MATARAM KINGDOM

The Mataram Kingdom—also known as the Medang Kingdom—was a Javanese Hindu–Buddhist state that flourished from the 8th to the 10th centuries. Centered first in Central Java along the Solo River and later shifting to East Java, it was founded by King Sanjaya and at various points came under the rule of the Buddhist Sailendra dynasty. Throughout most of its history, Mataram relied heavily on intensive rice agriculture and later gained additional wealth through maritime trade. Archaeological evidence and foreign accounts describe it as a populous, prosperous kingdom with a sophisticated and highly developed culture. [Source: Wikipedia, metapedia.org]

In the 8th century, the Hindu Mataram Kingdom and the Buddhist Sailendra Dynasty in the plains of Central Java emerged as powerful inland states. Unlike Srivijaya, whose wealth derived from maritime trade, these kingdoms were land-based and drew their strength from agricultural surpluses and the ability to organize large labor forces. Founded by King Sanjaya, Mataram’s rulers claimed a divine mandate, followed a form of Shaivite Hinduism, and built some of Indonesia’s earliest Hindu monuments on the Dieng Plateau. By the 9th century, however, political control in Central Java shifted to the Buddhist Sailendra dynasty.

Between the late 8th and mid-9th centuries, the Mataram kingdom experienced a remarkable flowering of classical Javanese art and architecture. This era saw the construction of numerous temples across the Kedu and Kewu plains, including some of Indonesia’s most iconic monuments: Kalasan, Sewu, Borobudur, and Prambanan. By around 850, Mataram had become the dominant political force in Java and later emerged as a significant rival to the powerful maritime empire of Srivijaya.

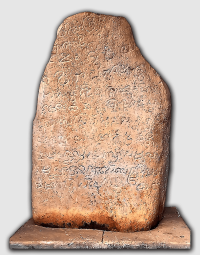

The earliest record of Mataram appears in the Canggal inscription of 732, discovered near Magelang. Written in Sanskrit and Pallava script, it describes the erection of a lingga (a symbol of Shiva) on a hill in Kunjarakunja, located on Yawadwipa (Java), a land said to be blessed with abundant rice and gold. The inscription recounts that Java had been ruled wisely by King Sanna, but fell into disorder after his death. His nephew, Sanjaya—son of Sannaha—seized the throne, restored unity, and brought peace and prosperity to the land.

According to to Lonely Planet: “At the end of the 10th century, the Mataram kingdom mysteriously declined. The centre of power shifted from Central to East Java and it was a period when Hinduism and Buddhism were syncretised and when Javanese culture began to come into its own. A series of kingdoms held sway until the 1294 rise of the Majapahit kingdom. [Source: Lonely Planet]

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

SAILENDRA DYNASTY: BUDDHISM, BOROBUDUR, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

SINGHASARI, KEDIRI, MARCO POLO AND THE MONGOL INVASION OF JAVA factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

Mataram, Sanjaya and Sailendra

Mataram, arose as Srivijaya began to flourish in the early eighth century, in south-central Java on the Kedu Plain and southern slopes of Mount Merapi (Gunung Merapi). Mataram’s early formation is obscure and complicated by the rivalry of two interrelated lines of aspiring paramount rulers, one supporting Shivaist Hinduism (the Sanjaya) and the other supporting Mahayana Buddhism (the Sailendra, who had commercial and family connections with Srivijaya). At some point between 824 and 856, these lines were joined by marriage, probably as part of a process by which the leaders of local communities (“rakai”or “rakryan”) were incorporated into larger hierarchies with rulers, palaces, and court structures. In this process, the construction of elaborately carved stone structures (“candi”) connecting local powers with Buddhist or Hindu worldviews played an important role. The best known and most impressive of these are the Borobudur, the largest Buddhist edifice in the ancient world (constructed between about 770 and 820 and located northwest of present-day Yogyakarta) and the magnificent complex of Hindu structures at Prambanan, located east of Yogyakarta and completed a quarter-century later. These and hundreds of other monuments built over a comparatively short stretch of time in the eighth and ninth centuries suggest that Javanese and Indic (Buddhist and Hindu) ideas about power and spirituality. [Source: Library of Congress*]

Scholars have generally identified a highly productive irrigated rice agriculture as the principal source of Mataram’s power, seeing it as a kind of inland, inward-looking antithesis to an outward-oriented, maritime Srivijaya, but such a distinction is overdrawn. Central Java was linked from a very early date to a larger world of commerce and culture, through connections with ports not far away on Java’s north coast. Like Srivijaya, Chinese, Indian, and other students of Buddhist and Hindu thought visited Mataram, and Javanese ships traded and made war against competitors in the archipelago (including Srivijaya) and as far away as present-day Cambodia, Vietnam, and probably the Philippines. Mataram was certainly not isolated from the wider world, and in some respects its commercial life may have been more sophisticated than that of its Sumatran contemporary, as it made common use of gold and silver monetary units by the mid-ninth century, some 200 years earlier than Srivijaya.

Politically, the two hegemonies were probably more alike than different. The rulers of both saw themselves and their courts (“kedatuan”, “keratuan”, or “kraton”) as central to a land or realm (“bhumi”), which, in turn, formed the core of a larger, borderless, but concentric and hierarchically organized arrangement of authority. In this greater mandala, an Indic-influenced representation of a sort of idealized, “galactic” order, a ruler emerged from constellations of local powers and ruled by virtue of neither inheritance nor divine descent, but rather through a combination of charisma (“semangat”), strategic family relationships, calculated manipulation of order and disorder, and the invocation of spiritual ideas and supernatural forces. The exercise of power was never absolute, and would-be rulers and (if they were to command loyalty) their supporters had to take seriously both the distribution of benefits (rather than merely the application of force or fear) and the provision of an “exemplary center” enhancing cultural and intellectual life. In Mataram, overlords and their courts do not, for example, appear to have controlled either irrigation systems or the system of weekly markets, which remained the purview of those who dominated local regions (“watak”) and their populations. This sort of political arrangement was at once fragile and remarkably supple, depending on the ruler and a host of surrounding circumstances. *

See Separate Article: SAILENDRA DYNASTY: BUDDHISM, BOROBUDUR, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

Very little is known about social realities in Srivijaya and Mataram, and most of what is written is based on conjecture. With the exception of the religious structures on Java, these societies were constructed of perishable materials that have not survived the centuries of destructive climate and insects. There are no remains of either palaces or ordinary houses, for example, and we must rely on rare finds of jewelry and other fine metalworking (such as the famous Wonosobo hoard, found near Prambanan in 1991), and on the stone reliefs on the Borobudur and a handful of other structures, to attempt to guess what these societies may have been like. (The vast majority of these remains are Javanese.) A striking characteristic of both Srivijaya and Mataram in this period is that neither—and none of their smaller rivals—appear to have developed settlements recognizable as urban from either Western or Asian traditions. On the whole, despite evidence of socioeconomic well- being and cultural sophistication, institutionally Srivijaya and Mataram remained essentially webs of clanship and patronage, chieftainships carried to their highest and most expansive level. *

Sailendra and Mataram: Dual Dynasties or a Single Dynasty?

According to the Canggal inscription, Sanjaya ruled in the Mataram region in the vicinity of modern Yogyakarta and Prambanan. However, around the mid 8th century, the Sailendra dynasty emerged in Central Java and challenged Sanjaya domination in the region. Bosch in his book "Srivijaya, de Sailendravamsa en de Sanjayavamsa" (1952) suggested that the Buddhist Sailendra and the Shivaist Sanjaya dynasty (the Mataram kingdom) ruled Central Java together The Canggal inscription (A.D. 732) states that Sanjaya was an ardent follower of Shaivism. From its founding in the early 8th century until 928, the kingdom was ruled by the Sanjaya dynasty. [Source: metapedia.org]

The prevailing historical interpretation holds that the Sailendra dynasty co-existed next to the Sanjaya dynasty and the Mataram kingdom in Central Java, and much of the period was characterized by peaceful cooperation. The Sailendra, with their strong connections to Srivijaya, managed to gain control of Central Java and become overlords of the Rakai (local Javanese lords), including the Sanjayas, thus making the Sanjaya kings of Mataram their vassals. Little is known about the kingdom due to the dominance of the Sailendra. Around the middle of the 9th century, relations between the Sanjaya and the Sailendra deteriorated. In 852, the Sanjaya ruler, Pikatan, defeated Balaputra, the offspring of the Sailendra monarch Samaratunga and the princess Tara. This ended the Sailendra presence in Java; Balaputra retreated to the Srivijayan capital in Sumatra, where he became the paramount ruler. The Balaputra defeat and the victory of Pikatan was recorded in Shivagrha inscription dated 856, edicted by Rakai Kayuwangi, Pikatan's successor.

The dual Sailendra—Mataram dynasties theory proposed by Bosch and De Casparis has been opposed by some Indonesian historians. An alternate theory, proposed by Poerbatjaraka, suggests there was only one kingdom and one dynasty, the kingdom called Medang, with the capital in the Mataram area (thus the name of the kingdom: "Medang i Bhumi Mataram"), and the ruling dynasty being the Sailendra. This theory is supported with Boechari interpretation on Sojomerto inscription and Poerbatjaraka study on Carita Parahyangan manuscript, Poerbatjaraka holds that Sanjaya and all of his offspring belongs to the Sailendra family, which initially was Shivaist Hindu. However, according to Raja Sankhara inscription (now missing); Sanjaya's son, Panangkaran, converted to Mahayana Buddhism. And because of that conversion, the later series of Sailendra kings who ruled Mataram become Mahayana Buddhists also and gave Buddhism royal patronage in Java until the end of Samaratungga's reign. The Shivaist Hindus regained royal patronage with the reign of Pikatan, which lasted until the end of the Mataram Kingdom. During the reign of Kings Pikatan and Balitung, the royal Hindu Trimurti temple of Prambanan was built and expanded in the vicinity of Yogyakarta.

Mataram Kingdom Rule

Most of the time, the court of the Medang Kingdom was located in Mataram, somewhere on the Prambanan Plain near modern Yogyakarta and Prambanan. However, during the reign of Rakai Pikatan, the court was moved to Mamrati. Later, in the reign of Balitung, the court moved again, this time to Poh Pitu. Unlike Mataram, historians have been unable to pinpoint the exact locations of Mamrati and Poh Pitu, although most historians agree that both were located in the Kedu Plain, somewhere around the modern Magelang or Temanggung regencies. Later, during the reign of Wawa, the court was moved back to the Mataram area. [Source: metapedia.org ]

The common people of Mataram mostly made a living in agriculture, especially as rice farmers, however, some may have pursued other careers, such as hunter, trader, artisan, weaponsmith, sailor, soldier, dancer, musician, food or drink vendor, etc. Rich portrayals of daily life in 9th century Java can be seen in many temple bas-reliefs. Rice cultivation had become the base for the kingdom's economy where the villages throughout the realm relied on their annual rice yield to pay taxes to the court. Exploiting the fertile volcanic soil of Central Java and the intensive wet rice cultivation (sawah) enabled the population to grow significantly, which contributed to the availability of labor and workforce for the state's public projects. Certain villages and lands were given the status as sima (tax free) lands awarded through royal edict written in inscriptions. The rice yields from sima lands usually were allocated for the maintenance of certain religious buildings.

The bas-reliefs from temples of this period, especially from Borobudur and Prambanan describe occupations and careers other than agricultural pursuit; such as soldiers, government officials, court servants, massage therapists, travelling musicians and dancing troupe, food and drink sellers, logistics courier, sailors, merchants, even thugs and robbers are depicted in everyday life of 9th century Java. These occupations requires economy system that employs currency. The Wonoboyo hoard, golden artifacts discovered in 1990, revealed gold coins in shape similar to corn seeds, which suggests that 9th century Javan economy is partly monetized. On the surface of the gold coins engraved with a script "ta", a short form of "tail" or "tahil" a unit of currency in ancient Java.

The King was regarded as the paramount ruler or chakravartin, where the highest power and authority lies. The king, the royal family and the kingdom's officials had the authority to launch public projects, such as irrigation works or temple construction. The kingdom left behind several temples and monuments. The most notable ones are Prambanan, Sewu, and the Plaosan temple compound. The palace where the King resided was mentioned as kadatwan or keraton, the court was the center of kingdom's administration. Throughout its history, the center of Mataram kingdom was mostly situated in and around Prambanan Plain, named as Mataram, however during the reign of other kings, the capital may shifted to other places. Several other courts and capital cities were mentioned, such as Mamrati (Amrati) and Poh Pitu, location unknown but probably somewhere in Kedu Plain. In later Eastern Java period, other centers were mentioned; such as Tamwlang and Watugaluh (near Jombang), also Wwatan (near Madiun).

Mataram Culture

Since the beginning of its formation, the Mataram kings seemed to favour Shivaist Hinduism, such as the construction of Gunung Wukir Hindu temple as mentioned in Canggal inscription by king Sanjaya. However during the reign of Panangkaran and the rise of Sailendras influence, Mahayana Buddhism began to blossomed and gain court favour. The Kalasan, Sari, Mendut, Pawon and the magnificent Borobudur and Sewu temples testify the Buddhist renaissance in Central Java. The court patronage on Buddhism spanned from the reign of Panangkaran to Samaratungga. During the reign of Pikatan, Shivaist Hinduism began to regain court's favour, signified by the construction of grand Shivagrha (Prambanan). [Source: metapedia.org ]

The monumental Hindu temple of Prambanan in the vicinity of Yogyakarta — initially built during the reign of King Pikatan (838—850), and expanded continuously through the reign of Lokapala (850—890) to Balitung (899–911) — is a fine example of ancient Mataram art and architecture. (See Below). Other Hindu temples dated from Mataram Kingdom era are: Sambisari, Gebang, Barong, Ijo, and Morangan. Although the Shivaist regain the favour, Buddhist remain under royal patronage. The Sewu temple dedicated for Manjusri according to Kelurak inscription was probably initially built by Panangkaran, but later expanded and completed during Rakai Pikatan's rule, whom married to a Buddhist princess Pramodhawardhani, daughter of Samaratungga. Most of their subjects retained their old religion; Shivaist and Buddhist seems to co-exist in harmony. The buddhist temple of Plaosan, Banyunibo and Sajiwan were built during the reign of King Pikatan and Queen Pramodhawardhani, probably in the spirit of religious reconciliation after the battle of succession between Pikatan-Pramodhawardhani against Balaputra.

“From the 9th to mid 10th centuries, the Mataram Kingdom witnessed the blossoming of art, culture and literature, mainly through the translation of Hindu-Buddhist sacred texts and the transmission and adaptation of Hindu-Buddhist ideas. The bas-relief narration of the Hindu epic Ramayana was carved on the wall of Prambanan Temple. During this period, the Kakawin Ramayana, an old Javanese rendering was written. This Kakawin Ramayana, also called the Yogesvara Ramayana, is attributed to the scribe Yogesvara circa the 9th century CE, who was employed in the court of the Mataram in Central Java. It has 2774 stanzas in the manipravala style, a mixture of Sanskrit and archaic Javanese prose. The most influential version of the Ramayana is the Ravanavadham of Bhatti, popularly known as Bhattikavya. The Javanese Ramayana differs markedly from the original Hindu.

The name of the Mataram Kingdom was written in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription, dated 822 saka (900 CE), discovered in Manila, Philippines. The discovery of the inscriptions, written in the Kawi script in a variety of Old Malay containing numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements whose origin is ambiguous between Old Javanese and Old Tagalog, suggests that the people or officials of the Mataram Kingdom had embarked on inter-insular trade and foreign relations in regions as far away as the Philippines, and that connections between ancient kingdoms in Indonesia and the Philippines existed.

Mataram Kingdom Moves to East Java

During the first decades of the tenth century, Java’s center of political gravity shifted decisively from the island’s south-central portion to the lower valley and delta regions of eastern Java’s Brantas River. The move reflected the Sanjaya line’s long-term interest in eastward expansion, a reaction to increasingly frequent volcanic activity in central Java between the 880s and 920s, and economic rivalry with Srivijaya. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Around the year 929, the centre of the Mataram kingdom was shifted from Central Java to East Java by Mpu Sindok, who established the Isyana Dynasty. The exact cause of the move is still uncertain; however, a severe eruption of Mount Merapi volcano or a power struggle probably caused the move. Historians suggest that, some time during the reign of King Wawa of Mataram (924—929), Merapi volcano erupted and devastated the kingdom's capital in Mataram. The historic massive volcano eruption is popularly known as Pralaya Mataram (the death of Mataram). The evidence for this eruption can be seen in several temples that were virtually buried under Merapi's lahar and volcanic debris, such as the Sambisari, Morangan, Kedulan, and Pustakasala temples. Another theory suggests that the shift of capital city eastward was to avoid a Srivijaya invasion, or was motivated by economic reasons. The Brantas river valley was considered to be a strategic location for the control of maritime trade routes to the eastern parts of archipelago, being especially vital for control of the Maluku spice trade.[Source: metapedia.org ]

Eastern Java was a rich rice-growing region and was also closer to the source of Malukan spices, which had become trade items of growing importance. By the early eleventh century, Srivijaya had been weakened by decades of warfare with Java and a devastating defeat in 1025 at the hands of the Cola, a Tamil (south Indian) maritime power. As Srivijaya’s hegemony ebbed, a tide of Javanese paramountcy rose on the strength of a series of eastern Java kingdoms beginning with that of Airlangga (r. 1010–42), with its “kraton”at Kahuripan, not far from present-day Surabaya, Jawa Timur Province. A number of smaller realms followed, the best-known of which are Kediri (mid-eleventh to early thirteenth centuries) and Singhasari (thirteenth century), with their centers on the upper reaches of the Brantas River, on the west and east of the slopes of Mount Kawi (Gunung Kawi), respectively. *

Mataram Kingdom Collapses

Hinduism and Buddhism had developed as court cultures not accessible to common people. Indeed, many commoners had been severely exploited in constant, unpaid laboring to construct the Hindu–Buddhist megastructures of their kings. Buddhism and Hinduism, also, never took hold in eastern islands such as Sumba, Timor, and Flores. These islands had developed strong animistic cultures apart from the mainstream of world faiths and felt little need to change. In fact, outside religions posed a serious threat to their locally based power structures. House societies characterized the eastern islands, with ancestral homes as cosmological centers of people’s notions of the universe.

In the late 10th century, the rivalry between the Sumatran Srivijaya and Javanese Mataram became more hostile. The animosity was probably caused by the Srivijayan effort to reclaim Sailendra lands in Java, as Balaputra and his offspring — a new dynasty of Srivijaya maharajas — belonged to the Sailendra dynasty, or by Mataram aspirations to challenge Srivijaya dominance as the regional power. [Source: metapedia.org ]

In 990, Dharmawangsa launched a naval invasion of Srivijaya and unsuccessfully attempted to capture Palembang. Dharmawangsa's invasion caused the Maharaja of Srivijaya, Chulamaniwarmadewa to request protection from China. In 1006, Srivijaya managed to repelled the Mataram invaders. In retaliation, Srivijaya forces assisted Haji (king) Wurawari of Lwaram to revolt, and attacked and destroyed the Medang Palace, killing Dharmawangsa and most of the royal family. With the death of Dharmawangsa and the fall of the capital, under military pressure from Srivijaya, the kingdom finally collapsed. There was further unrest and violence several years after the kingdom's demise. Airlangga, a son of Udayana of Bali, also a nephew of Dharmawangsa, managed to escape capture and went into exile. He later reunited the remnants of the Mataram Kingdom and re-established the kingdom (including Bali) under the name of Kingdom of Kahuripan. In 1045, Airlangga abdicated his throne to resume the life of an ascetic. He divided the kingdom between his two sons, Janggala and Panjalu (Kediri) and from this point on, the kingdom was known as Kediri.

Prambanan Temple

Prambanan Temple (15 kilometers east of Yogyakarta) is the largest and most beautiful Hindu temple in Indonesia.. Named after the village where it is located, it was built in the 9th century 50 years after Borubudur and is known locally as the Temple of the Slender Virgin (Roro Jonggrang).Prambanan contains many lavish decorations and sexually-suggestive sculptures, scenes from the Ramayan and motifs that mix Hindu and Buddhist symbols. It has eight shrines which lie among green fields and villages.

The three main temples are dedicated to Hindu gods Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma. The biggest temple is dedicated to Shiva —the destroyer, and the two smaller ones which flank it on the east and west are dedicated to Brahma — the creator and Vishnu — the sustainer. The tallest temple of Prambanan—the main Shiva temple—is a staggering 47 meters (130 feet) high. Its peak is visible from far away and rises high above the ruins of the other temples.The temple across from the Shiva temple contains a fine image of a Nadi bull.

The main temple of Shiva houses the magnificent statue of a four-armed Shiva, standing on Buddhist-style lotus blossoms. In the northern cell is a fine image of Durga, Shiva’s consort. Some believe the Durga image is actually that of the Slender Virgin, who according to legend was turned to stone by a giant she refused to marry. The outsides are adorned with bas-reliefs depicting the Ramayana story.

Prambadan is surrounded by the ruins of 240 small “guard “ temples. Altogether there are 400 temples in the Prambadan area. Most are within five kilometers of Prambanan village and are generally not visited except by archeology nuts. But that is not to say they are not without merit. A good way to explore them is to rent a bicycle. The proximity of Prambanan and Buddhist Borobudur temple tells us that on Java, Buddhism and Hinduism lived peacefully next to one another.

See Separate Article PRAMBANAN TEMPLE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025