JAVANESE LIFE, EDUCATION AND MEDICINE

With the disappearance of uncultivated land long ago, equal inheritance practices have left many Javanese peasants dependent on very small plots. A significant number have lost their land entirely and now rely on tenancy, sharecropping, or wage labor under wealthier peasants who can afford fertilizers and limited machinery. Traditional customs that once softened hardship—such as allowing the poorest villagers to glean leftover grain after harvest—are increasingly disappearing. During the New Order period (1966–1998), the government pressed ahead with dam construction and other development projects despite resistance from peasants facing displacement. At the same time, the military supported industrial interests by suppressing labor unrest in the rapidly expanding factories of Java’s densely populated cities. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Socioeconomic indicators reflect these pressures. In 2005, Central Java’s Human Development Index (HDI), which combines income, health, and education, stood at 69.8, slightly above the national average of 69.6. East Java’s HDI was lower at 68.5, as was Banten’s at 68.8. By contrast, the Special Region of Yogyakarta ranked among the highest in the country with an HDI of 73.5. Central Java’s GDP per capita, at US$6,293, was relatively low by Indonesian standards—below provinces such as West Sumatra and North Sulawesi, though higher than East Nusa Tenggara. East Java’s GDP per capita was considerably higher, at about US$11,090. Infant mortality rates (2000 figures) further highlight regional disparities: East Java recorded 47.7 deaths per 1,000 live births, nearly twice Jakarta’s rate; Central Java’s rate was slightly lower at 43.7, while Yogyakarta matched the national capital. All of these figures compare favorably with West Nusa Tenggara’s much higher rate of 88.6.

Literacy levels also lag behind national averages. In 2005, literacy stood at 87.4 percent in Central Java, 85.8 percent in East Java, and 86.7 percent in Yogyakarta—below the national rate of 90.4 percent reported in 2004, though comparable to other provinces with large poor populations, such as Bali and South Sulawesi.

Modern medical doctors are available and widely consulted in Java, particularly in urban areas, yet traditional healers and diviners remain important across Javanese society. Alongside dukun who perform magical rites are others who specialize in healing, including spell-casters, herbalists, midwives, and masseurs. Even urban prijaji who regularly seek biomedical treatment may also consult dukun for specific illnesses or psychosomatic complaints, reflecting the continued coexistence of scientific and traditional approaches to health.

RELATED ARTICLES:

JAVANESE PEOPLE: HISTORY, DEMOGRAPHICS, LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE RELIGION: ISLAM, MYSTICISM, FESTIVALS, BELIEFS, PRACTICES factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE CULTURE: MUSIC, SHADOW PUPPETRY, FOLKLORE, LITERATURE factsanddetails.com

JAVANESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, GENDER, CUSTOMS, CLASSES factsanddetails.com

CENTRAL JAVA factsanddetails.com

EAST JAVA factsanddetails.com

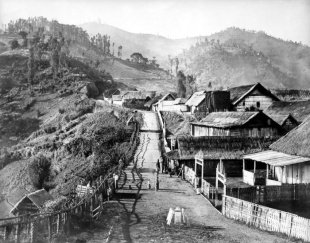

Javanese Villages, Towns and Houses

High population density gives Java an overall urban character, even in rural areas. Most people live in small villages and towns, while roughly a quarter reside in cities. Settlement is evenly spread across the island: villages are often only a few hundred meters apart and are rarely more than eight kilometers from the nearest town. Although Java contains many towns and cities, only Jakarta, Surabaya, and Semarang possess fully developed urban and industrial characteristics. Agricultural landholdings are typically small and highly fragmented. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Javanese villages (desa) take different forms depending on terrain. In the highlands they tend to cluster amid fields, while in the lowlands they often extend linearly along roads. Individual houses and yards are commonly enclosed by bamboo fences, and narrow paths—rarely wider than two meters—link the dukuh, or constituent hamlets. Each village has a balai desa (community meeting hall), several langgar (prayer halls) or a mosque, and a school. Gates marking neighborhood boundaries are widespread, as are open spaces used for weekly markets, bus stops, and parking areas for minibuses (bemo, kol, daihatsu) and pedicabs (becak).

The typical village house is small and rectangular, built directly on the ground. Traditionally it has earthen floors, a simple interior divided by movable bamboo partitions, and a thatched roof. Variations in house style are defined mainly by roof shape. Houses influenced by urban styles often feature brick walls and tiled roofs, while large open pavilions at the front are characteristic of the homes of high-ranking officials and members of the nobility.

Village houses generally use frames of bamboo, palm trunks, or teak, with walls of plaited bamboo (gedek), wooden planks, or brick, and roofs made of dried palm leaves (blarak) or tiles. Interior rooms are formed with movable gedek partitions. Traditional houses lack windows, relying on gaps in the walls or openings in the roof for light and ventilation. Roof design historically signaled social status: ordinary villagers lived under the serotong roof with two slopes; descendants of village founders used the limasan roof with double slopes on four sides; and aristocratic households were marked by the joglo roof, distinguished by three slopes on four sides and a prominent front pavilion (pendopo) for receiving guests and petitioners.

Javanese Food and Clothes

Meals center on rice and, in their simplest form, include stir-fried vegetables accompanied by dried salted fish, tahu (tofu), tempe (fermented whole soybeans), krupuk (fish or shrimp crackers), and sambel (chili sauce). Common everyday dishes include gado-gado, a salad of parboiled vegetables with peanut sauce; sayur lodeh, a vegetable stew cooked in coconut milk; pergedel, rich potato fritters; and soto, a soup made with chicken, noodles, and other ingredients. Well-known regional specialties include Yogyakarta’s gudeg, made from chicken and young jackfruit stewed in coconut milk; Solo’s nasi liwet, rice cooked in coconut milk; and nasi rawon, rice served with a dark, flavorful beef soup. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009; “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999]

Foods of Chinese origin are also widely popular, such as bakso (meatball soup), bakmi (fried noodles), and cap cay (stir-fried vegetables and meat). Snack foods often consist of crackers like emping, made from the mlinjo nut, and rempeyek, thin peanut crackers. Common sweets include gethuk, prepared from steamed and mashed cassava mixed with coconut milk and sugar, and a variety of glutinous rice desserts such as jenang, dodol, klepon, and wajik.

Many Javanese regularly buy prepared food from neighborhood peddlers and enjoy lesehan, late-night meals eaten while sitting on mats at sidewalk food stalls. For special occasions, a tumpeng slametan is served ceremonially. This cone-shaped mound of steamed rice is presented to guests, and the guest of honor uses a knife and spoon to cut off the tip of the cone—often decorated with a hard-boiled egg and chilies—and place it on a plate. A horizontal slice is then cut from the top and offered to the most respected guest, usually the eldest.

In everyday life, Javanese dress follows general Indonesian styles, with both men and women commonly wearing sarongs in public. Men’s ceremonial attire includes a sarong, a high-collared shirt, a jacket, and a blangkon, a folded headcloth shaped like a skullcap. Women wear a sarong with a kebaya, a fitted long-sleeved blouse, and a selendang draped over the shoulder. The traditional women’s hairstyle, known as sanggul, consists of long hair arranged in a thick, flat bun at the back of the head, now often created with a hairpiece. Handbags are routinely carried. In traditional dance costumes and wedding dress, men may leave the chest bare, while women’s shoulders are left uncovered.

Agriculture and Land on Java

About 60 percent of Javanese earn their livelihoods from agriculture. Wet-rice cultivation forms the core of the peasant economy, while fishing plays an important role in coastal villages. Animal husbandry remains limited because of land scarcity. Farmers also grow a variety of dry-season crops for sale. During the colonial period, the Dutch established plantations organized along Western business lines; this sector now survives as estate agriculture—highly capitalized, export-oriented, and separate from smallholder farming. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Peasant farmers typically cultivate both wet-rice fields and dry fields (tegalan), producing crops such as cassava, maize, yams, peanuts, and soybeans. In upland and mountain areas, many engage in market gardening, growing vegetables and fruits, including temperate-climate crops such as carrots.

Historically, much land was held communally, and villages supplied corvée labor for the king, local nobility, or colonial authorities. Communal land continues to exist today, reserved for public purposes such as schools, roads, cemeteries, and the support of the village head and his staff. Corvée labor was performed by groups of villagers known as kuli, who constituted the village’s main productive workforce. As compensation, communal land was granted to them for usufruct, and in some areas this status became hereditary along with the land itself. Many villages also maintain communal fields that are allocated to households on a rotating basis. Individual landholdings, however, remain small and highly fragmented.

Javanese Work and Economic Activity

Java has a dual economy that combines an industrial sector with a predominantly peasant-based rural economy. During the colonial period, the Dutch introduced enterprises organized along Western business lines. Today this sector encompasses estate agriculture, mining, and modern industry. It is highly capitalized and oriented mainly toward export production. Alongside it exist small-scale cottage industries and a dense network of local markets that support everyday economic life. [Source: M. Marlene Martin, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Rural Java is served by local markets, each typically catering to four or five villages. Retail trade in these markets is usually carried out by women. Small-scale industry remains limited, largely because of difficulties in access to capital, distribution, and marketing. In Central Java, cottage industries include silverwork, batik production, handweaving, and the manufacture of traditional cigarettes.

Most Javanese are farmers, local traders, or skilled artisans. Historically, intermediate trade and small industry were dominated by foreign Asians, while large plantations and major industries were controlled by Europeans. In precolonial times, society was divided primarily between royalty and nobility on one hand and the peasantry on the other. Under colonial rule and with the growth of administrative centers, two additional social groups emerged: landless laborers and government officials, known as prijaji. The prijaji are generally urban and internally stratified.

In rural areas, agriculture remains the dominant occupation. Some villagers engage in craft production or trade, but these activities are usually secondary to farming and pursued part-time. Most people devote the bulk of their labor to agricultural work. Learned professions—such as teachers, religious specialists, and puppeteers—are often filled by individuals from relatively affluent families. These roles carry considerable prestige but are also commonly practiced alongside farming. Local and central government officials occupy the highest positions in the local prestige hierarchy.

Traditionally, Javanese culture has valued white-collar employment and bureaucratic service over manual labor and commerce. In practice, however, many nonfarmers work as artisans or petty traders, with women forming the majority of small-scale vendors. On Java itself, larger businesses have often been owned by Chinese or, in some cases, Arab entrepreneurs, while in much of the rest of Indonesia Javanese have been prominent not only as civil servants and soldiers but also as merchants. Rapid economic growth in recent decades has drawn increasing numbers of Javanese—especially young women from rural areas—into factory and service-sector jobs. At the same time, landlessness and underemployment have pushed many into low-status occupations, including domestic service, street vending, fare collecting on minibuses (kenek), informal parking assistance, street music (ngamen), and other forms of marginal urban employment.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic, Live Science, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Encyclopedia.com, Times of London, Library of Congress, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Google AI, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various websites, books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025