EARLY INDONESIAN CULTURE

Although Indonesia is extremely diverse ethnically (more than 300 distinct ethnic groups are recognized), most Indonesians are linguistically--and culturally--part of a larger Indo-Malaysian world encompassing present-day Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines, and other parts of insular and mainland Asia. Early inhabitants had an agricultural economy based on cereals, and introduced pottery and stone tools during the period 2500 to 500 B.C. During the period between 500 B.C. and A.D. 500, as the peoples of the archipelago increasingly interacted with South and East Asia, metals and probably domesticated farm animals were introduced. [Source: Library of Congress]

The Dongson (Dong Son) culture from Vietnam and southern China made its way to Indonesia around 1000 B.C. It brought irrigated rice growing, bronze casting, ritual buffalo sacrifice and the practice of raising stone megaliths. Remnants of this culture can be found today in central Sulawesi, the Batak areas of Sumatra and parts of Borneo and the islands east of Bali.

Beginning around the 7th century B.C. organized societies began to take shape in different locations in Indonesia. These people practiced irrigated rice farming, used copper and bronze, domesticated pigs and other animals, practiced seafaring and established villages around rice fields. These early Indonesians were animists who believed in an afterlife not so different from their life on earth and were buried with tools and weapons they could use in the next world. [Source: Lonely Planet ++]

About A.D. 200 small states that were deeply influenced by Indian civilization began to develop in Southeast Asia, primarily at estuaries of major rivers. Such a state was founded near Jakarta in the A.D 4th century. The word Java is derived from the Sanskrit word “yava”, meaning “barely, grain.” The name is very old and appeared in Ptolemy’s “Geography” in the A.D. 2nd century. The first towns and small kingdoms appeared in Java around the A.D. 1st century. Small kingdoms were ruled by tribal leaders and organized around wet rice cultivation Around this time Indonesia began trading spices, gold and benzoin (an aromatic gum prized in China) with India and China and islands located on the major trade routes between India and China. ++

RELATED ARTICLES:

OLDEST CULTURES IN INDONESIA AND PEOPLE THERE BEGINNING 10,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

SRIVIJAYA KINGDOM: HISTORY, BUDDHISM, TRADE, ART factsanddetails.com

MATARAM KINGDOM: HISTORY, HINDUISM, PRAMBANAN, AFTERWARDS factsanddetails.com

SAILENDRA DYNASTY: BUDDHISM, BOROBUDUR, HISTORY factsanddetails.com

SINGHASARI, KEDIRI, MARCO POLO AND THE MONGOL INVASION OF JAVA factsanddetails.com

MAJAPAHIT KINGDOM: HISTORY, RULERS, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

EARLY INDONESIAN TRADE AND ANCIENT SHIPWRECKS factsanddetails.com

HISTORY OF ISLAM IN INDONESIA: ARRIVAL, SPREAD, ACEH, MELAKA, DEMAK factsanddetails.com

Early Agriculture in Indonesia

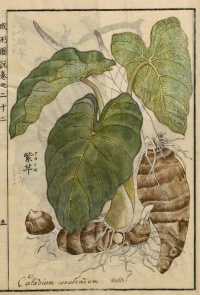

People in Indonesia may have been among the first to develop agriculture. There is some evidence of wild yam and taro cultivation dating back to 15,000 and 10,000 B.C. in Indonesia. Taro is one of the world's oldest cultivated crops, with evidence suggesting use or cultivation in Southeast Asia and the Pacific as far back as 28,000 to 10,000 years ago, though pinpointing a single origin is difficult; genetic studies point towards Southeast Asia, with potential domestication centers in India-Malaysia, while archaeological finds show early exploitation in places like Kuk Swamp, New Guinea (around 9000 B.C.) and Niah Caves, Borneo (10,000 years ago). Kiku Cave in the Solomon Islands show taro use up to 28,000 years ago, [Source: Google AI]

The earliest evidence suggests to West Africa was the primary center for yam domestication, with foraging of wild yams possibly starting 50,000 B.C.. and deliberate cultivation beginning around 5,000 B.C. (or as early as 11,000 years ago) for species like D. rotundata, while Southeast Asia saw separate domestication of Dioscorea alata (greater yam) around 3,000 B.C., becoming important for Austronesian seafaring cultures. Before formal farming, people gathered wild yams, learning to distinguish edible from poisonous types. Domestication likely started when gathered tubers were saved, sprouted, and replanted, with cultivation systems developing from these early practices.

The Indonesians have traditionally practiced two types of agriculture: wet-land rice farming, and slash and burn agriculture, known as “ladang”. Many Indonesians have traditionally grown rice in the wet season and another crop in the dry season. The earliest evidence of rice cultivation in Indonesia points to Sulawesi Island, with archaeological findings of rice phytoliths suggesting farming by at least 3,500 years ago (around 1500 BCE), possibly earlier, indicating a significant early agricultural presence in the archipelago, even as wild rice use might predate it.

According to Lonely Planet: “Java’s constant hot temperature, plentiful rainfall and volcanic soil was ideal for wet-field rice cultivation. The organisation this required may explain why the Javanese developed a seemingly more feudal society than the other islands. (Dry-field rice cultivation is much simpler, requiring no elaborate social structure to support it.)

Early Seafaring in Indonesia

The generally warm waters and rarity of storms in Indonesian seas provided favorable maritime environment. Boat building and navigation became highly advanced on islands such as Sulawesi, Bali, Java, and Sumatra, enabling extensive travel, inter-island trade, and long-distance migration across the region and beyond. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

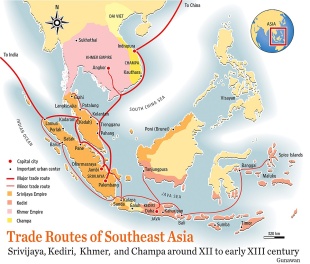

By the A.D. first century CE, India had already established sea trade with Java, and Indonesia’s outer islands were receiving goods from both India and China centuries before that. Because monsoon winds dictated the rhythm of travel in island Southeast Asia, traders moving between India and China often spent an entire season in ports near the Strait of Melaka, waiting for favorable winds to continue their journey. These monsoon-driven trade routes brought many Indian influences—and to a lesser extent Chinese ones—into the archipelago. Yet the same waters that facilitated commerce also protected the islands from the large-scale invasions that shaped political history on the mainland. As a result, Indonesian societies absorbed elements of major world civilizations—goods, technologies, new crops, religious ideas, agricultural techniques, domesticated animals, and cultural practices—gradually and on their own terms. Communities selectively adapted what they found useful.

One historical account of early Sumatran kingdoms notes that indigenous societies knew their past but felt little urgency to fix it into a single authoritative version. In a world where power was diffuse, where people were at home on the sea, and where agricultural settlements were scattered along countless rivers, history was flexible rather than rigidly codified. Consequently, few early written records from the Indonesian region survive, though some originate from Bali, Java, and Sulawesi. Additional details come from outside observers—Chinese envoys and, much later, Europeans such as Marco Polo—who described life in the archipelago’s bustling ports and cosmopolitan centers. Sumatra and Java, in particular, became major hubs of international trade and political power, enriched by well-developed Hindu–Buddhist states that drew foreign merchants and emissaries.

Early Trade in Malaysia and Indonesia

Little is known about Indonesia’s early history, but historians believe that as early as the first few centuries A.D. trade on the Strait of Malacca helped to create economic and cultural links among China, India, and the Middle East. Among the most powerful and enduring early kingdoms was Srivijaya, which ruled much of Indonesia and peninsular Malaysia from the seventh to the fourteenth century with support from China and the Orang Laut (“men of the sea”) who originated from Peninsular Malaysia and were perhaps the region’s best sailors and fighters.

By the A.D. 2nd century. Europeans were familiar with Malaya, and Indian traders had made regular visits in their search for gold, tin and jungle woods. Describing the trade on Malacca Strait, Prof. Dr. Nazeer Ahmed, PhD wrote in the Encyclopedia of Islamic History:“Sandwiched between the island of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, the Strait of Malacca is the artery for commerce between China, Japan, India, Arabia and East Africa. In the Middle Ages, these Straits were the hub for trade and commerce just as much as they are today. Riding on the monsoons, ships from as far away as Canton, China visited Malacca from January to May. From July onwards, the monsoons reversed the flow of winds, facilitating the return of ships to India and Sri Lanka. The monsoon patterns in the Arabian Sea similarly allowed ships from Aden and East Africa to trade with Gujrat and the Malabar Coast of India.

“Through the ages, ships have used the coast of this peninsula to dock and transact business. If one were to visit this area around the year 1400, one would find Chinese, Indians, Omanis, Yemenis, Persians and Africans intermingling with traders from Sumatra, Java, Bali and Canton, exchanging goods and establishing trade relations. China exported silk, brocades, porcelain and perfumes. India offered hardwoods, carvings, precious stones, cotton, sugar, livestock and weapons. From the interior of Malaya came tin, camphor, ebony and gold. Sumatra provided rice, gold, black pepper and mace. Java was the source of dyes, spices and perfumes. Cloves were exported from the Malaccas and sandalwood came from Timor. Ceramics from China were a major commodity.

“Muslim merchants dominated international trade in the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal and the East China Sea. A common religion, impeccable business integrity and universal transaction laws based on the Shariah had enabled the Muslims to establish a trade network linking the coastlines of East Africa, southern Arabia, the Persian Gulf and the Malabar coast with the islands of Indonesia and the southern coast of China. As early as the 8th century, there was a Muslim trading post in Canton. The coastline of Malaya was cosmopolitan wherein merchants from Malabar, Arabia and Africa lived and interacted with the indigenous Malay population and Chinese mandarins.”

Early sultanates were called “harbor principalities. Some became rich from controlling the trade of certain products or serving as way station on trade routes. The Malay Peninsula was known to ancient Tamils as Suvarnadvipa or the "Golden Peninsula". It was shown on Ptolemy's map as the "Golden Khersonese". He referred to the Straits of Malacca as Sinus Sabaricus. Trade relations with China and India were established in the 1st century BC. [Source: Wikipedia]

Earliest Historical Records of Indonesia

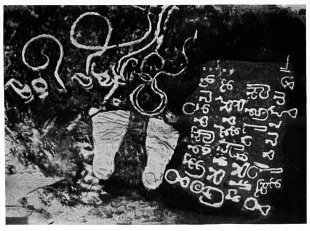

Although some Indonesian peoples probably began writing on perishable materials at an earlier date, the first stone inscriptions (in Sanskrit using an early Pallava script from southern India) date from the end of the fourth century AD (in the eastern Kalimantan locale of Kutai) and from the early or mid- fifth century AD (in the western Java polity known as Taruma). These inscriptions offer a glimpse of leaders newly envisioning themselves not as mere chiefs (“datu”) but as kings or overlords (“raja, maharaja”), taking Indic names and employing first Brahmanical Hindu, then Buddhist, concepts and rituals to invent new traditions justifying their rule over newly conceived social and political hierarchies. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In addition, Chinese records from about the same time provide scattered, although not always reliable, information about a number of other “kingdoms” on Sumatra, Java, southwestern Kalimantan, and southern Sulawesi, which, in the expanding trade opportunities of the early fifth century, had begun to compete with each other for advantage, but we know little else about them. Historians have commonly understood these very limited data to indicate the beginnings of the formation of “states,” and later “empires” in the archipelago, but use of such terms is problematic.*

We understand that small and loosely organized communities consolidated and expanded their reach, some a great deal more successfully than others, but even in the best-known cases we do not have sufficient specific knowledge of how these entities actually worked to compare them confidently with, for example, the states and empires of the Mediterranean region during the same period or earlier. More generalized terms, such as “polities” or “hegemonies,” are suggestive of social and political models that are more applicable. *

Recorded accounts of Sumatra date back to the period of trade by Baghdad merchants with India and China, by way of Southeast Asia. Suleyman (851) first wrote about Nias island and described it “to contain an abundance of gold. The inhabitants live off the fruit of the coconut tree, from which they make palm wine, and cover their bodies with coconut oil. When someone wants to get married, he must bring the head of an enemy. If he has killed two enemies, he may take two wives. If he has killed fifty enemies, he may take fifty wives.” Other early accounts of Nias Island include: “The Book of Indian Wonders” (“Kitab adaib al-Hind”), dated by Van der Lith to the year 950; the writings of the famous geographer Edrisi (1154); a description of cannibals inhabiting the island by Kazwini (1203–1283); accounts by Rasid Ad-Din (1310); and descriptions of a large island city by Ibn Al-Wardi (1340). [Source: Viaro, Mario Alain, “Ceremonial Sabres of Nias Headhunters in Indonesia” , Arts et cultures. 2001, vol. 3, p. 150-171]

Arrival of Hinduism and Buddhism in Indonesia

In ancient times most people who lived in what is now Indonesia most likely practiced some form of animism (belief in spirits) and ancestor worship. Perhaps, as is true some Indonesian animists today, many of their beliefs were tied to making sure that ancestors rest in peace, harvests were good and people had enough to eat and maintained good health. Animists remain in West Papua and Sumba.

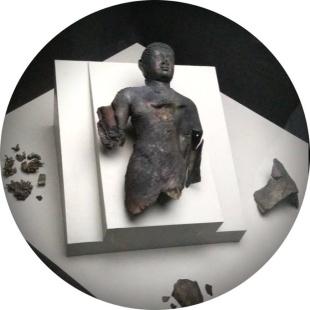

Buddhism and Hinduism arrived in the A.D. 2nd, 3rd and 4th centuries presumably as traders from India and other places arrived on Indonesian islands and brought their religions with them. There are numerous Buddhist and Hindu sites in Indonesia. The oldest Buddha statue in Indonesia was found in Sulawesi dated to the A.D. 2nd century. The oldest Hindu art in Indonesia are Hindu statues found in Sumatra and Sulawesi dated to the A.D. 3rd century. Hindu Sanskrit inscriptions dated to the A.D. 5th century have been found in West Java and eastern Kalimantan. Early Indonesian rulers were regarded as incarnations of the Hindu god Vishnu. Some scholars believe that early Indonesian kings invited Hindu priests from India to provide them with mystical powers and a spiritual justification for their rule.

Buddhism was introduced to Java by the A.D. fifth century and established in Sumatra in the 7th century. It took hold to a lesser extent in Malaysia and Borneo and remained strong until the massive conversion to Islam in the 15th century. Buddhism existed peacefully with Hinduism and indigenous magical beliefs. Buddhism grew from Hindusim in India. In Indonesia the two religions have often been interwoven with each other and with traditional Javanese beliefs. Hindu statues sometimes have Buddhist symbols and Buddhist temples often have depictions of Hindu gods.

Before Islam became dominate, Indonesia was ruled by a succession of Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms for over a thousand years. Buddhism and Hinduism were embraced by Indonesian royalty and, some speculate, they were used to justify the rule of Indonesian leaders with the god-king beliefs. Many believe they were practiced by royals and elite while ordinary people kept their traditional religion. Many events in the great Hindu epic the Ramayana take place in Java. For the most part Hinduism and Buddhism developed as court cultures inaccessible to commoners. Indeed, many commoners were severely exploited through constant, unpaid labor to build their kings' Hindu-Buddhist megastructures. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Spread of Indian Civilization

During the early centuries A.D., elements of Indian civilization, especially Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism, were brought to Sumatra and Java and stimulated the emergence of centralized states and highly organized societies. Scholars disagree on how this cultural transfer took place and who was involved. Apparently, traders and shippers, not just Indian but Indonesian as well, were primarily responsible. Small indigenous states existed in the coastal regions of western Indonesia at a time when Indian Ocean trade was flourishing. [Source: Library of Congress *

But, unlike the Islamic culture that was to come to Indonesia nearly 1,000 years later, India in the first centuries A.D. was divided into a rigid caste hierarchy that would have denied many features of Indian tradition to relatively low-caste merchants and sailors. Historians have argued that the principal agents in Indianization were priests who were retained by indigenous rulers for the purpose of enhancing their power and prestige. Their role was largely, although not exclusively, ideological. In Hindu and Buddhist thought, the ruler occupied an exalted position as either the incarnation of a god or a bodhisattva (future Buddha). This position was in marked contrast to the indigenous view of the local chief as merely a "first among equals." Elaborate, Indian-style ceremonies confirmed the ruler's exalted status. Writing in Sanskrit brought literacy to the courts and with it an extensive literature on scientific, artistic, political, and religious subjects. *

Some writers are skeptical about the role of priests because high-caste Brahmins would have been prohibited by Brahmanic codes from crossing the polluting waters of the ocean to the archipelago. Some must have gone, however, probably at the invitation of Southeast Asian courts, leading to the hypothesis that Hinduism may indeed have been a proselytizing religion. In the early nineteenth century, the British faced mutinies by their high-caste Indian troops who refused to board ships to fight a war in Burma. Perhaps such restrictions were less rigid in earlier times, or the major role in cultural diffusion was played by Buddhists, who would not have had such inhibitions. *

Although the culture of India, largely embodied in insular Southeast Asia with the Sanskrit language and the Hindu and Buddhist religions, was eagerly grasped by the elite of the existing society, typically Indian concepts, such as caste and the inferior status of women, appear to have made little or no headway against existing Indonesian traditions. Nowhere was Indian civilization accepted without change; rather, the more elaborate Indian religious forms and linguistic terminology were used to refine and clothe indigenous concepts. In Java even these external forms of Indian origin were transformed into distinctively Indonesian shapes. The tradition of plays using Javanese shadow puppets (wayang), the origins of which may date to the neolithic age, was brought to a new level of sophistication in portraying complex Hindu dramas (lakon) during the period of Indianization. Even later Islam which forsakes pictorial representations of human brings, brought new developments to the wayang tradition through numerous refinements in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries.*

Earliest Hindu-Buddhist Malay Kingdoms

The earliest Hindu-Buddhist Malay kingdoms, emerging from Indian cultural influence via trade routes around the A.D. 2nd-3rd centuries, include Langkasuka (Pattani region) and Kedah (Kadaram), both significant early centers on the Malay peninsula, with the Bujang Valley (Kedah) showing extensive archaeological evidence of early Indianized polities, including iron smelting from as early as A.D. 110, setting the stage for later powers like Srivijaya and Majapahit. [Source: Google AI]

The earliest Hindu-Buddhist Malay kingdoms in Indonesia emerged from the 4th century, with Kutai Martadipura in Borneo (4th century) often cited as the first due to its inscriptions. Following this, the powerful Srivijaya empire (7th-13th centuries) based in Sumatra became a major Buddhist maritime power controlling vital trade routes, while Javanese kingdoms like Kalingga (6th-7th centuries) and the later Mataram Kingdom (8th-10th centuries) were significant Hindu-Buddhist states in Central Java, influencing the region deeply before the rise of Majapahit.

The earliest Hindu-Buddhist Malay kingdoms in Sumatra emerged from Indianization via trade, with Srivijaya (Palembang) being the first major, famous kingdom (6th-7th centuries), a dominant maritime Buddhist empire controlling trade routes, followed by the indigenous Melayu Kingdom (Dharmasraya/Jambi) which Srivijaya absorbed and later re-emerged, establishing the core of Malay culture influenced by both faiths, long before Islam's rise.

The first Hindu kingdom—Melayu—was established on Java in A.D. 400. Indian influence between the 8th and 14th century produced a number of small Shaivite-Buddhist kingdoms. In the 7th century the Buddhist Sriwijaya Empire ruled Western Indonesia and controlled trade in much of the area. In the 9th century the Hindu Mataram Kingdom ceded control to the Buddhist Sailendra Kingdom. The effect of India on Indonesia was quite profound but greatly modified. When the great Indian poet Rabindranth Tagore visited Java he said, “I see India everywhere but I do not recognize it.”

Hinduism and Buddhism had developed as court cultures not accessible to common people. Indeed, many commoners had been severely exploited in constant, unpaid laboring to construct the Hindu–Buddhist megastructures of their kings in later kingdoms. Buddhism and Hinduism, also, never took hold in eastern islands such as Sumba, Timor, and Flores. These islands had developed strong animistic cultures apart from the mainstream of world faiths and felt little need to change. In fact, outside religions posed a serious threat to their locally based power structures. House societies characterized the eastern islands, with ancestral homes as cosmological centers of people’s notions of the universe.

Tarumanagara, the Earliest Hindu-Buddhist Kingdom in Java

Tarumanagara — also known as the Taruma Kingdom or simply Taruma — was an early Sundanese, Indianised polity in western Java. Regarded as the earliest Hindu-Buddhist kingdom in Java, it was lead by the 5th-century ruler, King Purnawarman, who left the earliest known inscriptions in Java, dated to around A.D. 358. At least seven stone inscriptions linked to Tarumanagara have been found across western Java, particularly near Bogor and Jakarta. These include the Ciaruteun, Kebon Kopi, Jambu, Pasir Awi, and Muara Cianten inscriptions near Bogor; the Tugu inscription in Cilincing, North Jakarta; and the Cidanghiang inscription in Lebak village, Munjul district, south of Banten. Tarumanagara is believed to have flourished between roughly A.D. 358 and 669 CE in western Java, in an area encompassing present-day Bogor, Bekasi, and Jakarta—essentially the region of modern Greater Jakarta. [Source: Wikipedia]

Eric A. Powell wrote in Archaeology magazine: In the early first millennium A.D., as merchants sailing the Maritime Silk Road between India and China traversed the Strait of Malacca, they brought with them not only great wealth but also the Hindu and Buddhist faiths, which spread along the coasts of modern-day Indonesia and Malaysia. Sanskrit stone inscriptions dating to about A.D. 450 found near the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, show that some people on the northern coast of Java had converted to Hinduism by that time. Researchers believe that the Kingdom of Taruma ruled the northern coast of Java from about A.D. 380 to 669. At that point it was absorbed into the growing Buddhist Srivijaya Empire (ca. A.D. 600–1200), which controlled the lucrative maritime trade for several more centuries. [Source:Eric A. Powell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2024]

Many scholars believe that the punden berundak on Java largely date to the period when Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms were flourishing thanks to the influx of resources brought via the Maritime Silk Road. Punden Berundak is an ancient Indonesian sacred architectural form from the megalithic era, resembling a step pyramid or terraced structure, symbolizing the ascent to the spirit world for ancestor worship, often found in ancient temples (Pura) like Pura Penulisan in Bali, signifying revered high places for ancestral spirits. It's a spiritual mountain-like structure with receding platforms, built from stone, and serves as a sacred site to honor ancestors.

Merchants would have traded iron goods and textiles from India and China for gold and precious wood supplied by the peoples of interior Java. It’s possible that construction and maintenance of megalithic sites such as Gunung Padang on Java were enabled by the new levels of prosperity among inland peoples resulting from this trade. Two other substantial megalithic sites constructed in this period are Cipari, which is made up of two large stone tombs next to two stone circles about 20 feet in diameter, and Pangguyangan, a pyramidal temple consisting of seven terraces, which now has an Islamic burial at its top.

Until Islam spread to the interior of Java in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, leaders of highland clans used their wealth to mobilize their followers and recruit people from other clans to build megalithic monuments during festivals. At these days-long events, goods were redistributed among many communities. These gifts bound people together in complicated webs of obligation that shored up the social order. Though these festivals faded away once people converted to Islam, archaeologists believe they were similar to celebrations that are still held in remote regions of Indonesia.

Purnawarman is regarded as Tarumanagara’s first and greatest ruler. According to the Tugu inscription, he ordered the construction of a canal that altered the course of the Cakung River and helped drain coastal lowlands for farming and settlement. In his inscriptions, he likens himself to the god Vishnu, while Brahmins are recorded as performing rituals to consecrate the hydraulic work. One inscription on Purnawarman translates as: The name of the king who is famous of faithfully executing his duties and who is incomparable (peerless) is Sri Purnawarman who reigns Taruma. His armour cannot be penetrated by the arrows of his enemies. The prints of the foot soles belong to him who was always successful to destroy the fortresses of his enemies, and was always charitable and gave honorable receptions to those who are loyal to him and hostile to his enemies.”

Indianized Empires in Indonesia

Although historical records and archaeological evidence are scarce, it appears that by the seventh century A.D., the Indianized kingdom of Srivijaya, centered in the Palembang area of eastern Sumatra, established suzerainty over large areas of Sumatra, western Java, and much of the Malay Peninsula. Dominating the Malacca and Sunda straits, Srivijaya controlled the trade of the region and remained a formidable sea power until the thirteenth century. Serving as an entrepôt for Chinese, Indonesian, and Indian markets, the port of Palembang, accessible from the coast by way of a river, accumulated great wealth. A stronghold of Mahayana Buddhism, Srivijaya attracted pilgrims and scholars from other parts of Asia. These included the Chinese monk Yijing, who made several lengthy visits to Sumatra on his way to India in 671 and 695, and the eleventh-century Buddhist scholar Atisha, who played a major role in the development of Tibetan Buddhism. [Source: Library of Congress *]

During the early eighth century, the state of Mataram controlled Central Java, but apparently was soon subsumed under the Buddhist Sailendra kingdom. The Sailendra built the Borobudur temple complex, located northwest of Yogyakarta. The Borobudur is a huge stupa surmounting nine stone terraces into which a large number of Buddha images and stone bas-reliefs have been set. Considered one of the great monuments of world religious art, it was designed to be a place of pilgrimage and meditation. The basreliefs illustrate Buddhist ideas of karma and enlightenment but also give a vivid idea of what everyday life was like in eighthcentury Indonesia. Energetic builders, the Sailendra also erected candi, memorial structures in a temple form of original design, on the Kedu Plain near Yogyakarta. *

The late ninth century witnessed the emergence of a second state that is noted for building a Hindu temple complex, the Prambanan, which is located east of Yogyakarta and was dedicated to Durga, the Hindu Divine Mother, consort of Shiva, the god of destruction. From the tenth to the fifteenth centuries, powerful Hindu-Javanese states rivalling Srivijaya emerged in the eastern part of the island. The kingdom of Kediri, established in eastern Java in 1049, collected spices from tributaries located in southern Kalimantan and the Maluku Islands, famed in the West as the Spice Islands or Moluccas. Indian and Southeast Asian merchants among others then transported the spices to Mediterranean markets by way of the Indian Ocean. *

The golden age of Javanese Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms was in the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Although the eastern Javanese monarch Kertanagara (reigned 1268-92) was killed in the wake of an invasion ordered by the Mongol emperor Khubilai Khan, his son-in-law, Prince Vijaya, established a new dynasty with its capital at Majapahit and succeeded in getting the hard-pressed Mongols to withdraw. The new state, whose expansion is described in the lengthy fourteenth-century Javanese poem Nagarakrtagama by Prapanca, cultivated both Shivaite Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism. It established an empire that spread throughout much of the territory of modern Indonesia. *

The empire building was accomplished not by the king but by his prime minister, Gajah Mada, who was virtual ruler from 1330 to his death in 1364. Possibly for as long as a generation, many of the Indonesian islands and part of the Malay Peninsula were drawn into a subordinate relationship with Majapahit in the sense that it commanded tribute from local chiefs rather than governing them directly. Some Indonesian historians have considered Gajah Mada as the country's first real nation-builder. It is significant that Gadjah Mada University (using the Dutch-era spelling of Gajah Mada's name), established by the revolutionary Republic of Indonesia at Yogyakarta in 1946, was--and remains--named after him. *

By the late fourteenth century, Majapahit's power ebbed. A succession crisis broke out in the mid-fifteenth century, and Majapahit's disintegration was hastened by the economic competition of the Malay trading network that focused on the state of Melaka (Malacca), whose rulers had adopted Islam. Although the Majapahit royal family stabilized itself in 1486, warfare broke out with the Muslim state of Demak and the dynasty, then ruling only a portion of eastern Java, ended in the 1520s or 1530s. *

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Ministry of Tourism, Republic of Indonesia, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated December 2025