OUSTER OF SUHARTO

Coinciding with Suharto health and family problems in the late 1990s were demands by students and the middle class for more participation in the government. Before the Asian economic crisis in 1997-98 things were beginning to unravel for Suharto. The economic crisis created an atmosphere in which the process could unfold and be carried to fruition. One Western diplomat told National Geographic that he regarded the upheaval in Indonesia in the late 1990s as an “extraordinary trauma and a clashing of mental tectonic plates.” “Reformasi” was the name of the democratic reform movement that ultimately ousted Suharto.

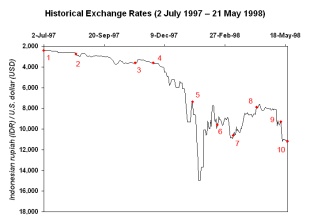

In 1997-98 Indonesia confronted economic collapse in the wake of a wider Asian financial crisis. The government’s response was slow and inadequate, pleasing neither liberals nor nationalist conservatives. Over an eight-month period, the value of the rupiah fell 70 percent. Over the course of a year, the economy as a whole shrank nearly 14 percent, 40 percent of the nation’s businesses went bankrupt, per capita income fell an estimated 40 percent, and the number of people living in poverty catapulted, by some accounts, to as much as 40 percent of the population. [Source: Library of Congress *]

By March 1998, when Suharto and his chosen running mate, Habibie, became president and vice president, respectively, it was clear that a line had been crossed. Public calls for reform turned angry, and within weeks bitterly antigovernment, anti-Suharto student demonstrations spilled out of campuses across the nation. On May 12, at Trisakti University in Jakarta, members of the police force, then under ABRI command, fired on demonstrating students, killing four (and two bystanders) and wounding at least 20 others. This event, which created instant martyrs and removed any lingering hesitancy for a broad spectrum of Indonesians, launched several days of horrific violence, which ABRI could not or would not control. In Indonesia as a whole, an estimated 2,400 people are said to have died; as much as US$1 billion in property was damaged; and tens of thousands of foreign residents and Indonesian Chinese fled the country. *

Pressured by the nationwide protests, Suharto resigned in May 1998, having finally lost the confidence of even his closest associates and military clique. The government that had come to power promising stability and economic growth now demonstrably could deliver neither, and its leader was precipitously abandoned. In a simple ceremony held on May 21 at 9:00 a.m., Suharto resigned, bringing a symbolic end to the now jaded and discredited New Order leadership. John Gittings wrote in The Guardian, “After a year's silence, the former president emerged to deny claims he had amassed a fortune, filing a suit against Time magazine for publishing detailed allegations. There were suggestions he had threatened to implicate other members of the Jakarta elite if the investigation proved too vigorous.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

SUHARTO: HIS LIFE, PERSONALITY AND RISE TO POWER factsanddetails.com

INDONESIA UNDER SUHARTO: NEW ORDER, DEVELOPMENT, FOREIGN POLICY factsanddetails.com

REPRESSION UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

VIOLENT CRACKDOWN ON COMMUNISTS IN INDONESIA IN 1965-66: KILLERS, VICTIMS, REASONS factsanddetails.com

CORRUPTION AND FAMILY WEALTH UNDER SUHARTO factsanddetails.com

1997-98 ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

SUHARTO AFTER HIS RESIGNATION: TRIALS, DEATH, LEGACY, VIEWS, FAMILY factsanddetails.com

Decline of Suharto’s New Order

The New Order probably reached the peak of its powers in the mid- to late 1980s. The clear success of its agricultural strategy, achieving self-sufficiency in rice in 1985, and its policies in such difficult fields as family planning—Indonesia’s birthrate dropped exceptionally rapidly from 5.5 percent to 3.3 percent annually between 1967 and 1987—earned it international admiration. Economic progress for the middle and lower classes had seemed to balance any domestic discontent. In retrospect, however, signs of serious weakness were discernible by about the same time. Although there had always been a certain level of public and private dissension under New Order rule, by the early 1990s it had grown stronger, and the government appeared increasingly unable to finesse this opposition with force (veiled or otherwise) or cooptation. In addition, intense international disapproval, particularly over East Timor, proved increasingly difficult to deflect. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Several important shifts had taken place, which in turn altered the New Order in fundamental ways. One was international: the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the end of the Cold War both provided New Order leaders with frightening examples of political upheaval and religious and ethnic conflict following in the wake of a relaxation of centralized power, and these events also left Indonesia more vulnerable to pressures from the West. An important result was a new uncertainty in domestic policy, for example, toward public criticism, Islam, and ethnic and religious conflict. In the military, opinions grew more varied, many of them frankly disapproving of certain government policies, including those toward the armed services. A second important change took place as the advice of “technocrats” responsible for the successfully cautious economic strategizing of the 1970s and 1980s began to give way to that of “technicians” such as Suharto protégé Bacharuddin J. (B. J.) Habibie (born 1936), who became a technology czar favoring huge, risky expenditures in high-technology research and production, for example by attempting to construct an indigenous aeronautics industry. *

Some observers detected a third area of change in the attitude of Suharto himself. He grew more fearful of opposition and less tolerant of criticism, careless in regard to the multiplying financial excesses of associates and his own children, and increasingly insensitive to pressures to arrange a peaceful transition of power to new leadership. And, by the late 1990s, he seemed to lose the sense of propriety he had professed earlier. Circumventing all normal procedures, Suharto had himself appointed a five- star general, a rank previously accorded only the great revolutionary leader Sudirman (1916–50) and his successor, Nasution. Further, he not only ignored his own earlier advice against running for a seventh term but also placed daughter Tutut, son-in-law General Prabowo Subianto (born 1952, and married at the time to Suharto’s second daughter, Siti Hediati Hariyadi—known as Titiek, born 1959), and a host of individuals close to the family in important civilian and military positions. These and other transgressions lost Suharto and many of those around him the trust of even his most loyal supporters, civilian as well as military. *

The changes of greatest long-term significance, however, may have been social and cultural. New Order architects had planned on controlling the nation’s politics and transforming its economy, but they had given comparatively little consideration to how, if they succeeded, society—their own generation’s and their children’s—might change as a result. If economic improvement expanded the middle classes and produced an improved standard of living, for example, would these Indonesians begin to acquire new outlooks and expectations, new values? What might be the cultural results of much greater openness to the outside, especially the Western, world?

Although the New Order became infamous for efforts to inculcate a conservative, nationalist Pancasila social ideology, and to promote a homogenized, vaguely national culture, these endeavors were far from successful. Despite a penchant for banning the works of those considered to be influenced by communism (author Pramudya Ananta Tur became the world-famous example) and an undisguised distaste for “low,” popular culture (a high government official once disparaged dangdut, a new and wildly popular music style blending modern Western, Indian, Islamic, and indigenous influences, as “dog-shit” music), the New Order’s leaders turned a comparatively blind eye to cultural developments and seemingly had little idea what such changes might reflect of shifting social values. *

Indonesianist Barbara Hatley has pointed to “a vigorous process of reinterpretation” of tradition during the New Order period, as well as new reflections of the present. For example, in a series of four novels about the lives of young, urban, middle-class Indonesians in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Yudhistira Ardhi Nugraha (born 1954) satirized the world of their pompous, hypocritical parents, civilian as well as military. Playwright Nobertus “Nano” Riantiarno (born 1949) used mocking language and absurdist humor to make fun of the world of politicians and government bureaucrats in his 1985 Cockroach Opera, which was finally banned five years later. By the late 1980s, many of the older generation had begun to question the implicit bargain they had struck with the New Order; their children, who had little or no memory of the Sukarno period or the dark days of the mid-1960s, merely saw the limitations and injustices around them and resisted, often with humor and cynicism. *

Suharto's Decline

In April 1996,Suharto's wife, of 49 years, Raden Ayu Siti Hartinah, widely known as Ibu Tien, died suddenly while Suharto was sportsfishing. There were rumors that she died trying to break up a gun fight between two of her children. Suharto was greatly distressed. Two months later Suharto flew to Germany for treatment for kidney and heart problems. Tien reportedly wanted Suharto to resign while the going was still good but according to some insiders he hung for the sake of his children, so their businesses would survive.

Reporting from Ibu Tien’s funeral Susan Berfield and Keith Loveard wrote in Asiaweek:” President Suharto sat cross-legged on the floor beside the body of his wife, Siti Hartinah. His head was bowed, his face ashen; he seemed almost unaware of the mourners who filed through his home on April 28, briefly pressing his hands as they passed. Ibu [mother] Tien, as the 72-year-old first lady was known, had died suddenly in the early morning of a heart attack thought to have been brought on by diabetes. She had been rushed to a nearby army hospital after she complained of breathing difficulties, but doctors could not save her.” [Source: Susan Berfield and Keith Loveard, Asiaweek, April 1996]

“Tien had been a quiet but powerful force in building the family's political and economic empire after Suharto assumed power in 1966. She was the president's closest confidant. And, in his first days without her, he seemed distraught. For some time now, people have been asking how much longer Suharto will rule, and who will succeed him. The first lady's death has naturally intensified the speculation about the 74-year-old president's plans. “

After his wife's death, Suharto rose before dawn to recite Muslim prayers and gained weight from overeating. He also suffered from phlebitis, kidney ailments and depression and was unable to exert much control over the greed of his children. Insiders said Suharto was surrounded by ministers he didn't trust and yes men who didn't watch his back or keep an antenna up for public sentiments.

Openness Campaign, Megawati and Anti-Suharto Riots in the Mid-1990s

Although its total share of votes declined, Golkar won the 1992 elections, securing 282 of the 400 elective seats. In March 1993, Suharto was elected to a sixth term as president. Otherwise, the early 1990s was turbulent time. In December 1992, the island of Flores suffered Indonesia’s worst earthquake in modern times. The quake killed up to 2,500 people and destroyed 18,000 homes. Suharto cronies were accused of siphoning disaster-relief funds. A major scandal occurred in March 1993 with the sale of $5 million in fake shares on the Jakarta Stock Exchange. Violent labor unrest broke out in Medan in April 1994, and ethnic Chinese became the target of such violence. Many incidents of rural unrest continued in 1995 and 1996 in East Timor and in Kalimantan. [Source: Junior Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

In 1995, Suharto launched a limited “openness campaign” that relaxed press controls, released some political prisoners, reduced military involvement in civilian affairs, and expanded social programs. High-profile detainees held since 1965 were freed, and about 1.4 million former political prisoners had their civil rights restored. However, the reforms proved short-lived: the campaign effectively ended when the government shut down three critical news magazines. [Source: John Gittings, The Guardian, January 27, 2008]

Despite the reversal, political tensions grew. Economic inequality widened, grassroots dissatisfaction increased, and opposition parties—especially the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI)—gained popularity. In 1996, the government engineered a split within the PDI, removing its popular leader Megawati Sukarnoputri, Sukarno’s daughter. This move sparked riots in Jakarta, leaving several people dead and many injured, and turned Megawati into a national symbol of resistance to Suharto’s rule.

The run-up to elections in May 1997 was an unusually violent one, dubbed the "festival of democracy," as voters and demonstrators brought rocks, bricks, knives, machetes, and even snakes to the campaign. There was a ban on parades of trucks, cars, and motorcycles. The violent suppression of Megawati’s supporters, involving hired thugs, riot police, and army troops, exposed the limits of political reform under the New Order. Although Suharto briefly hinted at retirement, the regime ultimately reaffirmed his leadership, setting the stage for the larger unrest that would culminate in his downfall two years later. Describing the riots in Jakarta, Ron Moreau wrote in Time, "The first wave of attacks came from about 100 young thugs, bused in for the job by the Indonesian government. Early Saturday morning, they began hurling rocks at supporters of Megawati...Then members of a rival faction opposed to Megawati joined in, followed by the heavy assault team: hundred of riot police, and soldiers in green camouflage." Armed with rattan canes, wooden truncheons and electric cattle prods, they stormed PDI headquarters. After breaking through the iron gate, they set upon about 150 Megawati supporters inside the courtyard, beating them with sticks."

Suharto and the 1997- 98 Asian Financial Crisis

Marilyn Berger wrote in the New York Times: The Asian economic turmoil in 1997 exposed Indonesia’s economy as on the brink of collapse. The currency lost 30 percent of its value in 1996, a drought made rice scarce, unemployment rose and the widening income gap led to rioting and violence. Mr. Suharto turned to the International Monetary Fund, which agreed to a $43 billion bailout if Indonesia would abide by its terms. His signing of those terms was seen as a humiliating capitulation, but he equivocated when it came to instituting them. Many saw his hesitation as an effort to protect the fortunes of his family and friends, money widely believed to have been stashed in foreign banks.[Source: Marilyn Berger, New York Times, January 28, 2008]

“Mr. Suharto called for belt-tightening. He raised fuel prices, then revoked the order. He promised bank reform and ended tax breaks, then reversed himself or left wide loopholes. His failure to come to grips with economic problems brought a wave of student unrest. In May 1998, student rallies spilled from the campuses into the streets and across the archipelago. Hundreds died in fires and clashes with security forces.

“Apparently unable to grasp the seriousness of the situation, Mr. Suharto left on a trip to Cairo, but was forced to cut it short in an effort to restore order. The economic crisis was a challenge that he did not seem to know how to handle. “This is something he cannot shoot, he cannot put in jail, he cannot close down, like our newspaper,” said Jusuf Wanandi, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Jakarta, an Indonesian policy institute.

See Separate Article: 1997-98 ASIAN FINANCIAL CRISIS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Riots Against Suharto in 1998

The 1997 Asian financial crisis devastated Indonesia, triggering economic collapse as the rupiah plunged, banks failed, businesses closed, and millions lost their jobs. An IMF rescue package offered financial support in exchange for sweeping reforms, including ending food and fuel subsidies, dismantling monopolies, and abandoning state-backed projects tied to Suharto’s family. Rising prices and unemployment fueled unrest, with ethnic Chinese businesses—long prominent in commerce—often scapegoated during sporadic riots. In a single year, the number of Indonesians living in poverty surged from about 20 million to nearly 100 million. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Although Suharto was reelected in early 1998, opposition from students, Islamic groups, and reform advocates intensified. As IMF-mandated fuel and electricity price hikes took effect, demonstrations spread from university campuses into the streets. In April and early May 1998, riots erupted across major cities, targeting symbols of cronyism, including businesses linked to Suharto and his family.

The turning point came on May 12, 1998, when security forces shot and killed four students at a peaceful protest at Trisakti University in Jakarta while Suharto was abroad. According to some reports soldiers initially used rubber bullets and switched to live ammunition before the four students were shot dead. A Western diplomat told the Washington Post, "It was not a sudden burst of fire. It was a slow deliberate fire, for over an hour, and that can be proven...You're talking about targeting—that counts for the high number of kills for the number of wounded." One student, 21-year-old Henry Hartanto was killed by a bullet in the back when he paused briefly to wash tear gas from his face with water from a plastic bottle. Another student, 20-year-old Hneriawan, was shot through the back and the neck and sat down and died by the university flag pole. A third student, 21-year-old Hafidhin Royan wasn't even involved in the protests. He came to the university that day to finish assignments for an engineering class before heading home for summer break. He was shot in the head above the ear.

On May 13, funerals were held for the students that had been shot. Afterward thousands of protestors poured out of Jakarta's slums and converged on the commercial district: rioting, looting department stores and supermarkets and attacking banks, business and enterprises associated with Suharto, his families and his cronies. Also hard hit were the Chinese, whose businesses were looted and destroyed. Students set up barricades and lit fires on hijacked trucks. Soldiers rappeled from helicopters but were outnumbered. Mobs ruled the streets of Jakarta and began venting their anger at the Chinese. There were disturbing accounts of rape and murder. In one instance 15 Chinese were burned alive in a torched night club because they were afraid to go outside. In another case Chinese girls were gang raped in front of their mother by men with military style haircuts.

In the three days of rioting that following the shooting deaths of the students, 2,000 cars, trucks and motorcycles were destroyed and $1 billion in damages was caused in Jakarta alone. Over 500 bank branches were attacked and 30 of 50 Hero supermarkets were looted while other food chains closed down. On May 15, than 200 people were burned death in a shopping mall in Borneo that was attacked and set on fire by rioters. Most of the dead were looters. Dozens of others died in three other shopping mall fires. Despite threats of further repression, anti-Suharto protests intensified nationwide. With public anger mounting and even members of his own cabinet urging him to step down, Suharto’s grip on power collapsed, setting the stage for his resignation days later.

See Anti-Chinese Riots Under VIOLENCE TOWARDS CHINESE IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Events Before Suharto Resigns

On May 15, when the riots spiraled out of control, Suharto returned home from Cairo, where he had told Indonesians that "it would not be a problem" if he would become a “pandito”, or sage. This was viewed as signal that he was willing to resign. Among the first things he did after returning to Indonesia was make the "difficult decision" to raise the prices of gasoline, electricity and bus and train tickets by around 70 percent to make the IMF happy. He also threatened to impose martial law if the chaos continued. On May 16, Suharto tried reshuffling his cabinets, but none of the people he asked to take the new positions was willing to serve. He thought about imposing martial law but generals made it clear they wouldn't carry it out. Even his fortunetellers told him it was time to go.

On May 18, students were allowed into the Parliament building by the government in an effort to placate them. The students took over the building. They also gathered outside, creating a carnival atmospheres with people climbing on the roof and unfurling banners calling for Suharto to resign and makeshift musicians banging out rhythms on bottles and cans. Students created a wooden effigy of Suharto with a dollar bill pasted across his eyes. A sign above his head said "material President".

Describing the scene on May 19, Mark Landler wrote in the New York Times, "Hundreds of student protesters barged into the main chamber of the House of Representatives, filling up seats and galleries and conducting a sort of spontaneous shadow government. One young man took the podium to offer a dead-pan impersonation of Gen. Wiranto, the Defense Minister....Soldiers did not venture into the sprawling complex, which gave the students free rein and turned Parliament into an Indonesian version of Fort Lauderdale Fla. during spring break.”

Parliament Demands Suharto's Resignation

On May 18, while the students occupied the Parliament building, Assembly Speaker Harmonoko, who had before been known as a Suharto loyalist, announced that he and other parliament members no longer supported him and called for Suharto "to step down, for the sake of unity and integrity of the nation." Suharto refused. At this point he still had the support of the military.

Seth Mydans wrote in the New York Times, "It was an extraordinary moment. The obedient legislature that Mr. Suharto had created expressly to give legitimacy to his one-man rule— a parliament that never questioned his orders—turned the Machinery of government against him." A Western diplomat told the New York Times, "They have trapped him. Everything Suharto has ever done, he has done by the letter of the Constitution. He mentions the Constitution in almost every speech. Now his only option is to go outside the Constitution.

On May 20, Harmoko and other parliamentary leaders again called for Suharto to reign. Suharto again refused. He announced he would hold new elections and not run for president. He then reached out to intellectuals for support but was rejected by almost everyone he asked. At this juncture, Suharto had been abandoned by hand-picked legislature and moderate intellectuals. Now even his close fiends and vice president had reportedly had enough and the only thing propping him up was the military when Harmoko gave Suharto an ultimum: resign or face a special parliamentary session that demand his ouster.

Military Withdraws Its Support of Suharto

On May 21, Vice President Habibie gave Suharto a letter of resignation signed by half of his cabinet. Although several prominent Indonesians had come to Suharto's home pleading with him to resign Suharto refused to do so. In the evening, Gen. Wiranto, who Suharto had appointed as Defense Minister only a few months before, met with Suharto and told him the military could no longer support him. The two men discussed Suharto's option. Suharto finally gave in and said that he would resign if he was given assurances that his family and wealth would be protected.

In the end it was the military that made the decision that Suharto was through. They set up a military committee to study reforms that announced that real elections should be held in the year 2000 and that Suharto and his family should turn their wealth over to the state. High-ranking generals in the military were the ones that gave the okay for students to to be let into Parliament. Marzuki Darusman, a human rights activist told Newsweek, the generals "decided to allow the students to keep the pressure on Suharto in the public protests and to activate a constitutional and legislative process that would remove him from office."

Suharto Resigns

Suharto resigned on May, 21, 1998. He called important aides and generals to his house and went before the nation on television with his hands visibly shaking and announced his resignation in a short prepared speech. Suharto said, "I have decided to hereby declare that I withdraw from my position as the president of the Republic of Indonesia...I'll say thank you very much for your support and I am sorry for my mistakes and shortcomings. I hope the Indonesian country will live forever." Upon the announcement, students occupying the Parliament building let out whoops of joy, danced in the fountains and partied for three days while soldiers played cards in the shade.

The Jakarta Post reported: “Time stood still for a moment on the morning of May 21, 1998. Millions of hearts skipped a beat upon hearing the announcement on television. President Soeharto was stepping down from power. Disbelief was followed by amazement as pictures appeared of a hastily conducted ceremony at Merdeka Palace. A tired-looking Soeharto stepped aside in favor of a tense-looking B.J. Habibie. Many felt the fall was coming, but one is never prepared for such an historical moment. [Source: Jakarta Post, May 23, 2005]

Many ordinary Javanese believed that end for Suharto began when his wife died. As greedy as some accused her of being was she was able to keep the Suharto clan under tight reins. After her death, the greed of Suharto's children and cronies seemed boundless and Suharto did little to reign them in. Suharto's position was still secure until the Asian Financial Crisis occurred, when Suharto failed to hold up his end of the bargain by provided economic growth and stability in return for support for his unquestioned power.

In the end it was ironic that a military man like Suharto who spent much of his career battling Communism was toppled by forces unleashed by capitalism. After the economy went into a tailspin, it wasn't too late for Suharto if he had show leadership and willingness to implement reforms. Instead he came off as out of touch and his staunchest supporters in the government and military decided he had to go.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025