INDONESIAN ELECTION IN JUNE, 1999

Indonesia held its first true free elections in 44 years in June 1999 when 468 of the 500 seats in the House of Representatives (DPR) were up for grabs (the other 38 were served for the military). A total of 10,500 candidates from 48 parties took part. The voting was done in one day but the counting was done by hand and took almost two months to complete.

After Suharto stepped down there was a lot of discussion about which direction the political system would go. Thirteen months after Suharto resigned and Habibie became president it was decided to hold elections ahead of the usual five-year cycle (it had only been two years since the last one in 1997). Things were speeded up due to the public demand for a new legitimate government and leadership.

The June 1999 voting was carried out at 250,000 polling station manned by 500,000 election monitors, including Jimmy Carter and 500 others from outside Indonesia. Voters stuck a pin through a piece of paper with the symbol of each party on it. There were reports of sporadic violence and some allegations of vote-rigging but over all the voting seemed fair and free.

RELATED ARTICLES:

REFORMASI AND THE POST–SUHARTO ERA factsanddetails.com

B.J. HABIBIE (PRESIDENT OF INDONESIA 1998-1999) factsanddetails.com

MEGAWATI SUKARNOPURTI (PRESIDENT OF INDONESIA 2001-2004): LIFE, POLITICAL CAREER, FAILURES factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER SUHARTO: NEW ORDER, DEVELOPMENT, FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

CORRUPTION AND FAMILY WEALTH UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

1997-98 ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

OUSTER OF SUHARTO IN 1998: PRESSURES, EVENTS, RESIGNATION factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO AFTER HIS RESIGNATION: TRIALS, DEATH, LEGACY, VIEWS, FAMILY factsanddetails.com

INDONESIAN ELECTIONS IN 2004 AND 2009 factsanddetails.com

SUSILO BAMBANG YUDHOYONO (PRESIDENT OF INDONESIA 2004-2014): LIFE, CAREER, INTERESTS factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER YUDHOYONO (2004-2014) factsanddetails.com

2014 ELECTION IN INDONESIA: ROCK STARS, RALLIES AND SMEAR CAMPAIGNS factsanddetails.com

JOKO WIDODO: HIS LIFE. CAREER, FAMILY, INTERESTS AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

JOKO WIDODO AS PRESIDENT: HIS FOLKSY STYLE, ACHIEVEMENTS AND CRITICS factsanddetails.com

2024 ELECTIONS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

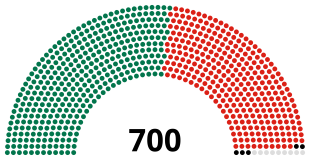

Results of the 1999 Elections in Indonesia

Abdurrahman Wahid: 373 votes (green)

Megawati Sukarnoputri: 313 votes (red)

Invalid votes: 5

Abstentions: 9

The main parties were the PDI-P of Megawati Sukarnoputri, Sukarno’s daughter; the National Awakening Party (PKB) of Muslim scholar Abdurrahman Wahid; and Golkar, Habibie's and Suharto's party; and the National Mandate Party (PAN) of Amien Rais; Megawati won 34 percent of the vote, a relatively disappointing showing. She had been expected to win 40 percent of the vote. In second was Golkar Party of with 22 percent of the vote. The National Awakening Party (PKB) of Wahid finished with only 11 percent of the vote. Twenty-one of the 48 parties that took part in the election managed to win seats in the House of Representatives.

Out of the 48 parties that contested the election, the largest 6 vote winners were the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI P) with 34 percent, GOLKAR with 22 percent, the National Awakening Party (PKB) with 13 percent, the Unity and Development Party (PPP) with 11 percent, the National Mandate Party (PAN) with 7 percent, and the Crescent and Star Party (PBB) with 2 percent of the vote. Several smaller parties won seats in the current Parliament (DPR), but, under law, will be required to merge in order to contest the next election in 2004. [Source: Cities of the World, Gale Group Inc., 2002, adapted from a 2001 U.S. State Department report]

According to Lonely Planet: Despite the ongoing instability, Indonesia’s June 1999 elections were largely a joyous celebration of democracy. years, Megawati Sukarnoputri was the popular choice for president, but her PDI-P (Indonesian Democratic Party for Struggle) could muster only a third of the vote. The Golkar party, without the benefit of a rigged electoral system, had its vote slashed from over 70 percent to just over 20 percent. [Source: Lonely Planet]

After Indonesia's 1999 Elections

In the 1999 national election, Megawati won the largest share of the popular vote. Parliament, however, resisted her elevation to the presidency. Opposition stemmed in part from conservative Muslim objections to a female head of state, and in part from maneuvering by Golkar, the former ruling party that had dominated Indonesian politics since 1965. When news of this political deadlock reached the streets, riots erupted in Jakarta. A compromise eventually emerged. Abdurrahman Wahid—widely known as Gus Dur—of the National Awakening Party became president, with Megawati installed as vice president. Although Wahid’s party was rooted in Muslim constituencies, he pursued an inclusive vision of Indonesian pluralism. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

After the June 1999 elections was a time of maneuvering and tough deal making between groups and parties on the road to the selection of the president by the parliament. Although Megawati received more votes, a coalition of other parties had the numbers to deny her the presidency. In October 1999 these parties united at the People’s Consultative Assembly and voted in Abdurrahman Wahid as the new president. Megawati was picked as vice president.

The June 1999 election not only chose members for the House of Representatives (DPR) it also selected members of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) and Provincial Legislative Council (DPRD). PDI-P won the majority seats in the DPR but it was up to the MPR to decide who would be Indonesia’s new president and vice president. The MPR elected Abdurrahman Wahid of PKB even though his party won 11 percent of the vote in the legislative election. The political atmosphere that followed the election was unstable and full of challenges, resulting in Wahid’s impeachment in July 2001, with Megawati taking over as president then.

Abdurrahman Wahid (President of Indonesia 1999-2001)

Abdurrahman Wahid was Indonesia's forth president and first to picked through popularly elected system (See above). He was a frail, nearly blind theologian who was head of Nahdlatul Ulama, the world's largest Muslim organization, with 35 million members in 1999. Despite being head of such a large Islamic organization he was known as an outspoken supporter of secularism and held a relatively liberal views and philosophies

Wahid was known as "Gus Dur." Gus is a Muslim honorific and Dur is an affectionate take on of the second syllable of his name. Wahid was viewed with some degree of perplexity by Indonesians. A common joke went: there are three things you can never be certain about: life death and Gus Dur. Some Indonesians believed that Wahid has magical powers. A taxi driver told the New York Times, "Gus Dur has a sixth sense and can send you bad luck." An Indonesian journalist said people often drank from his unfinished glasses of water in hopes of being blessed. Wahid was particularly revered in East Java, where many people considered him a living saint, with some saying they had personally seen Wahid perform miracles and appear in dreams and visions.

Wahid was known for his sharp mind and poor health, He was weakened by two strokes—one of which put him in a coma and was corrected by brain surgery. He also suffered from diabetes, high blood pressure, and circulatory problems. When he became president he was so blind he couldn't read his own prepared speeches and was guided every where by an aide, even around his home. Wahid relied on aides to brief him ,read documents to him and even describe the body languages of people around him. His aides guided him when he made his signature.

Tom Fawthrop wrote in The Guardian, Wahid “restored freedom and democratic rights to his country after 32 years of the Suharto dictatorship. A reformist Muslim scholar, in the world's most populous Muslim nation, Wahid was an important figure both among religious groups and political movements in espousing a liberal Islam and promoted inter-faith dialogue. As president of Indonesia from 1999 to 2001, he staunchly defended human rights, ethnic minorities and Indonesia's secular tradition. Few countries have enjoyed a more cultured man at the helm of state – a journalist, scholar and enlightened cleric, he took great delight in jazz and classical music and had a special passion for Beethoven. His wit was almost equal to his erudition. Upon losing the presidency in 2001, he quipped: "You don't realise that losing the presidency for me is nothing. I regret more the fact that I lost 27 recordings of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony." [Source: Tom Fawthrop, The Guardian, January 3, 2010]

Wahid Takes Power

In November 1999, Wahid became the president of Indonesia by outmaneuvering Megawati in voting in the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR). Before the voting Wahid was given little chance and Megawati was the odds on favorite. Wahid originally said he would support Megawati but changed his mind at the last minute when he saw an opportunity to win.

Megawati was figured to be shoo in for president. All she had to do was engage in a little horse trading and assemble a coalition of parties. In what many regard as unexplainable political ineptitude, she refused to do this and expected the parties to come to her and hand her the presidency on a platter. That didn’t happen. After Habibie withdrew his candidacy most of his supporters, who didn't like Megawati, decided to back Wahid along with Muslim conservatives, Wahid defeated Megawati by a vote of 373 to 313, with 5 abstentions,

Wahid became president even though his party only took 11 percent of the vote. One political analyst told the Washington Post, Megawati “lost it more than Gus Dur achieved it. She had it in front of her. If she had just taken the lead in trying to bring Amien Rais and Gus Dur with her, she would be president."

The defeat was a humiliation for Megawati, who was named vice president by Wahid. Although she was enormously popular among Indonesians, she had little experience in tough and tumble politics and making policy. After Wahid was selected, Megawati supporters rioted in Bali and set fire to the Jakarta Convention Center.

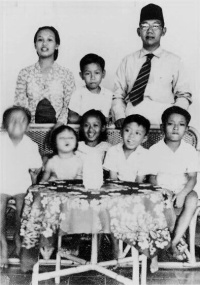

Wahid's Life

Wahid was born in the small town Jombang in East Java on August 4, 1940 into a family of scholars who established and ran Muslim schools. His father, Wahid Hasyim, was an independence hero in the struggle against the Dutch who was appointed religious affairs minister in 1949. His grandfather was a leading Muslim scholar and founder of Nahdlatul Ulama. Many members of his family were active in the national movement against the Dutch. Wahid was married in 1968. He fathered four daughters.

Wahid was educated at a Javanese Muslim school and had to repeat two years of high school because he often didn't bother to show up for class, preferring to spend his time in cinemas and libraries, and attended Islamic universities in Iraq and Egypt and flunked classes there too partly because he spent to much time reading about subjects as far ranging as French film and Jewish mysticism. He also studied briefly in Canada.

Wahid was officially a Muslim scholar. He could recite the entire Koran by heart. He taught at several Indonesian universities and Islamic boarding schools between 1972 and 1978. He was elected head of Nahdlatul Ulama, the world's largest Muslim organization, in 1984.

Tom Fawthrop wrote in The Guardian, “ Wahid studied at Al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt, from 1964 to 1966. Later he went to the school of literature at Baghdad University and graduated in 1970. Returning home, he joined the Institute of Research, Education and Information of Social and Economic Affairs, and became a journalist and social commentator. In 1984 he was elected chairman of the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), a conservative Muslim organisation which had been founded by his grandfather, Hasyim Ashari. His great influence on the nation sprang from his success in reforming the NU and his critical role in mobilising his people behind the "Reformasi" movement, eventually leading to the downfall of Suharto. [Source: Tom Fawthrop, The Guardian, January 3, 2010]

Wahid died in January 2010 at the age of 69 during surgery to remove a blood clot in his heart, At his funeral, Indonesian president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, praised him as the "father of multiculturalism and pluralism" who "raised awareness and institutionalised our respect for the diversity of ideas and identity, of religions, ethnicity and primordial ties". One of Wahid’s daughters, Zannuba Arifah Chafsoh (popularly known as Yenny Wahid), his longtime aide, is now the director of a thinktank devoted to his ideals, the Wahid Institute.

Wahid's Character

Wahid was known for his earthiness and lack of pretension. He loved soccer (he one wrote about it in the magazine Tempo) and enjoyed listening to Beethoven, Mozart, Jim Reeves and “Me and Bobby McGee” sung by Janis Joplin. His favorite food was sashimi.

Wahid preferred to speak extemporaneously without notes and people never knew what he would say. Although he was regarded as disorganized and often closed eyes when listening to people, he could recite every verse of the of the Koran and knew 2,000 phone numbers by heart.

Wahid was greatly revered as a brilliant scholar and cultured man. He advocated a tolerant and inclusive form of Islam and was supporter of human rights for minorities, women and non-Muslims. Wahid defended Salom Rushdie, spoke up in support of Israel, supported women's rights and met with Castro and Gaddafi. He once said: "I am not anti anyone."

Wahid was also known for his sense of humor, one-liners and pranks. He told dirty jokes to Clinton and posed beside a bust of Beethoven with a traditional Indonesian hat. He once said Christians are closer to God than Muslims because they whisper their prayers rather than blast them over loudspeakers. Shortly after taking office, Wahid said, "Now, as President, I'll have to wear shoes." On Habibie, Wahid said, he "doesn't have political sense, or a sense of politics." On Megawati, he said, "Although she is stupid, she loves people."

Wahid as President

Wahid promised to run a corrupt-free government and said he wanted the set up a federalist system in Indonesia. He was credited with promoting free speech and freedom of the press, reducing the role of the military in civilian government, opening up talks with separatist in Aceh and Irian Jaya and reducing corruption. He supported free market economics.

Wahid was the darling of many liberal Muslims and, particularly, Western Indonesia-watchers, many of whom knew him personally and saw him as an exponent of liberal democracy, pluralism, openness, and informality, the antithesis of everything they had despised about New Order government. To some degree, he was all those things. [Source: Library of Congress]

Wahid hoped to introduce a bicameral legislature, direct elections of the president, a system of judicial review, an American-style bill of rights and decentralization of power to the provinces. Wahid's first 35 appointees, included people from seven political parties, the fiver religious faiths and the military. He said on a number of occasions that his favorite move was “High Noon” and compared his high-stakes sacking of armed forced chief General Wiranto to the climatic showdown in the film

Tom Fawthrop wrote in The Guardian, “Wahid inherited a country with a struggling economy and many other problems. He revoked many of Suharto's repressive laws and ushered in an era of greater press freedom. He visited the Sumatran province of Aceh, negotiating with the Free Aceh Movement (GAM). He apologised for Indonesian atrocities in East Timor, supporting the United Nations' call for a trial of the military officers responsible. Defying military advice, he accepted the renaming of Irian Jaya to West Papua, demanded by the indigenous Free Papua Movement (OPM), losing him considerable public support. In his struggle to assert civilian control over the military, he successfully dismissed the powerful security minister, General Wiranto, cited by the UN as responsible for crimes against humanity committed in East Timor in 1999 under his command. Wahid achieved all this despite poor health. He was a colourful, oddly eccentric president, who was given to unpredictable cabinet reshuffles and alliances. [Source: Tom Fawthrop, The Guardian, January 3, 2010 ]

“Whatever his political failings, he had few equals in setting an example of courageous leadership based on moral principle. He lifted the Suharto regime's bans on all forms of Chinese culture and the ban on Marxism and Leninism. He also came to the defence of Salman Rushdie for his controversial 1988 novel The Satanic Verses. Dealing with certain perceptions of the Muslim religion, Wahid declared: "Democracy is not only not haram [forbidden] in Islam, but is a compulsory element of Islam. Upholding democracy is one of the principles of Islam." Countering his many critics, Wahid responded: "Those who say that I am not Islamic enough should reread their Qur'an. Islam is about inclusion, tolerance, and community." His legacy of a human rights-based Islam is critical to Indonesia and the world at a time of dire challenge from religious bigotry and narrow-minded fundamentalism.”

Wahid’s Failures

As a leader, Wahid was erratic and antagonistic. He often spoke off the cuff and voiced impulsive ideas—such as establishing relations with Israel and allowing Aceh to become independent—in way that angered people and left them bewildered. He picked fights with his both rivals and allies, confronting them rather than working with them in the legislature. He was also criticized for making too many overseas trips (30 in his first 10 months in office).

Wahid was often photographed falling asleep during speeches. Sometimes his own speeches were delivered by someone else. Aides sometimes nudged him and then gave him a stick of candy to suck on. During his swearing in ceremony, Wahid butted his head on the microphone and had the words of the oath whispered in his ear while he pretended to read from a text in a folder in his hands. After the oath he appeared to doze off before he rose again to give his acceptance speech.

Both Wahid and those around him proved managerially and politically inept, unable to satisfy a diverse following. Many conservative Muslims had expected him to further their agenda of an Islamic state, and were appalled by Wahid’s insistence on religious tolerance and visiting Israel. Wahid's administration was also racked by political scandals and charges of corruption. Wahid's younger brother and masseuse were involved in scandals. He fired economic aides and replaced them with cronies. According to Lonely Planet: “As head of Nahdatul Ulama (Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisation), Wahid already commanded widespread support. However, his moves to reform the government, address corruption and quell conflict in outlying provinces were continually hamstrung by those who opposed such reform. Wahid’s effort to bring Suharto to justice were hindered by a corrupt and timid judiciary, and claims that Suharto was too ill to stand trial. Not helped by his failing health, Wahid’s 21-month presidency may be seen as a time when the wheels of reform began to turn, but were too often punctured by the powerful few who were set to lose so much as a consequence.

Sectarian Violence and Regional Divisions Under Wahid

Wahid was criticized for not doing enough to end sectarian violence. According to Lonely Planet: Wahid’s effort to bring peace to such areas as Aceh, Irian Jaya (which he renamed Papua) and Maluku were not helped by an army that seemed to use the conflict as a justification of a continuation of their influence and political presence. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Wahid attempted to pursue negotiated settlements to regional conflicts and supported greater autonomy for areas such as Aceh and West Papua in an effort to keep them within the republic. These policies infuriated both the military and Golkar, who viewed them as concessions to separatism. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Early in his presidency, Wahid dismissed General Wiranto, who was accused of overseeing atrocities in East Timor, a move that alienated the military. Indonesia soon entered a period of severe instability. Civilian–military tensions intensified, communal violence between Muslims and Christians spread, and “ethnic cleansing” occurred in parts of Kalimantan, where Dayaks attacked Madurese transmigrants. On Ambon, a minor altercation between a Christian bus driver and a Muslim passenger ignited a full-scale sectarian conflict, accompanied by widespread arson. Gangs seized control in provincial cities such as Kupang, West Timor, and across much of Lombok. Many Indonesians believed that elements within Golkar and hard-line military factions deliberately fueled the unrest to undermine Wahid’s presidency. Reports circulated of boatloads of young men arriving in port cities to provoke violence, allegedly backed by Golkar figures and members of the Suharto family. [Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Military leaders were shocked to discover that he intended to follow through on plans to hold them accountable for violence the armed forces had sponsored in East Timor, and they joined with some Muslim politicians in bitter opposition to his effort to open the long-silenced trauma of 1965–66 to public scrutiny and reconciliation. *

Wahid’s Fall

Reuters reported: When Wahid “assumed the highest office in the world's fourth most populous country he struggled to deal with the broken economy and an unstable and fragmented political system in need of a strong leader and good manager. His style was often perceived as bumbling and chaotic, and any hope that his penchant for jokes, formidable intellect and political skills would help lead Indonesia through the transition from authoritarian rule to democracy quickly fell flat. [Source: Ed Davies and Telly Nathalia, Reuters, December 30, 2009]

In August 2000, Wahid gave an "accountability speech" in which he apologized for not doing enough to solve Indonesia's problems. In the speech, which was read by at top aide, he announced he would give up some power to Megawati, who would be put in charge of running the day to day affairs of the government. Later he back tracked and said he gave Megawati "only duties," not power.

By the end of 2000, lawmakers had become so fed up with Wahid’s disorganized way of governing they began threatening him with impeachment, using corruption scandals as an excuse to do so. In one case, two close aides of Wahid received $2 million as a pay off to pardon Suharto’s son Tommy. There were allegations that Wahid’s wife was given $500,000 by Tommy (Wahid refused to pardon Tommy). On top of this $4.1 million was removed from the government’s food-distribution agency by Wahid’s former masseur, who people claimed was acting on Wahid’s behalf. Wahid was also accused of failing to declare a $2 million “gift” from the Sultan of Brunei. On the impeachment efforts, Wahid said, “Go ahead, I’m not worried. I had never wanted to be president anyway.”

Wahid’s Ouster

Already in poor health—blind and weakened by strokes—Wahid was politically isolated. In July 2001, Wahid was dismissed by the national assembly in a unanimous vote of 591-0 (Wahid’s 100 or so supporters boycotted the session) for incompetence, abuse of power and corruption. The vote took place hours after Wahid issued an emergency decree for the immediate suspension of the national assembly, Indonesia’ parliament and main legislative body. The decree was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and provided the parliament with ammunition to throw him out of office.

The military played a key role in Wahid’s ouster by not acting on his emergency decree. Tanks gathered around the presidential palace but they had their guns pointed at it rather away from it. At one point Wahid summoned the military chiefs to his office and threatened to fire them if they didn’t act on his decree. Instead the generals tried to persuade Wahid to resign. It appeared as if the military had the intent on ousting Wahid for some time, seemingly with the knowledge and approval of Megawati. In any case Wahid's impeachment in July 2001 paved the way for Megawati to assume the presidency.[Source: “Culture and Customs of Indonesia” by Jill Forshee, Greenwood Press, 2006]

Wahid responded to the impeachment vote by asserting it vote was illegal. A spokesman said the emergency decree he issued was “a jihad to save the state.” For a while Wahid holed himself up in the presidential palace and refused to leave. There was some discussion about turning off the electricity and water to get him to leave. Finally he left. His excuse: to go to the United States for medical treatment. As he departed, he was asked about the kind of government that would follow him. “I don’t know. I don’t care,” he said.

Wahid’s departure ended an effort to oust him that had been going on for more than a year and was characterized by moves by legislators to get him removed followed by protests by Wahid supporters. Before one legislative session was expected to call for his impeachment, thousand of Indonesian suicide warriors poured into to Jakarta to, they said, defend Wahid. Wahid supporters attacked a provincial parliament in Surabaya, burned churches and threw firebombs at police in the east Javanese town of Pasuruan. At one point a mob of 4,000 supporters broke into the Parliament compound in Jakarta, chanting “Long Live, Gus Dur!” and threatened to kill lawmakers that supported impeachment. Protesters calling for Wahid's resignation had their tongues cut with a rusty sword.

Some analysts believe that the way Wahid was removed set a bad precedent for democracy in Indonesia. They believe he should have been removed by following the impeachment procedure outlined in the constitution. Many of those who backed Wahid’s ouster were the same ones who helped him take the presidency months before. The impeachment was reportedly engineered by powerful Suharto supporters.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, , Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025