SUNDANESE PEOPLE

The Sundanese hail from western Java but are found throughout Indonesia. Also known as the Orang Sunda, Urang Prijangan, Urang Sunda, they are culturally similar to the Javanese but regard themselves as less formal, more soft spoken and lighter hearted than Javanese. Sundanese make up 15.5 percent of the population of Indonesia and are the second largest ethnic group after the Javanese. They have their own distinct culture and speak their own language, which requires speaker to adjust their speech and vocabulary to accommodate the status and intimacy of the person they talk to. Nearly all are Muslims. The Sundanese homeland is the Priangan Highlands of West Java, an area they call “parahyangan” (“paradise”). [Source: David Straub,, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

The Sundanese (pronounced sun-duh-NEEZ) had their own state—the kingdom of Pajajaran (1333-1579)—but mostly they have been dominated by Javanese kingdoms while remaining somewhat isolated and keeping alive their own traditions. Islam was introduced by Indian traders in the 15th century and spread inland from the ports, where Indians traded. The nobility was forced to convert to Islam in1579 after the existing royal family was killed by the sultan of Bantem. The Dutch introduced coffee plantation agriculture. The Sundanese both cooperated with and resisted the Dutch. Some Sundanese pursued a Western education and became civil servants. Others fought two holy wars against the Dutch: one in the 1880s and another after World War II.

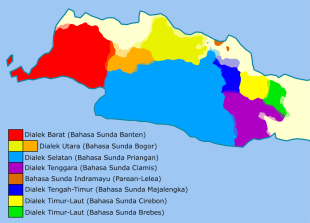

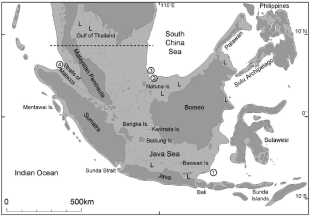

The homeland of the Sundanese — Sunda — is western Java (Jawa Barat) as far east as the Cipamali river. The name "Sunda" comes from Sanskrit, meaning "shining" or "pure," reflecting a connection to ancient kingdoms like Tarumanagara some sources say. Other sources say Sundal comes from an ancient volcano, Mount Sunda, that appeared in early geographical texts (Ptolemy, A.D. 150). Sundaland is a vast, sunken landmass in Southeast Asia that connected Borneo, Java, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula during glacial periods when sea levels were lower, creating a large, exposed continental shelf. The Sundanese people are believed to have originated from or migrated across this ancestral Sundaland.

One thing that stands out in the history of the Sundanese is their association with other groups. The Sundanese have little characteristic history of their own. Ayip Rosidi argues that the Sundanese are difficult to define as a distinct people because they lack a clear, unified identity. Unlike the Javanese, they have played only a minor role in national history and leadership, and major events in West Java were rarely distinctly Sundanese in character. Although many Sundanese participated in twentieth-century events, their overall historical impact was limited, and Sundanese history has largely followed that of the Javanese. As a result, scholars struggle to define Sundanese character and contributions, and even Sundanese intellectuals are hesitant to do so. Rosidi suggests that the Sundanese may have been absorbed into modern Indonesian culture, though he leaves open the possibility of a future ethnic renewal and redefinition of Sundanese identity. [Source: Sunda.org]

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUNDANESE SOCIETY: FAMILY, MARRIAGE, GENDER factsanddetails.com

SUNDANESE LIFE: VILLAGES HOUSES, FOOD, WORK factsanddetails.com

SUNDANESE CULTURE: FOLKLORE, MUSIC, SHADOW PUPPETRY factsanddetails.com

West Java

West Java is also called Sunda and is the homeland the Sudanese. West Java in an Indonesian province covers 46,229 square kilometers (17,850 square miles) and stretches from the Sundai Strait in the west to the central part of the island. The province is home to about 47 million people, more than most countries in the world, and is primarily mountainous, with rich green valleys hugging lofty volcanic peaks, many of which surround the capital of the province, Bandung. A mountain range of smoldering volcanoes runs from east to west. Upon the misty foothills of this range lovely tea plantations and ancient kingdoms can be found. Along the coast are unspoiled beaches and wildlife preserves. The area receives quite a bit if rain and is very green and lush.

West Java is densely populated and includes a substantial rural population. In some big cities, like Bandung, the capital of West Java, other ethnic groups begin to dominate as well. About 50 million people make their home in West Java. Islam is very strong here. The climate is tropical. The wet season lasts from September to March and the dry season is from March to September. The mountains and plateaus are somewhat cooler than the lowlands.West Java’s tropical climate, with an average of about 125 rainy days each year, Java’s productive soil has helped make it one of the densely populated places on earth. The climate is tropical, with a dry season from March to September and a wet season from September to March. The mountains and plateaus are cooler than the lowlands.

See Separate Article: WEST JAVA: ANCIENT HISTORY, GUNUNG PADANG, SUNDANESE CULTURE factsanddetails.com

Sundanese Population

There are estimated 42,000,000 Sundanese. The 2010 census counted 41,359,454 of them with 36,183,087 in West Java; 6,724,227 in Banten; 1,423,576 in Jakarta; 901,087 in Lampung; 451,781 in Central Java and 180,018 in South Sumatra. There were about 34 million Sundanese in the 1990s. [Source: Wikipedia]

The 1990 census found that West Java had the greatest population of any province in Indonesia with 35.3 million people. In addition, the urban population stood at 34.51 percent. Despite their large numbers, the Sundanese are one of the least known people groups in the world. They are often confused with the Sudanese of Africa and their name has even been misspelled in encyclopedias. Some spell checks on computer programs also change it to Sudanese. [Source: Sunda.org]

As the administrative and economic hub of Indonesia’s vast archipelago, Java attracts heavy movement from other islands and from abroad. As a result, the Sundanese are long accustomed to living and working alongside diverse peoples, particularly in major urban centers such as Bandung and Cirebon, as well as in the metropolitan region surrounding the national capital, Jakarta. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Administratively, Java is divided into three provinces. Central and East Java are inhabited mainly by the larger Javanese ethnic group, while the Sundanese form the majority population in West Java. Covering about 43,177 square kilometers (16,670 square miles), West Java is densely populated and includes a substantial rural population.

Sundanese Versus Javanese

The Sundanese are regarded as more Islamic, earthy, egalitarian and direct than Central Javanese. Although there are many social, economic, and political similarities between the Javanese and Sundanese, differences abound. The Sundanese live principally in West Java, but their language is not intelligible to the Javanese. The more than 21 million Sundanese in 1992 had stronger ties to Islam than the Javanese, in terms of pesantren enrollment and religious affiliation. Although the Sundanese language, like Javanese, possesses elaborate speech levels, these forms of respect are infused with Islamic values, such as the traditional notion of hormat (respect — knowing and fulfilling one's proper position in society). Children are taught that the task of behaving with proper hormat is also a religious struggle — the triumph of akal (reason) over nafsu (desire). These dilemmas are spelled out in the pesantren, where children learn to memorize the Quran in Arabic. Through copious memorization and practice in correct pronunciation, children learn that reasonable behavior means verbal conformity with authority and subjective interpretation is a sign of inappropriate individualism. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Although Sundanese religious practices share some of the HinduBuddhist beliefs of their Javanese neighbors — for example, the animistic beliefs in spirits and the emphasis on right thinking and self-control as a way of controlling those spirits — Sundanese courtly traditions differ from those of the Javanese. The Sundanese language possesses an elaborate and sophisticated literature preserved in Indic scripts and in puppet dramas. These dramas use distinctive wooden dolls (wayang golek, as contrasted with the wayang kulit of the Javanese and Balinese), but Sundanese courts have aligned themselves more closely to universalistic tenets of Islam than have the elite classes of Central Java. *

Although Sundanese and Javanese possess similar family structures, economic patterns, and political systems, they feel some rivalry toward one another. As interregional migration increased in the 1980s and 1990s, the tendency to stereotype one another's adat in highly contrastive terms intensified, even as actual economic and social behavior were becoming increasingly interdependent. *

Early History of the Sundanese

The Sundanese are of Austronesian origin and are believed to have originated in Taiwan and migrated through the Philippines, reaching Java between 1500 and 1000 B.C. Another hypothesis argues that the Austronesian ancestors of the contemporary Sundanese people originally came from Sundaland. No one knows where the Sundanese. originally came from nor how they settled West Java. Probably in the early centuries after Christ, a small number of Sundanese tribal groups roamed the mountain jungles of West Java practicing a swidden (slash and burn) culture. All the earliest myths speak of the Sundanese being field workers rather than paddy farmers.

Sunda Wiwitan is a folk religion followed by some of the Sundanese people, including Baduy and Bantenese. According to its origin myth of the Sundanese people: the supreme divine being, Sang Hyang Kersa, created seven bataras (deities) at Sasaka Pusaka Buana, the sacred place on earth. The eldest, Batara Cikal, is regarded as the ancestor of the Kanekes, while the other deities ruled different parts of Sunda lands in West Java. Sundanese legend also preserves memories of deep antiquity. The story of Sangkuriang is linked to the prehistoric lake once occupying the Bandung Basin, suggesting very early human habitation in the region. Another well-known proverb and legend explains the creation of the Parahyangan highlands, portraying them as a divine realm formed when the gods smiled—an image that emphasizes both their sacred character and natural beauty. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sundanese history can be traced with confidence to the fifth century, when the Tarumanagara dynasty consolidated power and developed trade networks reaching as far as China. This was followed by a series of Sundanese kingdoms based in different parts of western Java. These polities eventually gave way to more than three centuries of Dutch colonial rule, during which Sundanese territories became major producers of export commodities such as spices, coffee, quinine, rubber, and tea. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

The oldest known Sundanese literary work is Caritha Parahyangan. It was written about 1000 A.D. and glorifies the Javanese king Sanjaya as a great warrior. Sanjaya was a follower of Shivaism so we know that the Hindu faith was strongly entrenched by A.D. 700. Oddly enough, about this time a second Indian religion, Buddhism, made a brief appearance on the scene. Shortly after the Shivaist temples were built on the Dieng plateau of Central Java, the magnificent Borobudur monument was constructed near Jogjakarta to the south. The Borobudur temple is the largest Buddhist monument ever built in the world. It is thought that Buddhism was the official religion of the Shailendra Kingdom in Central Java from 778-870. Hinduism never faltered in other parts of Java and continued strong until the 13th century. A rigid class structure developed in the societies. The Sanskrit influence was widespread in the languages of the Java peoples. The idea of divinity and kingship blurred so that they became indistinguishable. [Source: Sunda.org ***]

According to Bernard Vlekke, the noted historian, West Java was a backward section of Java as late as the 11th century. Great kingdoms had arisen in East and Central Java but little had changed among the Sundanese. Hindu influence, while definite, was never as strong among the Sundanese as it was among the Javanese. However, as insignificant as West Java was, it had a king at the time of Airlangga of East Java; about 1020 AD. But Sundanese kings came increasingly under the sway of the great Javanese kingdoms. Kertanegara (1268-92) was the Javanese king at the conclusion of the Indonesian Hindu period. After him, the kings of Majapahit ruled until 1478 but they were not significant after 1389. However, this Javanese influence continued and deepened the impact of Hinduism on the Sundanese. ***

In 1333, the kingdom of Pajajaran existed near modern day Bogor. It was subdued by the Javanese kingdom of Majapahit under the famous prime minister, Gadjah Mada. According to the romantic tale Kidung Sunda, the Sundanese princess was supposed to be married to Ayam Wuruk, king of Majapahit. However, Gadjah Mada opposed this marriage and after the Sundanese had gathered for the wedding, he changed the conditions. When the Sundanese king and nobles heard the princess would become only a concubine and there would be no wedding as promised, they fought against overwhelming odds until all were dead. Although enmity between the Sundanese and Javanese continued for many years after this episode (and may still continue), never-the-less the Javanese exercised influence on the Sundanese. ***

Until recently, the Pajajaran Kingdom was thought to be the oldest Sundanese kingdom. Even though it existed as late as 1482-1579, much of the activity of its nobles is shrouded in legend. Siliwangi, the Hindu king of Pajajaran, was overthrown by a plot between the Muslims of Banten, Ceribon, and Demak in league with his own cousin. With Siliwangi’s fall, Islam took control of much of West Java. A key factor in Islam’s success was the advance of the Demak Kingdom of East Java into West Java by 1540. From the east and west, Islam penetrated to the Priangan (central highlands) and encompassed all the Sundanese. ***

Introduction of Islam to the Sundanese

The fall of the Javanese kingdom of Majapahit in 1468 has been linked with intrigue in the royal family due to the fact that a royal son, Raden Patah, had converted to Islam. Raden Patah settled in Demak which became the first Islamic kingdom on Java. It reached the zenith of its power by 1540 and in its time subdued peoples as far away as West Java. Bernard Vlekke says Demak expanded towards West Java because Javanese politics had little interest in Islam. In the meantime Sunan Gunung Jati, a Javanese prince, sent his son Hasanudin from Cirebon to make extensive conversions among the Sundanese. [Source: Sunda.org ***]

In 1526, both Banten and Sunda Kelapa (Jakarta) were under the control of Sunan Gunung Jati who became the first sultan of Banten. This alignment of Cirebon with Demak brought much of West Java under the sway of Islam. “In the second quarter of the 16th century, all the northern coast of West Java was under the power of Islamic leaders and the populace had become Muslim” (Edi S. Ekadjati, Masyarakat Sunda dan Kebudayaannya. Jakarta: Girimukti Pasaka, 1984:93). Since population statistics of 1780 list about 260,000 people in West Java, we can assume the amount was much less in the 16th century. This shows that Islam entered when the Sundanese were a small tribe located primarily on the coasts and in the river basins like the Ciliwung, Citarum, and Cisadane Rivers. ***

As Islam came to the Sundanese, the five major pillars of the religion were emphasized but in many other areas of religious thought a syncretism developed with the original Sundanese world view. The Indonesian historian Soeroto believes that Islam was prepared for this in India. “Islam which first came to Indonesia contained many elements of Iranian and Indian philosophies. But it was precisely those components which made the way easy for Islam here” (Indonesia Ditengah-tengah Dunia dari Abad Keabad, Vol. 2, 1968:177-178). Scholars believe Islam accepted that the customs which benefit society should be retained. Thus Islam was mixed with many Hindu and original customs of the people. The marriage of these religious strains is commonly called “the religion of Java.” The subsequent mixture of Islam with multiple belief systems (most recently called aliran kebatinan) makes an accurate description of present day religion among the Sundanese very complex. ***

Sundanese Under the Dutch

By the time the Dutch arrived in Indonesia in 1596, Islam had become the dominant influence among the nobility and leadership levels of Javanese and Sundanese societies. Simply put, the Dutch warred with Islamic power centers for control of the island trade and this created an enmity that extended the Crusades conflict into the Indonesian arena. In 1641, they took Malacca from the Portuguese and gained control of the sea lanes. Dutch pressure on the kingdom of Mataram was such that they were able to wrest special economic rights to the highlands (Priangan) area of West Java. By 1652, large areas of West Java were their suppliers. This began 300 years of Dutch exploitation in West Java which only ended with the advent of World War II. [Source: Sunda.org ***]

Events of the 18th century present a litany of Dutch errors in the social, political and religious fields. All of the lowlands of West Java suffered under oppressive conditions imposed by local rulers. An example of this was the Banten area. In 1750, the people revolted against their sultanate which was controlled by an Arabian woman, “Ratu Sjarifa.” According to Ayip Rosidi, she was a tool of the Dutch. However, Vlekke holds that “Kiai Tapa,” the leader, was a Hindu and that the rebellion was directed more against Islamic leaders than Dutch colonialists. [It is difficult to reconstruct history from any source as each faction had self interests which colored the way events were recorded. During the first 200 years of the Dutch rule in Indonesia, few of the problems were linked to religion. This was because the Dutch did practically nothing to bring Christianity to the indigenous people. ***

In 1851, there were 786,000 Sundanese and 217 Europeans in West Java. In 30 years the population doubled and the Priangan became a focal point of trade goods with an accompanying influx of western businessmen and Asian (mostly Chinese) immigrants. At the beginning of the 19th century, it was estimated that seven/eighths of Java was covered with forests or fallow land. In 1815, all of Java and Madura had only five million inhabitants. That increased to 28 million by the end of the century and reached 108 million in 1990. Population growth among the Sundanese is probably the most important non religious factor in their history. ***

As more land was opened and new villages arose, Islam sent teachers along with the people so that Islam increased in influence in every habitat of the Sundanese. The Islamic teachers competed with the Dutch controlled Sundanese nobility for leadership among the people. By the end of the century, Islam was the acknowledged formal religion of the Sundanese. The strong spirit beliefs of many kinds were considered part of Islam. Christianity, which came to the Sundanese in the mid-century had little effect outside of the small Sundanese Christian enclaves.

Recent Sundanese History

Opposition to colonial rule later drew the Sundanese into a broader struggle with other subject peoples for an independent and unified Indonesia. Independence was proclaimed on 17 August 1945, after a short but harsh Japanese occupation during World War II. Not all Sundanese supported national unification, however. Some cooperated with the Dutch or with Islamic rebel movements in attempts to establish a separate Sundanese homeland. These efforts were crushed by Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, and by the late 1950s the proposed “Sunda-land” had been fully absorbed into Indonesia as the prosperous province of West Java. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In the decades that followed, rapid urbanization and industrialization—interrupted at times by civil unrest—profoundly reshaped Sundanese society. Much of this transformation occurred under the authoritarian rule of President Suharto (1967–1998), who promoted industrial growth, expanded communications, and pursued population control policies in West Java. Many Sundanese viewed these changes with skepticism, as economic gains were concentrated among a small elite while most people remained poor.

In May 1998, student-led protests against the government culminated in a deadly crackdown in Jakarta, sparking widespread riots and public outrage. Western Java, the Sundanese heartland, experienced some of the worst violence, and Suharto was ultimately forced to resign. His fall ushered in a multiparty parliamentary democracy and a period of far-reaching political reform. Over the past decade, new policies have allowed greater recognition of minority rights, including renewed support for the Sundanese language.

Sundanese Language and Names

Like most Indonesians, the majority of Sundanese are bilingual, speaking both their mother tongue, Sundanese, and the national language, Bahasa Indonesia. Sundanese is commonly used in intimate settings such as the home and among friends, while Bahasa Indonesia dominates public and official contexts. Both languages belong to the Austronesian language family. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Sundanese is highly varied, with numerous regional dialects that differ in vocabulary, pronunciation, and style. What unites these dialects is a shared system of speech levels that reflect social hierarchy. Different words and verb forms are used depending on the relative status of the speaker and the listener—for example, when addressing elders versus children. Even basic verbs, such as “to eat,” change according to who is performing the action. In everyday use, speakers generally rely on two, and sometimes three, levels, though older generations may still employ as many as four.

In writing, Sundanese today is mainly rendered in Latin script. However, in 2003 the West Java government officially endorsed the renewed use of the modern Sundanese script in daily life. This script, adapted from writing systems used between the 14th and 18th centuries, has become closely linked to efforts to revive and strengthen traditional Sundanese culture.

Sundanese naming practices vary greatly. Some people have only one name, while others have a first and last name. Although women do not legally change their names after marriage, they are often referred to as "Mrs. [husband's name]." In Sundanese culture it is common that a nickname or name given later are integrated as the first name. For example someone is born with the name Komariah, Gunawan or Suryana written in their birth certificate. Later they acquire nicknames such as Kokom for Komariah, Gugun or Wawan for Gunawan, and Yaya or Nana for Suryana; as the result the nickname become the first name thus creating rhyming names such as Kokom Komariah, Wawan Gunawan, and Nana Suryana. [Source: Wikipedia; “Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of World Cultures,” The Gale Group, Inc., 1999 /=]

Sundanese Religion

The vast majority of Sundanese are Sunni Muslims, though small numbers identify as Catholic or Protestant. Sundanese Islam incorporates many traditional beliefs in spirits and agricultural rituals. Over the last few decades there has been an effort to purify the religion and expunge these elements and give non-Muslim rituals Muslim names and contexts. [Source: David Straub, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, 1993) ~]

Religion among the Sundanese broadly parallels that of the Javanese but is marked by a somewhat stronger commitment to Islam, though not as intense as among groups such as the Madurese or Bugis. This stronger Islamic orientation has played an important role in Sundanese history. Early Sundanese beliefs are difficult to reconstruct, but clues come from ancient epic poems (wawacan) and from the Baduy, whose belief system, known as Sunda Wiwitan, preserves many pre-Islamic elements. Sunda Wiwitan is largely animistic, centered on taboos and the belief that spirits inhabit natural objects, influencing human well-being according to adherence to these rules. Hindu influence among the Sundanese, as among the Javanese, did not replace indigenous beliefs but blended with them, leaving traces such as Sanskrit terms, myths, and ritual practices. [Source: Sunda.org ***]

Hindu ideas appear to have spread through cultural and spiritual influence rather than conquest, merging with older ancestor worship and reinforcing ritual life, especially ceremonies surrounding death. These blended traditions—combining animism, Hindu concepts, and later Islam—have helped shape and stabilize Sundanese cultural forms. Magic, spirit beliefs, and taboos continue to play a significant role in Sundanese life, particularly in life-cycle rituals, reflecting the enduring integration of ancient belief systems into contemporary religious practice.

Funerals: At death, Sundanese custom calls for relatives and neighbors to assemble immediately at the home of the deceased, bringing contributions of rice and money to support the bereaved family. Women typically prepare food and ritual offerings, while men construct the coffin and prepare the grave. The body is washed with water infused with flowers, after which a religious leader, or kiai, recites prayers. The deceased is then carried in a funeral procession to the cemetery. Commemorative ritual gatherings are later held on the third, seventh, fortieth, one-hundredth, and one-thousandth days after death, both to honor the memory of the departed and to pray for the easing of their sins. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Sundanese Islam

Many Sundanese Muslims observe the five daily prayers, fast during the month of Ramadan, and undertake the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lifetime. In urban areas, mosques are found in nearly every neighborhood, and the call to prayer is broadcast daily over loudspeakers. Islam is thought to have reached Java in the early fourteenth century. As it spread, local Muslims incorporated elements of earlier belief systems, and many pre-Islamic practices persisted. Among the Sundanese, this is especially evident in rituals connected to rice cultivation, which retain influences from earlier Hindu traditions or from pre-Hindu indigenous culture. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

As anthropologist Jessica Glicken observed, Islam is a particularly visible and audible presence in the life of the Sundanese. She reported that "[t]he calls to the five daily prayers, broadcast over loudspeakers from each of the many mosques in the city [Bandung], punctuate each day. On Friday at noon, sarong-clad men and boys fill the streets on their way to the mosques to join the midday prayer known as the Juma'atan which provides the visible definition of the religious community (ummah) in the Sundanese community." She also emphasized the militant pride with which Islam is viewed in Sundanese areas. "As I traveled around the province in 1981, people would point with pride to areas of particular heavy military activity during the Darul Islam period." [Source: Library of Congress *]

It is not surprising that the Sunda region was an important site for the Muslim separatist Darul Islam rebellion that began in the 1948 and continued until 1962. The underlying causes of this rebellion have been a source of controversy, however. Political scientist Karl D. Jackson, trying to determine why men did or did not participate in the rebellion, argued that religious convictions were less of a factor than individual life histories. Men participated in the rebellion if they had personal allegiance to a religious or village leader who persuaded them to do so. *

A small minority of Sundanese adhere to Sunda Wiwitan or to Ahmadiyah. Sunda Wiwitan is regarded as an ancient belief system predating both Hinduism and Islam. It combines animistic traditions with belief in a single supreme deity, known by various names such as Sanghyang Kersa, Batara Tunggal, Batara Jagat, and Batara Seda Niskala. Followers venerate the sun and believe that spirits inhabit natural objects like stones and trees. Most of the roughly 3,000 practitioners live among the Badui of West Java. Because Sunda Wiwitan is not officially recognized by the Indonesian state, its adherents have faced obstacles in obtaining identity documents and registering marriages. ^^

Ahmadiyah, founded in late nineteenth-century India by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, is viewed as heretical by many Sunni Muslims because of its theological claims. The Indonesian government has also refused to recognize Ahmadiyah as an official religion, and its followers have experienced discrimination and violence. In 2007, for example, mosques and homes belonging to Ahmadiyah families in Manis Lor, West Java, were attacked and burned by extremist groups. In 2008, President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono signed a decree restricting Ahmadiyah religious activities, threatening adherents with arrest if they continued to practice openly. ^^

Spirts, Magic and Non-Islamic Elements of Sundanese Religion

One very important aspect of Sundanese religions is the dominance of pre-Islamic beliefs. They constitute the major focus of myth and ritual in the Sundanese life cycle ceremonies. These ceremonies of the tali paranti (customary law and traditions) have always been oriented primarily around worship of the goddess Dewi Sri (Nyi Pohaci Sanghiang Sri). Not as great as Dewi Sri but also an important spirit power is Nyi Ratu Loro Kidul. She is the queen of the south sea and is the patroness of all fishermen. Along the south coast of Java, people fear and appease this goddess to this day. Another example is Siliwangi. This is a spirit power which is a force in Sundanese life. He represents another territorial power in the cosmological structure of the Sundanese. [Source: Sunda.org ***]

In the worship of these deities, systems of magic spells also play a major part in dealing with various spirit powers. One such system is Ngaruat Batara Kala which was designed to elicit favor from the god Batara Kala in thousands of personal situations. People also call on numberless spirits which include those of deceased people as well as place spirits (jurig) of different kinds. Many graves, trees, mountains and other similar places are sacred to the people. At these spots, one may enlist supernatural powers to restore health, increase wealth, or enhance one’s life in some way. ***

To aid the people in their spiritual needs, there are practitioners of the magic arts called dukun. These shamans are active in healing or in mystic practices like numerology. They claim contact with supernatural forces which do their bidding. Some of these dukun will exercise black magic but most are considered beneficial to the Sundanese. From the cradle to the grave few important decisions are made without recourse to the dukun. Most people carry charms on their bodies and keep them in propitious places on their property. Some even practice magic spells independently of the dukun. Most of this activity lies in an area outside of Islam and is in opposition to Islam. But these people are still counted as Muslims. ***

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025