BADUY

The Baduy are one of the most unusual groups in Indonesia. Nobody really knows anything about them. Their villages are closed to outsiders especially during their sacred rituals. Practically the only thing they eat is rice and they seem to spend most of their time communicating with spirits. They are throught to have retreated to the mountains when Islam came to their homeland and they fled there to keep their religious customs alive. Generals and politicians sometimes seek them out for their perceived ability to see into the future. [Source: Harvey Arden, National Geographic, March 1981]

Ed Davies of Reuters wrote: “Despite their proximity to the Indonesian capital, the Baduy might as well be a world away as they live in almost complete seclusion, observing customs that forbid using soap, riding vehicles and even wearing shoes. Within a 50 square kilometers (20 square mile) area in the shadow of Mount Kendeng, the Baduy people cling to their reclusive way of life despite the temptations of the modern world. No one is certain of their origin. Some anthropologists think they are the priestly descendents of the West Java Hindu kingdom of Pajajaran and took refuge in the limestone hills where they now live after resisting conversion to Islam in the 16th century. They speak an archaic version of Sundanese, a language spoken by many in this part of western Java.” [Source: Ed Davies, Reuters, November 27, 2008]

The Baduy (also spelled Badui) call themselves Urang Kanekes—urang meaning “people” in Sundanese and Kanekes referring to their sacred homeland. They live in the western part of Indonesia’s Banten Province, near Rangkasbitung. Estimates of their population range from about 5,000 to 11,700, depending on how they are counted. Most Baduy communities are concentrated in the Kendeng Mountains at elevations of 300–500 meters above sea level. Their homeland covers roughly 50 square kilometers of hilly forest, about 120 kilometers from Jakarta. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ethnically, the Baduy belong to the Sundanese people. Physically, linguistically, and racially they closely resemble other Sundanese, but they differ sharply in lifestyle. While most modern Sundanese are Muslims and relatively open to outside influences, the Baduy consciously resist foreign contact and strictly preserve an ancient way of life. They speak a dialect derived from archaic Sundanese, although traces of modern Sundanese and Javanese can be heard. The Baduy are divided into two groups: the Baduy Dalam (Inner Baduy) and the Baduy Luar (Outer Baduy). Outsiders are not permitted to meet the Inner Baduy, whereas the Outer Baduy maintain limited contact with the outside world. The origin of the name “Baduy” is uncertain; some suggest it derives from the word “Bedouin,” while others argue it comes from the name of a local river.

One theory holds that the Baduy descend from the aristocracy of the Sunda Kingdom of Pajajaran, who once lived near Batutulis in the hills around Bogor, though there is little firm evidence to support this claim. Their domestic architecture, however, closely follows traditional Sundanese forms. The port of Sunda Kelapa—associated with Pajajaran’s capital at Dayeuh Pakuan—was destroyed in 1579 by Muslim forces led by Fatahillah, and Dayeuh Pakuan itself was later conquered by the Banten Sultanate. Another theory suggests that the Baduy originated in northern Banten, where pockets of people still speak the same archaic Sundanese dialect used by the Baduy today.

Baduy Religion and Taboos

The Baduy blend ancient Hindu elements with animism, believing their homeland—Pancer Bumi—to be the center of the world. They see themselves as the first people on earth, bound by strict rules intended to prevent cosmic disaster. Renowned for their mystical authority, Baduy leaders known as pu’un conduct rituals at a secret site called Arca Domas, a megalithic sanctuary where ancestral spirits and gods are appeased. Although their way of life may appear primitive on the surface, researchers note that the Baduy are highly attuned to their environment. For example, the prohibition on metal hoes helps limit soil erosion when cultivating dry rice. Still, their many taboos often seem to make daily life exceptionally demanding. Formal schooling is forbidden, as are glass, alcohol, nails, footwear, diverting watercourses, and raising four-legged animals. As anthropologist Boedhihartono of the University of Indonesia observed, “There is no education. Going to the field is an education for them.” [Source: Ed Davies, Reuters, November 27, 2008]

The Baduy religion is known as Sunda Wiwitan, a system that combines traditional beliefs with Hindu influences. Because of their long isolation, however, their faith is closer to animism—particularly ancestral spirit veneration—than to formal Hinduism or Buddhism. Hindu-Buddhist influences remain visible in ritual practices and terminology, and over time limited Islamic elements have also been incorporated. According to kokolot (elders) in Cikeusik village, the Kanekes people do not follow Hinduism or Buddhism as organized religions; rather, they practice animism shaped by later Hindu and, to a lesser extent, Islamic ideas. [Source: Wikipedia]

In recent years, some Islamic influence has also appeared among a few Baduy Luar communities, especially in Cicakal Girang village, often blended with local interpretations. Ultimate spiritual authority rests with Gusti Nu Maha Suci, who, according to Baduy belief, sent Adam into the world to live as a Baduy.

Baduy life is governed by extensive mystical taboos. They are forbidden to kill, steal, lie, commit adultery, become intoxicated, eat at night, use vehicles, wear flowers or perfume, accept gold or silver, handle money, or cut their hair. Additional prohibitions relate to protecting their land: they may not grow wet rice (sawah), use fertilizers, cultivate cash crops, employ modern farming tools, or keep large domestic animals. While Hindu influences are evident, the core of Baduy belief remains a deeply rooted animism centered on ancestral veneration, developed centuries before sustained contact with Islamic, European, or other foreign traditions.

Baduy Society

Generally, the Baduy are divided into two main groups: the Baduy Dalam (Inner Baduy) and the Baduy Luar (Outer Baduy). The clusters of villages in which they live are regarded as mandalas—a term derived from Hindu–Buddhist thought but used in the Indonesian context to describe places where religious life is paramount and shapes all aspects of daily existence. [Source: Wikipedia]

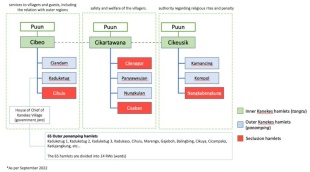

The Baduy Dalam number about 400 people, comprising roughly 40 kajeroan families. They live in three villages—Cibeo, Cikertawana, and Cikeusik—within Tanah Larangan, the “forbidden territory,” where outsiders are not permitted to stay overnight. Considered the most conservative and “pure” Baduy, the Dalam observe the buyut system of taboos with exceptional strictness and maintain minimal contact with the outside world. They are often described as the people of the sacred inner circle. Only the Baduy Dalam have pu’un, the highest spiritual leaders of Baduy society. The pu’un alone are allowed to enter the most sacred site on Gunung Kendeng, known as Arca Domas. In contrast to the Outer Baduy, the Dalam show little to no Islamic influence.

The Baduy Luar make up the majority of the Baduy population. They live in 22 villages surrounding the Inner Baduy settlements and serve as a buffer between the sacred core and the outside world. Although they also follow the taboo system, they do so less rigidly and are more open to limited modern influences. Some Baduy Luar now wear the colorful sarongs and shirts favored by neighboring Sundanese communities, a change from the past when they were restricted to homespun blue-black cloth and forbidden to wear trousers. Items such as toys, money, and batteries have increasingly entered Outer Baduy villages, especially in the north. Travel beyond their homeland is no longer unusual: some Baduy Luar journey to Jakarta or work seasonally as hired laborers during rice planting and harvests, while others find employment in cities such as Jakarta, Bogor, and Bandung. In a few outer villages, animal meat is eaten and dogs are trained for hunting, although raising livestock remains prohibited.

Formal schooling for Baduy children runs counter to traditional custom. The community has consistently rejected government proposals to build schools in their villages. Even during efforts under the government of Suharto to impose modern education and social change, the Baduy strongly resisted. As a result, only a small number of Baduy are able to read or write.

Baduy Isolation

Baduy society is organized into two distinct zones: an outer ring of villages and an inner heartland consisting of just three settlements. Those who violate Baduy rules are expelled from the inner heartland and resettled in the outer zone. The inner community—about 800 people, or roughly 40 families—wears white clothing, in contrast to the dark attire of the outer villages, and observes Baduy traditions with far greater rigor.Reaching Baduy territory requires demanding treks along slippery paths that wind through steep valleys. Foreign visitors are permitted to enter the outer zone, but only for a few nights, sleeping on bamboo mats in villages that are completely dark after sunset due to the absence of electricity. Access to the sacred inner villages is, in practice, almost impossible for non-Indonesians. High in the lush hills of far western Java, the Baduy maintain a largely peaceful existence, relatively untouched by the modern world. [Source: Ed Davies, Reuters, November 27, 2008]

The outer villages function as a buffer zone. Leaders from the inner Baduy occasionally make unannounced visits to ensure that outer communities are not violating too many taboos, sometimes confiscating items such as radios that are considered pollutants from the modern world. Without motorbikes or smoke-belching buses, Baduy villages are notably quiet; the gentle clatter of weaving looms is often one of the few sounds that break the silence.

Baduy depend on carefully controlled interaction with outsiders to preserve their traditions and resist Islamization. Their deliberate secrecy and reluctance to engage with foreigners help sustain their reputation for possessing supernatural powers—an image they actively reinforce. How long the Baduy have lived in seclusion remains uncertain, and little is known about their early cultural history, aside from the clear presence of Hindu and Buddhist elements in their religion. Local legends place their origins in the 16th century, after the fall of the Sunda Kingdom of Pajajaran to Muslim conquerors. According to these stories, the Baduy resisted Islam, were defeated, and withdrew into the mountains where they live today. [Source: Brigitte Cavanagh, Cultural Survival Quarterly, Summer 1983]

During Dutch colonial rule in 1931, the Baduy narrowly avoided forced relocation. Colonial officials viewed their slash-and-burn agriculture as a threat to Banten’s forests and downstream irrigation systems. However, after visiting Kanekes, Dr. Mulhenfeld, then head of the colonial Interior Department, rejected the proposal, concluding that removal would destroy Baduy culture. In independent Indonesia, the Baduy have continued to defend their cultural heritage despite government efforts to integrate them into wider society, including pressures to convert to Islam. They refuse to see themselves as passive victims of change, believing instead that they have a sacred duty to preserve cosmic harmony—a balance they see as inseparable from the survival of their culture.

How the Baduy Maintain Their Isolation and Deal with Outsiders

Brigitte Cavanagh wrote in Cultural Survival Quarterly, “To ensure protection, Badui society is divided into two groups. The inner Badui, or holy members of the hierarchy, occupy three sacred villages in the Taneh Larangan or "Forbidden Territory". They protect their community from exposure to external influences in order to ensure purity. Various buyut (tabu) impose seclusion upon them and prohibit the import of any form of technology (except knife blades). The holy members also discourage outsiders from gaining access to their community. / [Source: Brigitte Cavanagh, Cultural Survival Quarterly, Summer 1983 /]

“The Panamping, or outer Badui, live in some 28 villages and represent the commoners and the majority of the population of Kanekes. Their villages are located on the border between the Forbidden Territory and the Sundanese settlements. Due to the scarcity of land owned by the Badui they depend economically on the Moslem Sundanese. Although the seclusion has lessened, due to intermingling with the Sundanese community, the outer Badui continue to be hostile to non-Badui visitors. Geographically and politically their settlement is sheltered by the presence of the Moslem community, whose chiefs act as intermediaries between the outer Badui and non-Badui. Formal relations with the government and foreigners in general, are administered by a Jaro dangkas, a Badui hereditary chief who acts as a mediator by controlling direct communication with the Pu'un, supreme chief of the entire Badui society. /

“While outsiders are forbidden to approach inner Badui land, the Pu'un sends a delegation to a non-Badui city, Serang, the capital of Banten, annually. Fruits from the sacred land are ritually offered to the local administrator to symbolize the bond between the contemporary Sundanese and the supernatural guardians of the Sundanese soil and tradition.” /

Baduy Secret Rituals

Brigitte Cavanagh wrote in Cultural Survival Quarterly, “Each of the three sacred villages is presided by a Pu'un whose superiority, according to the Badui cosmogony, is based on his sacred descent. The Pu'un are religious and political figures renowned for their supernatural power, inside and outside Kanekes. A Pu'un can read minds, predict the future and influence fortune. The supreme Pu'un represents the 13th generation of Batara Tungall, the upper deity of the Badui. [Source: Brigitte Cavanagh, Cultural Survival Quarterly, Summer 1983 /]

“Traditionally, the Pu'un have been forbidden to divulge the secrets of the Badui people's rites and customs. Only a few anthropologists have succeeded in gathering second-hand data. What has been disclosed is contradictory, reflecting the effectiveness of their controlled communication. More than anything else, the Badui want to be left in peace and are suspicious when questioned by outsiders. /

“No outsider has ever been allowed to witness the rituals performed at Area Domas, the sacred place of worship restricted to the Pu'un and other high officials. Area Domas is where the soul of the Badui reunites with Batara Bungall after death. Every year the Pu'un brings back from Arca Domas predictions which shape the destiny of the community. The Badui claim that mysterious forces exist in Arca Domas, and that any intrusion or disturbance in the sacred place of worship would adversely affect prosperity in the world. Although the supernatural power of the Pu'un is accepted as omnipresent, there have been instances when, unaware, he allowed himself to be seen by visitors.

Baduy Fortunetelling and Clairvoyance

Brigitte Cavanagh wrote in Cultural Survival Quarterly, “Many Sundanese still consider the Badui their guide for moral conduct and law. To the Javanese, the Badui are predominantly associated with magical power. The fascination of the Javanese with the Badui's mystical power strengthens the powerful image projected by the Pu'un. As a spiritual leader, a Pu'un will see Indonesian citizens who seek his guidance, but generally one must be recommended by an influential person from outside Kanekes. Visitors are then escorted to the lowest ranking village and are not allowed to stay after consultation. [Source: Brigitte Cavanagh, Cultural Survival Quarterly, Summer 1983 /]

“Until the 1960s even the leaders of Indonesia valued consultation with the Badui. Under Sukarno, the former President of Indonesia, Badui were given government protection, even the President visited the Pu'un by helicopter on several occasions. He was given a Kris by the Badui when he came to power, perhaps to symbolize the link between the mythical founders of Java and the current generation of the Indonesian people. /

“Even today many government officials and politicians believe they owe their positions to the Pu'un's power. Yet in spite of the widespread respect for the Pu'un, the survival of Badui tradition is threatened. Recently, there has been government pressure to send Badui children to school. Schooling and Islamic teachings are a means of gradually integrating Badui society into the larger Islamic society of Indonesia.” /

Efforts to Modernize the Baduy

Ed Davies of Reuters wrote: “Although generally left to their own devices by colonizers ranging from the Dutch to the Japanese, authorities have at times sought to include the Baduy in mainstream society. When the government of Indonesia's long-time strongman president Suharto tried to foist development on the Baduy in the 1980s they sent an emissary to plead to be left alone. Suharto, a deeply superstitious man with a weakness for Javanese mysticism, conceded and arranged for the Baduy to mark out their territory with poles to protect them from outside influence. [Source: Ed Davies, Reuters, November 27, 2008]

Brigitte Cavanagh wrote in Cultural Survival Quarterly, “A Javanese anthropologist wearing the slogan "to research, to teach, to serve" on his T-shirt, explained that people like the Badui should be forced to "progress." He added that it was nevertheless very difficult to enter Kanekes because they (the Badui) are "very strong." When relations with the government are at stake, the Badui turn from mysticism to shrewdness and pragmatism. The Badui do not resort to violence to solve their difficulties, instead they warn that any disruption within their society would lead to disturbance in the cosmos. How long can such a defense be effective? [Source: Brigitte Cavanagh, Cultural Survival Quarterly, Summer 1983 /]

“The Badui strive to keep one step ahead of the government. An ethnomusicologist and scholar of the Badui reported that to alleviate government pressure, the Badui built a symbolic mosque on their territory. When a population census was being taken, the Badui already had their answers available. Although I was given the figure of 5,000 for the whole of Kenekes, the actual number of their population is kept secret. Aware of the threats to their culture, ten years ago the Pu'un requested a Dutch scholar in Java to record their history. Much to this scholar's surprise, two Badui dressed in white - the traditional color of the inner Badui - arrived in his office. He had never been in contact with the Badui before, and to this day he wonders why they chose to trust him and how they found him. /

“Despite several cultural changes that other people in Java have experienced throughout the centuries, the Badui have maintained their ancient tradition. Now their future is their major concern. If the government is successful in establishing its educational system, Badui culture will be destroyed. Already, the outer Badui have frequent contact with the outside world. As a result some of them are confused about their identity. The development project of the government is not committed to the welfare of Badui society, but rather is motivated by ideological reasons based on Islam and notions of centralized states. The Badui will not benefit from assimilation into Islam, nor will they gain materially. Java is well known as one of the world's poorest and most densely populated regions (80 million people eking out a living on an island the size of New York State). The present religious, economic and political system in Java cannot offer them a significantly better existence than the one they have established in Kanekes.” 8/8

Baduy Immune to Global Economic Crisis But Money and TV Seep In

In 2008, in the midst of the Lehman Brothers global economic crisis, Ed Davies of Reuters wrote: “ High in the lush hills of far western Java" the Baduy "tribe lives a peaceful existence, untouched by the turmoil of the financial crisis. Villagers stare blankly when asked about events in the outside world. Salina, a young mother, plays with her son on the steps of a thatched-roof hut in this small river-side village. "I don't understand about any crisis," she says when asked about the economic turmoil that has taken its toll on the rupiah which has lost almost 25 percent of its value this year.[Source: Ed Davies, Reuters, November 27, 2008 |::|]

“But it is difficult to keep all things at bay from the modern world. On a recent trip some Baduy children had forsaken traditional wear, one wearing a blue Italian soccer shirt, while the use of formally taboo money has replaced bartering with the outside world. The outer Baduy sell sarongs they make and also travel to nearby towns to sell honey and palm sugar. The cash is used to buy salted fish and other things they can't produce themselves. "Even in the center they already know money," said anthropologist Boedhihartono, who has over years developed what he describes as "a sort of friendship" with the Baduy. He keeps a room free at his Jakarta home for when the Baduy sometimes make unannounced visits after a three-day bare-foot trek since they are not allowed to use transport. |::|

“Asked about whether they had much knowledge of the outside world, he said: "Of course not really, except if they come to my house they watch the TV." While the Baduy are supposed to shun modern medicine, he said the use of antibiotics had helped sharply increase their numbers. The main threats they faced, he said, are from outsiders trying to plunder their land and proselytizing by some groups in the majority Muslim community surrounding them. The Baduy have taken on some outside influences such as circumcision, which is in line with local Muslim practices. |::|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East / Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993; National Geographic; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025