JAVA

Java is the world's most populous island and the center of Indonesia culture, politics and economic life. Historical events that took place here shaped Indonesia as a whole. Outsiders still seek it out as the place to make one’s name and seek fame and fortune in the archipelago. It is an incredibly rich place, with a rich cultural traditions and places of extraordinary beauty that are not marred by island’s dense masses, noise and traffic. It is about a third the size of California but has more than three times the people.

Altogether, some 150 million people live on Java, about half the population of Indonesia. Of these about two thirds are Javanese. It is surprising that so many people live on Java, which occupies an area smaller than New York State and makes up only 6.9 percent of Indonesia. Some areas of Java have the highest rural densities in the world, with an average density of 4,145 people per square kilometer (1,600 people per square mile) . Some areas it is much higher. Around the rural area of Modjokuto densities of 15,400 to 20,720 people per square kilometer (6,000 to 8,000 people per square mile) were recorded in 1969. Jakarta is now recognized as the world's largest city.

Because Java is so densely populated the rural areas have a urban quality to them.. Villages are often only a few hundred meters apart and usually no more than eight kilometers separates towns. The only cities with a true urban and industrial character are Jakarta, Surubaja and Semarang. Population growth combined with small and fragmented land holdings produce severe problems such as overcrowding and poverty.

RELATED ARTICLES:

CENTRAL JAVA factsanddetails.com

EAST JAVA factsanddetails.com

Javanese

The Javanese are Indonesia’s and Southeast Asia's largest ethnic group and the third largest Muslim ethnic group in the world following Arabs and Bengalis. They live primarily in the provinces of east and Central Java but are found throughout Indonesia’s islands. “Wong Djawa” and “Tijang Djawi” are the names that Javanese use to refer to themselves. The Indonesian term for them is “Ornag Djawa.” The word Java is derived from the Sanskrit word “yava”, meaning “barely, grain.” The name is very old and appeared in Ptolemy’s “Geography”, from Roman Empire of the A.D. 2nd century. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The majority of Javanese llive in Jawa Timur and Jawa Tengah provinces; most of the rest live in Jawa Barat Province and on Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and other islands. Altogether, some 150 million people live on Java, about half the population of Indonesia. Although many Javanese express pride at the grand achievements of the illustrious courts of Surakarta and Yogyakarta and admire the traditional arts associated with them, most Javanese tend to identify not with that elite tradition, or even with a lineage or clan, but with their own village of residence or origin. These villages, or desa, are typically situated on the edge of rice fields, surrounding a mosque, or strung along a road.

There are over 100 million Javanese, Javanese people make up 40 percent to 45 percent of the total population of Indonesia, with figures around 40.2 percent to 42.65 percent being the most commonly cited in recent data. The Sundanese are the next largest group, making up about 15 percent of Indonesia’s population. The Javanese population was approximately 2 million in 1775. In 1900, the population of the island of Java was around 29 million, In 1990, the population of Java and the small island of Madura was estimated to exceed 109 million. At that time, Jakarta, the capital city, had a population of about 9.5 million. The combination of population growth and small, fragmented landholdings has produced severe overcrowding and poverty. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Google AI]

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVANESE PEOPLE: HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE RELIGION: ISLAM, MYSTICISM, FESTIVALS, BELIEFS, PRACTICES factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE CULTURE: MUSIC, SHADOW PUPPETRY, FOLKLORE, LITERATURE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, GENDER, CUSTOMS, CLASSES factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE LIFE: VILLAGES, HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

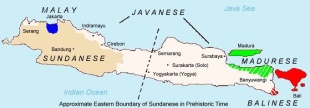

Sundanese

The Sundanese hail from western Java but are found throughout Indonesia. Also known as the Orang Sunda, Urang Prijangan, Urang Sunda, they are culturally similar to the Javanese but regard themselves as less formal, more soft spoken and lighter hearted than Javanese. Sundanese make up 15.5 percent of the population of Indonesia and are the second largest ethnic group after the Javanese. They have their own distinct culture and speak their own language, which requires speaker to adjust their speech and vocabulary to accommodate the status and intimacy of the person they talk to. Nearly all are Muslims. The Sundanese homeland is the Priangan Highlands of West Java, an area they call “parahyangan” (“paradise”). [Source: David Straub,, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Sundanese (pronounced sun-duh-NEEZ) had their own state—the kingdom of Pajajaran (1333-1579)—but mostly they have been dominated by Javanese kingdoms while remaining somewhat isolated and keeping alive their own traditions. Islam was introduced by Indian traders in the 15th century and spread inland from the ports, where Indians traded. The nobility was forced to convert to Islam in1579 after the existing royal family was killed by the sultan of Bantem. The Dutch introduced coffee plantation agriculture. The Sundanese both cooperated with and resisted the Dutch. Some Sundanese pursued a Western education and became civil servants. Others fought two holy wars against the Dutch: one in the 1880s and another after World War II.

The homeland of the Sundanese — Sunda — is western Java (Jawa Barat) as far east as the Cipamali river. The name "Sunda" comes from Sanskrit, meaning "shining" or "pure," reflecting a connection to ancient kingdoms like Tarumanagara some sources say. Other sources say Sundal comes from an ancient volcano, Mount Sunda, that appeared in early geographical texts (Ptolemy, 150 AD). . Sundaland is a vast, sunken landmass in Southeast Asia that connected Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula during glacial periods when sea levels were lower, creating a large, exposed continental shelf. The Sundanese people are believed to have originated from or migrated across this ancestral Sundaland.

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUNDANESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, LANGUAGE, POPULATION factsanddetails.com

SUNDANESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, GENDER factsanddetails.com

SUNDANESE LIFE: VILLAGES HOUSES, FOOD, WORK factsanddetails.com

SUNDANESE CULTURE: FOLKLORE, MUSIC, SHADOW PUPPETRY factsanddetails.com

WEST JAVA: ANCIENT HISTORY, GUNUNG PADANG, SUNDANESE CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Baduy

The Baduy are one of the most unusual groups in Indonesia. Nobody really knows anything about them. Their villages are closed to outsiders especially during their sacred rituals. Practically the only thing they eat is rice and they seem to spend most of their time communicating with spirits. They are throught to have retreated to the mountains when Islam came to their homeland and they fled there to keep their religious customs alive. Generals and politicians sometimes seek them out for their perceived ability to see into the future. [Source: Harvey Arden, National Geographic, March 1981]

Ed Davies of Reuters wrote: “Despite their proximity to the Indonesian capital, the Baduy might as well be a world away as they live in almost complete seclusion, observing customs that forbid using soap, riding vehicles and even wearing shoes. Within a 50 square kilometers (20 square mile) area in the shadow of Mount Kendeng, the Baduy people cling to their reclusive way of life despite the temptations of the modern world. No one is certain of their origin. Some anthropologists think they are the priestly descendents of the West Java Hindu kingdom of Pajajaran and took refuge in the limestone hills where they now live after resisting conversion to Islam in the 16th century. They speak an archaic version of Sundanese, a language spoken by many in this part of western Java.” [Source: Ed Davies, Reuters, November 27, 2008]

The Baduy (also spelled Badui) call themselves Urang Kanekes—urang meaning “people” in Sundanese and Kanekes referring to their sacred homeland. They live in the western part of Indonesia’s Banten Province, near Rangkasbitung. Estimates of their population range from about 5,000 to 11,700, depending on how they are counted. Most Baduy communities are concentrated in the Kendeng Mountains at elevations of 300–500 meters above sea level. Their homeland covers roughly 50 square kilometers of hilly forest, about 120 kilometers from Jakarta. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: BADUY factsanddetails.com

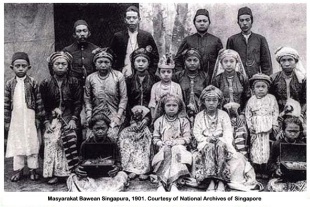

Baweanese

The Baweanese live on Bawean Island, north of Java. Also known as the Bawean Islanders, Boyanese, Orang Boyan, Orang Babian, Orang Bawean, and Orang Boyan, they are closely related to the Madurese, hail from Madura island and speak a language closely related to Madurese but regard themselves as a distinct ethnic group. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Around 84,000 Baweanese were counted in 2010 census, up from 60,000 in the early 1990s. They are fishermen and rice and corn farmers. Mat weaving, once an important and highly developed craft, has declined in significance. Historically, Bawean Island was a trading post and hub for maritime activities. This brought influences from various cultures, including Javanese, Madurese, Banjarese, Makassarese, Chinese, and Arab. Consequently, the Bawean people have a rich cultural heritage blending elements from these diverse

The Baweanese are Sunni Muslims and are known for their strict observance of religious practices. In the past men were known for leaving the island to work — a tradition known as merantau — often to Singapore and the west coast of Malaysia. Traditionally they used the money they made for Hajj pilgrimages to Mecca but that no longer is the case. Today they work to make money for themselves and their families and sometimes bring their families along on the Hajj Today, entire families often migrate, with the Riau Archipelago south of Singapore becoming a major destination. .

The ancestors of the Baweanese migrated to the island from Madura at the end of the fourteenth century. In addition to the Baweanese, Bawean island is home to smaller groups such as the Diponggo, Bugis, and Kema, all of whom have largely been assimilated into Baweanese society. Madurese migrants, by contrast, have remained socially separate and are now economic competitors of the Baweanese.

Tenggerese

The Tenggerese are a Javanese people who live around Mt. Bromo in the Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park in eastern Java. Tracing their ancestry back of 14th century princes connected to the Majapahit Empire, they still practice their own religion, a mix of Hinduism, animism and volcano worship. The Tenggerese fled to the Bromo area to escape the surge of Islam that occurred after the collapse of the Majapait Empire in the 16th century. They speak an archaic Javanese (Majapahit) dialect called Tengger Javanese. They have their own written Kawi script based on the old Javanese Brahmi type. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993); indonesia.travell Wikipedia]

The Tenggerese live in the highlands of the Tengger mountains (Mount Bromo). Mt. Bromo is sacred to the Tenggerse. Periodically they make offerings of animals, meat and vegetables to ensure the volcano remains calm. Sometimes when the volcano starts to rumble, the local population doesn't try to escape, instead they go to the top to make offerings to placate the volcano God.

Despite the Islamization of most of Java, the Tenggerese have retained religious practices rooted in the Majapahit past. Like Balinese Hindus, they worship Ida Sang Hyang Widi Wasa as the supreme deity, alongside the Trimurti—Shiva, Brahma, and Vishnu—while also incorporating animist beliefs and elements of Mahayana Buddhism. Their ritual spaces include punden, danyang, and especially the poten, a sacred ritual complex located in Bromo’s “sea of sand.” The poten becomes the focal point of the annual Kasada Ceremony, during which offerings are cast into the volcano.

Ancestor worship is also central to Tengger belief. Spirits include cikal bakal (village founders), roh bahurekso (guardian spirits), and roh leluhur (ancestral spirits). Specialized priests conduct rites in which small doll-like figures representing these spirits are dressed in batik and presented with food and drink; the spirits are believed to consume the spiritual essence of the offerings.

Economically, the Tenggerese are mainly agriculturalists and herders. Farmers generally occupy lower elevations, while nomadic or semi-nomadic herders live higher in the mountains, often traveling on small horses. In recent decades, population pressure from neighboring Madura has led to settlement, land clearing, and limited religious conversion in more accessible lowland areas. In response, many Hindu Tenggerese sought support from Balinese Hindus, reformulating aspects of their religion and ritual life to strengthen their identity. Government designation of the Bromo–Tengger–Semeru area as a national park has since restricted logging and helped protect the Tenggerese homeland from further disruption.

Yadnya Kasada — the Tenggerese Mt. Bromo Volcano Ritual

The Yadnya Kasada is a festival held in the month of Kasada on the traditional Hindu lunar calendar that honors Sang HyangWidhi, the God Almighty, Roro Anteng, daughter of King Majapahit, and Joko Seger, son of Brahmana. On the fourteenth day of Kasada — usually around November or September — the native people of the area, the Tenggerese, gather at the rim of Mount Bromo's active crater to present offerings of rice, fruit, vegetables, flowers, livestock and other local produce to the God of the Mountain. The Tenggerese are adherents of a religion which combines elements of Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. In this Kasada ceremony the Tenggerese ask for blessing from the supreme God, Sang Hyang Widi Wasa.

One month before the Yadnya Kasada Day, Tenggerese from numerous mountainous villages scattered across the area will gather at the Luhur Poten Temple at the foot of Mount Bromo. One distinct feature that sets the Luhur Poten Temple apart from other Hindu temples in Indonesia is that it is constructed from natural black stones from the nearby volcanoes, while Balinese temples are usually made from red bricks. These temple ceremonies are prayers to ask for blessings from the Gods, and often last long into the night. [Source: indonesia.travel]

When the Yadnya Kasada day arrives, the crowds that have travelled together up the mountain, throw offerings into the crater of the volcano. These sacrifices include vegetables, fruit, livestock, flowers and even money, and are offered in gratitude for agricultural and livestock abundance. Despite the evident danger, some locals risk climbing down into the crater to retrieve the sacrificed goods, believing that they will bring good luck.

The origin of this ritual stems from an ancient legend of a princess named Roro Anteng and her husband Joko Seger. After many years of marriage, the couple remained childless, and therefore meditated atop Mount Bromo, beseeching the mountain gods for assistance. The gods granted them 24 children, under the condition that the 25th child must be thrown into the volcano as human sacrifice. The gods’ request was observed, and so the tradition of offering sacrifices into the volcano to appease the deities continues until today, although instead of humans, chickens, goats and vegetables are thrown into the crater for sacrifice.

Describing the event in 2014, NBC reported: Tenggerese worshippers trek across the "Sea of Sand" to give their offerings during the Yadnya Kasada Festival at crater of Mount Bromo on Aug. 12, 2014, in Probolinggo, East Java, Indonesia. The main festival of the Tenggerese people, Kasada lasts for about a month, and on the 14th day the Tenggerese journey to Mount Bromo. There they make offerings of rice, fruits, vegetables, flowers and livestock to the mountain gods by throwing them into the volcano's caldera. [Source: nbcnews.com]

1) A Tenggerese worshipper carries his son as he climbs Mount Bromo to collect holy water during the Tenggerese Hindu Yadnya Kasada festival on Aug. 11. 2) Tenggerese worshippers prepare a chicken for offering to the Tenggerese shaman as they pray at Widodaren cave on Aug. 11. 3) Tenggerese worshippers collect holy water at Widodaren cave on Aug. 11. 4) Tenggerese worshippers trek across the "Sea of Sand" with a goat for offering at the crater of Mount Bromo on Aug. 12. 5) Non-Hindus carry nets as they wait on the edge of the crater to catch offerings cast down by Hindus during the Kasada ceremony at Mount Bromo, on Aug. 12. The ceremony is a way for Tengger Hindus to express their gratitude to God for good harvest and fortune. The offerings include vegetables, chickens, fruits, goats, money and other valuables. 6) A bird is thrown by Hindu worshippers over the crater of Mount Bromo during the Yadnya Kasada Festival on Aug. 12. 7) A Tenggerese worshipper carries vegetables for offerings at the crater of Mount Bromo on Aug. 12. 8) A Tengger tribesman prays at Mount Bromo during the annual Kasada ceremony in East Java on Aug. 12.

Betawi — The Mixed Race People of Jakarta

The Betawi people — also known as Batavians and Orang Betawi (meaning “people of Batavia”) — are an Austronesian ethnic group native to Jakarta and its surrounding areas. They are generally regarded as the original inhabitants of the city and descend from the diverse populations who lived in Batavia from the 17th century onward. [Source: Wikipedia, Indonesia Tourism website]

The term Betawi emerged in the 18th century, reflecting the gradual blending of many ethnic groups brought together in Batavia during the Dutch colonial period. These included local Javanese and Sundanese populations as well as migrants and settlers from across the archipelago and beyond. In the modern era, people of various backgrounds—particularly Sundanese who have long lived in Greater Jakarta and gradually shifted away from the Sundanese language—may also identify as Betawi. By ancestry, however, they may be closer to Sundanese-speaking communities that remain in surrounding regions such as Bekasi, Bogor, and Tangerang.

Most Betawi are Sunni Muslims. Some are Christians. Of these some trace their origins to the Portuguese Mardijker community, which intermarried with local populations and settled in areas such as Kampung Tugu in North Jakarta. As a result, Betawi culture—often popularly associated with Islam—also incorporates Christian Portuguese and Chinese Peranakan influences alongside its indigenous roots.

The Betawi language, commonly called Betawi Malay, is a Malay-based creole. Historically, it was the only Malay-derived language spoken along Java’s northern coast, a region otherwise dominated by Javanese dialects, with some areas using Madurese or Sundanese. Betawi vocabulary contains numerous loanwords from Hokkien Chinese, Arabic, and Dutch. Today, Betawi Malay functions as a widely used informal speech variety in Indonesia and forms the basis of much Indonesian slang, making it one of the country’s most dynamic and widely spoken local dialects.

Origin of the Betawi

Jakarta is a highly multicultural city, home to Indonesians from across the archipelago as well as a large Chinese community and many expatriates. The Betawi, are among Indonesia’s most recently formed ethnic groups. They emerged as a creole people through centuries of mixing among local groups—especially Sundanese and Javanese—and migrants from China, Arabia, Portugal, and the Netherlands. [Source: Wikipedia, Indonesia Tourism website]

The roots of Betawi society lie in the 17th century, when the Dutch destroyed Jayakarta and rebuilt it as Batavia under the VOC. To serve colonial trade interests, Batavia was repopulated with slaves, free Asians, Chinese workers, Christian converts from former Portuguese settlements, and a small Dutch elite. Early residents were identified by their ethnic origins and lived in separate enclaves (kampung), many of which survive today in place names such as Kampung Melayu and Kampung Bali.

By the late 19th to early 20th century, these diverse groups had merged into a distinct Malay-speaking community that came to call itself Betawi. Betawi culture and language differ from those of surrounding Sundanese and Javanese populations and are especially known for their music, food, and traditions.

After Indonesian independence and Jakarta’s designation as the national capital, migration from across the country accelerated. Although now reduced to smaller pockets within the expanding metropolis, the Betawi have maintained a strong cultural identity. Many traditionally lived as small landholders, and symbols such as the giant ceremonial dolls known as ondel-ondel remain enduring markers of Betawi heritage.

Betawai Culture

The Betawi are known for a direct, egalitarian style of speech and an open, humorous temperament, though they can be firm when challenged. Their culture and arts clearly reflect centuries of interaction with other peoples. Portuguese and Chinese influences are evident in Betawi music, while Sundanese, Javanese, and Chinese elements shape their dance traditions. Today, Betawi expressions and dialect are especially popular among Indonesian youth and are widely heard on television, making them familiar well beyond Jakarta. [Source: Wikipedia, Indonesia Tourism website]

Traditionally, Betawi were not city dwellers living in gedong (European-style buildings) or two-story Chinese rumah toko (shophouses) near the old city walls. Instead, they lived in kampung settlements surrounded by orchards on the outskirts of Batavia. Betawi houses typically follow one of three styles: rumah bapang (also known as rumah kebaya), rumah gudang (warehouse style), and the Javanese-influenced rumah joglo. Most feature gabled roofs, except the joglo, which has a tall, peaked roof. A distinctive decorative feature is gigi balang (“grasshopper teeth”), a row of wooden shingles along the roof fascia. Another hallmark is the langkan, an open front veranda where families welcome guests and carry out much of their daily social life.

Ritual and performance play an important role in Betawi society. Mangkeng is a ceremonial rite performed at major gatherings—especially weddings—to bring good fortune and ward off rain. It is led by a village shaman, known as the pangkeng. Betawi musical traditions such as gambang kromong, tanjidor, and keroncong Kemayoran derive in part from the keroncong music of Portuguese Mardijker communities in the Tugu area of North Jakarta. The well-known song “Si Jali-jali” is a classic Betawi tune.

Betawi weddings are often multi-day events, open to the entire community. Guests are entertained with music, dance, and film screenings that continue late into the night, sustained by simple refreshments like bananas, peanuts, and hot tea. The bride typically wears a red costume inspired by Chinese ceremonial dress, complete with tassels covering her face, while the groom’s attire reflects Arab and Indian influences.

Betawi folk theater, known as lenong, draws on urban legends, historical tales, and foreign stories adapted to everyday Betawi life. Another iconic tradition is ondel-ondel, large bamboo effigies with painted masks, related to masked dance forms such as Chinese-Balinese Barong Landung and Sundanese Badawang. Betawi dance costumes show both Chinese and European influences, while movements—such as those in the Yapong dance—blend Sundanese Jaipongan rhythms with a hint of Chinese style. The Topeng Betawi, or Betawi mask dance, is another enduring expression of Betawi performance culture.

Madurese

The Madurese are an ethnic group that hail from Madura, a dry, inhospitable island off the northeast coast of Java, and have traditionally made their living off the island. Also known as the Orang Madura, Tijang Madura and Wong Madura, they are regarded by many Indonesians with the same contempt leveled at gypsies in Europe. The Javanese call them “kasar” (“unrefined”). Madurese men are often identified with the clurit, a distinctive sickle-shaped knife that holds strong cultural meaning, and with traditional clothing marked by bold red-and-white stripes. These colors are traced to the naval banner of the Majapahit Empire, the eastern Javanese kingdom that once ruled Madura Island. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

The Madurese (pronounced MAHD-oo-reez) have traditionally worked as farmers, traders, livestock producers and fishermen. They have long been resistant to outsiders and their history has been defined by struggles with the Javanese. In 1677 the Madurese managed to seize the royal treasury of the Javanese Mataram kingdom and the Javanese needed the help of the Dutch to get it back. The adoption of Islam in the 16th century helped the Madurese unify as a people. The Dutch used the Madurese as mercenaries and tapped anti-Javanese feeling among the Madurese in their battles again the Javanese .

Despite their ancestral island lying only a short distance from Surabaya on Java, the Madurese have long maintained a cultural identity distinct from their Javanese neighbors. Their history is closely intertwined with Java’s, yet marked by repeated assertions of autonomy and difference. Madurese cuisine is well known in Indonesia and the Madurese are regarded as the inventors of satay and pencak silat, a traditional martial art. They are also known as the largest owners of traditional grocery shops in Indonesia and famous for Karapan sapi bull races. Historically, this group has played a pioneering role in classical Islamic movements in Indonesia. Pondok Pesantren have long served as key centers for Madurese Muslims to study and transmit Islamic learning, particularly forms rooted in Indonesian Islam.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MADURESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, DEMOGRAPHICS factsanddetails.com

MADURESE LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILES, CULTURE, BULL RACING factsanddetails.com

VIOLENCE AGAINST THE MADURESE IN BORNEO factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025