JAVANESE RELIGION

Nearly all Javanese identify as Muslims, but only a portion strictly follow the Five Pillars of Islam and the practices associated with orthodox Middle Eastern Islam. Those who do are known as santri and are often divided into two broad groups. “Conservative” santri maintain long-established Javanese forms of orthodox Islam, while “modernist” santri reject many local traditions and embrace a more scriptural Islam shaped by Western-style education. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

For many Javanese, religion is highly syncretic. Islam is layered onto older Hindu-Buddhist and indigenous spiritual traditions. This produces a deep cultural divide between the santri, who adhere closely to Islamic doctrine, and the abangan, who practice a more relaxed, ritual-based faith. This distinction has long carried social, class, and political significance in Javanese society.

About 12 percent of Java’s population—including Chinese Indonesians and migrants from other islands—follows religions other than Islam. Christianity is the largest minority faith, with Roman Catholics especially prominent. Catholic worship in Java has incorporated local culture, using gamelan music in the Mass and wayang shadow puppetry to teach biblical stories. Traditional Javanese gestures of respect, such as pressing the palms together at the forehead, are also used during key moments of the service.

A strong sense of fatalism runs through Javanese thought. Values such as acceptance (nerimo), patience (sabar), and emotional self-control (ikhlas) are seen as essential to achieving inner calm. Life on earth is often described as brief and transitory, like “stopping for a drink” (mampir ngombe). Mystical practices, including meditation and spiritual retreats, are common ways to gain inner power and have long attracted the Javanese aristocracy. Many mystical movements, known collectively as kebatinan (“inner spirituality”), deliberately distance themselves from formal Islam. Although they have large followings, they have repeatedly failed to gain official recognition from the state.

On the slopes of Mount Bromo in East Java lives the Tenggerese, an ancient Javanese subgroup. They practice a folk religion rooted in Majapahit-era Hinduism and centered on honoring Joko Seger, the guardian spirit of Bromo.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVANESE PEOPLE: HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE CULTURE: MUSIC, SHADOW PUPPETRY, FOLKLORE, LITERATURE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, GENDER, CUSTOMS, CLASSES factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE LIFE: VILLAGES, HOUSES, FOOD, CLOTHES, WORK factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL JAVA factsanddetails.com

EAST JAVA factsanddetails.com

Javanese Muslims

In Indonesia, santri refers specifically to Muslims who receive formal Islamic education in pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) or study closely with religious teachers. More broadly, the term describes Muslims who strictly observe Islamic teachings. Santri are found across all social classes but are especially prominent in commercial and trading communities. They carefully follow Islamic obligations: praying five times a day, attending Friday prayers at the mosque, fasting during Ramadan (puasa), avoiding pork, and striving to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Within this “purist” stream of Islam, santri are commonly divided into two groups. Conservatives maintain forms of orthodox Islam that have been practiced in Java for centuries, while modernists reject many local traditions and emphasize a more scriptural interpretation of Islam, often supported by Western-style education. These two tendencies are institutionally represented by powerful mass organizations: Nahdlatul Ulama for the conservative tradition and Muhammadiyah for the modernist one. Both once functioned directly as political parties and remain highly influential in religious and social life.

By contrast, non-santri Javanese Muslims are commonly known as abangan or Islam kejawen. While they revere God (Gusti Allah) and the Prophet Muhammad (Kangjeng Nabi), they generally do not perform the five daily prayers, fast during Ramadan, or seek to undertake the pilgrimage to Mecca. Their religious life centers not on mosque worship but on slametan—communal ritual meals held to mark life-cycle events, village purification rites, harvest festivals, Islamic holidays, and special occasions such as moving into a new house or performing ruwatan rituals to protect a child from misfortune.

Islamic religious life in Java includes several types of practitioners. Some groups are organized into sects structured around hierarchical teacher–disciple relationships, linking a guru or kiai (religious teacher) with murid (students). Individual kiai attract followers to their pondok or pesantren—boarding schools resembling monasteries—where they teach Islamic doctrine and law. Alongside orthodox Islam, practices of magic and sorcery are widespread. Numerous kinds of dukun operate in Javanese society, each specializing in particular rituals, such as those connected with agriculture or fertility, as well as divination and healing.

Mystical Javanese Islam

Peasant abangan generally understand the basic framework of Islam but do not observe it strictly. Their religious outlook is syncretic, combining indigenous beliefs with elements of Hindu-Buddhism and Islam. Alongside belief in Allah, abangan acknowledge Hindu deities and a wide array of spirits thought to inhabit the natural environment. They also believe in a form of mystical power possessed by dukun—specialists who may serve as healers, ritual experts, or sorcerers. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Offerings such as flowers, incense, coins, and rice cakes are commonly placed on bamboo trays or banana leaves for spirits at crossroads, beneath bridges, at large trees, and other spiritually charged locations. Abangan respect the spiritual potency (kesakten) believed to reside in heirloom objects such as gongs, kris daggers, and royal carriages. They also believe that paying homage at the tombs of rulers and other exceptional figures from the past can bring spiritual or material benefits. Many of these practices are not exclusive to abangan: conservative santri, for example, regularly make pilgrimages to the graves of Islamic saints, a practice criticized by modernists as idolatrous. Both abangan and santri commonly consult dukun of various kinds, including spirit mediums, masseurs, acupuncturists, herbalists, midwives, sorcerers, and numerologists.

The religious practices of priyayi abangan resemble those of peasant abangan but are generally more refined and philosophical. They emphasize an elaborate worldview centered on fate and mysticism. Asceticism and meditation are central practices, and religious life often takes shape within sects led by spiritual teachers (guru).

Javanese Spiritual Beings

Javanese belief recognizes a rich hierarchy of supernatural beings. Memedis are frightening spirits, including figures such as sundal bolong and the mischievous gendruwo. Gendruwo are said to appear as familiar relatives in order to abduct people and render them invisible; anyone who accepts food from a gendruwo is believed to remain invisible forever. Lelembut are spirits that possess humans, while tuyul are spirit familiars that can be acquired through fasting and meditation. Demit inhabit eerie or dangerous places, and danyang serve as guardian spirits of villages, palaces, and sacred sites. Above all stands Ratu Kidul, the Queen of the South Sea, believed to be the mystical consort of Java’s rulers. Her favored color is green, and young men are warned not to wear green along the southern Indian Ocean coast, lest they be drawn into her underwater realm. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Another revered group in Javanese tradition is the wali songo, the Nine Saints credited with bringing Islam to Java. Of diverse origins—Arab, Egyptian, Persian, Central Asian, and Chinese—they are remembered not only for their piety but also for their legendary powers, such as flying. They are also said to have spread Islam through Javanese cultural forms. Sunan Bonang, for example, used Javanese sung poetry and gamelan music to convey Islamic teachings. Their tombs along Java’s north coast remain major pilgrimage destinations, especially those of Sunan Giri in Gresik near Surabaya, Sunan Kudus in Kudus, and Sunan Gunung Jati in Cirebon. Another figure who attracts pilgrims is Zheng He, known locally as Sam Po Kong; both Muslim Javanese and non-Muslim Chinese visit his shrine and temple in Semarang.

Javanese Religious Ceremonies and Festivals

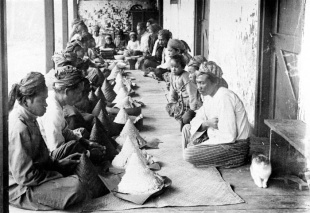

The slametan, a communal ritual meal, is central to abangan religious life and is sometimes also practiced by santri. Its aim is to create slamet—a state of calm, harmony, and spiritual balance. Held in a private home and typically attended by close neighbors, a slametan marks major life-cycle events, certain dates in the Muslim calendar, and occasions meant to safeguard the well-being of the wider community. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Javanese concepts of time blend the seven-day Islamic–Western week (Sabtu, Minggu, Senin, Selasa, Rebo, Kemis, Jum’at) with an indigenous five-day cycle (Legi, Paing, Pon, Wage, Kliwon). Each day is defined by its place in both systems—for example, Selasa Pon or Rebo Legi—a combination that recurs every 35 days. Important events such as birthdays, rituals, and performances are often scheduled according to these recurring pairings.

The first day of the Islamic year, beginning at sunset on 1 Sura, is considered especially rich in mystical significance. On this night, many people remain awake to watch processions like the kirab pusaka, in which royal heirlooms are paraded in Solo, or to meditate on mountains or along the coast. Standing all night in cold running water is believed by some to build spiritual power. The Prophet Muhammad’s birthday, observed on 12 Mulud, is celebrated in Yogyakarta and Solo with the week-long Sekaten fair. Ancient gamelan ensembles, played only for this occasion, accompany processions on the festival day featuring conical “mountains” of glutinous rice symbolizing male, female, and child.

Javanese Funerals and Beliefs About Death

Funerals in Java usually take place within hours of a death and are attended by neighbors and close relatives who can arrive in time. A coffin is quickly constructed and a grave prepared, while a village official conducts the necessary rituals. A brief ceremony is held at the deceased’s home, followed by a procession to the cemetery for burial. Afterward, a slametan is held, with food typically supplied by neighbors. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

As in other areas of social life, Javanese funerals are characterized by emotional restraint. Graves are visited and cared for regularly, especially at the beginning and end of the fasting month. The Javanese believe that bonds with the dead continue, particularly the ties between parents and children. Families observe a series of slametan rituals at set intervals after a death, culminating in a final ceremony 1,000 days later. Beliefs about the afterlife vary: some follow orthodox Islamic ideas of judgment and eternal reward or punishment, while others believe that spirits or ghosts continue to influence the living, or even in reincarnation—a view strongly rejected by orthodox Muslims.

Ritual observances surround death. Javanese families hold slametan ceremonies for the deceased on the third, seventh, fortieth, hundredth, and thousandth days after death. On Selasa Kliwon and Jum’at Kliwon, offerings—typically flower petals placed in half-filled glasses of water—are made to the spirits of the dead. During Ramadan, families commonly visit graves to scatter flowers in remembrance of departed relatives.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025