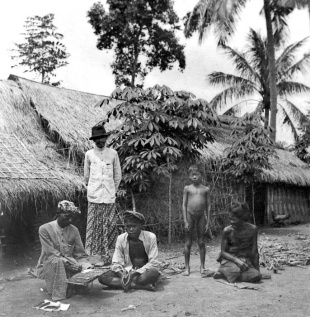

MADURESE SOCIETY

Among the Madurese both nuclear and extended families constitute the basic units of society. A distinction is made between kin (bhala) and all other people (oreng). Kinship is reckoned bilaterally along both paternal and maternal sides, although noble titles pass exclusively through the male line. The Madurese once had a noble class but it has largely disappeared. There are village leaders and religious leaders. The later often have more power and often preside over the education of children. Most Madurese belong to the Shafi school of Sunni Islam. They are regarded as more religious than Javanese. A number of traditional beliefs and customs remain such as communal sacred meals which are undertaken to bring good luck. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

In Madura’s former principalities, aristocratic descent granted a small segment of society claims to respect and obedience from commoners. In later periods, similar prestige came from positions in the colonial administration and, after independence, the national bureaucracy. Concentrated mainly in towns, this upper stratum of nobles and civil servants modeled its lifestyle on the Javanese priyayi elite, though with less emphasis on mystical practices, reflecting the generally orthodox Islamic orientation of Madurese society. Prosperous urban Madurese likewise tend to emulate the middle- and upper-class lifestyles of Jakarta. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

For rural communities, however, the most meaningful social distinction lies between “ordinary people” (golongan biasa) and the religious elite, known as golongan bhindara—the “children of the kyai.” This group includes religious scholars, their students (santri), village religious officials (modin), and others recognized for their Islamic knowledge (orang alim). Alongside these figures, villagers traditionally accord respect to local authorities such as the kelebun (village head), carek (village clerk), and apel (neighborhood head).

An important institution in Madurese social life is the aresan, a rotating savings gathering in which participants regularly contribute to a shared pot that is awarded by lot to one member at each meeting. Over time, every participant receives the pooled funds. Women often form their own aresan groups, known as diba’, which serve both economic and social purposes.

RELATED ARTICLES:

MADURESE: HISTORY, RELIGION, DEMOGRAPHICS factsanddetails.com

VIOLENCE AGAINST THE MADURESE IN BORNEO factsanddetails.com

EAST JAVA: SIGHTS, INTERESTING AND IMPORTANT PLACES factsanddetails.com

ETHNIC GROUPS ON JAVA factsanddetails.com

Madurese Family and Gender

Ideally, a newly married couple establishes its own household immediately; otherwise, it is common for the couple to live with the bride's parents initially. A daughter often takes care of the parents in old age and she inherits the house. Prior to their deaths, parents convey some of their property, including land and cattle, to their children. After their death, the children receive equal shares of the remaining property, which violates Islamic law. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Important ritual celebrations mark life passages such as the seventh month of pregnancy, a baby's first contact with the earth several months after birth, a boy's circumcision, and funerals and subsequent commemorative ceremonies. Girls sometimes celebrate their their first ear piercing. A family's honor depends heavily on the respectability of its women, which the men of the family will fight to defend. As a result, men may harass women traveling without a male escort (such as foreign female tourists). In the old kingdoms, a woman could not occupy the throne, but she could exercise de facto supreme power as the mother or guardian of the heir — particularly if she were the daughter of a former ruler.

The average Gender-Related Development Index for Madura's four regencies is 46.43 (2002 figures), which is dramatically lower than the figure for East Java as a whole (56.3). The Gender Empowerment Measure, which reflects women's participation and power in political and economic life relative to men's, is 35.9 for the four regencies, which is lower by an even greater proportion than the 54.9 for both East Java and Indonesia as a whole.

Madurese Marriage and Weddings

Madurese marriages have traditionally been between first or second cousins and have involved the payment of a bride price often in cattle. The marriage ceremony is Islamic but many Madurese customs have been incorporated into the wedding. Although polygamy is allowed by Islamic law it is rarely practiced. Marriage between cousins is believed to preserve the purity and continuity of the lineage. Strong kin solidarity is expressed through an extended family unit known as the koren, in which the descendants—often up to ten households—of a single great-grandfather live together within one compound. Polygyny has traditionally been limited to wealthy men or village officials who can afford it. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Marriage arrangements are initiated by the groom’s parents, who approach the bride’s family with a proposal accompanied by gifts. If the proposal is accepted, a bride-price—traditionally including cattle—is presented, and the groom’s family sets the wedding date. Although Madurese weddings follow local custom, a Muslim religious teacher (kiyai) presides over the religious aspects of the ceremony. In the event of divorce, marital property is divided by mutual agreement. Compared with neighboring Javanese and Sundanese communities, Madurese marriages are said to end in divorce less frequently.

In many respects, Madurese wedding customs resemble those of eastern Java, differing mainly in terminology. The process begins with nyalabar or ngembang nyamplong, when the groom’s family discreetly explores the possibility of a match. This is followed by narabas pagar, a formal inquiry to ensure that the woman has not already been promised to someone else. If she is free to marry, the groom’s parents formally request her hand by offering food and gifts—among wealthier families, these may include jewelry and batik cloth. Acceptance by the bride’s family, known as balee pagar, confirms the engagement. The groom’s family then delivers the bride-price in a stage called lamaran or saseraan, with cattle considered an essential component. Only after this exchange does the formal wedding ceremony (akad nikah), conducted by a Muslim religious official, take place.

Madurese Honor and Revenge

A strong sense of personal honor underpins much of Madurese social behavior. Men avoid attending events without explicit invitations, prefer to work their fields only with close family members, and insist on clearly defined terms before cooperating with others. Negotiations are commonly conducted through intermediaries, who also serve as witnesses to financial exchanges. This emphasis on dignity and self-respect helps explain the reserve—and occasional aloofness—many Madurese villagers display toward outsiders. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Madurese are regarded as hot tempered, aggressive, hostile and clannish and prone to turning to violence to settle disputes. Madurese women have a reputation for being excellent in bed, immoral, demanding and difficult to live with. Many Madurese say that their name comes from the combination of “madu” (“honey”) and “dara” (“girl”).

The Madurese are also regarded as proud and blunt. They exert strong control in the Surabay area of Java. The people of Surabay are regarded as more course and lacking in manners by the traditionalists of Central Java. The Javanese spoken there is considered vulgar. With all that said, the Madurese have traditionally been devout Muslims. Many regard them as hospitable as they are rough.

Madurese men are known for their brutal code of honor. They have traditionally carried big curved knives called “caroks”, which other people say they are ready to use at the slightest provocation. Men killing a rival have traditionally grabbed an enemy from behind and cut his carotid arteries or stomach. Such a punishment was inflicted on adulterers, cattle thieves, and people accused of dishonor and making face-losing insults. Carok attacks are often fatal and a single attack can trigger a blood feud that can endure for generations. Sometimes religion leaders are called on to intervene and head off a carok attack. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993]

Madurese Villages and Houses

The majority of Madurese on Madura live in small hamlets that function as administrative units rather than as settlements organized around kinship or older political structures. Each hamlet typically contains between five and fifteen household compounds, scattered across surrounding farmland. [Source: Daniel Strouthes, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Traditional Madurese houses are classified by both layout and roof type. Some consist of a single room—known as slodoran or malang are—while others have multiple rooms and are called sedanan. Roof designs also vary: the gadrim has a two-ridge roof; the sekodan is supported by four central pillars; and the pacenanan features gables carved in the form of serpents, reflecting Chinese artistic influence. These houses are usually windowless and oriented either north–south or toward the rising sun.

External influences have introduced additional features, such as a front porch used for sleeping and a rear porch for sitting and relaxation. Each household also maintains a dedicated space—either a room or a separate structure—for prayer. Until relatively recently, modern amenities were uncommon; in the 1990s, only a small minority of households had access to clean water or electricity compared with other parts of East Java.

Madurese villages generally lack a formal layout, with houses clustered amid open fields. In upland areas, one settlement type, the kampong meji, consists of about 20 households descended from a common ancestor over five generations. In Sumenep, another form known as tanean lanjeng features five houses facing a shared courtyard and occupied by relatives linked back to the third generation. Land ownership in Madura is primarily individual, although some village land is held communally to support the village head and his assistants.

Madurese Food and Clothes

Boiled rice mixed with ground maize forms the staple diet, typically accompanied by dried salted fish or side dishes of dried meat and vegetables, all flavored with chili sauces. Meals are usually followed with water or tea; since the colonial period, consumption of tuak (palm wine) has been discouraged. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Madura is known for a range of local specialties, including perkedel jagung (corn fritters often mixed with shrimp), la’ang (a regional drink), blaken (fish paste sold in traditional handmade jars), yam-based taffy, and fruits such as guava and salak, recognizable by its dark, scaly skin, pale tangy flesh, and large pit. Beyond the island, Madurese cuisine is especially famous for chicken dishes, soto (a savory soup), and sate—grilled goat-meat skewers dipped in sweet soy sauce and chili.

The sarong and “peci” are the garments of choice. Traditional dress reflects both function and symbolism. Women commonly wear a kebaya (a long-sleeved blouse) paired with a sarong that falls below the knees, along with bracelets and anklets (bingel). Men traditionally dress in dark-colored clothing that includes a distinctive headdress (destar), a horizontally striped undershirt—often red and white—a collarless long-sleeved outer shirt, knee-length trousers, and a wide sash tied at the waist. The colors black, red, yellow, white, green, and blue hold cultural significance and are frequently expressed in Madurese batik patterns.

Madurese Art, Entertainment and Martial Arts

Woodcarving is a highly developed art among the Madurese. This is evident in bull-racing gear and locally made furniture, such as beds, screens, chests, cupboards, and cake keepers, which show Chinese and European influences. Madurese batik cloth comes in rich, bold colors such as red, red-brown, and indigo, and features designs of winged serpents, sharks, airborne houses with fish tails, and other fantastical sea creatures. Women also wear large silver bracelets, and black coral bracelets are another regional specialty believed to prevent illness and cure rheumatism. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

Penca silat, an Indonesian martial art, is practiced in clubs and in competitions, though women only participate as amateurs. One sport that is now played in secret is ojung, in which men duel with rattan sticks. Training homing pigeons is also a popular pastime. ^^

Madurese literature is usually religious works such as the Qur'an, sung poetry, comic books, and legends (a source for drama plots). Compared to their urban counterparts, rural people listen more frequently to the radio, tuning in to regional and national music, especially dangdut and pop Indonesia, as well as cassettes of comedic performances. Villagers watch television at the village head's house or at food stalls called warungs, and they watch movies at outdoor cinemas and attend traditional performances sponsored by richer villagers. ^^

Madurese Music and Shadow Puppetry

The Madurese have their own form of shadow puppetry — wayang topeng. Drawing on stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, its resembles Javanese shadow theater in that a single performer acts as narrator, director, and musical conductor, voicing all the parts. Instead of puppets, however, the roles are performed by masked dancers or actors. Although often regarded as the quintessential symbol of Madurese culture, wayang topeng has declined in popularity. Far more vibrant today is loddrok, a more down-to-earth dramatic form in which unmasked actors speak their own lines and sing Madurese songs (kejhung). Loddrok frequently replaces wayang topeng at village ceremonies. Another popular theatrical genre blends Islamic (Arab–Persian) stories with Indian dance elements; these performances include women and professional transvestite performers and charge admission. [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ^^]

The Madurese also maintain gamelan orchestras similar to those of Java, though the instruments are more often made of iron rather than bronze. The principal singer is frequently a female impersonator rather than a woman. Gamelan music accompanies wayang topeng, loddrok, and tayub, a dance in which a single female performer dances for a male audience and invites individual men to join her. Another refined art form is mamaca or macapat, where one performer sings poetic texts in Javanese while another translates them into Madurese; this tradition survives in old palaces, village rituals, and aresan gatherings.

Many village events, including bull contests, are accompanied by the kenong telo ensemble, which features drums, gongs of various sizes, metal rattles, and the distinctive saronen, a piercing oboe-like instrument. Alternative ensembles include bak beng, using bamboo instruments, and ngik-ngok, which combines a violin with modified brass instruments. During Ramadan nights, village youths roam the streets playing wooden slit gongs known as tuk-tuk or tong-tong.

More orthodox Muslims often criticize traditional music and theater, associating them with idolatry, sacred-tomb veneration (bhuju’), or the perceived moral excesses of wayang topeng and loddrok. By contrast, some performance genres enjoy greater religious respectability because of their Middle Eastern roots. Haddrah consists of male group singing that incorporates Madurese songs and martial-arts movements, while samman, introduced from Yemen via Aceh in 1902, is performed in mosques by men who chant and dance in formation with rising waves of intensity.

Madurese Bull Racing

The Madurese love their cattle. Bull fights and bull races (“kerapan sapi”) are big events. In bull races, riders stand on a wheel-less device yoked to two oxen supposed to replicate a plow. The devise looks like a cross made from poles. The legs of the riders are secured onto the vehicle like feet inside ski boots. They propel the oxen forward by yanking on their tails. Contestants often employ sorcery and magic in an effort to defeat their rivals.

There are bull racing stadiums all over Madura. The biggest one is in Pamekasan, Madura’s capital. The bulls are carefully bred and prize bulls are quite valuable. When they are young they are pampered and given various things—including beer, raw eggs, special herbs and honey—to help them grow up strong and fast.

Bull Races and trials are held throughout the year, including shows for tourists, with the serious racing beginning in August. The competition gets especially lively in September and October, during the dry season (September–October), when the quarterfinal action begins. The final is held in Pamekasaan the capital of Madura. The final races may feature as many as 100 bulls. They are decorated with flowers, ribbons and ornamental harnesses and led in a procession through the town. During each race two pairs of oxen are pitted against one another. Gamelan music is played before the race to get the bulls excited. Just before they are set loose they are given healthy helpings of arrack.

They races are 100 meters with the fastest times being around 10 seconds. The cattle don’t always run in a straight line. The bulls reach speeds of 36 kilometers (22 miles) per hour. Occasionally they charge into the crowds. The winners get prize money and earn bigger money from stud fees.

Only village leaders and wealthy farmers can afford to maintain a bull-racing team, which includes a skilled jockey, bull masseurs, and other personnel. Not to mention, the bulls are of the best breed and, unlike draft oxen, are pastured daily. Elaborately carved wooden yokes painted in bright red and gold and other racing equipment are often passed down as family heirlooms. Winning a bull race, especially the island championship, is an intensely coveted honor. Competitors resort to spying or black magic to gain an advantage over their opponents. A full contingent of police is present at the races to suppress any outbreaks of violence." [Source: A. J. Abalahin, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In the days leading up to a race, specialists feed the bulls a special diet of fresh grass, eggs, coffee, and herbal potions. The preceding night, the racing team holds an all-night vigil accompanied by continual gamelan music. Before the race, the Tari Pecut dance is performed, depicting the steps involved in caring for racing bulls.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025