TOKUGAWA IEYASU

Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616) became shogun in 1603 after the victory at Sekigahara in 1600. He ate fur seal extracts for strength and ruled for 13 years before he died in 1616. His leadership was a major turning point in Japanese history. The shoguns of the Tokugawa family, known as the Tokugawa shogunate, maintained control of Japan for the next 265 years and created political and social institutions that defined almost every facet of the nation’s life.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Tokugawa Ieyasu was the third of the three great unifiers of Japan and the founder of the Tokugawa shogunate that ruled Japan from 1603 to 1868. The establishment of a stable national regime was a substantial achievement, as Japan had lacked effective and durable central governance for well over a century prior to Ieyasu’s rise. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Ieyasu’s victory over the western daimyo at the Battle of Sekigahara (1600) gave him virtual control of all Japan. He rapidly abolished numerous enemy daimyo houses, reduced others, such as that of the Toyotomi, and redistributed the spoils of war to his family and allies. Ieyasu still failed to achieve complete control of the western daimyo, but his assumption of the title of shogun helped consolidate the alliance system. After further strengthening his power base, Ieyasu was confident enough to install his son Hidetada (1579-1632) as shogun and himself as retired shogun in 1605. The Toyotomi were still a significant threat, and Ieyasu devoted the next decade to their eradication. In 1615 the Toyotomi stronghold at Osaka was destroyed by the Tokugawa army.

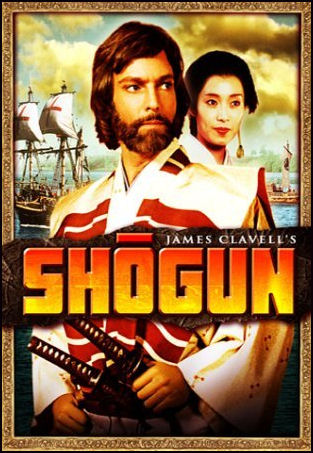

Tokugawa Ieyasu was the shogun in James Clavell’s “Shogun.” The “Shogun” story is based on the adventures of William Adams, an English ship pilot who lived in Japan from 1600 to 1620 and befriended Ieyasu. Adams arrived in Japan on a Dutch ship. He was imprisoned after his arrival on the bequest of a Portuguese priest and was released and invited to visit the shogun’s court in Osaka. As an advisor to Ieyasu, Adams gave the Japanese advise on making Western-style ships and served as a diplomat in sort of the same way that Marco Polo did for Kublai Khan. For his efforts Adams was rewarded with the title of samurai and given an estate on Miura peninsula and was granted permission to open a trading post for the English. Adam’s status and influence was luck ran out when out Ieyasu died. Adam’s story is told in the book “Samurai William: The Englishman Who Opened Japan” by Giles Milton.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: SAMURAI, MEDIEVAL JAPAN AND THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com;

DAIMYO, SHOGUNS AND THE BAKUFU (SHOGUNATE) factsanddetails.com;

SAMURAI: THEIR HISTORY, AESTHETICS AND LIFESTYLE factsanddetails.com;

SAMURAI CODE OF CONDUCT factsanddetails.com;

SAMURAI WARFARE, ARMOR, WEAPONS, SEPPUKU AND TRAINING factsanddetails.com;

FAMOUS SAMURAI AND THE TALE OF 47 RONIN factsanddetails.com;

MOMOYAMA PERIOD (1573-1603) factsanddetails.com;

ODA NOBUNAGA factsanddetails.com;

HIDEYOSHI TOYOTOMI factsanddetails.com;

EDO (TOKUGAWA) PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com;

LIFE IN THE EDO PERIOD (1603-1867) factsanddetails.com;

CULTURE IN JAPAN IN THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com;

JAPAN AND THE WEST DURING THE EDO PERIOD factsanddetails.com;

DECLINE OF THE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on the Edo Period: Essay on Epoch of Unification (1568-1615) aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Essay on the Polity opf the Tokugawa Era aboutjapan.japansociety.org ; Wikipedia article on the Edo Period Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on the History of Tokyo Wikipedia; Making of Modern Japan, Google e-book books.google.com/books ; Wikipedia article on the Momoyama Period Wikipedia ; Christianity in Japan: Japan-Photo Archive of Christianity japan-photo.de ; Wikipedia article on Christianity in Japan Wikipedia ; Catholic Encyclopedia Article on Japan (scroll down for info on Christianity in Japan) newadvent.org ; History of Japanese Catholic Church english.pauline.or.jp ; Artelino Article on the Dutch in Nagasaki artelino.com ; Samurai Era in Japan: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; Artelino Article on Samurai artelino.com ; Wikipedia article om Samurai Wikipedia Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co ; Good Japanese History Websites: ; Wikipedia article on History of Japan Wikipedia ; Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com ; National Museum of Japanese History rekihaku.ac.jp ; English Translations of Important Historical Documents hi.u-tokyo.ac.jp/iriki ; Kusado Sengen, Excavated Medieval Town mars.dti.ne.jp ; List of Emperors of Japan friesian.com Books : “Edo, The City That Became Tokyo: An Illustrated History” by Akira Naito (Kodansha Press, 2003) and “Giving Up the Gun, Japan’s Reversion from the Sword “ by Noel Perrin.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Shogun: The Life and Times of Tokugawa Ieyasu: Japan's Greatest Ruler” (Tuttle Classics) by A. L. Sadler, Stephen Turnbull, Alexander Bennett Amazon.com; “Sengoku Jidai. Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu: Three Unifiers of Japan” by Danny Chaplin Amazon.com; “Shogun” by James Clavell Amazon.com: “Toyotomi Hideyoshi” by Stephen Turnbull and Giuseppe Rava Amazon.com; “The Swordless Samurai: Leadership Wisdom of Japan's Sixteenth-Century Legend---Toyotomi Hideyoshi” by Kitami Masao and Tim Clark Amazon.com; “The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga (Brill's Japanese Studies Library) by Gyūichi Ōta, Jurgis Elisonas, Jeroen P Lamers Amazon.com; “Japonius Tyrannus: The Japanese Warlord Oda Nobunaga Reconsidered (Japonica Neerlandica) by Jeroen Lamers Amazon.com; “Japan's Golden Age: Momoyama” by Money L. Hickman Amazon.com; “Shogun & Daimyo: Military Dictators of Samurai Japan” by Tadashi Ehara Amazon.com “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 3: Medieval Japan” by Kozo Yamamura Amazon.com; “A History of the Samurai: Legendary Warriors of Japan” by Jonathan Lopez-Vera and Russell Calvert Amazon.com; “Bushido: The Samurai Code of Japan” (1899) by Inazo Nitobe Amazon.com; “The Samurai Encyclopedia: A Comprehensive Guide to Japan's Elite Warrior Class” by Constantine Nomikos Vaporis and Alexander Bennett Amazon.com

Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s Life

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Life

According to to Samurai Archives: Tokugawa Ieyasu was born Matsudaira Takechiyo, the son of Matsudaira Hirotada (1526-1549), a relatively minor Mikawa lord who had spent much of his young life fending off the military advances of the Oda. and the political ploys of the Imagawa. In 1548 the Oda attacked Mikawa, and Hirotada turned to Imagawa Yoshimoto for assistance. Yoshimoto was only too willing to throw the considerable weight of the Imagawa in with Hirotada but on the condition that Hirotada’s young son be sent to Sumpu as a hostage. [Source: Samurai Archives |~|]

Tokugawa Ieyasu at the entrance to a palace

Unfortunately, the wily Oda Nobuhide caught wind of the deal, and saw to it that Takechiyo’s entourage was intercepted on the road to Suruga. Takechiyo was wisked away to Owari and confined to Kowatari Castle. While he was not badly treated, Nobuhide threatened to put him to death unless Hirotada renounce his ties with the Imagawa and ally with the Oda. Hirotada wisely elected to call his Owari rival’s bluff and made no response except to say that the sacrifice of his own son could only impress upon the Imagawa his dedication to their pact. Later a deal was struck with Oda Nobunaga that some of his captured relatives would be spared in return for the release of Takechiyo. |~|

Takechiyo came of age 1556, and received the name Matsudaira Motoyasu, the MOTO coming from Yoshimoto himself. He was allowed to return to Mikawa that same year, and was tasked with fighting a series of battles against the Oda on the Imagawa’s behalf. For all the damage the years of Imagawa interference and in-fighting had wrought, the famed fighting spirit of the Mikawa samurai was hardly tarnished. Motoyasu scored a notable local victory at Terabe and made a name for himself (at Nobunaga’s expense) with the provisioning of Odaka. In that instance, Motoyasu had brought in much-needed supplies to a beleaguered fort by tricking the bulk of the attackers into marching away to face a non-existent enemy army. |~|

Pragmatic despite his youth, Motoyasu proceeded to strike up an alliance with Nobunaga, though initially in secret - a number of his close family (including his infant son) were still held hostage in Sumpu by Yoshimoto’s successor, Ujizane. In 1561 Motoyasu ordered the capture of Kaminojo, an endeavor that served a number purposes. Firstly, it sent a clear message to Nobunaga that the Matsudaira had really and truly cut their ties to the Imagawa. Secondly, Motoyasu got his hands on two sons of the slain castle commander, Udono Nagamochi, which he used as barter with Ujizane. Perhaps due to the fact that the Udono were a important Imagawa retainer clan, Ujizane unwisely agreed to release Motoyasu’s family members in return for the Udono children. |~|

As soon as he was reunited with his wife and son, Motoyasu was free to make any moves we wished without hindrance. He defeated the militant Mikawa monto in March 1564 in a sharp encounter that saw him actually struck by a bullet that failed to penetrate his armor. Soon afterwards he began testing the Imagawa defenses in Tôtômi. Having thus begun to make a name for himself, in 1566 he petitioned the court to allow him to change his name to Tokugawa, a request that was granted and so from this point he became known as Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Tokugawa Ieyasu and Oda Nobunaga

Tokugawa, Nobunaga territory

Though the Tokugawa could claim some modicum of freedom, they were very much subject to the requests of Oda Nobunaga. When Oda marched on Kyoto in 1568, Tokugawa troops were present, the first of many joint Oda-Tokugawa ventures. In June of 1570, Ieyasu led 5,000 men to help Nobunaga win the Battle of Anegawa against the Asai and Asakura, a victory owed largely to the efforts of the Tokugawa men. [Source: Samurai Archives]

In 1575 the warlord Takeda Katsuyori surrounded Nagashino Castle in Mikawa, and when word reached Ieyasu, he called on Nobunaga for help. When the latter dragged his feet on the matter, Ieyasu went as far as to threaten to JOIN the Takeda and spearhead an attack on Owari and Mino. This was the sort of talk that Nobunaga respected, and he immediately led an army into Mikawa. The combined Oda-Tokugawa force of some 38,000 crushed the Takeda army on 28 June but did not vanquish it. Katsuyori continued to bother the Tokugawa afterwards, and the Takeda and Tokugawa raided one another’s lands frequently.

In 1579 Ieyasu’s eldest son, Hideyasu, and his wife were accused of conspiring with Takeda Katsuyori. Due in part to pressure from Nobunaga, Ieyasu ordered his son to commit suicide and had his wife executed. Like his late rival, Takeda Shingen, Tokugawa was known to run hot and cold, and could be utterly merciless when the overall fortunes of his clan were at stake. He would in time name his 3rd son, Hidetada, as heir, since his second was to be adopted by Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

in Spring 1582 the Tokugawa joined Nobunaga in finally invading and destroying the Takeda and for his efforts Ieyasu received Suruga province, an acquisition which must have brought him no small private satisfaction. He now bordered the Hôjô, and cautiously sounded them out, his efforts helped in part by a personal friendship from his hostage days in Sumpu, Hôjô Ujinori, bother of the daimyo, Ujimasa.

Ieyasu was staying in Sakai (Settsu province) when Nobunaga was killed by Akechi Mitushide in June 1582 and narrowly escaped with his own life back to Mikawa. The Tokugawa were not in a position to challenge Mitsuhide, but did take advantage of the uncertainty following the Battle of Yamazaki to take Kai and Shinano, a move that prompted the Hôjô to send troops into Kai; no real fighting occurred, and the Tokugawa and Hôjô made peace. Ieyasu gave some of his lands in Kai and Shinano to the Hôjô, though found himself embarrassed in this respect by Sanada Masayuki the following year. In the meantime, Ieyasu readily availed himself of the example of government left behind by Takeda Shingen and was quick to employ surviving Takeda men within his own retainer band. He avoided becoming involved in the conflict between Shibata Katsuie and Toyotomi Hideyoshi that culminated in the Battle of Shizugatake (1583), but became aware that sooner or later Hideyoshi would come to test his own resolve.

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Rise to Power

As soon as Hideyoshi died, the leading daimyo began eyeing each other with suspicion and jockeying for strategic advantage. At that time, the most powerful of the five leaders was Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was based as Fushimi Castle and the leader of the Eastern Army. The second most powerful was Ishida Mitsunari, based at Osaka Castle and leader of the Western Army and loyal to Hideyoshi’s heir.

A decisive battle took place in 1600. Suspicious of Ieyasu’s lust for power Mitsunari fomented a rebellion in Ieyasu’s territory, forcing Ieyasu to leave Fushimi with the greater part of his army. Fushimi Castle was left under the command of Torii Mototada and a force of 1,800 samurai. On July 16, Mitsunari besieged the castle with a 40,000-man army. Mototada’s force held on for two weeks but was reduced to only 380 men.

Battle of Sekigahara

On August 1, 1600, a fire was set inside the castle, perhaps by a ninja. Some of Mitsunari’s soldiers managed to enter the castle and surround the 380 samurai. Rather than give up Mototada order his enemies to chop of his head, which they in full view of the 380 samurai, who then followed their leader’s example and committed seppuku (ritual suicide). The fall of Fushimi encouraged other leaders to join Mitsunari. Their combined force met Ieyasu’s army on September 15 at Sekigahara, 60 miles northwest of Kyoto.

The Battle of Sekigahara on October 21, 1600 is one of the most important battles in Japanese history. The Eastern Army of Ieyasu faced off against the Western Army of Mitsunari. Each army contained more than 80,000 men. The Eastern Army of Ieyasu routed the Western Army of Mitsunari, paving the way for Ieyasu to claim the Shogunate. Ieyasu won the day by employing some underhanded trickery. He convinced a Western Army general to switch sides at the last minute. Samurai under the general’s command attacked the Western Army from the rear, causing it to fragment and open itself to attacks from the Eastern Army. Today a plinth marks the spot where Ieyasu’s generals presented him with thousands of heads. Three years later Ieyasu was given the title of shogun.

Tokugawa Ieyasu Unifies Japan and Firms His Grip on Power

After Tokugawa Ieyasu’s decisive victory he was the most powerful person in Japan. Ieyasu was more than an excellent general. He was also a shrewd politician and institution builder. In the course of capitalizing on his victory, Ieyasu established a strong and stable bakufu that ruled Japan until the 1860s. The period from 1603, the date Ieyasu formally took the title of shogun, until the last shogun’s resignation in 1867, is known as the Tokugawa period or Edo period.

Tokugawa Ieyasu was willing to sacrifice his own family members to firm his grip on power. In the 1570s, he discovered through intercepted letters that his wife was conspiring against his peace pact with his brutal military rival, Oda Nobunaga. Given the choice of murdering his wife and son or fighting a civil war, Ieyasu chose the former. His wife, who was viewed as traitor, was dispatched by an assassin. A few months later he forced his son to commit suicide.

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu took the title shogun. As the most powerful person in Japan, he could have taken any title he wanted. In contrast with Hideyoshi, Ieyasu had many children by his various wives and concubines. Ieyasu selected his son Hidetada to succeed to the position of shogun and then "retired" to rule from behind the scenes--in what by now should be a very familiar style of exercising power in Japan. By retiring, Ieyasu was able to ensure a smooth transition and succession between himself and his son. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Siege of Osaka Castle in 1615

“Perhaps the most important step in solidifying the power of his family was for Ieyasu to eliminate the only other person in Japan with a possible claim to legitimacy as ruler. This person was Hideyoshi’s son, Hideyori, now a young man. Hideyori, was, of course, the one Ieyasu and other leading daimyo had sworn to the dying Hideyoshi that they would forever protect. Hideyori resided in Osaka castle and had with him a force of warriors hostile to Tokugawa Ieyasu. In 1614, Ieyasu launched an attack on Osaka castle, which lasted into 1615. In the end, all inside, including Hideyori, were slaughtered.” ~

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Rule

Ieyasu became shogun in 1603. Under his leadership hereditary daimyos and samurai monopolized the government, a balance of power was created among Japans 250 daimyos and an urban merchant class controlled commerce. Unlike the preceding centuries, which were dominated by civil war, peace prevailed and literacy spread and the arts blossomed in a cultural golden age for Japan.

During Ieyasu’s rule Neo-Confucianism, and it hierarchal ordering of society, became part of the national ideology. Society was divided along strict class lines between samurai, peasants, merchants and artisans. The Tokugawa family took control of the large estates, major cities, ports and mines. Merchants, craftsmen, farmers, and samurai all served the shogun and great castles were constructed for defense. The powerless emperor and the imperial court continued to de isolated in Kyoto.

Like Hideyoshi, Ieyasu encouraged foreign trade but also was suspicious of outsiders. He wanted to make Edo a major port, but once he learned that the Europeans favored ports in Kyushu and that China had rejected his plans for official trade, he moved to control existing trade and allowed only certain ports to handle specific kinds of commodities.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Samurai and Buddhists

According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: In 1612, Hidetada issued a decree prohibiting Christianity in Japan. In Hideyoshi’s day, nearly one percent of Japan’s population had become Christian, at least nominally. When Christianity, in the form of Roman Catholicism, first came to Japan, most Japanese regarded it as a form of Buddhism. Recall that for Mahayana Buddhists, nearly anything can be and is Buddhism. As time went on, however, Japan’s leaders, starting with Hideyoshi, became uneasy about the potential political power of Christianity. Many regarded Christianity as similar to the militant sects of Buddhism that Oda Nobunaga had so recently destroyed. The Tokugawa shoguns saw that Catholicism and Spanish and Portuguese military expansion throughout the globe seemed to go hand-in-hand. The bakufu ban on Christianity, therefore, was based in part on fears of its potential for causing internal political unrest. It was also based on fear that Christianity might help pave the way for an external invasion by Spain or Portugal. The bakufu banned certain militant forms of Buddhism around this time for similar reasons. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

“Tokugawa bakufu was actually the beginning of the end of the age of warrior predominance in society, at the dawn of the Tokugawa period the warrior seemed central to any social order. The founding premise of the Tokugawa bakufu was, therefore, that he who controls the warriors controls all of Japan. The bakufu’s early institutional development reflected this premise. ~

“After the victory at Osaka Castle in 1615, the bakufu issued Laws for Warrior Households (Buke shohatto). These laws applied to all members of the samurai class, whether in the direct service of the Tokugawa family or otherwise. The laws were a mixture of vague moral exhortations (e.g., to lead a frugal and simple life), unlikely to be enforceable, and specific restrictions or requirements. Many items, such as the restrictions on castle construction and marriages, were intended to weaken the power of the daimyo vis-à-vis the bakufu. These laws established the basic framework of the relationship between the daimyo--who continued to exist throughout the Tokugawa period--and the bakufu. In 1629, the bakufu issued a revised version of the Laws for Warrior Households, and they underwent several more revisions during the next century. ~

Some of the Laws for Warrior Households included: 1) The arts of peace and war, including archery and horsemanship, shall be pursued single-mindedly. 2) Drinking parties and wanton revelry are to be avoided. 3) Offenders against the law shall not be harbored or hidden in any domain. 4) Whenever one intends to make repairs on a castle of one of the domains, bakufu authorities should be notified. All construction of new castles is to be stopped and never resumed. 5) Immediate report should be made of innovations which are being planned or factional conspiracies being formed in neighboring domains. 6) Do not enter into marriage privately [i.e., without notifying bakufu authorities]. 7) Visits of the daimyo to the capital are to be in accordance with regulations [regarding the total number of escorting samurai and related matters]. 8) The samurai of the various domains shall lead a frugal and simple life. ~

Tokugawa Ieyasu on Military Government and the Social Order

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ Creating the Tokugawa system of rule required a variety of sweeping political and social reforms, none perhaps with a more profound impact than the division of society into four hereditary status groups (often called classes) based on occupation, known in Japanese as the “shinōkōshō “(samurai, peasants, artisans, merchants). In this short document, written by an unidentified retainer in the early seventeenth century, Ieyasu’s conception of the Tokugawa social hierarchy is recorded. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

The Military Government and the Social Order by Tokugawa Ieyasu reads: “Once, Lord Tōshō [Ieyasu] conversed with Honda, Governor Sado, on the subject of the emperor, the shogun, and the farmer. “Whether there is order or chaos in the nation depends on the virtues and vices of these three. The emperor, with compassion in his heart for the needs of the people, must not be remiss in the performance of his duties — from the early morning worship of the New Year to the monthly functions of the court. [Source: “Korō shodan,” in “Dai.Nihon shiryō,” Part 12, Vol. 24, pp. 546-549; “Sources of Japanese Tradition”, edited by Ryusaku Tsunoda and Wm. Theodore de Bary, 1st ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1964), 329-330.

“Secondly, the shogun must not forget the possibility of war in peacetime, and must maintain his discipline. He should be able to maintain order in the country; he should bear in mind the security of the sovereign; and he must strive to dispel the anxieties of the people. One who cultivates the way of the warrior only in times of crisis is like a rat who bites his captor in the throes of being captured. The man may die from the effects of the poisonous bite, but to generate courage on the spur of the moment is not the way of a warrior. To assume the way of the warrior upon the outbreak of war is like a rat biting his captor. Although this is better than fleeing from the scene, the true master of the way of the warrior is one who maintains his martial discipline even in time of peace.

“Thirdly, the farmer’s toil is proverbial — from the first grain to a hundreds acts of labor. He selects the seed from last fall’s crop, and undergoes various hardships and anxieties through the heat of the summer until the seed grows finally to a rice plant. It is harvested and husked and then offered to the land steward. The rice then becomes sustenance for the multitudes. Truly, the hundred acts of toil from last fall to this fall are like so many tears of blood. Thus, it is a wise man who, while partaking of his meal, appreciates the hundred acts of toil of the people.

“Fourthly, the artisan’s occupation is to make and prepare wares and utensils for the use of others. Fifthly, the merchant facilitates the exchange of goods so that the people can cover their nakedness and keep their bodies warm. As the people produce clothing, food and housing, which are called the ‘three treasures’, they deserve our every sympathy.”

Edicts of the Tokugawa Shogunate: Laws of Military Households, 1615

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The unification of Japan and the creation of a lasting national polity in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries required more than just military exploits. Japan’s “three unifiers,” especially Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536- 1598) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), enacted a series of social, economic, and political reforms in order to pacify a population long accustomed to war and instability and create the institutions necessary for lasting central rule. Although Hideyoshi and Ieyasu placed first priority on domestic affairs — especially on establishing authority over domain lords, warriors, and agricultural villages — they also dictated sweeping changes in Japan’s international relations. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“Although the Tokugawa shogunate proved a durable political system, it lacked the elaborate legal codes and sophisticated bureaucratic apparatus of the Chinese imperial state. One of the most important Tokugawa legal documents, the Laws of Military Households (“Buke Shohatto”), was issued in 1615, only one year before Tokugawa Ieyasu’s death, and provided basic regulations on the behavior of lords and warriors.”

Excerpt from “Laws of Military Households, 1615" (Buke Shohatto) edict issued on the First year of Genna [1615], seventh month: 1) The study of literature and the practice of the military arts, including archery and horsemanship, must be cultivated diligently. On the left hand literature, on the right hand use of arms,” was the rule of the ancients. Both must be pursued concurrently. Archery and horsemanship are essential skills for military men. It is said that war is a curse. However, it is resorted to only when it is inevitable. In time of peace, do not forget the possibility of disturbances. Train yourself and be prepared. [Source: “Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period”, edited by David J. Lu (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe, 1997), 206-208]

2) Avoid group drinking and wild parties... 6) The castles in various domains may be repaired, provided the matter is reported without fail. New construction of any kind is strictly forbidden...8) Marriage must not be contracted in private [without approval from the “bakufu”]... To form a factional alliance through marriage is the root of treason.

10) The regulations with regard to dress materials must not be breached. Lords and vassals, superiors and inferiors, must observe what is proper within their positions in life. Without authorization, no retainer may indiscriminately wear fine white damask, white wadded silk garments, purple silk kimono, purple silk linings, and kimonosleeves which bear no family crest.

12) The samurai of all domains must practice frugality. When the rich proudly display their wealth, the poor are ashamed of not being on par with them. There is nothing which will corrupt public morality more than this, and therefore it must be severely restricted.

13) The lords of the domains must select as their officials men of administrative ability. The way of governing a country is to get the right men. If the lord clearly discerns between the merits and faults of his retainers, he can administer due rewards and punishments. If the domain has good men, it flourishes more than ever. If it has no good men, it is doomed to perish. This is an admonition which the wise men of old bequeathed to us. Take heed and observe the purport of the foregoing rules.

After Tokugawa Ieyasu

Ieyasu died in 1616. He was reburied at Mt. Nikko, a sacred mountain traditionally visited by military leaders. According to “Topics in Japanese Cultural History”: His death caused no particular problems, however, for Hidetada had become well-acquainted with the office of shogun and continued his father’s work of creating a strong bakufu under the Tokugawa family. Like his father, Hidetada also "retired" while in good health. In 1623, he handed the office of shogun over to his son Iemitsu, further establishing the Tokugawa family’s hold over the highest office in the land. Tokugawa Ieyasu and his sons were not scholars, but they had a basic understanding of history. They learned from the examples of Hideyoshi and, much earlier, Minamoto Yoritomo. They worked to ensure that power would remain in Tokugawa hands well into the future. To this end, they created stable, viable institutions and also devoted attention to bolstering the religious-symbolic authority of the Tokugawa house. [Source: “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~]

Tokugawa rulers continued to rule after Ieyasu. By the time of Tokugawa Iemitsu’s death 1651, the bakufu had become firmly established in power, and the Tokugawa family was firmly in control of the bakufu. It was no longer necessary for shoguns to retire in favor of their sons.

Japanese society of the Tokugawa period was influenced by Confucian principles of social order. At the top of the hierarchy, but removed from political power, were the imperial court families at Kyoto. The real political power holders were the samurai, followed by the rest of society. In descending hierarchical order, they consisted of farmers, who were organized into villages, artisans, and merchants. Urban dwellers, often well-to-do merchants, were known as chonin (townspeople) and were confined to special districts. The individual had no legal rights in Tokugawa Japan. The family was the smallest legal entity, and the maintenance of family status and privileges was of great importance at all levels of society.

Image Sources: JNTO, Tokyo National Museum, Samurai Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Samurai Archives samurai-archives.com; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek, Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2016