EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE

Medieval Sumatra was known as the “Land of Gold.” The rulers were reportedly so rich they threw solid gold bar into a pool every night to show their wealth. Sumatra was a source of cloves, camphor, pepper, tortoiseshell, aloe wood, and sandalwood—some of which originated elsewhere. Arab mariners feared Sumatra because it was regarded as a home of cannibals. Sumatra is believed to be the site of Sinbad’s run in with cannibals.

Sumatra was the first region of Indonesia to have contact with the outside world. The Chinese came to Sumatra in the 6th century. Arab traders went there in the 9th century and Marco Polo stopped by in 1292 on his voyage from China to Persia. Initially Arab Muslims and Chinese dominated trade. When the center of power shifted to the port towns during the 16th century Indian and Malay Muslims dominated trade.

Traders from India, Arabia and Persia purchased Indonesian goods such as spices and Chinese goods. Early sultanates were called “harbor principalities.” Some became rich from controlling the trade of certain products or serving as way stations on trade routes.

The Minangkabau, Acehnese and Batak— coastal people in Sumatra— dominated trade on the west coast of Sumatra. The Malays dominated trade in the Malacca Straits on the eastern side of Sumatra. Minangkabau culture was influenced by a series of 5th to 15th century Malay and Javanese kingdoms (the Melayu, Sri Vijaya, Majapahit and Malacca).

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

FIRST INDONESIAN KINGDOMS: HINDU-BUDDHIST INFLUENCES, SEAFARING, TRADE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

MATARAM KINGDOM: HISTORY, HINDUISM, PRAMBANAN, AFTERWARDS factsanddetails.com

SAILENDRA DYNASTY: BUDDHISM, BOROBUDUR, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

SINGHASARI, KEDIRI, MARCO POLO AND THE MONGOL INVASION OF JAVA factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

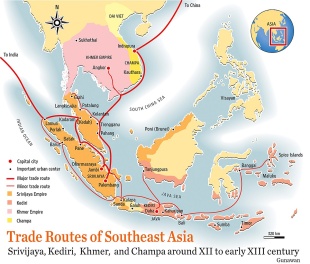

China and Indonesia Trade

Yvonne Tan wrote in the Asian Art Newspaper, Following the collapse of Tang control, overland routes to central Asia and the Arab world were increasingly insecure. China was forced turn to the South China Sea. Its Nanhai or 'Southern Seas' trade route might be considered a second Silk Road linking it with Southeast Asia and beyond. The Malay archipelago had been receptive already a few centuries before to cultural influences via maritime trade from both India and China. The transmission of Indic culture and the Hindu-Buddhist religion from the Indian subcontinent was most evident in Java and south Sumatra. Culturally Hindu-Buddhist, they also enjoyed trade and welcomed tribute missions from China. From the 7th to the 11th centuries, the Srivijayan kingdom in southeast Sumatra controlled maritime trade passing through the Malacca and the Sunda Straits. Known as Sanfoqi in Chinese, Srivijaya around present-day Palembang was a centre of Buddhist learning and an intermediary landing port for Chinese and other pilgrims travelling to India. Between 671 and 695, the Tang Chinese monk Yi Jing (635-713) journeyed to Nalanda in India and later visited Srivijaya from where he wrote a book entitled Records of Buddhist Practices from the South Seas. Buddhism in China was growing in importance and trade in Buddhist religious objects had already commenced by this time. In maritime southeast Asia, Srivijaya became a significant Chinese trading partner and a recipient of tribute. [Source: Yvonne Tan, Asian Art Newspaper May 2007 /]

“By the 10th century, Chinese maritime trade had extended beyond southeast Asia, linking it via the Indian Ocean to the Arab littoral and the ports of Siraf and Basra on the Persian Gulf and Suhar on the Gulf of Oman. Ten per cent of the cargo was devoted to glassware, gold and gemstones. While the advent of Islam in the Arab world after the mid-7th century favoured the use of the Arabic script in Koranic inscriptions, the 8th-century Arab conquest of Sind brought the faith closer to India. By the 10th century, Arabic had become the principal vernacular used in the Arab-Islamic empire but it was seafaring Muslim traders who brought Islam to the Malay archipelago. /

After the Mongol incursions in 1293, the early Majapahitan state did not have official relations with China for a generation, but it did adopt Chinese copper and lead coins (“pisis” or “picis” ) as official currency, which rapidly replaced local gold and silver coinage and played a role in the expansion of both internal and external trade. By the second half of the fourteenth century, Majapahit’s growing appetite for Chinese luxury goods such as silk and ceramics, and China’s demand for such items as pepper, nutmeg, cloves, and aromatic woods, fueled a burgeoning trade. [Source: Library of Congress *]

China also became politically involved in Majapahit’s relations with restless vassal powers (Palembang in 1377) and, before long, even internal disputes (the Paregreg War, 1401–5). At the time of the celebrated state-sponsored voyages of Chinese Grand Eunuch Zheng He between 1405 and 1433, there were large communities of Chinese traders in major trading ports on Java and Sumatra; their leaders, some appointed by the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) court, often married into the local population and came to play key roles in its affairs. *

See Separate Article: MARITIME-SILK-ROAD-ERA SHIPS, EXPORT PORCELAINS AND SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

Shipwrecks in Indonesian Waters

Intan Shipwreck (10th Century): The Intan Wreck was found by Indonesian fishermen only 10 miles from the Java Sea Wreck. The navy arrested the fishermen when they started to plunder the wreck, and gave the position to an Indonesian salvage licensee. Flecker carried out an investigation survey, and then directed the full excavation for a joint-venture incorporating the Indonesian licensee and the German company, Seabed Explorations, in 1997. The site turned out to be a magnificent find, the oldest Southeast Asian wreck with a complete cargo. Carbon dating augmented ceramic and coin analysis to confirm a 10th century AD date. While little of the hull remained, timber identification and structural details indicated that the ship was an Indonesian lashed-lug craft. She was probably bound from the Srivijayan capital, Palembang, to central or eastern Java.As the cargo was not too extensive, a low budget excavation was conducted from a modified fishing boat, with a second boat relaying the artefacts to Jakarta for conservation. Diving was by means of hooka with in-water decompression at this relatively shallow site, and excavation was carried out with water dredges. The recovered cargo was extremely diverse. It consisted of several thousand Chinese ceramics, Thai fine-paste-ware, base metal ingots of bronze, tin, lead and silver, Indonesian gold jewellery, bronze religious and utilitarian artefacts, Chinese mirrors, Arab glass, iron pots, and a wide range of organic materials. [Source: maritime-explorations.com =]

Java Sea Shipwreck (13th Century): The Java Sea Wreck was found and looted by fishermen before the location became known to a licensed salvage company in Indonesia. That company began excavation, but their barge nearly sunk on the wreck and there was insufficient funding to continue. Pacific Sea Resources then obtained the co-ordinates. Flecker directed the final thorough excavation for Pacific Sea Resources in 1996. The wreck is thought to be an Indonesian lashed-lug craft of the 13th century. She was voyaging from China to Java with a cargo of iron and ceramics. As much as 200 tonnes of iron was shipped in the form of cast iron pots and wrought iron bars. The original ceramics cargo may have amounted to 100,000 pieces. Approximately 12,000 intact or mostly intact Song dynasty ceramics were recovered, consisting primarily of celedon-type bowls and dishes from the kilns of southern China. There were also many covered boxes and jars, and an unusual painted ware with a lead-green glaze. Thai fine-paste-ware kendis and bottles were also found. =

Bakau Shipwreck (15th Century) is yet another fishermen find. It lies near the island of Bakau in Karimata Strait, Indonesia. Flecker visited this site in 1999, when very little of the original cargo remained. The wreck lay at the base of a reef, with a large coherent section of hull surviving. The hull was originally divided by bulkheads, and planks were edge-joined with diagonal iron spikes, a clear sign of Chinese construction. The ceramics cargo and carbon dating indicated a wreck of the early 15th century, which makes it one of the earliest examples of Chinese shipping in Southeast Asian waters. The main cargo on this ship consisted of very large storage jars of Thai origin. Indications are that they contained organic contents. There was also a selection of Chinese Longquan ware, Sukhothai and Sawankhalok ceramics, and some very delicate fine-paste-ware in the form of kendis.

Ninth-Century Chinese-Arab Belitung Shipwreck in Indonesia Waters

In 1998, sea cucumber divers working off Belitung, an island on the east coast of Sumatra, in the Java Sea, found some coral-encrusted ceramics, and further scraping away revealed a 9th century Arab dhow laden with 60,000 handmade ceramics and some pieces of gold and silver. Much of the cargo was made of up cheap, mass-produced, Chinese-made bowls, known as Changsa bowls, placed n large storage jars. There was also ink pots, spices jars of various sizes and ewers. [Source: Simon Worrall, National Geographic, June 2009]

The Belitung wreck was not only the oldest Arab vessel discovered in Asian waters, but it also contained the largest group of Tang dynasty artifacts ever found. The destination of the ship appeared to be Middle East, meaning that ship was traveling the maritime Silk Road. Many of the bowls were decorated with geometric decorations and Koranic motifs that were clearly intended for Middle Eastern market. This implied she objects were made to order for Middle Eastern customers. The dhow was almost 20 meters long. It resembled a kind of sailing dhow still used in Oman called a baitl qarib. Built of African and Indian wood, it had a raked prow and stern and was fitted with square sails and made of planks sewn together with coconut husks fiber.

Changsha bowl inscribed with a date: "16th day of the seventh month of the second year of the Baoli reign", or 826, roughly confirmed by radiocarbon dating of star anise at the wreck. The destination of the ship appeared to be Middle East, meaning that ship was traveling the maritime Silk Road. Many of the bowls were decorated with geometric decorations and Koranic motifs that were clearly intended for Middle Eastern market. This implied she objects were made to order for Middle Eastern customers.

Significance of the Belitung Shipwreck

Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop wrote in the New York Times, “For more than a decade, archaeologists and historians have been studying the contents of a ninth-century Arab dhow that was discovered in 1998 off Indonesia’s Belitung Island— one of the most important maritime discoveries of the late 20th century. The dhow was carrying a rich cargo “ 60,000 ceramic pieces and an array of gold and silver works “ and its discovery has confirmed how significant trade was along a maritime silk road between Tang Dynasty China and Abbasid Iraq. It also has revealed how China was mass-producing trade goods even then and customizing them to suit the tastes of clients in West Asia.[Source: Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, New York Times, March 7, 2011 |::|]

“Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds,” an exhibition that opened at the ArtScience Museum in Singapore in 2011 and was put together by the Asian Civilisations Museum in Singapore and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and Smithsonian Institution in Washington, featured many artifacts from the Belitung shipwreck. “This exhibition tells us a story about an extraordinary moment in globalization,” Julian Raby, director of the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, told the New York Times. “It brings to life the tale of Sinbad sailing to China to make his fortune. It shows us that the world in the ninth century was not as fragmented as we assumed. There were two great export powers: the Tang in the east and the Abbasid based in Baghdad.” |::|

“Until the Belitung find, historians had thought that Tang China traded primarily through the land routes of Central Asia, mainly on the Silk Road. Ancient records told of Persian fleets sailing the Southeast Asian seas but no wrecks had been found, until the Belitung dhow. Its cargo confirmed that a huge volume of trade was taking place along a maritime route, said Heidi Tan, a curator at the Asian Civilisations Museum and a co-curator of the exhibition. Mr. Raby said: “The size of the find gives us a sense of two things: a sense of China as a country already producing things on an industrialized scale and also a China that is no longer producing ceramics to bury.” He was referring to the production of burial pottery like camels and horses, which was banned in the late eighth century. “Instead, kilns looked for other markets and they started producing tableware and they built an export market.” |::|

See Separate Article: SILK ROAD DURING THE TANG DYNASTY (A.D. 618 - 907) factsanddetails.com

Artifacts from the Ninth-Century Belitung Shipwreck

By one estimate the treasures found in Belitung shipwreck were valued at $80 million. The merchant ship contained an impressive cargo, including an assemblage of lead ingots, bronze mirrors, spice-filled jars, intricately worked vessels of silver and gold, and approximately 60,000 glazed bowls, ewers and other ceramics. After its excavation, the cargo was sold to the Singaporean Government, which has loaned it indefinitely to the Singapore Tourism Board.

“Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds” featured only 450 of the 60,000 objects found in the shipwreck but the rows of similar bowls that were displayed underscored the importance and size of the find. Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop wrote in the New York Times, ‘stacked in the dhow, hundreds of tall stoneware jars each held more than a hundred nested Changsha bowls “ named after the Changsha kilns in Hunan where they were produced. Of the thousands of hand-painted pieces, almost all carry one of a few set patterns, but these were copied by many hands, resulting in an impression of huge variety. [Source: Sonia Kolesnikov-Jessop, New York Times, March 7, 2011 |::|]

“Not all of the ceramics were mass-produced. Among the most interesting pieces in the exhibition is an extremely rare dish, one of three found in the wreck, with floral lozenge motifs surrounded by sprigs of foliage. They are believed to be the earliest known complete Chinese blue-and-white ceramics. Ms. Tan, the curator, said: “It demonstrates that the Chinese potters were already experimenting with imported cobalt blue from Iraq, which they applied as underglaze painted decoration, some 500 years earlier than the famous blue and white porcelain of the 14th century.” At the time of the dhow’s discovery, cobalt-blue pigments had been found only in the Middle East, not yet in China, said Alan Chong, director of the Asian Civilisations Museum.

Aside from the rare ceramics, the haul also contained gold and silver objects, some of which Mr. Raby of the Smithsonian described as “of the very best quality you can see, clearly of imperial quality,” adding, “so we believe these were possible diplomatic gifts.” The form and decorative motifs of an octagonal gold cup “ musicians and dancers with long hair and billowing robes “suggest Central Asian metal wares. Mr. Raby said it was believed to be the largest known such gold cup from Tang China, even upstaging, he added, one of the great treasures of Tang gold and silver work: the so-called Hejiacun Hoard, found in what had been one of the southern suburbs of the Tang capital of Xian.

10th Century Cirebon Shipwreck

In February 2003, about 100 kilometers off Cirebon on the north Java coast, local fishermen caught ceramic objects in their dragnets. They were part of wreckage found at a depth of 56 meters in the Java Sea subsequently named the Cirebon cargo. The local Indonesian fisherman alerted divers and treasure hunters. The site was salvaged between April 2004 and October 2005. It took a team of international divers nearly 22,000 trips to recover the jewels and other goods buried with the boat. The first of these wares surfaced in April 2004. Providing evidence of a vigorous export trade was the largest amount of Yue wares or yue yao, found, forming 75 per cent of the cargo. Ten per cent of the 200,000 pieces was intact, including Yue ewers with bulging bellies, bowls, platters and incense burners as well as figurines of birds, deer and unicorns. [Source: Yvonne Tan, Asian Art Newspaper May 2007 /]

There was a great deal of trade between Arabia, India, Java and Sumatra in the 10th century, but even so, whoever was on that ship must have been a VIP based on exquisiteness of the porcelain found on board. Heymans speculates that all the Imperial porcelain suggests there was an ambassador on board. There was so much of it that when he first dove to the site, all he could see was a mountain of porcelain, no wood from the ship structure at all.

Yvonne Tan wrote in the Asian Art Newspaper, “A ceramic bowl inscribed with the date 968 and a company seal Xu Ji Shao, suggesting its manufacture, provide clues to the cargo's provenance. They suggest the cargo sank around 968 or after, in the late 10th century. China then witnessed the coexistence broadly, of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (906-960) with the Liao dynasty (916-1125) in the north. The Five Dynasties centring on the Yellow River were successive short-lived dynasties following one another. After the late Tang (618-906) uprisings of the 870s, regional divisions gave way to independent local regimes known as the Ten Kingdoms. The situation among the southern kingdoms was more stable, and less conflict enabled porcelain production and shipbuilding to advance along the coastal areas. /

“The salvage operation was completed in October 2005. The shipwreck vessel had a keel length of 24 meters and an overall length of 30 meters; a width of 12 meters; and the load was 200 - 300 metric tons of cargo. A third of the hull was in a condition, which enabled its construction technique to be examined. The vessel seems to have been constructed from dowelled planks and frames of the Southeast Asian or Austronesian-Srivijayan 'lashed lug' variety, supporting the case for local shipping power in the Malay archipelago. Lashed-lug vessels were constructed from lugs or projections in wooden planks, which had holes allowing the planks to be threaded together by coir fibre, rattan cords or cable. The planks were fastened by wooden dowels. Tenth-century Arab, Indian and Chinese sources have described Srivijaya as a major maritime centre in the Malay archipelago frequented by kunlun merchant ships. Kunlun was a term given to the peoples of the Nanhai, including Cham, Khmer, Malay, Srivijayan or Indian traders, some of whom sailed in lashed-lug vessels. /

“The position of the hull in the Java Sea suggests the vessel was veering towards the area of present-day Semarang in north Java. Several assumptions have been made concerning its itinerary. One possible origin was the western Indian Ocean with an intermediary port, believed to be Srivijaya, where some of the cargo might have been loaded. Kendi, or water jars, of perhaps Thai or Sumatran provenance were part of the cargo, indicating a Southeast Asian component. The substantial amount of Chinese ceramics in the cargo however suggests the vessel might have been to China, whose largest ports were then Quanzhou, Minzhou (present-day Ningbo) and Guangzhou. Fine harbours along Quanzhou on present-day Fujian's seaboard enjoyed active overseas trade and commercial exchanges with southeast, south and west Asia. Alternatively Guangzhou might have been the starting point of a route via the South China Sea to Champa, Tumasek (present-day Singapore) and Srivijaya. /

“The vessel sank in the Java Sea while heading towards Java. Metal, which comprised the remaining cargo, was dominated by bronze religious objects. Apart from Chinese bronze mirrors with I Ching trigram and astrological features, a bronze tripod for holding a water pot, a bronze lamp with an elephant rider, several candleholders, Indian Buddhist bells and figurines suggest Indian, Srivijayan or Javanese origins. Were these bronze objects destined for Southeast Asian temples? The significant amount of religious objects with Hindu-Buddhist motifs prompts speculation of possible tribute or exchange between the Wu Yue Kingdom, whose founding rulers were practising Buddhists, and Java. One chicken-shaped ewer with a handle representing the Hindu naga or serpent, bears the inscription, tianxia taiping, 'peace under heaven'. In the Javanese context, the Hindu-Buddhist complexes Prambanan and Borobudur had been constructed around 850 and circa 732-928, respectively, during the Central Javanese period, and were possible destinations for some of the religious paraphernalia. Remains of kitchen utensils and ceremonial objects bearing Hindu, Buddhist and Islamic features suggest the vessel carried crew of various nationalities and many faiths. /

The Karawang wreck, found in Indonesia waters and tentatively dated to the mid-late 10th century, appears to have been bound for Central or Eastern Java. Many of the ceramics are similar to those on the Cirebon wreck, but of lower quality and with no masterpieces. Coins are from the Kingdom of Min in Fujian, 916-946 and the demesne of Nanhan, around Guangzhou 917-971.

Treasures and Artifacts Found 10th Century Cirebon Shipwreck

Pieces found in Cirebon cargo include the largest known vase from the Liao Dynasty (907-1125) and famous Yue Mise wares from the Five Dynasties (907-960), with the green colouring exclusive to the emperor. Around 11,000 pearls, 4,000 rubies, 400 dark red sapphires and more than 2,200 garnets were also pulled from the depths by Belgian treasure-hunter Luc Heymans and his team of international divers. [Source: thehistoryblog.com May 2010]

Thehistoryblog.com reported: “Recovering the treasure turned out to be the least of Heymans’ difficulties. He had arranged permits for the excavation and retrieval of the shipwreck, but the Indonesian police still arrested two of the divers. They stayed in jail for a month while Heymans worked out the problem. Meanwhile, other treasure-hunters tried to poach the find, the Indonesian navy got all up in his grill and the government spent a couple of years drafting new legislation to deal with the discovery. Finally he cut a deal: the Indonesian government declared some of the treasure national heritage and therefore not salable, and it gets 50 percent of the sale proceeds from the rest of the treasure. So Heymans and his backers will have to settle for a mere $40 million at minimum. [Ibid]

Yvonne Tan wrote in the Asian Art Newspaper, ““The Yue ceramics found aboard might be attributed to the prosperous Wu Yue kingdom (907-978) on present-day southern Jiangsu and Zhejiang. These wares were believed to be the precursors to Chinese greenwares, associated with the Yue kiln complex active in Zhejiang from the Tang onwards. Controlled by the Wu Yue rulers who were the Qian family, the Yue kilns produced the 'first official ware' for the court. Also in the cargo were Northern white wares, comprising 2,500 dishes, bowls and jars that are subject to interpretation. [Source: Yvonne Tan, Asian Art Newspaper May 2007 /]

“Forty intact glass vessels among 2,000 glass shards, had constituents appearing very similar to glass from Syria or Persia under the Abbasid caliphate (circa 750-1258) of the Arab-Islamic empire. Blown in green, blue and turquoise, these light opaque glass vessels indicate possible Arab or Persian provenance. Syrian green glass of the same period has been described as imitating the colour of emeralds. Were these glass vessels used for religious rituals? Some objects in the Cirebon cargo bore obvious Arabic inscriptions. One stone mould was inscribed with Allahi Akbar, 'The One and Only God is Great' and Allah Malik Wahid Qahhar, 'The One and Only Dominator'. Gold objects in the Cirebon cargo include two gold plated daggers embellished with Arabic or Sunni-type inscriptions indicating possible Arab or Indian provenance. Gold items of jewellery include a chain belt, earrings and rings with Indian and Hindu-Buddhist motifs, embedded with semi-precious stones. A gold plated object with Javanese inscriptions has been described as an ancient Javanese amulet with mantras from Buddhist scriptures. Gemstones include rubies, probably from Ceylon, lapis lazuli and other semi-precious stones. /

“The Cirebon cargo was marked by its diversity. While dominated by Chinese ceramics, coinage, glass, gold, metalwork and lacquerware formed a small but significant part of it. Found in the wreck was Chinese copper coinage from the Nan Han kingdom (917-971) providing evidence of contact with the area of present-day Guangdong and Guangxi on the southern Chinese coast. The main currency zones of the Nan Han and the Min kingdom (909-945) in present-day Fujian were copper and lead based. During this period the Chinese monetary system had undergone a revolution as increased agricultural production and commerce encouraged the minting of various kinds of coinage. /

Effort to Sell the Treasure from the Cirebon Shipwreck

By one estimate the treasures found in Cirebon shipwreck were valued at $80 million. The cargo includes 250,000 pieces such as rubies, pearls, gold and jewelry, Iranian glassware and Chinese imperial porcelain, dating back to the end of the first millennium, or 967 AD. Luc Heymans, the Belgian director of Cosmix Underwater Research Ltd., the Dubai-based firm that excavated the haul, told AFP it was the largest ever found in Southeast Asia "in terms of both quality and quantity." The New York Times reported that a government auction house in Jakarta tried to sell the goods in 2010 but there were no buyers.

In May 2010, thehistoryblog.com reported: “A mind-bogglingly huge treasure trove found on a 1000-year-old shipwreck by Indonesian fishermen is going on sale in Jakarta. It’s the biggest treasure ever found in Asia, and comparable to the most valuable shipwreck ever found period, the Atocha, an early 17th century Spanish vessel found off the Florida coast. On sale will be 271,000 individual pieces, including precious gems, Iranian glassware and Imperial Chinese porcelain all dating back to the first millennium A.D. The estimated value of the auction is a staggering 80 million dollars. The pieces include the largest known vase from the Liao Dynasty (907-1125) and famous Yue Mise wares from the Five Dynasties (907-960), with the green colouring exclusive to the emperor. Around 11,000 pearls, 4,000 rubies, 400 dark red sapphires and more than 2,200 garnets were also pulled from the depths by [Belgian treasure-hunter Luc] Heymans and his team of international divers. [Source: thehistoryblog.com May 2010]

In May 2010, thehistoryblog.com reported: “A mind-bogglingly huge treasure trove found on a 1000-year-old shipwreck by Indonesian fishermen is going on sale in Jakarta. It’s the biggest treasure ever found in Asia, and comparable to the most valuable shipwreck ever found period, the Atocha, an early 17th century Spanish vessel found off the Florida coast. On sale will be 271,000 individual pieces, including precious gems, Iranian glassware and Imperial Chinese porcelain all dating back to the first millennium A.D. The estimated value of the auction is a staggering 80 million dollars.

In March 2012, the "Cirebon treasure" was put up for sale again. AFP reported: “The treasure shows objects being traded between the Far and Middle East, including carved rock and crystal typical of the Fatimid dynasty in Egypt, Mesopotamian drinking glasses, pearls from the Gulf, bronze and gold from Malaysia and exquisite Chinese imperial porcelain. After six years of red tape, the excavators finally gained permission to sell the treasure, although some of it was given to the Indonesian government. After it failed to find a buyer in Indonesia the treasure was exported to Singapore. The riches will be sold there "in a single batch so that a slice of history can be presented in its entirety as it deserves in a renowned museum", Heymans said. It will be a direct sale and not by auction. For Indonesia, this is the "first underwater archaeological excavation that is 100 percent legal, reconciling the preservation of heritage with the financial viability of this kind of operation", Heymans said. [Source: AFP, March 5, 2012]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025