JAVANESE SOCIETY AND KINSHIP

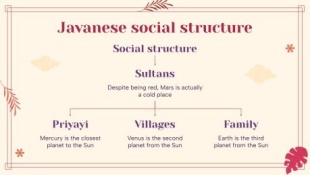

Javanese have traditionally lived under a fairly rigid class system with social classes that have deep historical roots. Under the Mataram Kingdom, peasants were governed by a landed nobility or gentry who represented the king. Land was distributed through an appanage system, granting rights to certain individuals in return for service. Merchants were concentrated in coastal and port towns, where international trade was dominated by Chinese, Indian, and Malay communities. These port towns were ruled by princes, and this basic social pattern continued into the early colonial era. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

During the colonial period, new social groups emerged alongside the peasantry. These included nonpeasant wage laborers and the prijaji, a class descended from the precolonial administrative elite. The prijaji filled white-collar and civil service positions, while a noble class (ndara) claimed direct descent from the rulers of the Mataram Kingdom.

In the twentieth century, Javanese society increasingly moved toward egalitarian ideals, with greater emphasis on social mobility. By the mid-twentieth century, peasants formed the largest social group, and a growing number of landless agricultural laborers had appeared.

Descent in Javanese society is bilateral, and the basic kin unit is the nuclear family (kulawarga). Two broader kinship groupings are also recognized. The golongan is an informal bilateral group, typically composed of relatives living in the same village who cooperate in ceremonies and celebrations. The alur waris is a more formal kin group responsible for maintaining ancestral graves.

Javanese kinship terminology follows four main principles. First, it is bilateral, using the same terms for relatives on the mother’s and father’s sides. Second, it is generational, grouping all members of the same generation under common terms. Third, it emphasizes seniority, distinguishing between older and younger relatives within a generation. Finally, it recognizes gender, with slight distinctions between close nuclear-family members and more distant kin.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVANESE PEOPLE: HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE RELIGION: ISLAM, MYSTICISM, FESTIVALS, BELIEFS, PRACTICES factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE CULTURE: MUSIC, SHADOW PUPPETRY, FOLKLORE, LITERATURE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE LIFE: VILLAGES, HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL JAVA factsanddetails.com

EAST JAVA factsanddetails.com

Javanese Classes and Social and Political Organization

In the precolonial Javanese kingdoms, the elite consisted of the descendants of rulers, known as the ningrat or priyayi. During the colonial era, however, the meaning of priyayi expanded to include all educated people, particularly those employed in white-collar occupations, regardless of noble ancestry. This group was distinguished from the wong cilik (“little people”), a category that included peasants and laborers. Alongside these groups was a separate santri elite, made up of ulama (Islamic scholars), their students, and merchants. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Peasant society also had its own internal hierarchy. At the top were the wong baku, householders and descendants of village founders. Below them were the kuli gandok, married men who continued to live with their parents, followed by joko or sinoman, unmarried men residing with parents or other households. Each village was headed by a lurah—also known as a petinggi, bekel, or glondong—who was elected by the villagers and granted the right to use communal land to support himself and his staff. Villagers cooperated in collective labor for projects such as building and maintaining roads, bridges, and public buildings, as well as in village-wide spiritual cleansing rites (bersih desa).

Administratively, Java is divided into three provinces (propinsi), along with the Special Region of Yogyakarta (Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta), which has provincial status. Each province is subdivided into five residencies (karésidènen), each residency into four or five districts (kawédanan), and each district into four or five subdistricts (katjamatan). Subdistricts contain between ten and twenty village complexes, known as kalurahan in Javanese or desa in Indonesian. The smallest administrative unit is the dukuhan, with each kalurahan comprising two to ten such units. Some dukuhan include several smaller villages or hamlets, also called desa. The kalurahan or desa is headed by a lurah, while each dukuhan is led by a kamitua.

Javanese Customs and Social Relations

The Javanese avoid confrontation at all costs. They respond to disturbing news with a resigned smile and gentle words. They never directly refuse any request, but they are very good at giving and taking hints. Proper respect also requires appropriate body language, such as bowing and slow, graceful movements. Children who have not yet learned to behave in a dignified manner are said to be durung Jawa, meaning "not yet Javanese." [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In rural areas, the neighborhood exerts the greatest pressure toward conformity with social values. The strongest sanctions are gossip and shunning. Family seems to exert less force than the neighborhood in exerting social control. The Javanese say that children who have not yet learned to control their emotions and behave respectfully and dignified are durung jawa, or "not yet Javanese." The ideal state for individuals and society is uneventful tranquility.

In Javanese society, interpersonal conflict, anger, and aggression are repressed or avoided. It is difficult to express differences of opinion in Java. Direct criticism, anger, and annoyance are rarely expressed. The primary method of resolving interpersonal conflicts is to stop speaking to one another (satru). This type of conflict resolution is not surprising in a society that represses anger and the expression of true feelings. The concern with maintaining peaceful interactions results not only in the avoidance of conflict and repression of true feelings but also in the prevalence of conciliatory techniques, particularly in status-bound relationships. One source of antagonism is the conflict between adherents of different religious orientations. This conflict is related to class differences between priyaji and abangan villagers (see "Religious Beliefs") and is largely due to rapid social change.

Javanese Family and Child-Rearing

The Javanese word for “household” is somah. The nuclear family (kuluwarga or somah) forms the core of Javanese society and typically consists of a married couple and their unmarried children, though it may also include other relatives and, at times, married children and their families. Kin obligations are recognized equally on the mother’s and father’s sides. Descendants of a shared great-grandparent belong to a golongan or sanak-sadulur, a kin group whose members assist one another in hosting major celebrations and come together on Islamic holidays. A broader kin group, the alur waris, is oriented toward the care of an ancestral grave dating back seven generations; a descendant living near the grave coordinates the participation of relatives who are scattered elsewhere. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Most peasants and average urban prijaji live in monogamous nuclear-family households of about five or six people. In contrast, high-ranking prijaji and nobles tend to have larger, polygynous, uterolocal extended families. Inheritance practices reflect these family arrangements: houses and their surrounding garden plots usually pass to a married daughter or granddaughter after a period of shared residence, while fruit trees, livestock, and farmland are divided equally among all children. Family heirlooms, however, are most often inherited by a son.

Young children are indulged until roughly two to four years of age, after which discipline and moral instruction begin. Common disciplinary methods include stern verbal reprimands, corporal punishment, comparisons with siblings or peers, and warnings of social disapproval or outside sanctions. These practices encourage children to be cautious and reserved, especially around strangers. Mothers play the central role in socialization and remain the main sources of affection and emotional support, while fathers are more emotionally distant. Older siblings frequently help care for younger children. Girls’ first menstruation is marked quietly with a slametan, or communal meal, whereas boys’ circumcision, usually between ages six and twelve, is a major and highly significant rite.

Parents are expected to advise and correct their children throughout their lives, regardless of the child’s age. Children, by contrast, are not supposed to criticize or correct their parents except in the most indirect ways. Although fathers are formally regarded as heads of the household, mothers often exercise greater day-to-day authority, as women are permitted to be more direct. Men are expected to maintain emotional restraint, since visible emotion could undermine the dignity that underpins their authority. Reflecting these values, about two-thirds of Javanese reportedly use kromo, the language of respect, when greeting their parents or asking for help, and roughly half continue to use kromo even in relaxed conversation with them.

Javanese Marriage

Arranged marriages negotiated by parents and family elders still occur in some villages, but most people today choose their own spouses. Certain unions are considered taboo, notably marriages between first cousins—especially the children of two brothers—and marriages in which the man belongs to a younger generation than the woman. Other types of marriage are socially disapproved of, though their associated supernatural dangers can be averted through appropriate protective rituals. The concept of preferred marriage partners is not widely recognized. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Most marriages are monogamous. Polygyny is uncommon and is largely confined to segments of the urban lower class, orthodox high-ranking prijaji, and the nobility. There is no strict rule governing postmarital residence, although neolocal residence (with the husband’s family or community) is considered ideal.Uxorilocal residence (with the wife’s family or community) is widespread in southern Central Java, while high-ranking prijaji and nobles often reside in the home of either set of parents. Urban prijaji are more likely to establish independent households. Divorce is relatively common and is carried out according to Islamic law.

Ideally, a married couple sets up a separate household if economic circumstances permit; if not, they usually live with the wife’s parents. Polygyny is rare in practice—historically, only kings and certain aristocrats maintained harems. Divorce rates are particularly high among villagers and poorer urban residents. After divorce, children generally remain with the mother, but if she remarries they may live with other relatives. Inheritance can be divided through perdamaian, a process of family deliberation aimed at ensuring support for those most in need. A child who remains in the parental home to care for aging parents may also receive the largest share of the family property.

Javanese Wedding

The marriage and wedding process begins when a man makes a formal inquiry to the woman’s father or wali—a paternal relative who may act in place of a deceased father—to determine whether she is already promised to someone else. If the response is favorable, the process continues with the presentation of gifts from the man’s family to the woman’s side. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Marriage formalities include a gift from the groom’s relatives to the bride’s parents, a gathering of the bride’s kin at her home on the eve of the wedding, civil and religious transactions, and a ceremonial meeting of the couple. The night before the wedding, known as midadareni—when heavenly nymphs are believed to descend to bless the union—the bride’s family visits ancestral graves to seek their blessing. That evening, relatives, neighbors, and friends gather for a slametan feast, while close kin remain awake throughout the night preparing palm-leaf decorations (janur). A dukun manten is responsible for dressing and adorning the bride for the ceremony.

The wedding ceremony itself marks the completion of the Islamic marriage contract between the groom and the bride’s father or wali. The groom arrives at the bride’s house with his entourage, meets the bride, and takes his place beside her on the bridal dais. The groom’s parents then enter to the accompaniment of the gamelan piece Kebo Giro, today often played from a recording. The couple performs sungkem, bowing to their parents and senior relatives as a sign of respect. Guests are then served food and entertained by dances performed by young female relatives of the couple. The groom may take the bride to his home only after five days, after which the couple visits his relatives and neighbors for a simpler reception known as ngunduh temanten. Although wedding ceremonies were simplified after Indonesian independence, the trend reversed during the New Order period, when affluent families revived elaborate traditional rituals and ornate costumes to display social status.

Gender Issues Among Javanese

Javanese ideas about gender difference are nuanced and sometimes paradoxical. Men—especially priyayi elites—are often viewed as more capable of the emotional restraint and refined self-control prized in Javanese culture, including mastery of subtle linguistic etiquette. This self-discipline is believed to confer spiritual potency, enabling men to elicit respect and compliance without overt force. At the same time, men are also thought to be less able than women to restrain their desires, particularly for sex and money. As a result, women are often seen as more effective traders and financial managers, and it is common for husbands to hand over most or all of their earnings to their wives, who manage household finances. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Javanese women draw on two contrasting yet equally respected behavioral models. One emphasizes modesty and restraint, exemplified by Sumbadra, a wife of the wayang hero Arjuna. The other highlights assertiveness and courage, embodied by Srikandi, another of Arjuna’s wives. Gender differences are often expressed through the contrast between women as kasar (coarse) and men as halus (refined). Yet the male ideal—again represented by figures such as Arjuna—shares the same grace and gentleness associated with the female ideal. In both cases, refinement is understood as the product of inner discipline rather than passivity.

Central Java’s Gender-Related Development Index (which combines women’s health, education, and income relative to men’s) stands at 58.7, while East Java records 56.3 and Banten 54.9—all below Indonesia’s national GDI of 59.2. Yogyakarta is an exception, with a markedly higher score of 65.2, only slightly below Jakarta’s. Gender Empowerment Measures, which gauge women’s participation and influence in political and economic life, show similar patterns: 51.0 for Central Java, 54.9 for East Java, 48.6 for Banten, and 56.1 for Yogyakarta, compared with a national GEM of 54.6.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025