JAVANESE AND JAVA

The Javanese are Indonesia’s and Southeast Asia's largest ethnic group and the third largest Muslim ethnic group in the world following Arabs and Bengalis. They live primarily in the provinces of east and Central Java but are found throughout Indonesia’s islands. “Wong Djawa” and “Tijang Djawi” are the names that Javanese use to refer to themselves. The Indonesian term for them is “Ornag Djawa.” The word Java is derived from the Sanskrit word “yava”, meaning “barely, grain.” The name is very old and appeared in Ptolemy’s “Geography”, from Roman Empire of the A.D. 2nd century. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

The majority of Javanese llive in Jawa Timur and Jawa Tengah provinces; most of the rest live in Jawa Barat Province and on Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and other islands. Altogether, some 150 million people live on Java, about half the population of Indonesia. Although many Javanese express pride at the grand achievements of the illustrious courts of Surakarta and Yogyakarta and admire the traditional arts associated with them, most Javanese tend to identify not with that elite tradition, or even with a lineage or clan, but with their own village of residence or origin. These villages, or desa, are typically situated on the edge of rice fields, surrounding a mosque, or strung along a road.

Java is the world's most populous island and the center of Indonesia culture, politics and economic life. Historical events that took place here shaped Indonesia as a whole. Outsiders still seek it out as the place to make one’s name and seek fame and fortune in the archipelago. It is an incredibly rich place, with a rich cultural traditions and places of extraordinary beauty that are not marred by island’s dense masses, noise and traffic. It is about a third the size of California but has more than three times the people.

Long and narrow and about the size of Alabama or Britain, Java covers 132,107 square kilometers (50,229 square miles) and extends about 1,100 kilometers (700 miles) from east to west and 30 to 200 kilometers (20 to 130 miles) from north to south. It is located between 6̊and 9̊south of the Equator, divided in East Java, Central Java and West Java and encompasses thin, fertile, densely populated coast plains and mountains and volcanos. They are a few remaining tracts of rain forest left but most of the land is cultivated, primarily for rice.. The climate is tropical. The wet season lasts from September to March and the dry season is from March to September. The mountains and plateaus are somewhat cooler than the lowlands.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVANESE RELIGION: ISLAM, MYSTICISM, FESTIVALS, BELIEFS, PRACTICES factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE CULTURE: MUSIC, SHADOW PUPPETRY, FOLKLORE, LITERATURE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, GENDER, CUSTOMS, CLASSES factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE LIFE: VILLAGES, HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL JAVA factsanddetails.com

EAST JAVA factsanddetails.com

Javanese Population

There are over 100 million Javanese, Javanese people make up 40 percent to 45 percent of the total population of Indonesia, with figures around 40.2 percent to 42.65 percent being the most commonly cited in recent data. The Sundanese are the next largest group, making up about 15 percent of Indonesia’s population. The Javanese population was approximately 2 million in 1775. In 1900, the population of the island of Java was around 29 million, In 1990, the population of Java and the small island of Madura was estimated to exceed 109 million. At that time, Jakarta, the capital city, had a population of about 9.5 million. The combination of population growth and small, fragmented landholdings has produced severe overcrowding and poverty. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993, Google AI]

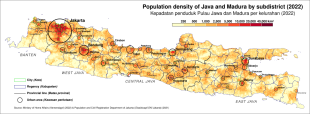

According to the 2000 census, Javanese made up 41.7 percent of Indonesia’s population—about 83.9 million people—making them larger than any other national population in Southeast Asia or Europe. Closely related groups speaking Javanese dialects but counted separately included the Bantenese (4.1 million) and Cirebonese (1.9 million) in western Java. Java is also one of the most densely populated regions in the world. Rural population density ranges from about 850 people per square kilometer to as high as 2,000 around Yogyakarta. By 2005, Central Java averaged 982 people per square kilometer and East Java 757—far higher than West Sumatra (106) or Central Kalimantan (12). Urban crowding is especially intense because most housing is low-rise rather than high-rise. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The Javanese heartland includes Central Java, East Java (excluding Madura), and the Special Region of Yogyakarta. For centuries, Javanese have also lived along the north coast of West Java, particularly in Cirebon and Banten. Within Javanese society, several regional subcultures are recognized. The main divide is between the coastal pesisir and the inland kejawen. The pesisir—stretching along the north coast and centered on places like Cirebon, Demak-Kudus, and Surabaya—has strong ties to trade and to Islamo-Malay culture. The kejawen of the interior, centered on the old royal cities of Surakarta (Solo) and Yogyakarta, emphasizes a syncretic blend of Islam with older Hindu-Buddhist traditions. Much of East Java today is ethnically mixed, reflecting past wars and migrations, and includes Madurese, migrants from Central Java, Hindu-Buddhist Tenggerese, and the Balinese-influenced Osing people.

Migration has long been a feature of Javanese history. As early as the 15th century, Javanese merchants, artisans, and servants were prominent in Malacca. From the 19th century onward, population pressure and land scarcity pushed large numbers of Javanese to migrate as laborers and later as transmigrants to Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi. Today, Javanese make up about 62 percent of Lampung’s population, 32 percent of North Sumatra’s, 30 percent of East Kalimantan’s, and 12 percent of Papua’s. More than one in three residents of Jakarta is Javanese. These movements helped reduce the share of Indonesians living on Java and Madura from 68.5 percent in 1960 to 58.7 percent in 2005.

Under colonial rule, Javanese laborers were also sent abroad to places such as Malaya, South Africa, New Caledonia, Curaçao, and Suriname, where people of Javanese descent still make up about 15 percent of the population. In some of these communities, Javanese language and cultural traditions have survived for more than a century.

Javanese Dominance in Indonesia

The Javanese dominate many facades of Indonesian life. They control the government and the military and also control large sectors of the economy. Many of Indonesia's most lucrative export crops are grown on Java. Non-Javanese Indonesians have often complained that Dutch colonial rule was replaced by a kind of Javanese “colonialism.” From the perspective of Jakarta’s multiethnic, development-oriented elite, however, Javanese culture is seen as just one regional culture among many—albeit one with far greater influence over national life. Javanese culture itself is not monolithic. It is shaped by the same tensions that run through Indonesian society as a whole. Javanese Muslim purists, for example, often feel closer to Malays, Minangkabau, or Bugis Muslims than to fellow Javanese whose secular or syncretic outlooks align more with Balinese, Dayak, or Torajan traditions. [Source: Canadian Centre for Intercultural Learning, intercultures.gc.ca; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Because Javanese make up Indonesia’s largest ethnic group, their language and customs are highly visible in everyday life, especially in the workplace. Javanese is frequently spoken among colleagues, and Javanese norms of politeness and social harmony often set the tone. Communication tends to be indirect and high-context, with an emphasis on courtesy and avoiding confrontation. As a result, Javanese employees may be reluctant to voice problems openly or deliver bad news, making close and supportive supervision important, particularly for outsiders unfamiliar with these norms.

Historical and economic factors have reinforced perceptions of Javanese dominance. During the years of Suharto’s rule, the government’s transmigration program moved large numbers of people—many of them Javanese—to outer islands, officially to reduce population pressure but widely seen as contributing to ethnic tension. At the same time, uneven development has driven internal migration toward economic centers such as Jakarta and Bali. In places like Bali, the large presence of Javanese workers has sometimes fueled resentment and stereotypes, with Javanese often unfairly blamed for social problems.

Early History of Java

The Austronesian ancestors of the Javanese likely arrived on Java around 3000 BC, possibly from the coast of Kalimantan. The name “Java” may originally have meant an “outlying island” from the perspective of Borneo or Sulawesi. By about 2,000 years ago, the Javanese had mastered metalworking and formed complex political communities beyond the village level. They later adopted—and reshaped—elements of Indian religion, art, and statecraft. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

By the early medieval period, “Java” was a broad term used by outsiders for much of the island world between China and India. In the Islamic world, Muslims from Southeast Asia were known as jawi. Wet-rice agriculture and organized states already existed in Java before the eighth century. From the seventh century onward, inscriptions and Chinese records describe kingdoms in central Java, followed by the rise of small Hindu-Buddhist states between the eighth and fourteenth centuries.

In the tenth century, the center of Hindu-Javanese culture shifted eastward to the Brantas Valley. This move was likely driven by environmental disruption in central Java—possibly volcanic eruptions—as well as by better access to maritime trade routes.

Great Kingdoms of Java

Mataram, arose as Srivijaya began to flourish in the early eighth century, in south-central Java on the Kedu Plain and southern slopes of Mount Merapi (Gunung Merapi). Mataram’s early formation is obscure and complicated by the rivalry of two interrelated lines of aspiring paramount rulers, one supporting Shivaist Hinduism (the Sanjaya) and the other supporting Mahayana Buddhism (the Sailendra, who had commercial and family connections with Srivijaya).

Despite the importance of trade, Java’s first great kingdom, Mataram, arose in the fertile interior of central Java. Its wealth supported the construction of monumental temples such as Borobudur and Prambanan, whose scale rivaled anything in India. At its height, Javanese cultural influence reached as far as mainland Southeast Asia; a Khmer prince who later founded the Angkorian Empire had once lived in Java.

One of Java’s most famous empires, Majapahit, emerged near present-day Surabaya in the late 13th century and flourished in the 14th and 15th centuries. During this period, international trade was dominated by Indian Muslims and Chinese merchants. As political power shifted toward coastal port towns in the 16th century, Indian and Malay Muslims became increasingly influential, and Islam spread among the Javanese elite in forms shaped by earlier Indian traditions. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The Mataram Kingdom rose again in the 16th century and lasted until the mid-18th century, during a time when Europeans—first the Portuguese, then the Dutch—came to dominate regional trade. Around 1750, the Dutch East India Company broke Mataram into smaller vassal states, which later fell under direct Dutch colonial rule.

Although Majapahit’s power was likely less extensive than later legends claimed, it stood at the center of a wide trading network across the archipelago. That same network would later be taken over by the Dutch East India Company, laying foundations for the colonial state that eventually became modern Indonesia.

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

MATARAM KINGDOM: HISTORY, HINDUISM, PRAMBANAN, AFTERWARDS factsanddetails.com

SAILENDRA DYNASTY: BUDDHISM, BOROBUDUR, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

SINGHASARI, KEDIRI, MARCO POLO AND THE MONGOL INVASION OF JAVA factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

Java Under Europeans and the Dutch

In the 15th century, ports along Java’s north coast came under the influence of Muslim Malacca, then the main hub of international trade. These ports were increasingly ruled by the descendants of non-Javanese Muslim merchants. New Islamic states, led by Demak, defeated the weakening Majapahit kingdom and spread Islam inland. By the 16th century, a new Mataram state emerged in central Java, blending Islam with older Hindu-Buddhist traditions. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Mataram reached its height under Sultan Agung, who came close to unifying all of Java. His efforts were blocked by the growing power of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), which had established itself along the coast. After Agung’s death in 1646, Mataram fell into prolonged civil wars and foreign вмеш interference. The VOC steadily expanded its influence, seizing control of the north coast and eventually forcing the permanent division of the kingdom in 1755 into two weakened courts at Surakarta (Solo) and Yogyakarta.

Apart from a brief period of British rule, Java remained under Dutch control. After the VOC went bankrupt in 1799, the Dutch state gradually assumed direct authority, completing its control in the 1830s after crushing a major rebellion led by the Yogyakarta prince Diponegoro. Dutch pacification stripped Javanese rulers of real political power, leaving court culture, ritual, and the arts as their main sources of authority.

Under the Cultivation System, the colonial state—working through local aristocrats and Chinese intermediaries—forced peasants to pay taxes by growing export crops such as sugar on part of their rice land. Combined with rapid population growth, this system impoverished much of the rural population.

Resistance took many forms. Elites withdrew into refined court culture, contrasting Javanese civility with what they saw as Dutch harshness. Peasants joined movements like the Samin, practicing nonviolent refusal to pay taxes. Over time, new technologies—steamships, railways, telegraphs, and newspapers—along with the spread of European racial ideas, expanded political awareness beyond Java itself.

By the early 20th century, nationalism and communism had taken root. After Japanese occupation during World War II, Indonesia declared independence in 1945. Following four years of fighting, the Dutch formally transferred sovereignty to Indonesia in 1949, ending centuries of colonial rule on Java.

Java and Indonesian Nationalism, Islam and Independence

Javanese activists played a leading role in the Islamic, communist, and nationalist movements that challenged Dutch colonial rule in the early 20th century. Surakarta was the birthplace of Sarekat Islam in 1911, the first mass political organization in the Dutch East Indies. Surabaya later became a center of radical politics, witnessing a communist uprising among soldiers and sailors in 1917 and fierce resistance in 1945 against British troops sent to restore Dutch rule after the Japanese occupation. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

After independence, Yogyakarta was granted special provincial status in recognition of its sultan’s strong support for the independence struggle. Javanese dominance also extended into national leadership: all but one of Indonesia’s presidents have been Javanese, the exception being B. J. Habibie, who was Bugis. Sukarno was partly an exception, as he was half Balinese.

Java, together with Bali, suffered most of the violence during the anti-communist massacres of 1965–1966. A key cause was land conflict in rural Java between landowning peasants aligned with Islamic parties and landless peasants linked to the Communist Party. Under Suharto’s New Order regime, state-led development emphasized export-oriented industries in Java’s cities. This further increased Java’s economic importance, even though Indonesia’s economy had long relied on oil and other natural resources from the outer islands.

Although Java has experienced frequent low-level violence—such as vigilante attacks, accusations of black magic, and church burnings—it has generally avoided the large-scale ethnic and religious conflicts seen elsewhere, notably in the Maluku Islands and Kalimantan. One major exception was Surakarta, which saw severe anti-Chinese riots in May 1998.

Languages Spoken on Java

Five major languages are spoken in Java: 1 Javanese around Jakarta; 2) Bahasa Indonesian in northwest and central Java; 3) Sundanese in southwest Java; 4) Madurese in northeast Java and nearby Madua island; and 5) Balinese in eastern Java and Bali.

Most Javanese are at least bilingual. They speak Bahasa Indonesia, the Indonesian national language, in public and in dealings with other ethnic groups, but at home and among themselves they speak Javanese.

Sundanese, Madurese and Javanese are similar Austronesian language related to Malay. The Javanese language is divided into several regional dialects. The people of Solo and Yogya regard their own speech as the most refined and view other dialects as corruptions (other Javanese often agree). ^

The earliest known Javanese writing dates to the fourth century CE, when Javanese was written using the Pallava alphabet. By the 10th century, the Kawi alphabet had developed from the Pallava alphabet and taken on a distinct Javanese form. From the 15th century onward, Javanese was also written with a version of the Arabic alphabet called Pegon. By the 17th century, the Javanese alphabet had evolved into its current form. During the Japanese occupation of Indonesia from 1942 to 1945, the use of the Javanese alphabet was prohibited. Since the Dutch introduced the Latin alphabet to Indonesia in the 19th century, it has gradually supplanted the Javanese alphabet. Today, it is used almost exclusively by scholars and for decoration. Those who can read and write it are held in high esteem. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Javanese Language

Like many cultural groups in Indonesia, the Javanese have their own language. Javanese is an Austronesian language spoken by roughly 100 million people, mainly in Indonesia and also among Javanese communities in Suriname. It belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family and has a written tradition dating back to the 8th century. Classical Javanese literature flourished for centuries, and the language developed multiple speech styles shaped by strict rules of etiquette, though in modern usage these levels are gradually being simplified. [Source: omniglot; hello-indonesia.com]

Today, Javanese is spoken primarily in central and eastern Java, along the north coast of West Java, and in parts of Madura, Bali, Lombok, and western Java. It was once the court language of Palembang in South Sumatra until the late 18th century and has served as a literary language for over a thousand years. Although Javanese has no national official status, it is recognized as a regional language in Central Java, the Special Region of Yogyakarta, and East Java. It is taught in some schools and used in local radio, television, and print media. The traditional Javanese script, once also used for Balinese and Sundanese, has largely been replaced by the Latin alphabet.

Compared with Bahasa Indonesia, Javanese is linguistically and socially complex. It traditionally includes multiple speech levels—often described as ranging from informal to highly refined—that reflect differences in age, social status, and familiarity between speakers. Regional variation is also important: East Javanese speech is often perceived as more direct or rough, while Central Javanese places greater emphasis on politeness and refined manners. Loud emotional expression is generally discouraged, and indirect communication is preferred. These patterns reflect long-standing courtly traditions shaped by Hindu-Buddhist influences that predate the spread of Islam in Java.

Characterics of the Javanese Language

In a way comparable among major languages only to Japanese and Korean, Javanese speech constantly signals social hierarchy. Every conversation requires speakers to choose an appropriate speech level based on age, status, and social distance, with the expectation that the same respect will be returned. Despite many subtle gradations, Javanese is often described as having two main levels: ngoko and kromo. Ngoko is the everyday language of thought and intimacy, used with close friends, equals, or social inferiors. Kromo is reserved for elders, superiors, or people whose status is uncertain. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Most vocabulary remains the same across levels, but the words that change are among the most common, so even simple sentences can sound completely different. For example, “Where are you coming from?” is Soko ngendi? in ngoko and Saking pundi? in kromo. “I can’t do it” becomes either Aku ora iso or Kulo mboten saged. The feel of the two levels also differs: ngoko can sound blunt or even harsh and is often very precise, while kromo is spoken softly and slowly and is intentionally vague.

Fluency in kromo is learned rather than automatic. In the past, peasants who lacked kromo often remained silent before aristocrats or relied on intermediaries. Today, most Javanese avoid causing offense by switching to Indonesian when unsure—using it as a kind of neutral or modern substitute for kromo.

Javanese Names and Swear Words

Naming practices also reflect Java’s layered cultural history. Islamic-Arabic names are common—such as Abdurrahman Wahid—but Sanskrit-derived names are equally typical. Javanese generally do not use surnames; figures like Sukarno and Suharto were known by a single name. Many Muslims combine Arabic and Sanskrit elements, while Christians often pair Latin names with Sanskrit ones, reflecting the deep cultural layering that characterizes Javanese society. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Javanese Insults and Swearing — English Translation; Itil — Pussy; Itil'e mbokmu — Your mother's pussy; Koplak — Stupid; Koplo — Stupid; Utekmu — Your stupid brain; Raimu — Your ugly face; Cangkemmu — Your rotten mouth; Congormu — Your rotten lips; Asu — Stupid dog; Kampret — Sucking bat (sucker); Cocot — Your mouth; Tlembokne — Your mother is shit; Kakekane — Your damn grandpa; Kirik — Stupid puppy; Pekok — Moron; Ntolmu — Your dick; Metemu — Your balls; Saksir to sir — Mind your own business; Bebas to bas — Mind your own business; Ndogmu — Your balls; Lonte — Bitch/Whore; Celeng — Boar [Source: myinsults.com]

Lambemu — Your rotten lips; Matamu — Your rotten eyes; Ndasmu — Your rotten head; Bocah ra aturan! — You have no manners!; Janjuk — Fuck; Bocah asu ra tau diaturi karo mbok mu to? — You useless son of a dog, does your mother never teach you any manners?; Opo ndelok-ndelok matane! — What the fuck are you looking at?; Rai kontol — Dick face; Lambemu turah to? — You swear too much! (lit. your mouth is too long); Wong pekok — Stupid person; Gejhus — Anal hair; Gemblung — Crazy; Pejuh — Sperm; Silit — Damn (lit. asshole); Kitul — Fucking (lit. having sex); Jancuk — Fuck; Kontol — Penis; Ndhasmu sempal — (I hope) your forehead cracks open; Utekke njeblug — (I hope) your brain explodes; Utek(mu) buntel kopet — (your) brain is a shit bag; Kenthong — Sexual intercourse

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025