MADURESE

The Madurese are an ethnic group that hail from Madura, a dry, inhospitable island off the northeast coast of Java, and have traditionally made their living off the island. Also known as the Orang Madura, Tijang Madura and Wong Madura, they are regarded by many Indonesians with the same contempt leveled at gypsies in Europe. The Javanese call them “kasar” (“unrefined”). Madurese men are often identified with the clurit, a distinctive sickle-shaped knife that holds strong cultural meaning, and with traditional clothing marked by bold red-and-white stripes. These colors are traced to the naval banner of the Majapahit Empire, the eastern Javanese kingdom that once ruled Madura Island. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; Wikipedia]

The Madurese (pronounced MAHD-oo-reez) have traditionally worked as farmers, traders, livestock producers and fishermen. They have long been resistant to outsiders and their history has been defined by struggles with the Javanese. In 1677 the Madurese managed to seize the royal treasury of the Javanese Mataram kingdom and the Javanese needed the help of the Dutch to get it back. The adoption of Islam in the 16th century helped the Madurese unify as a people. The Dutch used the Madurese as mercenaries and tapped anti-Javanese feeling among the Madurese in their battles again the Javanese .

Despite their ancestral island lying only a short distance from Surabaya on Java, the Madurese have long maintained a cultural identity distinct from their Javanese neighbors. Their history is closely intertwined with Java’s, yet marked by repeated assertions of autonomy and difference. Madurese cuisine is well known in Indonesia and the Madurese are regarded as the inventors of satay and pencak silat, a traditional martial art. They are also known as the largest owners of traditional grocery shops in Indonesia and famous for Karapan sapi bull races. Historically, this group has played a pioneering role in classical Islamic movements in Indonesia. Pondok Pesantren have long served as key centers for Madurese Muslims to study and transmit Islamic learning, particularly forms rooted in Indonesian Islam.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MADURESE LIFE AND SOCIETY: FAMILES, CULTURE, BULL RACING factsanddetails.com

VIOLENCE AGAINST THE MADURESE IN BORNEO factsanddetails.com

EAST JAVA: SIGHTS, INTERESTING AND IMPORTANT PLACES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON JAVA factsanddetails.com

Madurese Language

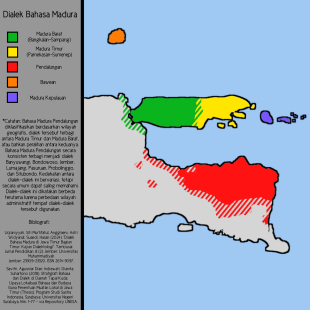

The Madurese language is an Austronesian language. Although it is closely related to Javanese and Sundanese, it is not mutually intelligible with them. It is divided into three major dialects centered on Bangkalan, Pamekasan, and Sumenep, from east to west. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The language's traditional script, a version of the Javanese script, is in decline due to competition from the Latin alphabet used for Bahasa Indonesia. Like Javanese, Madurese has three levels of formality: informal (Enja'-iya, named after the words for "yes" and "no"), polite (Enghi-enten), and highly deferential (Enghi-bhunten).

In parts of East Java, many Madurese speak a mixed Madurese–Javanese variety, reflecting long contact between the two groups. Alongside these local languages, most Madurese are also fluent in Bahasa Indonesian, the national language. Recognized dialects include Sumenep (the standard dialect), Sampang, Pamekasan, Bangkalan, Bawean, and Sapudi. In eastern Java, highly mixed forms—often grouped under the Pendalungan dialect chain—are spoken in areas such as Jember, Lumajang, Malang, Pasuruan, Situbondo, Banyuwangi, Probolinggo, and Bondowoso. Additional regional varieties include the Giliraja–Raas dialect spoken in the Sumenep archipelago, while Kangean is considered a separate language rather than a Madurese dialect. [Source: Wikipedia]

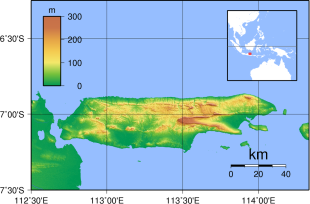

Madura Island

Madura (a short ferry ride across the Strait of Madura from Surabaya) is an island off the coast of Java that measures 35 by 160 kilometers. It is the homeland of the Madurese and is famous for its bull races held each year after the harvest. About 3.6 million to 4 million Madurese live on the island. More than three times that number live elsewhere in Indonesia. Only a handful on Non-Madurese live on Madura. The climate on the island is much drier than that on Java. The northern part of the islands has cliffs and sand dunes. The southern part has some cultivated lowlands. The main industries are cattle raising, salt and fishing.

Tourists generally don’t visit Madura except during the bull racing season. A 30-minute ferry that runs roughly every 30 minutes connects the western Madurese town of Kamal with Surabaya’s Tunjung Perak harbor. Places worth a look in Madura include Bangklan, with a museum devoted to Madurese culture; the tobacco farms around Waru; the salt farms around Kalianget; and the fishing towns of the north coast with nice beaches and fishing villages with brightly painted perahu (fishing boats). Sumenep was the home of the Madurese royalty. Inside the Kraton there is a museum with possessions of the royal family.

See Separate Article: EAST JAVA: SIGHTS, INTERESTING AND IMPORTANT PLACES factsanddetails.com

History of Madura and the Madurese

In the 14th century, Madura formed part of the Majapahit Empire before later developing its own political structures following the spread of Islam in the 16th century. Madura subsequently fell under the influence of the Javanese kingdom of Mataram Sultanate, against which the Madurese rebelled in the 17th century. Although the revolt—led by Prince Trunojoyo—briefly devastated Mataram’s capital, it was ultimately crushed by the Dutch East India Company, ushering in a long period of Dutch dominance. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Madura’s strategic position, guarding the approaches to the Brantas and Bengawan Solo river deltas, ensured its continuing importance despite the island’s limited economic resources. Eastern Madura passed formally into VOC control in 1743, and by 1885 the entire island was under direct Dutch rule. Although spared the Forced Cultivation System, Madura suffered economic decline, heavy taxation, and recurring famine. Madurese rulers nevertheless supported Dutch imperial campaigns by supplying soldiers for colonial armies across the archipelago. The island endured particular hardship during the Japanese occupation (1942–45). After World War II, Dutch attempts to establish a client state failed, and Madura was incorporated into the Republic of Indonesia in 1950. Persistent economic stagnation since independence has driven widespread out-migration. Large Madurese communities formed along the north coast of East Java and in transmigration areas such as Kalimantan, where tensions culminated in violent Madurese–Dayak conflicts in the late 1990s.

Environmental constraints have long shaped Madurese life. Much of Madura lacks irrigation suitable for wet-rice farming, and its calcium-rich soils limit productivity. These conditions encouraged migration even in the colonial period; by 1930, more Madurese lived on Java than on Madura itself. Modernization and Islamic reform have also influenced Madurese society. Urban lifestyles increasingly mirror national patterns centered on Jakarta, while reformist Islam promotes stricter, more orthodox practices. Infrastructure development—most notably the bridge linking Surabaya and Bangkalan—has accelerated Madura’s integration into the Surabaya metropolitan area, transforming western Madura into a commuter and industrial extension of Indonesia’s second-largest city.

Madurese Population

The Madurese are a fairly large group. They make up about 3 percent of the population of Indonesia and are recognized as the country’s fourth largest ethnic group after the Javanese, Sundanese and Batak. The Christian group Joshua Project estimated there were are about 8 million Madurese in the early 2020s. [Source: Joshua Project; Wikipedia]

According to the 2010 census for Indonesia the total Madurese population was 7,179,356, at that time with 6,520,403 in Madura and East Java (East Java Province) ; 274,869 in West Kalimantan; 79,925 in Jakarta; 53,002 in South Kalimantan; 46,823 in East Kalimantan; 43,001 in West Java; 42,668 in Central Kalimantan and 29,864 in Bali. The 2000 census counted 6.8 million Madurese.

Official and academic data on the population of Madurese varies quite a bit. In the 1990s, it was said that as many 80 percent Madurese were dispersed from their home island of Madura. Some live in the nearby archipelagoes of Sapudi and Kangean, but nearly 8 million of the total 10.9 million at that time lived elsewhere. It was also said at that time that their numbers far exceeded the capacity of their island. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993 ~]

Over the centuries many Madurese have migrated to Java. A large number of them live in east Java and have given that region a bit of a Madurese character. More recently many have moved to Borneo and other islands as part of Indonesia's transmigration program. Between 1960 and 2000, more than 100,000 Madurese resettled in Kalimantan in Borneo from their home island of Madura. The local people quickly grew tired of them as they took away business and jobs. They often ran the shops and worked in the factories in the areas they migrated to.

Madurese Religion and Islam

Most Madurese are Sunni Muslims of the Shafi school (though a small number are Christians). Islamic was first introduced with the conversion of the petty kingdom of Arosbaya in 1528.

Islam lies at the heart of Madurese life. Madurese Muslims observe the five daily prayers, give zakat (alms), fast during the month of Ramadan, and celebrate major Islamic festivals such as Maulud (the Prophet’s birthday) and Id al-Fitr, when families also visit the graves of deceased relatives. Performing the pilgrimage to Mecca confers considerable social prestige. Modern reformist movements such as Muhammadiyah, which emphasize strict adherence to the Qur’an and reject ancestor worship, have found limited support outside major urban centers. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

As a group, the Madurese take pride in practicing what they see as a more orthodox form of Islam than their Javanese neighbors, many of whom retain ritual elements rooted in older animist and Hindu-Buddhist traditions. Pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) and tarekat (Sufi brotherhoods) occupy a central place in Madurese religious life. Kyai, respected religious scholars, often combine reformist teachings with roles as traditional healers and spiritual authorities.

At the same time, Madurese religion is deeply syncretic. Belief in ancestral spirits, ghosts, and other supernatural beings remains widespread. Offerings and ritual feasts are prepared to seek protection, ensure village welfare and good harvests, mark Islamic festivals, and secure success in activities such as trading journeys or bull races. Communal sacred meals known as kenduri are held at key life transitions and to attract good fortune.

Kenduri, comparable to the Javanese slametan, center on large cone-shaped rice dishes dedicated to both Allah and the ancestors. Only men participate directly in the feast, though portions are taken home for wives and children. Other rituals include ceremonies to request rain, annual rites honoring the spirits of springs and wells, and observances venerating sacred weapons such as kris and spears, often accompanied by ritual chanting known as gumbek. Bullfights and bull races—events for which the Madurese are well known—are likewise infused with beliefs in magic and sorcery used to gain advantage over rivals.

Madurese Development and Education

The average Human Development Index (HDI) for the four regencies of Madura in 2005 was 59.25. This is far below the HDI for Indonesia as a whole (69.6) and East Java (68.5). Pamekasan's GDP per capita was US$2,065, less than a third of East Java's (US$7,046). Sampang's Human Poverty Index was 38.3, almost twice East Java's (21.7). Sampang's infant mortality rate in 2000 was 89.55 deaths per 1,000 live births, which is almost twice the rate in East Java as a whole (47.69) and four times the rate in Jakarta. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The level of literacy on Madura is low by Indonesian national standards. The average literacy rate for the four regencies in 2005 was 76.2 percent considerably lower than East Java's rate of 85.8 percent In Sampang, one out of every three people was illiterate, which is a higher proportion than in Papua province, where 28.42 percent of the population was illiterate. According to figures from the 1990s, 88.2 percent of Madurese children attended elementary school, which is lower than in southern East Java, where the Madurese-speaking population is smaller. See also the article entitled "Indonesians." ^

Madurese Work and Economic Activity

The climate and soils of Madura are not compatible with high yield agriculture, especially wet rice cultivation. As a result the Madurese have traditionally emphasized livestock production and raised cattle, sheep and goats, some of which were exported to Java. Population pressure has led to very small landholdings, pushing many people into trading, handicraft production, and fishing. Land ownership is individual, though villages typically reserve communal plots and land to support village heads. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Women have traditionally worked as traders and laborers of wealthy farmers; men as traders, handicraft producers and salaried workers. Fishermen have traditionally used outrigger canoes and nets. Madurese outrigger boats with triangular sails are widely used in coastal trade, especially for transporting timber from Kalimantan to factories in Surabaya.

Madura's main crops are non-irrigated, particularly maize. Because of Madura’s arid conditions, rice can usually be grown only once a year. Madura is also known for its fruits and medicinal plants, and in recent decades tobacco has become a key cash crop—about one-fifth of Indonesia’s tobacco fields are located there. Traditional exports have included lime and salt, produced by evaporating seawater in coastal pans.

Many Madurese supplement their livelihoods through migration. Seasonal labor on East Java plantations is common, as is small-scale trading in cattle, tobacco, fruit, and coconut palm sugar across the archipelago. In East Java’s cities, Madurese often work as roof-tile makers, sand shovellers, pedicab drivers, dockworkers, or street vendors selling specialties such as soto and sate. Some surplus labor from Madura has also been absorbed by factories in Bangkalan, which is being developed as an extension of the Surabaya industrial region.

Madurese Transmigration

Large-scale transmigration has been a defining feature of Madurese history. Poor agricultural conditions on Madura encouraged migration from the nineteenth century onward, first under Dutch rule and later under the Indonesian state. As a result, many Madurese were resettled in sparsely populated regions—especially Kalimantan—and today more than half of all Madurese live outside their ancestral island, often maintaining a strong Madurese identity. [Source: Wikipedia]

On Java, where Madurese communities have existed for centuries, relations with the Javanese have generally been harmonious. Cultural exchange is common, intermarriage is widespread, and mixed pendalungan communities have emerged that blend Madurese and Javanese traditions.

In Kalimantan, however, transmigration sometimes led to serious conflict with indigenous Dayak populations, fueled by economic competition, cultural differences, and religious divisions. These tensions erupted into major episodes of violence in the late 1990s and early 2000s—most notably the Sambas (1999) and Sampit (2001) conflicts—resulting in thousands of deaths and the displacement of tens of thousands of Madurese. By the mid-2000s, conditions had largely stabilized, allowing many displaced Madurese to return to Kalimantan.

See Separate Article: TRANSMIGRATION IN INDONESIA: HISTORY, SETTLERS, PROBLEMS factsanddetails.com

Hostility Toward Madurese

The Madurese have long been viewed through stereotypes applied by their neighbors, especially the Javanese and Sundanese, and later reinforced by colonial and national governments, scholars, and the media. These portrayals depict Madurese as energetic, blunt, and less bound by etiquette, but also as hot-tempered and quick to defend their honor—often symbolized by the belief that Madurese men habitually carry weapons such as a kris, celurit (sickle), or machete. On the positive side, they are widely regarded as diligent and reliable workers, particularly in demanding manual labor. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Non-Madurese from all walks of life — teachers, merchants, civil servants and tourist guides — have traditionally despised the Madurese. After deadly attacks on Madurese by Dayaks in Borneo, many sympathized with the attackers. One Chinese man told the Independent, "They can not peacefully live along side other. Madurese just love to fight and steal." One man with a human ear strung around his neck like a pendent told the Independent, "We don't care about your race. We don't care about your religion. Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Dayak, Malay, Chinese or Bugi—all are welcome. We just don't want the Madurese. All of the Madurese must leave."

The Dayaks and Malays in Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo resent the Madurese’s economic aggressiveness and their insensitivity to the customs of other ethnic groups, seeming to look down on them. In the 1990s in much of west Kalimantan the Madurese monopolized the minibus transport system, expanded farming into disputed lands and managed to make more money than other ethnic groups. Other ethnic groups accused them of thugish behavior and stealing land. A 49-year-old Dayak schoolteacher old Time, "It's true we killed Madurese—and ate them. But we regarded them as animals. The Madurese are bad. They are thieves, killers, cheats. They take your coconuts, steal your chickens. It's impossible to live with the Madurese." The "unity in diversity" concept of Indonesia is "rubbish if the Madurese don’t respect or customs."

The trouble in Kalimantan has been blamed partly on deforestation and transmigration. Dayaks grew angry and frustrated as they were forced out of their forest homes and watched forestry jobs go to Madurese brought to Kalimantan as part of the Transmigration program not themselves.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025