoyama art is named after the hill on which Hideyoshi built his castle at Fushima, south of Kyoto. It was a period of interest in the outside world, the development of large urban centers, and the rise of the merchant and leisure classes. Ornate castle architecture and interiors adorned with painted screens embellished with gold leaf reflected daimyo power and wealth. Depictions of the "southern barbarians"--Europeans--were exotic and popular. *

Momoyama Period Kano school painting

Japanese ceramics flourished during the Momoyama Period and it development as an art form was boosted by the popularity of the tea ceremony. Famous Oribe and Shinto tea ceremony ceramics were produced under the direction of tea master Furuta Oribe and Sen no Rikyo. The master potter Chojiro developed the raku-yaki style of pottery after being ordered to do so by the shogun.

Hideyoshi Toyotomi built a golden tea ceremony room. A replica of the room was built in 2008 and displayed in a Japanese department store. The room is 2.5 meters high with a floor that covered 3½ tatami mats. It took eight months to restore with 15,000 pieces of gold leaf worth about $1 million. Inside is a $3.5 million tea set made entirely of gold.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The decorative style that is the hallmark of Momoyama art had its inception in the early sixteenth century and lasted well into the seventeenth. On the one hand, the art of this period was characterized by a robust, opulent, and dynamic style, with gold lavishly applied to architecture, furnishings, paintings, and garments. The ostentatiously decorated fortresses built by the daimyo for protection and to flaunt their newly acquired power exemplified this grandeur. On the other hand, the military elite also supported a counter-aesthetic of rustic simplicity, most fully expressed in the form of the tea ceremony that favored weathered, unpretentious, and imperfect settings and utensils. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Asian Art. "Kamakura and Nanbokucho Periods (1185–1392)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2002, metmuseum.org \^/]

Hideyoshi, Foreign Trade and Christianity

In 1577 Hideyoshi had seized Nagasaki, Japan’s major point of contact with the outside world. He took control of the various trade associations and tried to regulate all overseas activities. Although China rebuffed his efforts to secure trade concessions, Hideyoshi succeeded in sending commercial missions to present-day Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. He was suspicious of Christianity, however, as potentially subversive to daimyo loyalties and he had some missionaries crucified. *

Dutch and Chinese settlement in Nagasaki

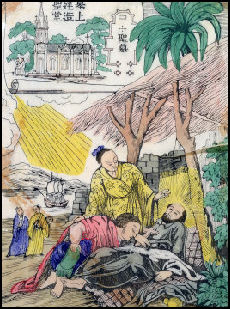

Hideyoshi initially welcomed the foreigners. He gave personal tours of his castles to a group of Jesuits. He began a campaign against Christianity in 1597 when he learned that Conquistadors followed missionaries in Latin America and that missionaries were active in the nearby Philippines. He banned Christianity, passed anti-Christian legislation and ordered the "Pope’s generals" (missionaries) out. In 1597, 26 Catholics, including six foreigners and a 12-year-old Japanese boy were crucified on hill in Nagasaki. All 26 were later canonized as saints by the Catholic church.

The heaviest repression took place in the early 1600s, when around 6,000 Christians were killed, mostly in the southern part of Japan, when Portuguese missionaries from Macao made the greatest inroads. Most of the dead were merchants and peasants. samurai and noblemen were forced to renounce the religion under pressure.

Christians were branded with hot irons, boiled alive in hot springs and tortured in other ways. Christians were rooted out by asking people to step on copper or wooden tablets with copper or wooden tablet with images of the Virgin Mary and Baby Jesus. Those who refused to step on them were recognized as Christians and were persecuted. Persecution of Christians continued under the Tokugawa, reaching its peak in 1637.

In May 2007, 188 16th-century Japan martyrs were beautified by Pope Benedict XVI. The 188 included on entire family The majority were laymen. A third were women. Before that 247 people related to Japan had either been beautified or canonized, including the 26 martyrs, four Spaniards, one Mexican and one Portugese, killed in Nagasaki in 1597

See Separate Article CHRISTIANITY AND HIDDEN CHRISTIANS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Edict of Toyotomi Hideyoshi: “Limitation on the Propagation of Christianity, 1587"

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The years from 1549 to 1639 are sometimes called the “Christian century” in Japan. In the latter half of the sixteenth century, Christian missionaries, especially from Spain and Portugal, were active in Japan and claimed many converts, including among the samurai elite and domain lords. The following edicts restricting the spread of Christianity and expelling European missionaries from Japan were issued by Hideyoshi in 1587. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Christian fumie (image to step on)

Excerpts from the “Limitation on the Propagation of Christianity” edict issued on the Fifteenth year of Tenshō [1587], sixth month, 18th day by Toyotomi Hideyoshi” : 1) Whether one desires to become a follower of the padre is up to that person’s own conscience. 2) If one receives a province, a district, or a village as his fief, and forces farmers in his domain who are properly registered under certain temples to become followers of the padre against their wishes, then he has committed a most unreasonable illegal act. [Source: “Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period”, edited by David J. Lu (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 196-197]

3) When a vassal (“kyūnin”) receives a grant of a province or a district, he must consider it as property entrusted to him on a temporary basis. A vassal may be moved from one place to another, but farmers remain in the same place. Thus if an unreasonable illegal act is committed [as described above], the vassal will be called upon to account for his culpable offense. The intent of this provision must be observed.

4) Anyone whose fief is over 200 “chō “and who can expect two to three thousand “kan “of rice harvest each year must receive permission from the authorities before becoming a follower of the padre. 5) Anyone whose fief is smaller than the one described above may, as his conscience dictates, select for himself from between eight or nine religions.

- If a “daimyō “who has a fief over a province, a district, or a village, forces his retainers to become followers of the padre, he is committing a crime worse than the followers of Honganji who assembled in their temple [to engage in the Ikkō riot]. This will have an adverse effect on [the welfare of] the nation. Anyon who cannot use good judgment in this matter will be punished.

Edict of Toyotomi Hideyoshi: “Expulsion of Missionaries, 1587"

St. Francis Xavier Excerpts from the “Expulsion of Missionaries, 1587" edict issued on the Fifteenth year of Tenshō [1587], sixth month, 19th day by Toyotomi Hideyoshi : 1) Japan is the country of gods, but has been receiving false teachings from Christian countries. This cannot be tolerated any further. [Source: “Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period”, edited by David J. Lu (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 196-197]

2) The [missionaries] approach people in provinces and districts to make them their followers, and let them destroy shrines and temples. This is an unheard of outrage. When a vassal receives a province, a district, a village, or another form of a fief, he must consider it as a property entrusted to him on a temporary basis. He must follow the laws of this country, and abide by their intent. However, some vassals illegally [commend part of their fiefs to the church]. This is a culpable offense.

3) The padres, by their special knowledge [in the sciences and medicine], feel that they can at will entice people to become their believers. In doing so they commit the illegal act of destroying the teachings of Buddha prevailing in Japan. These padres cannot be permitted to remain in Japan. They must prepare to leave the country within twenty days of the issuance of this notice.

4) The black [Portuguese and Spanish] ships come to Japan to engage in trade. Thus the matter is a separate one. They can continue to engage in trade. 5) Hereafter, anyone who does not hinder the teachings of the Buddha, whether he be a merchant or not, may come and go freely from Christian countries to Japan.

Edict of Toyotomi Hideyoshi: Collection of Swords, 1588

Samurai with weapon

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ In 1588, in what has come to be known as the “sword hunt,” Hideyoshi decreed that farmers should be disarmed, essentially guaranteeing the samurai elite a monopoly on the instruments of violence. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Excerpts from “Collection of Swords” edict issued on the Sixteenth year of Tenshō [1588], seventh month, 8th day, 1588 by Toyotomi Hideyoshi: 1) Farmers of all provinces are strictly forbidden to have in their possession any swords, short swords, bows, spears, firearms, or other types of weapons. If unnecessary implements of war are kept, the collection of annual rent (“nengu”) may become more difficult, and without provocation uprisings can be fomented. Therefore, those who perpetrate improper acts against samurai who receive a grant of land (“kyūnin”) must be brought to trial and punished. However,in that event, their wet and dry fields will remain unattended, and the samurai will lose their rights (“chigyō”) to the yields from the fields. Therefore, the heads of the provinces, samurai who receive a grant of land, and deputies must collect all the weapons described above and submit them to Hideyoshi’s government. [Source: “Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period”, edited by David J. Lu (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 191-192]

2) The swords and short swords collected in the above manner will not be wasted. They will be used as nails and bolts in the construction of the Great Image of Buddha. In this way, farmers will benefit not only in this life but also in the lives to come.

- If farmers possess only agricultural implements and devote themselves exclusively to cultivating the fields, they and their descendants will prosper. This compassionate concern for the well.being of the farms is the reason for the issuance of this edict, and such a concern is the foundation for the peace and security of the country and the joy and happiness of all the people.

All the implements cited above shall be collected and submitted forthwith...Commentary All the swords possessed by farmers in this country have been collected for the ostensible purpose of making nails for the erecting of the Great Image of Buddha. … But truthfully, this is a measure specifically adopted to prevent occurrence of peasant uprisings (“ikki”). Indeed various motivations are behind this.

Hideyoshi Invades Korea

Hideyoshi’s major ambition was to conquer China but to reach it he had to pass through Korea first. Hideyoshi Toyotomi launched two unsuccessful invasions of Korea---in 1592 and 1597. Before they were driven out, Hideyoshi’s armies killed 100,000 Koreans. A mound near Kyoto known as Mimizuka contains the chopped-off noses of hundreds (maybe thousands) of Koreans killed in the campaign. The second invasion of Korea was quickly aborted after Hideyoshi’s death in 1598. In 1597 a second invasion was begun, but it abruptly ended with Hideyoshi’s death in 1598. *

In 1592, with an army of 200,000 troops, Hideyoshi invaded Korea, then a Chinese vassal state, for the first time. His armies quickly overran the peninsula before losing momentum in the face of a combined Korean-Chinese force. During peace talks, Hideyoshi demanded a division of Korea, freetrade status, and a Chinese princess as consort for the emperor. The equality with China sought by Japan was rebuffed by the Chinese, and peace efforts ended.

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “Historians sometimes debate Hideyoshi’s motivation for the invasion. Some, for example, say the primary reason was to find an outlet for the energies of the many warriors in Japan, whose restlessness might have caused trouble at home. Others point out that Hideyoshi had even made plans for the conquest of India. Therefore, his own personal megalomania was the primary motivating force. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Whatever Hideyoshi’s reasons may have been, a Japanese force of over 150,000 attacked Korea in 1592. Some members of the Korean court had warned the king and officials about the possibility of a Japanese invasion. But these warnings went unheeded, and the Korean side was unprepared. The seasoned warriors in Japan’s army won victory after victory and soon overran the Korean capital. The Japanese forces continued northward toward China, but before they could enter China, a hastily-assembled Ming army engaged them in battle. From Ming China’s point of view, it was better to fight Japan in Korea than in China. This Ming army stopped the Japanese advance but did not decisively defeat the Japanese army.~

“After the initial Japanese victories, the war settled into a stalemate. Japanese forces held the major Korean cities. The were unable, however, to advance into China and came under constant harassment in outlying areas from bands of Korean and Chinese soldiers. The war at sea went much worse for Japan. Korea was fortunate to have a brilliant admiral, Yi Sun-sin, whose forces kept constant pressure on Japanese supply lines. Admiral Yi created a radically new type of fighting ship: the world’s first ironclad vessel. Called"turtle ships" because of their appearance, these low-profile, iron-plated ships were almost immune from enemy gunfire. They wreaked havoc on the Japanese navy. ~

Japanese ships attacking Korea

“Hideyoshi eventually entered into negotiations with Ming China. The negotiations were a classic case of poor communication. The Ming emperor, misled by his officials who were reluctant to admit the extent of Japanese victories, was convinced that Hideyoshi was ready to surrender and become a vassal of Ming China. Hideyoshi, on the other hand, expected the Chinese side to be forthcoming with major concessions. When Hideyoshi finally discovered the truth, he exploded with rage and ordered a second invasion in 1597. The second invasion force numbered about 140,000. They scored a number of important victories, but Hideyoshi died in 1598 before the final outcome could be settled decisively. At this point, the major daimyo met in a council. None were enthusiastic about continuing the war, and they ordered the withdrawal the entire Japanese force. The war ended after years of bloodshed and devastation with nothing positive accomplished by any of the parties involved. The only possible exception was that Korean prisoners of war introduced a number of new cultural forms to Japan, particularly in the area of pottery.” ~

Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Death

On his deathbed in 1598, Toyotomi Hideyoshi was determined that his family stay in power. He made each of the most powerful leaders of the country swear allegiance to his 5-year-old son, Hideyori. According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: “There is good evidence that Hideyoshi had become mentally unstable toward the end of his life. He certainly became more murderous (and he had a macabre interest in ears). Unable to produce a male child of his own, he eventually adopted a son and heir. Late in his life, one of Hideyoshi’s wives unexpectedly gave birth to a healthy boy. Now with a biological son of his own, Hideyoshi ordered his adopted son to kill himself. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“At the time of Hideyoshi’s death, however, his son was still a small child. Hideyoshi was rightly worried that this child would not fare well in the brutal political world of late sixteenth-century Japan. Hideyoshi appointed a council of leading daimyo to rule as a regency until his son came of age. As he lay dying, Hideyoshi required these daimyo to swear eternal loyal to Hideyoshi’s son. Honesty and trustworthiness, however, were not qualities the leading daimyo of that time possessed.” ~

After Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Death

As soon as Hideyoshi died, the leading daimyo began eyeing each other with suspicion and jockeying for strategic advantage. At that time, the most powerful of the five leaders was Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was based as Fushimi Castle and the leader of the Eastern Army. The second most powerful was Ishida Mitsunari, based at Osaka Castle and leader of the Western Army and loyal to Hideyoshi’s heir.

A decisive battle took place in 1600. Suspicious of Ieyasu’s lust for power Mitsunari fomented a rebellion in Ieyasu’s territory, forcing Ieyasu to leave Fushimi with the greater part of his army. Fushimi Castle was left under the command of Torii Mototada and a force of 1,800 samurai. On July 16, Mitsunari besieged the castle with a 40,000-man army. Mototada’s force held on for two weeks but was reduced to only 380 men.

Mass Suicide of 380 Samurai and the Battle of Sekigahara

On August 1, 1600, a fire was set inside the castle, perhaps by a ninja. Some of Mitsunari’s soldiers managed to enter the castle and surround the 380 samurai. Rather than give up Mototada order his enemies to chop of his head, which they in full view of the 380 samurai, who then followed their leader’s example and committed seppuku (ritual suicide). The fall of Fushimi encouraged other leaders to join Mitsunari. Their combined force met Ieyasu’s army on September 15 at Sekigahara, 60 miles northwest of Kyoto.

The Battle of Sekigahara on October 21, 1600 is one of the most important battles in Japanese history. The Eastern Army of Ieyasu faced off against the Western Army of Mitsunari. Each army contained more than 80,000 men. The Eastern Army of Ieyasu routed the Western Army of Mitsunari, paving the way for Ieyasu to claim the Shogunate. Ieyasu won the day by employing some underhanded trickery. He convinced a Western Army general to switch sides at the last minute. Samurai under the general’s command attacked the Western Army from the rear, causing it to fragment and open itself to attacks from the Eastern Army. Today a plinth marks the spot where Ieyasu’s generals presented him with thousands of heads. Three years later Ieyasu was given the title of shogun.

After Tokugawa Ieyasu’s decisive victory he was the most powerful person in Japan. Ieyasu was more than an excellent general. He was also a shrewd politician and institution builder. In the course of capitalizing on his victory, Ieyasu established a strong and stable bakufu that ruled Japan until the 1860s. The period from 1603, the date Ieyasu formally took the title of shogun, until the last shogun’s resignation in 1867, is known as the Tokugawa period or Edo period.

Image Sources: JNTO, Tokyo National Museum, Samurai Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016